Introduction

Few birds in North America are as widespread and widely reviled as the House Sparrow. Intentionally introduced to the U.S. starting in 1850, the species quickly spread across the continent (Robbins 1973). It was first recorded in Virginia in Prince William County in 1887 (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007) and was soon considered an abundant pest known for displacing or killing native species (Bailey 1913). Today, many organizations advise caretakers of nesting sites for Eastern Bluebirds (Sialia sialis) and Purple Martins (Progne subis) on how to control House Sparrow competition at nest boxes.

Nonetheless, the House Sparrow is an easily accessible bird in highly urbanized areas, where observation of its squabbling flocks and downspout nests can still spark a lifelong love of birdwatching.

Breeding Distribution

House Sparrows occur statewide but are largely restricted to urban and agricultural areas (Figure 1). Accordingly, the likelihood of House Sparrow occurrence is dramatically higher in blocks with a higher proportion of agricultural and developed land cover. They are virtually guaranteed to occur in any block that was more than 20% urban cover, while they are less likely to occur in blocks with numerous different habitat types or a higher proportion of shrubland and grassland habitats. They are also largely absent from intact forests as their likelihood of occurring in blocks with a higher proportion of forest cover and larger forest patches is low.

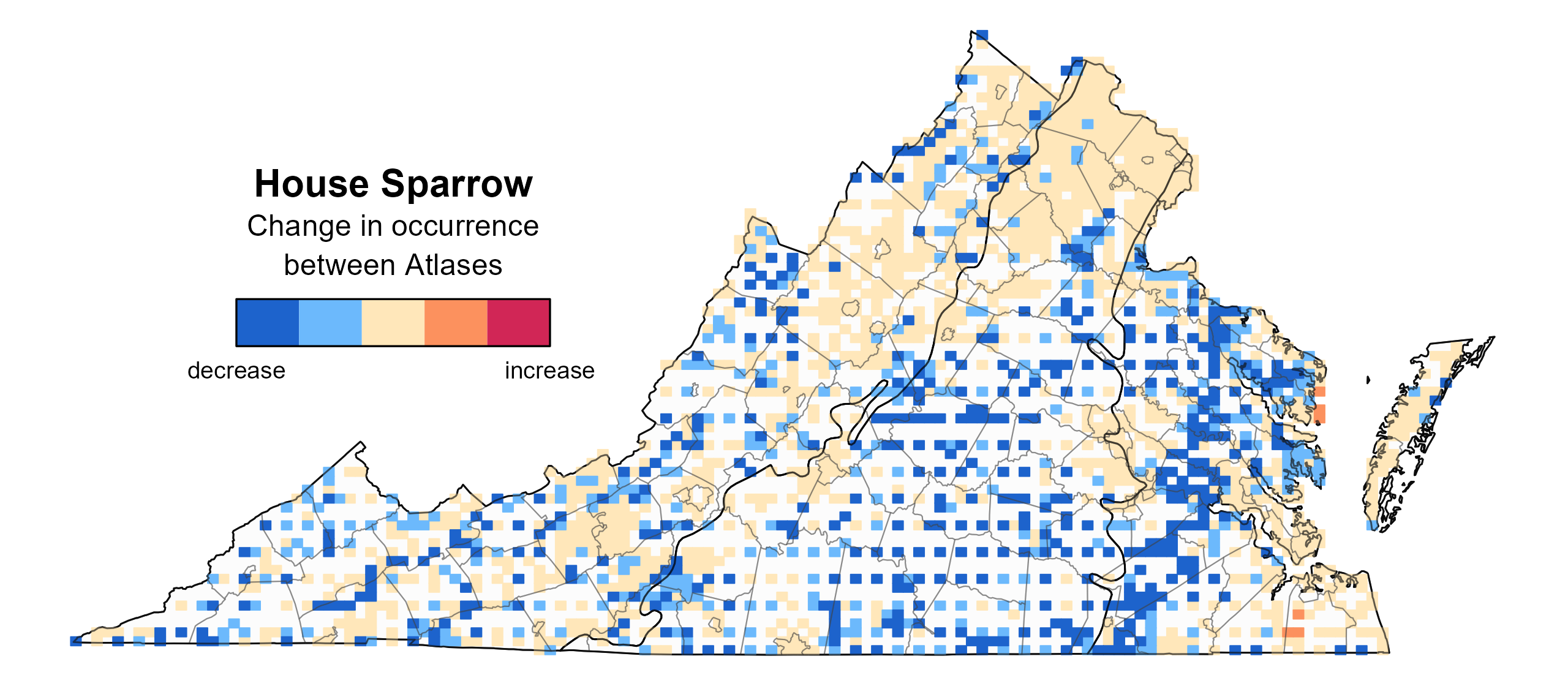

House Sparrow’s likelihood of occurrence remained constant in urban areas between the two Atlas periods; however, throughout the remainder of the state, it was much less likely to occur (Figures 1 to 3). This change can be attributed to widespread population declines in the species (see Population Status).

Figure 1: House Sparrow breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

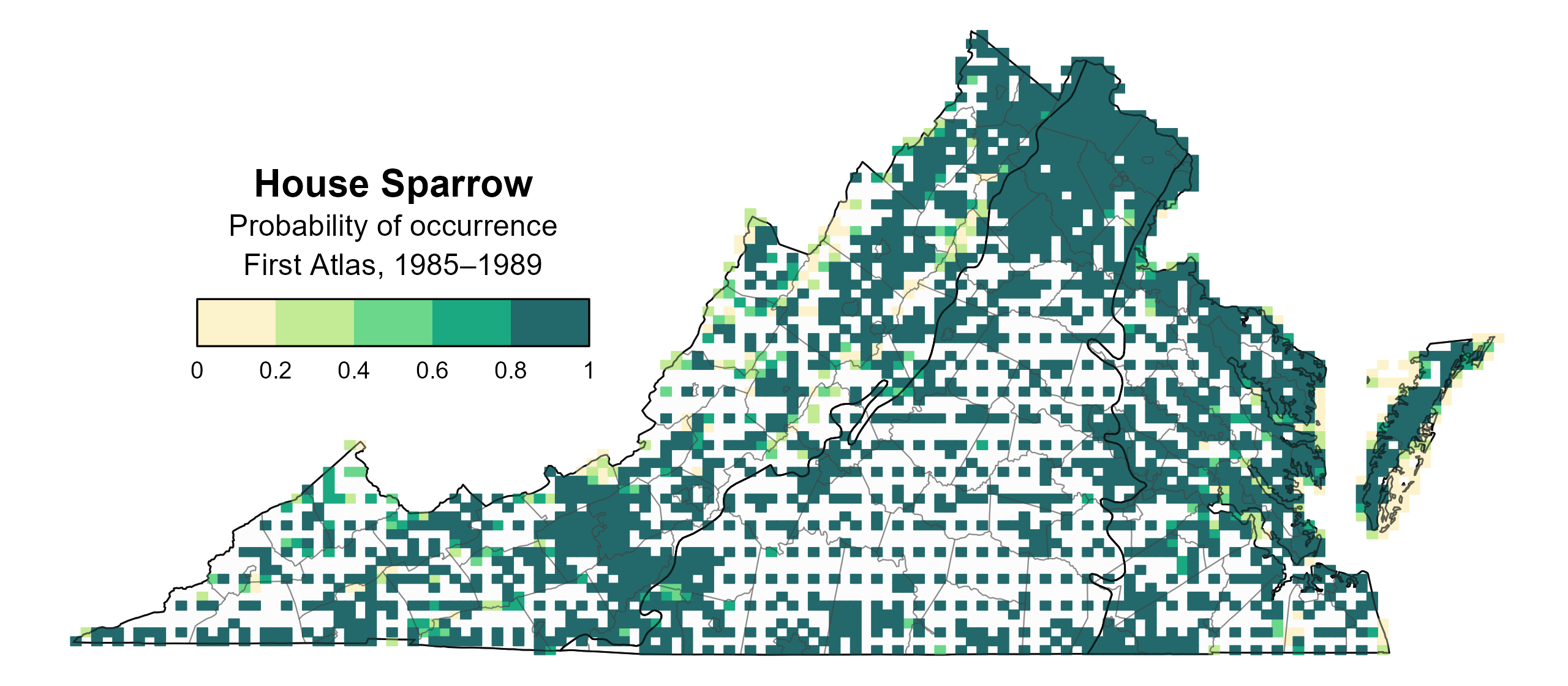

Figure 2: House Sparrow breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: House Sparrow change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

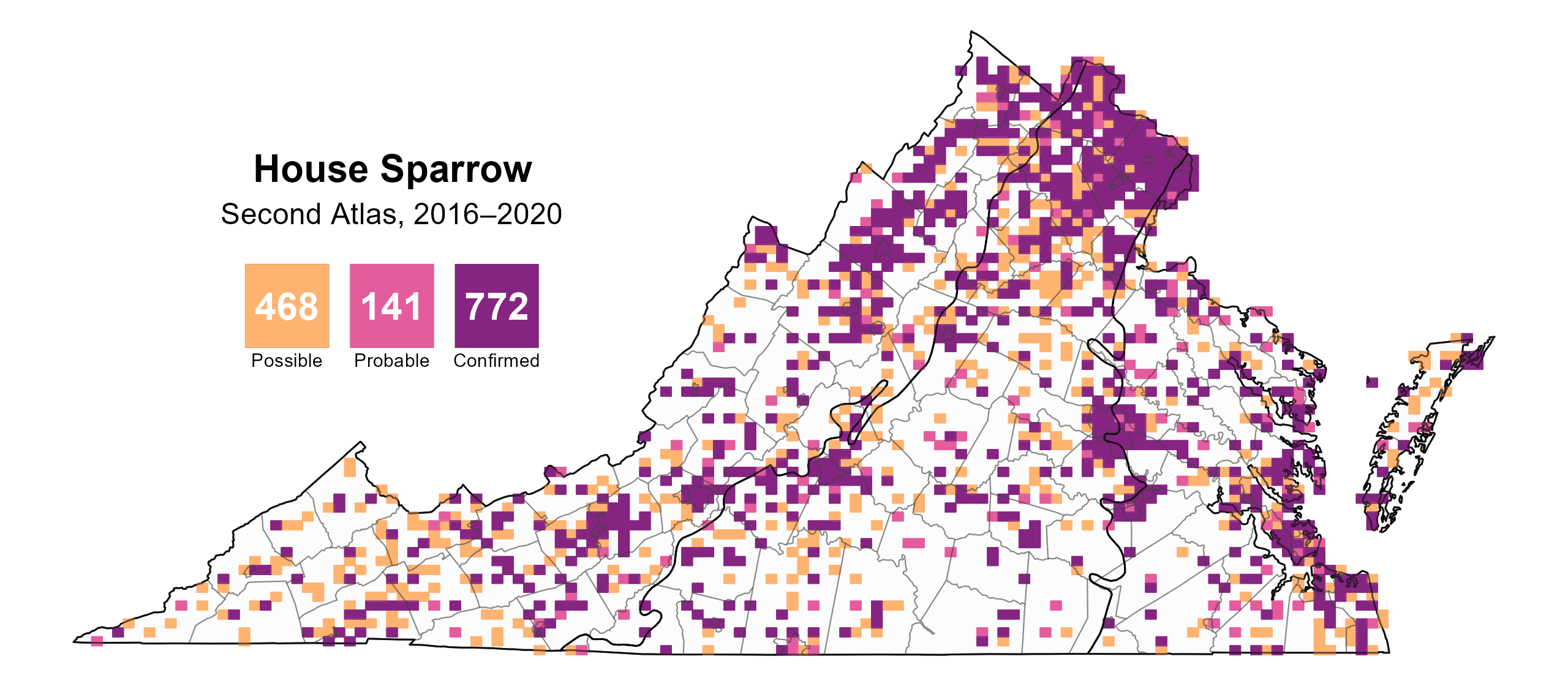

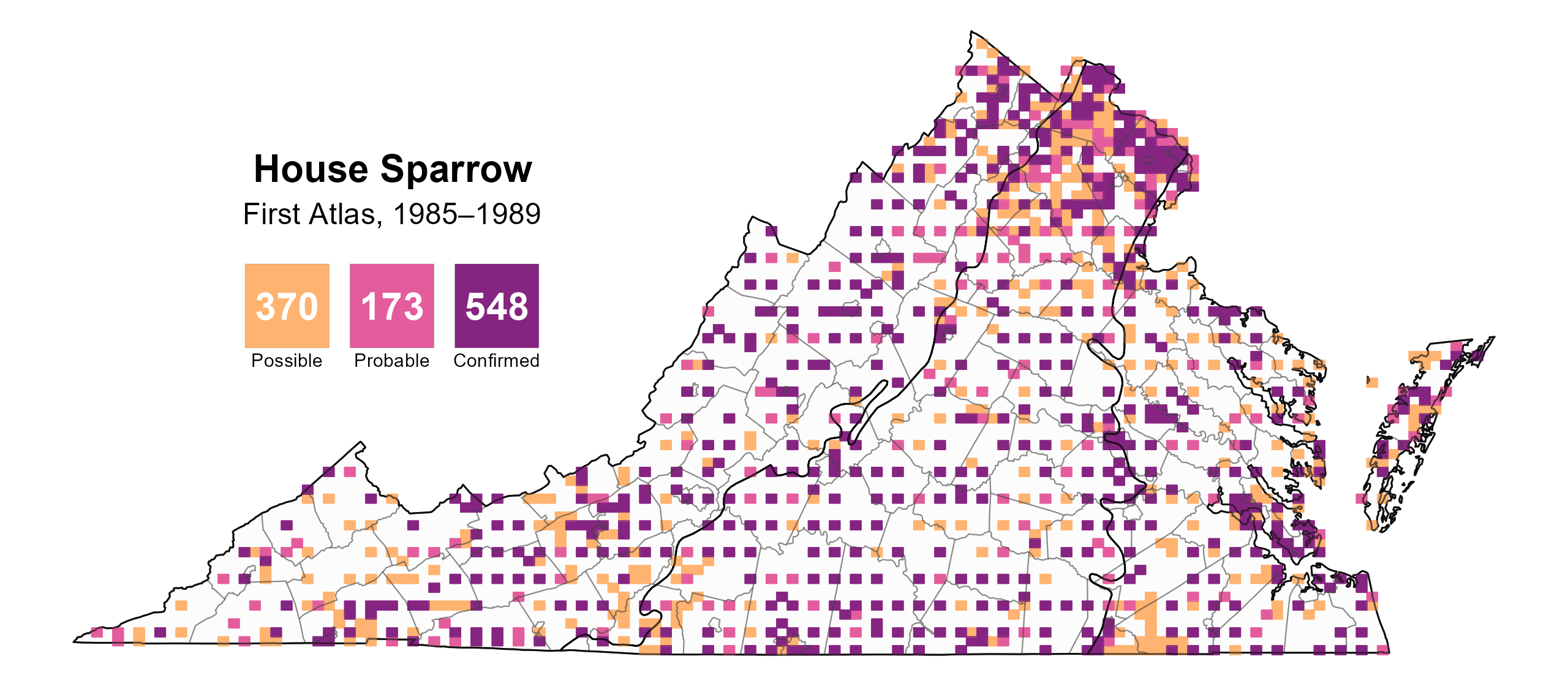

House Sparrows were confirmed breeders in 772 blocks and 128 counties and probable or confirmed breeders in 132 out of 133 counties in the state (Figure 4). The only exception was the city of Lexington, where it was classified as probable just outside city limits but only possible in the city. This is very likely due to lack of survey effort, and it can be safely assumed that House Sparrows breed in every county and city where they occur. House Sparrows were observed breeding across the entire state during First Atlas as well (Figure 5).

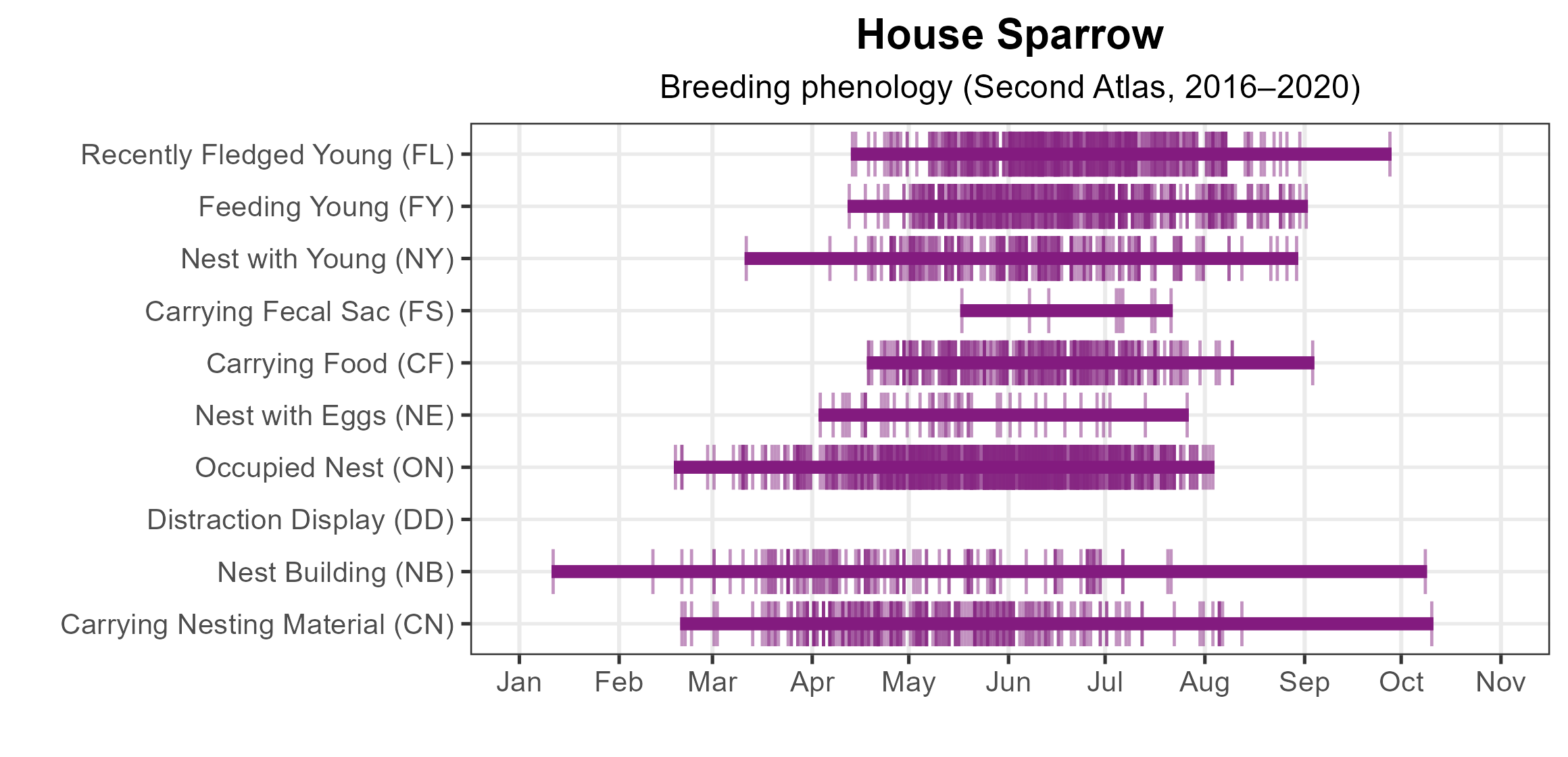

Breeding was confirmed from February 18 (occupied nest) through September 27 (recently fledged young), with eggs observed from April 3 to July 26 (Figure 6). One exceptionally early House Sparrow was observed nest building on January 11. Previous breeding records span from April 1 (eggs) through August 24 (recently fledged young) (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). The exceptional duration of breeding activity can be attributed to House Sparrow’s capacity for multi-brooding: they can produce up to three or four broods in a year (Lowther and Clink 2020).

For more general information on the breeding habits of the House Sparrow, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: House Sparrow breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: House Sparrow breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: House Sparrow phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

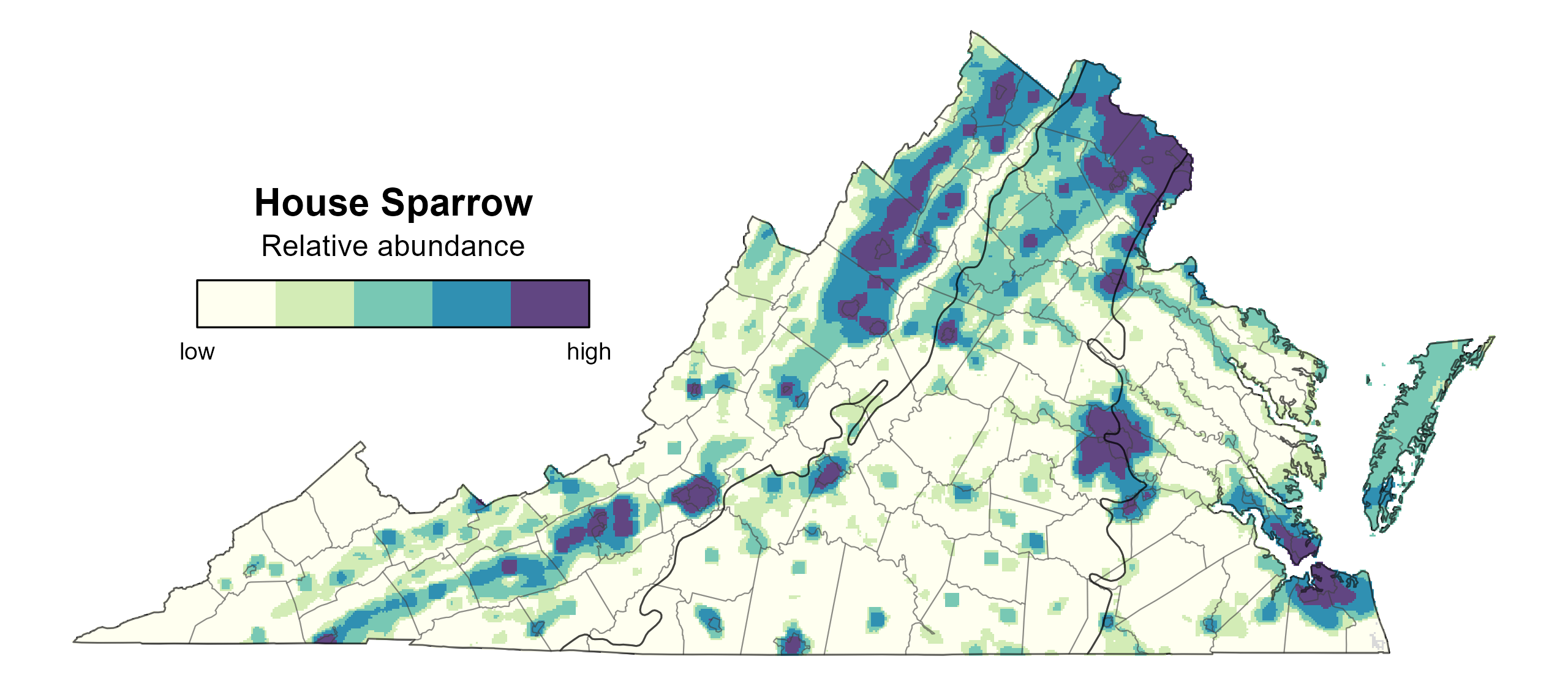

The relative abundance of House Sparrows was estimated to be highest in areas surrounding major cities: Richmond, Hampton Roads, Roanoke, Winchester, and much of Northern Virginia (Figure 7). Abundance was lowest in the Cumberland Mountains and along the Blue Ridge Mountains, both of which are high-elevation and primarily forested landscapes.

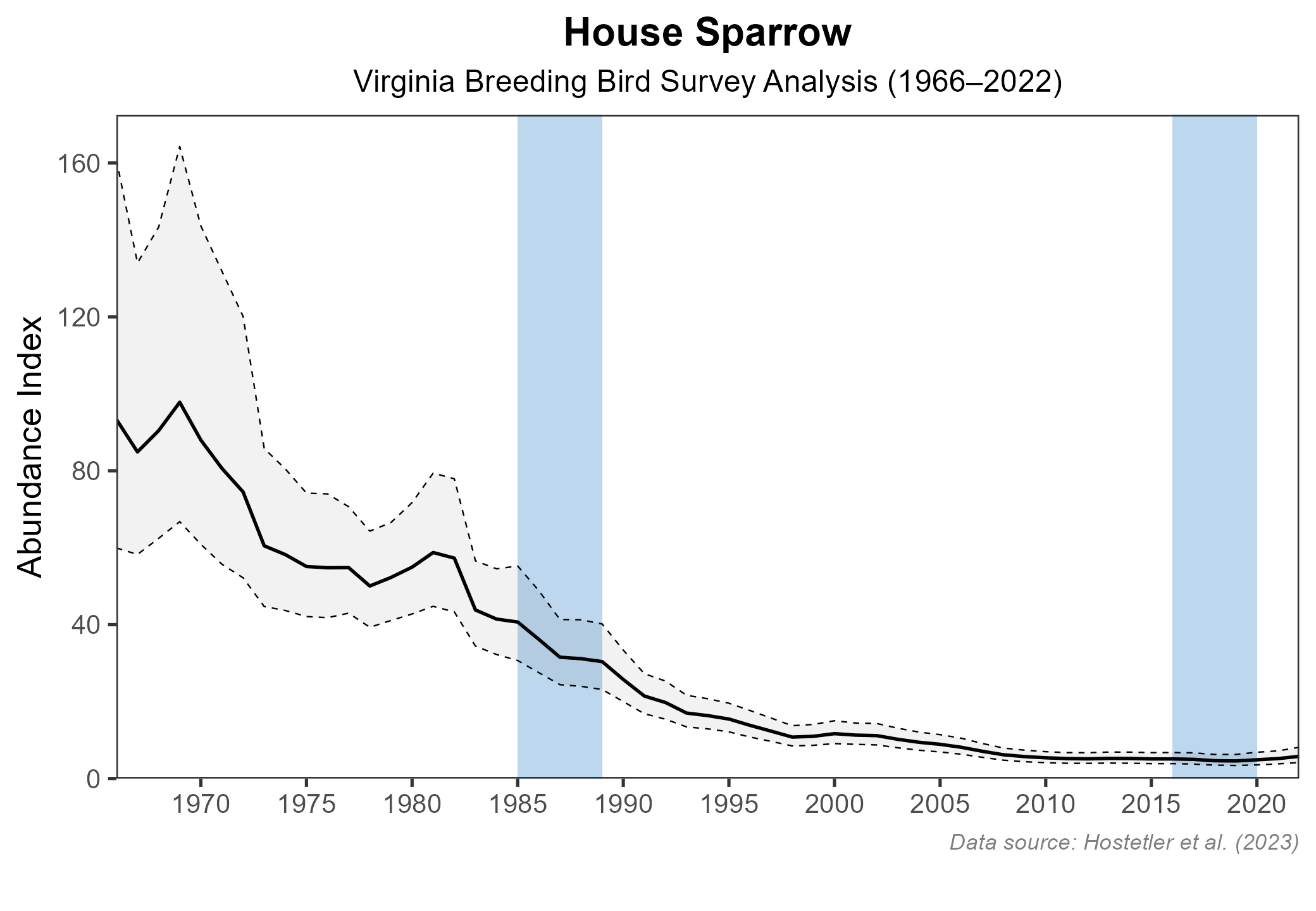

The total estimated House Sparrow population in the state is approximately 255,000 individuals (with a range between 189,000 and 345,000). Population trends for the species are decreasing in Virginia. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) indicates that the population trend in the state experienced a significant decrease of 4.85% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 8). Between Atlas periods, the population trend showed an even steeper significant decline of 5.99% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 7: House Sparrow relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 8: House Sparrow population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Because House Sparrows are an introduced species in Virginia, they are not the focus of conservation efforts and are not protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act or other laws. In fact, control of House Sparrow populations is a common objective of efforts to protect nesting native species such as Eastern Bluebirds. Despite widespread declines, the House Sparrow will likely remain a familiar bird in urban environments: at the time of writing, there is a pair nesting in the author’s dryer vent.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Bailey, H. H. (1913). The birds of Virginia. J.P. Bell Company, Incorporated. Lynchburg, VA, USA.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Lowther, P. E., and C. L. Clink (2020). House Sparrow (Passer domesticus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.houspa.01.

Robbins, C. S. (1973). Introduction, spread, and present abundance of the House Sparrow in North America. Ornithological Monographs 14:3–9. https://doi.org/10.2307/40168051.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.