Introduction

The Field Sparrow is a widely distributed North American sparrow commonly found in old fields and scrubby secondary growth. Its washed-out gray-and-rusty plumage, along with its bright pink bill and legs, make it stand out from other sparrows. More notable than its appearance, however, is its song, an accelerating bouncing-ball trill. In Virginia, Field Sparrows inhabit diverse environments, from vacant lots to reclaimed mined lands. As partial migrants, some winter birds migrate from northern ranges, while some summer breeders depart in winter (Carey et al. 2020). Other individuals are permanent residents. Their long-term population trends in the state (see Population Status) highlight the consequences of habitat change on shrubland birds.

Breeding Distribution

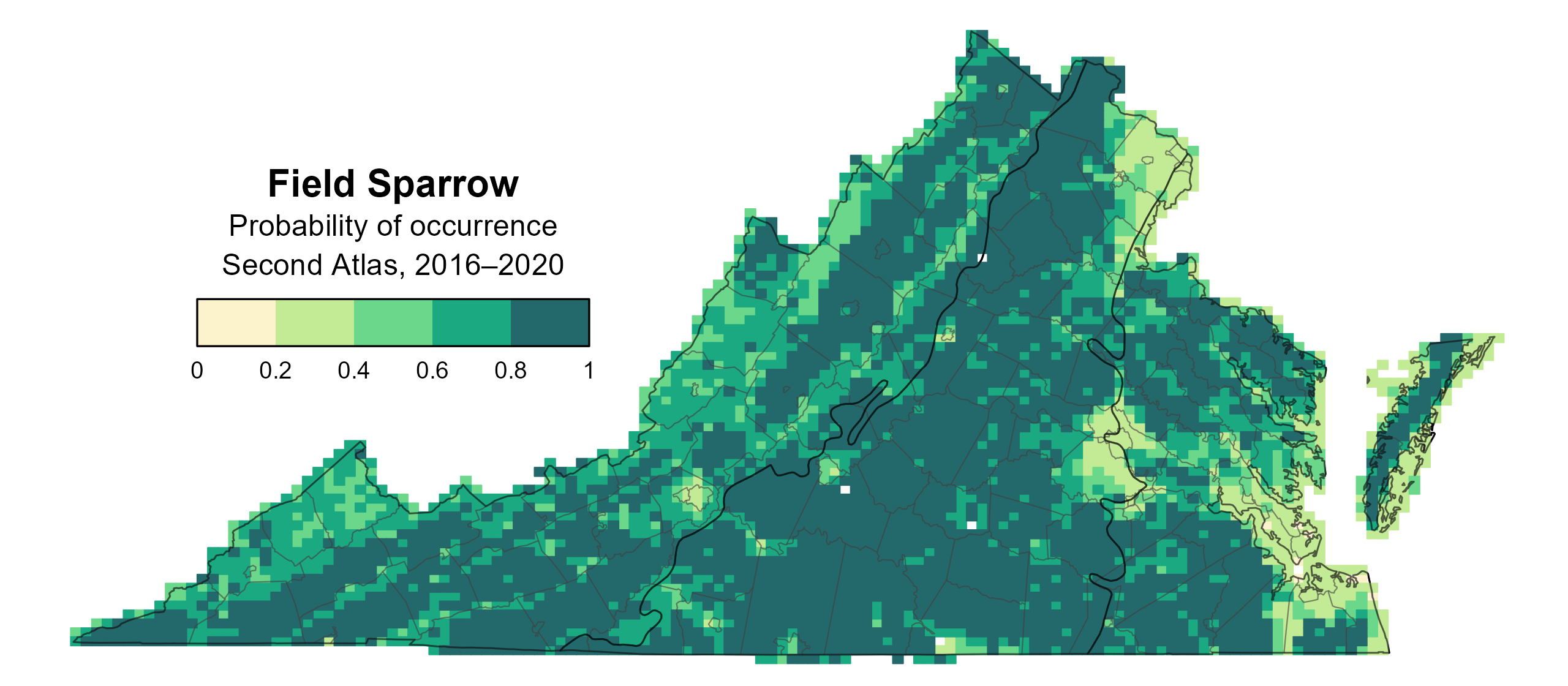

Field Sparrows are found in all regions of the state in most non-forested areas outside urban centers (Figure 1). More specifically, they are most likely to occur in the central portion of the Mountains and Valleys region and in the Piedmont region, except around the highly developed areas of Richmond and Northern Virginia. They are slightly less likely in the Coastal Plain and parts of the Eastern Shore; however, even in these areas, they are moderately likely to occur, indicating that a large scrubby field could easily host the species. The likelihood of a Field Sparrow occurring in a block increases sharply with the proportion of agricultural land (which includes hay fields and pastures). They are also more likely to occur in blocks with more shrubland and forest cover; while they do not nest in forest, they commonly use forest edges. Occurrence is less likely in blocks with a greater diversity of habitat types.

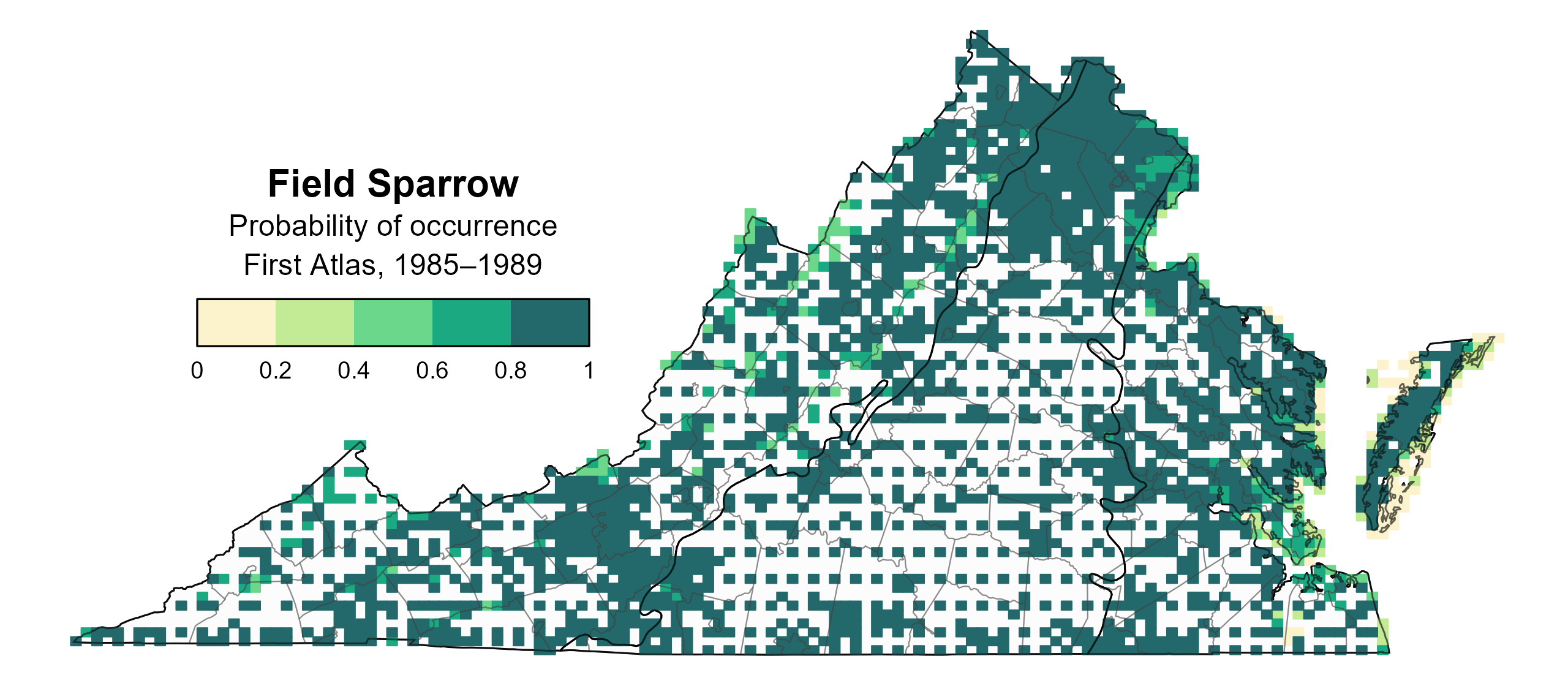

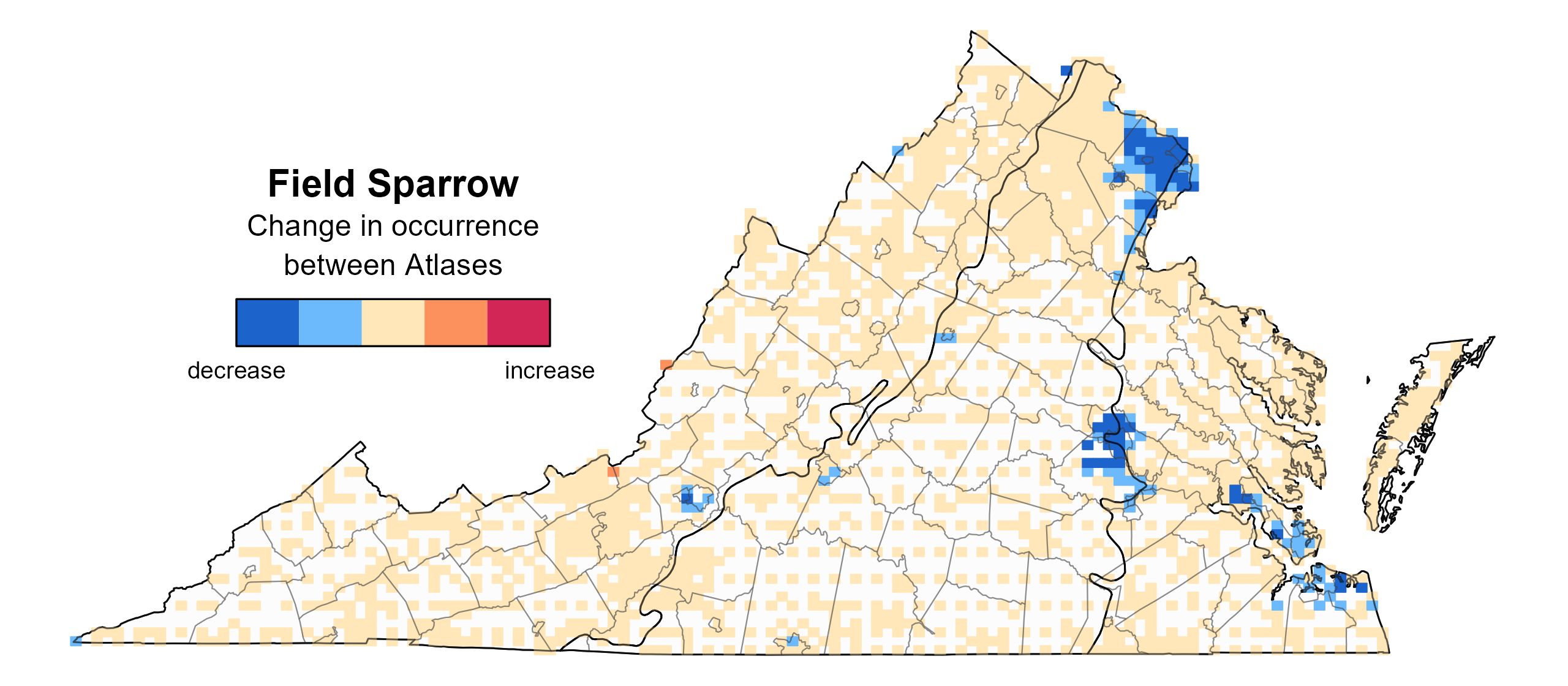

Field Sparrow occurrence in the Second Atlas was largely similar to that in the First Atlas (Figure 2). However, the Field Sparrow’s occurrence decreased in urbanized areas, especially in Hampton Roads, Richmond, and Northern Virginia (Figure 3). These areas have experienced an increase in urban cover since the First Atlas. Because Field Sparrows will not nest close to human structures (Carey et al. 2020), the replacement of agricultural (hay and pasture) and shrubland habitat with expanding urban and suburban areas has reduced the availability of suitable Field Sparrow habitat. Its probability of occurrence remained otherwise constant across most of the state. Notably, trends in abundance reflect a steady, widespread decline in numbers that may not be reflected in their overall presence versus absence (see Population Status).

Figure 1: Field Sparrow breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Field Sparrow breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Field Sparrow change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

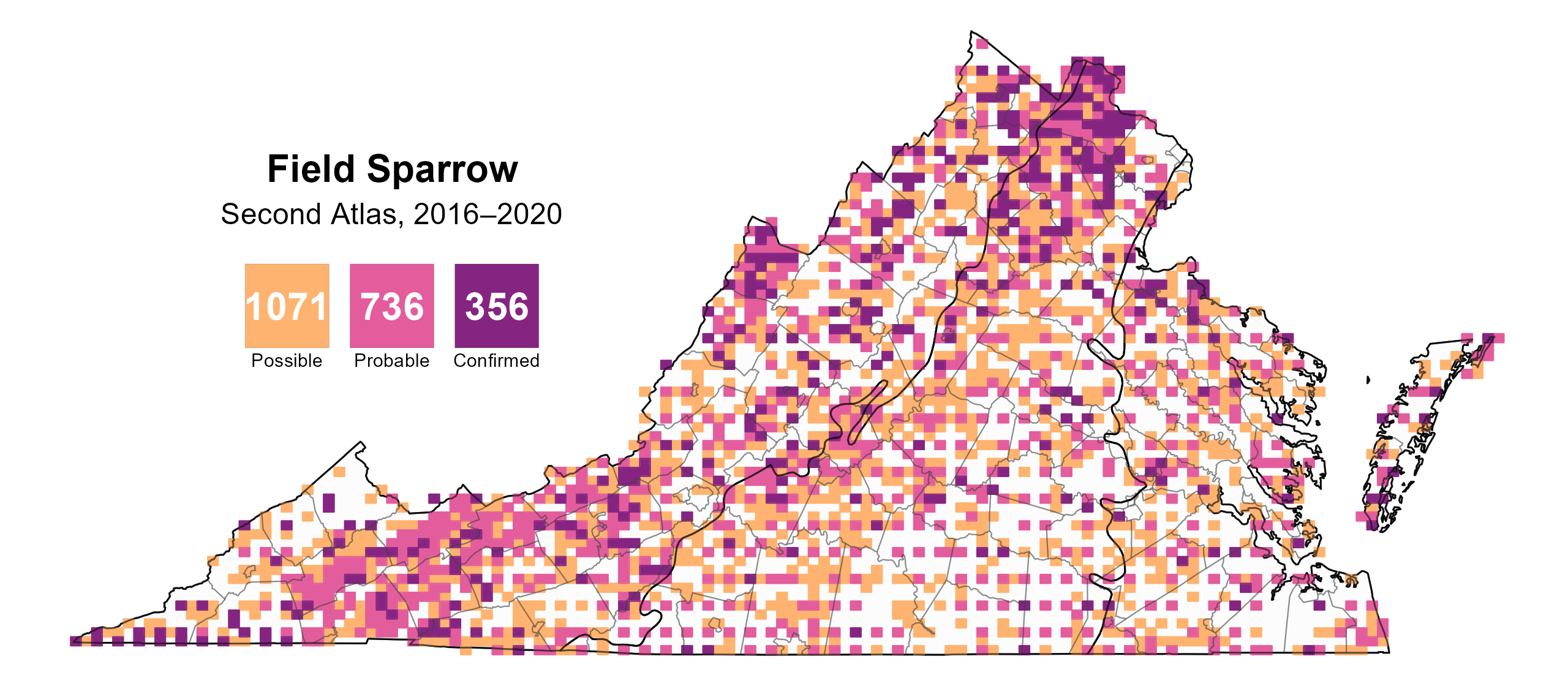

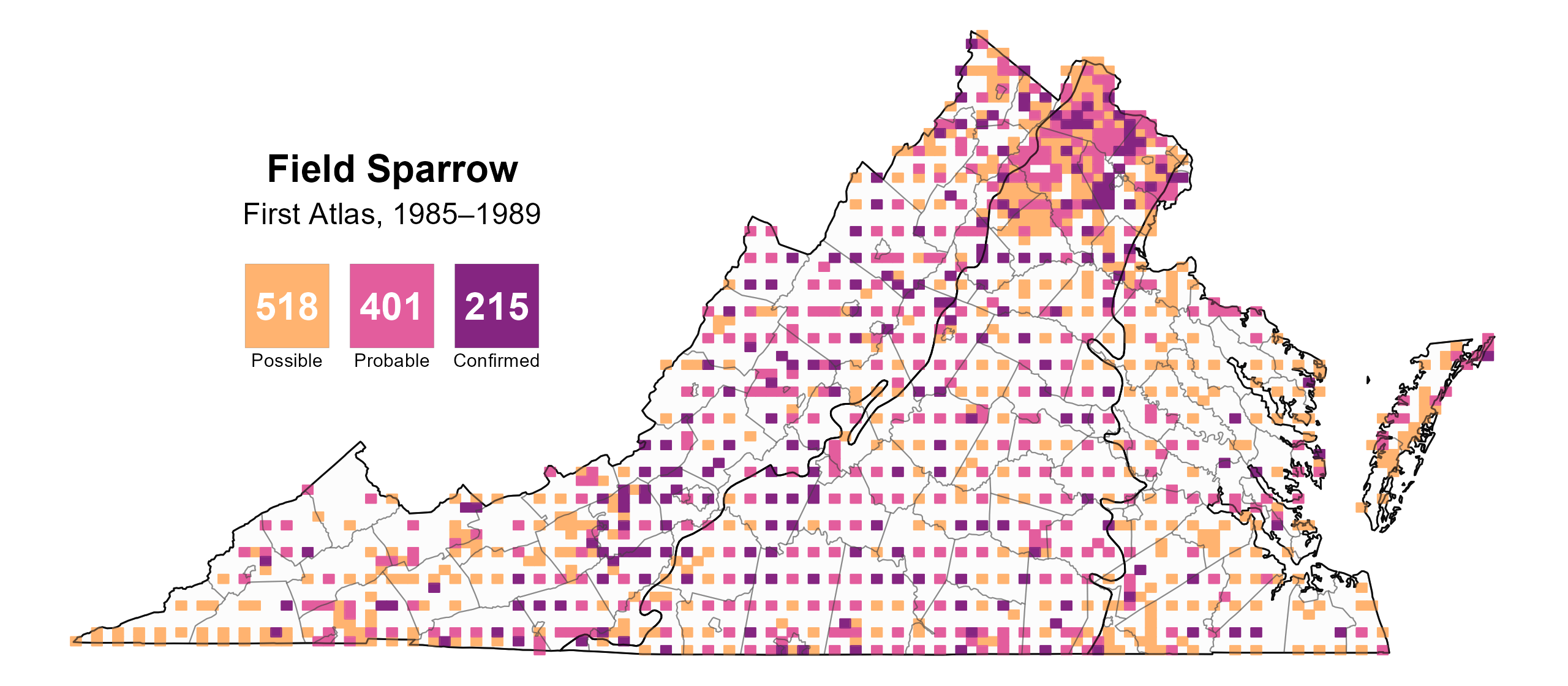

Field Sparrows were confirmed breeders in 356 blocks and 86 counties and probable breeders in an additional 22 counties (Figure 4). Field Sparrows were confirmed breeders throughout the state during the First Atlas as well (Figure 5).

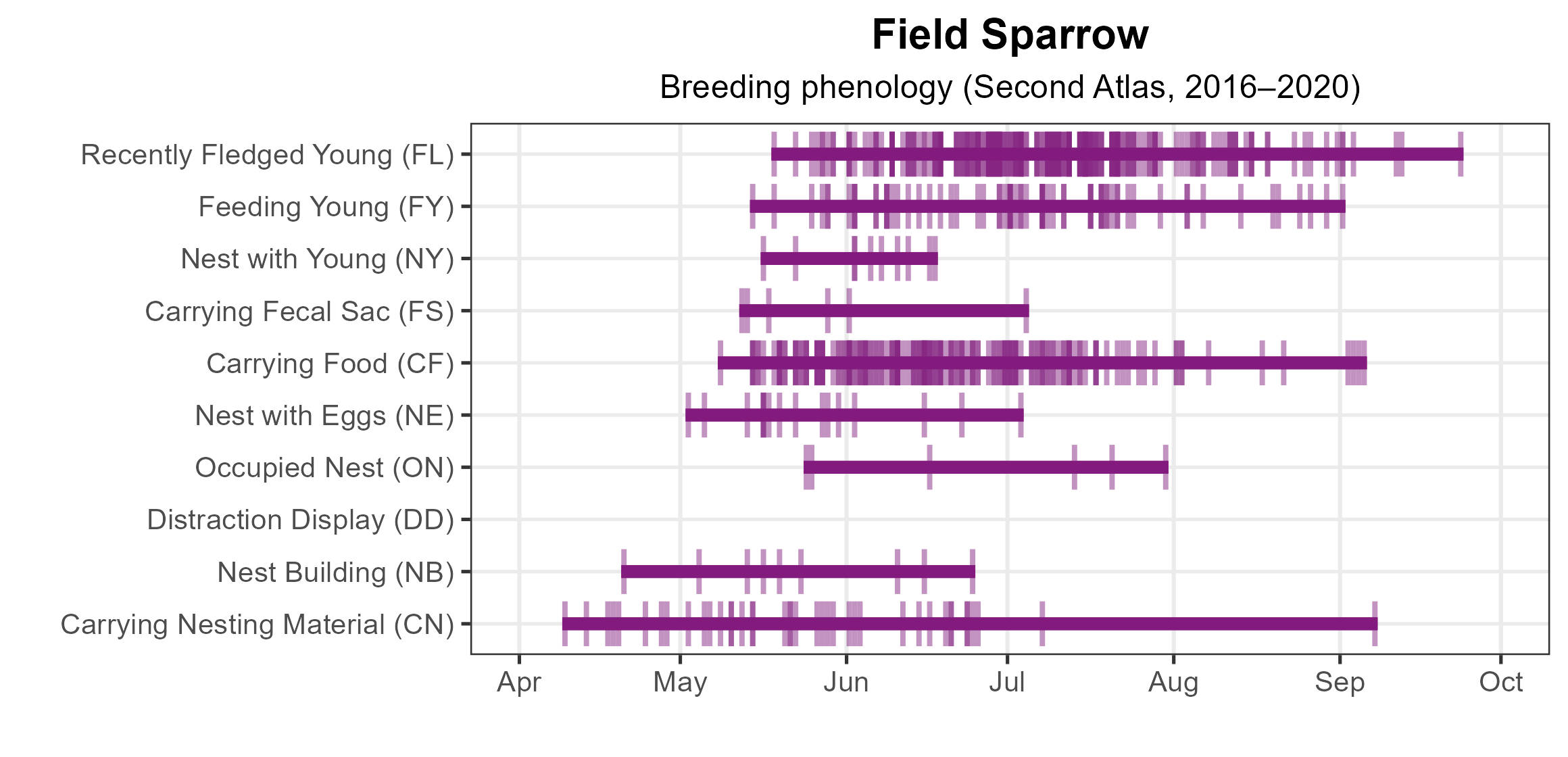

Because Field Sparrows typically nest in scrubby but walkable fields and are not as secretive as other grassland birds, they were commonly observed, with over 230 observations of fledglings. Birds began constructing nests from April 9, and breeding continued through early fall, with fledglings seen as late as September 23 (Figure 6). For more general information on the breeding habits of the Field Sparrow, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Field Sparrow breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Field Sparrow breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Field Sparrow phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

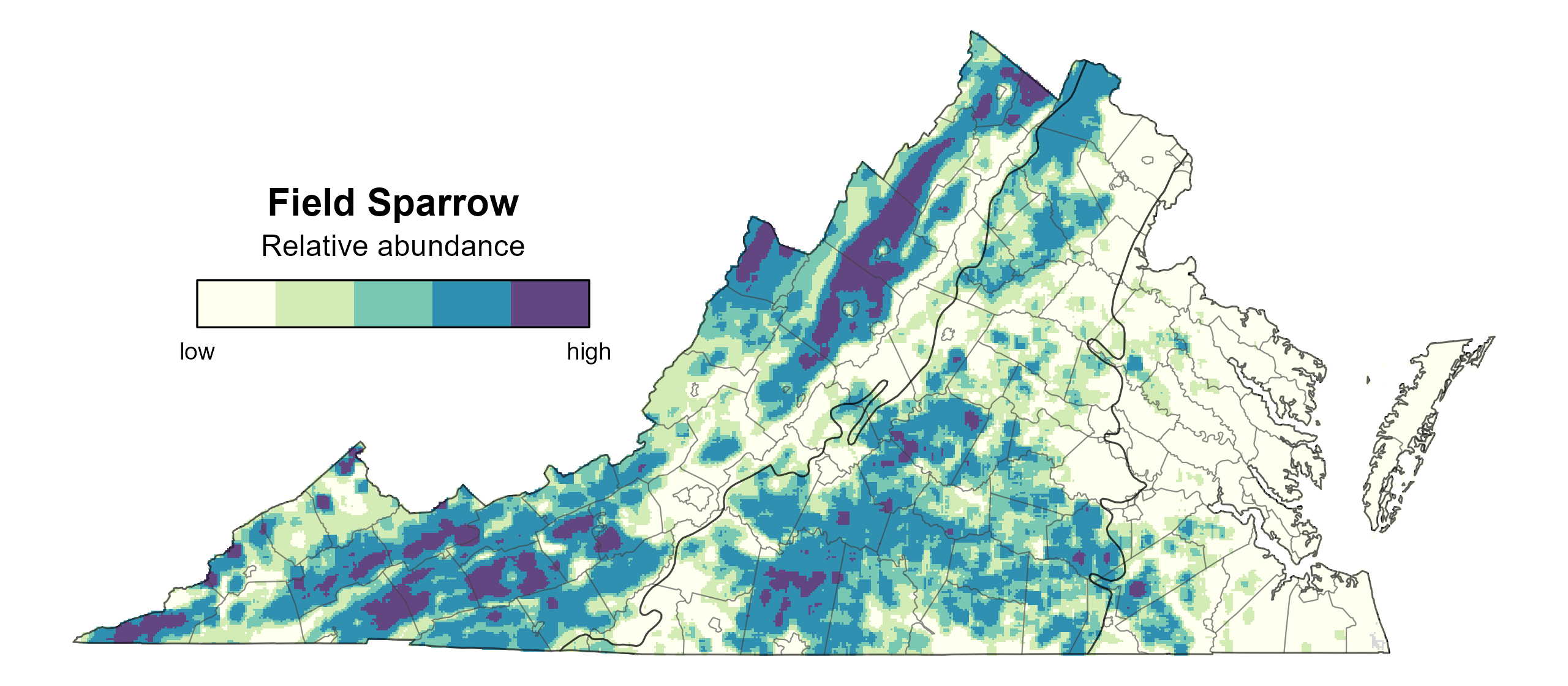

Field Sparrow relative abundance was estimated to be highest in the agricultural mountain valleys and throughout the Piedmont region where agricultural, grassland, and shrubland habitats exist on the landscape (Figure 7). Throughout the remainder of the state, their abundances levels were predicted to be moderate to low.

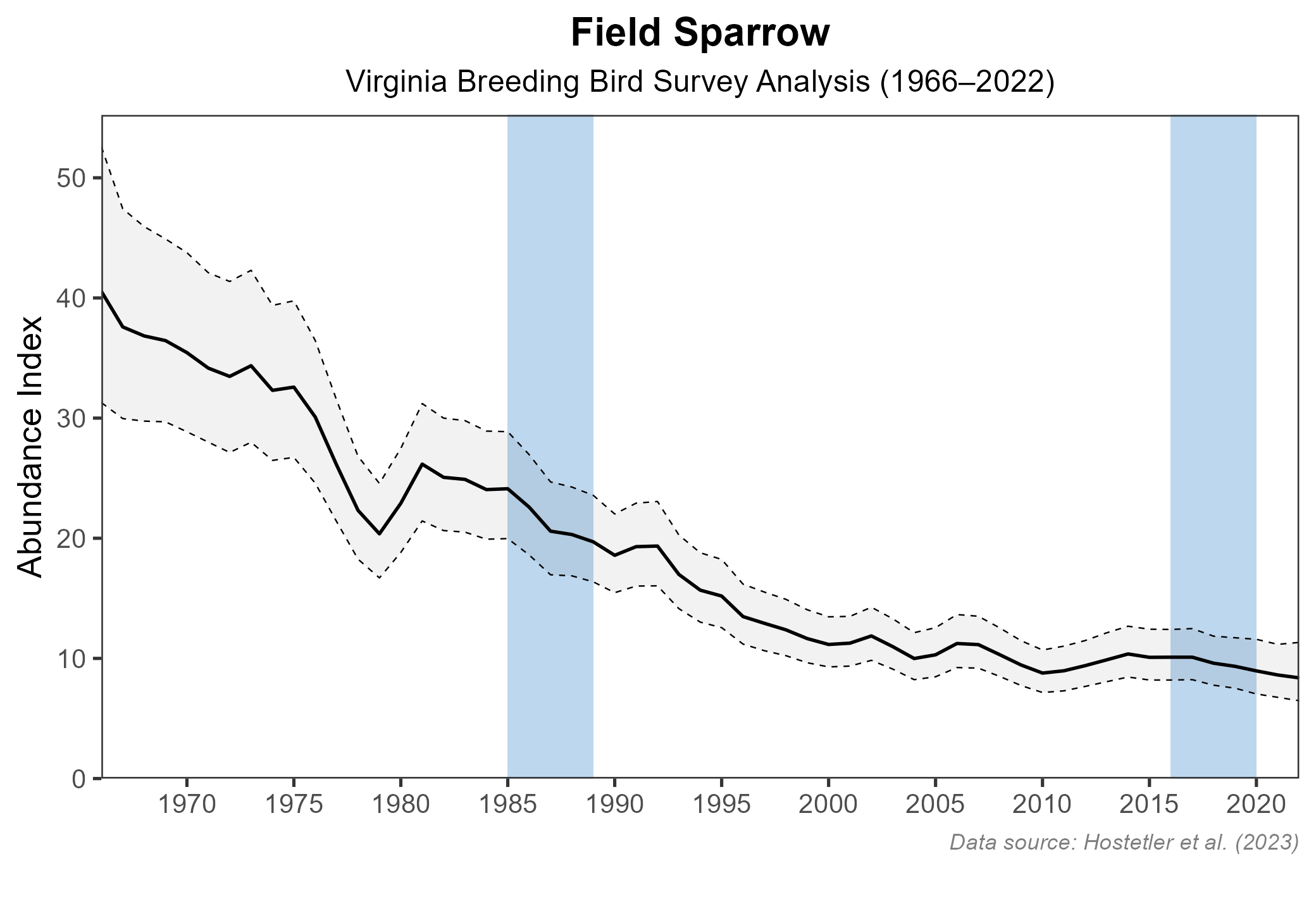

The total estimated Field Sparrow population in the state is approximately 442,000 individuals (with a range between 356,000 and 552,000). Despite their widespread and abundant nature, Field Sparrow populations are declining in Virginia. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) showed a significant decline of 2.77% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 8). Between the First and Second Atlas, BBS data showed similar declines, with a decrease of 2.44% per year in Virginia from 1987–2018.

Figure 7: Field Sparrow relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 8: Field Sparrow population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Field Sparrows are considered a “yellow alert” species on the Road to Recovery Tipping Point species list, meaning they have lost over 50% of their population in the long term, but short-term losses are not as steep. Because Field Sparrows do not breed in urban or most suburban areas, habitat loss is the major driver of their decline. Given their decline, the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan includes them as Tier IV Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Moderate Conservation Need) (VDWR 2025).

To protect them, maintaining shrubland habitats, particularly fields with some woody vegetation, is crucial for their conservation. For detailed management recommendations, see Dechant et al. (2002). Suitable habitat can be found long-term on reclaimed surface mines (Latimer 2012) and powerline cuts (Carey et al. 2020), both of which remain in an early successional state for much longer than normal through arrested succession or intentional management.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Carey, Michael, D. E. Burhans, and Douglas A Nelson (2020). Field Sparrow (Spizella pusilla), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.fiespa.01.

Dechant, J. A., M. L. Sondreal, D. H. Johnson, L. D. Igl, C. M. Goldade, B. D. Parkin, and B. R. Euliss (2002). Effects of management practices on grassland birds: Field Sparrow. U.S. Geological Survey Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Jamestown, ND, USA.. https://doi.org/10.3133/93877.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Latimer, C. E. (2012). Avian population and community dynamics in response to vegetation restoration on reclaimed mine lands in Southwest Virginia. Master’s thesis. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.