Introduction

The loud and incessant vocalizations from which the Eastern Whip-poor-will derives its name are difficult to miss. However, this nocturnal bird calls most consistently on nights when the moon is bright and high in the sky (Wilson and Watts 2006), a behavior which has helped guide the timing of surveys for the species. Termed an “aerial insectivore,” the Whip-poor-will consumes flying insects, which it typically chases down from a tree perch.

Breeding Distribution

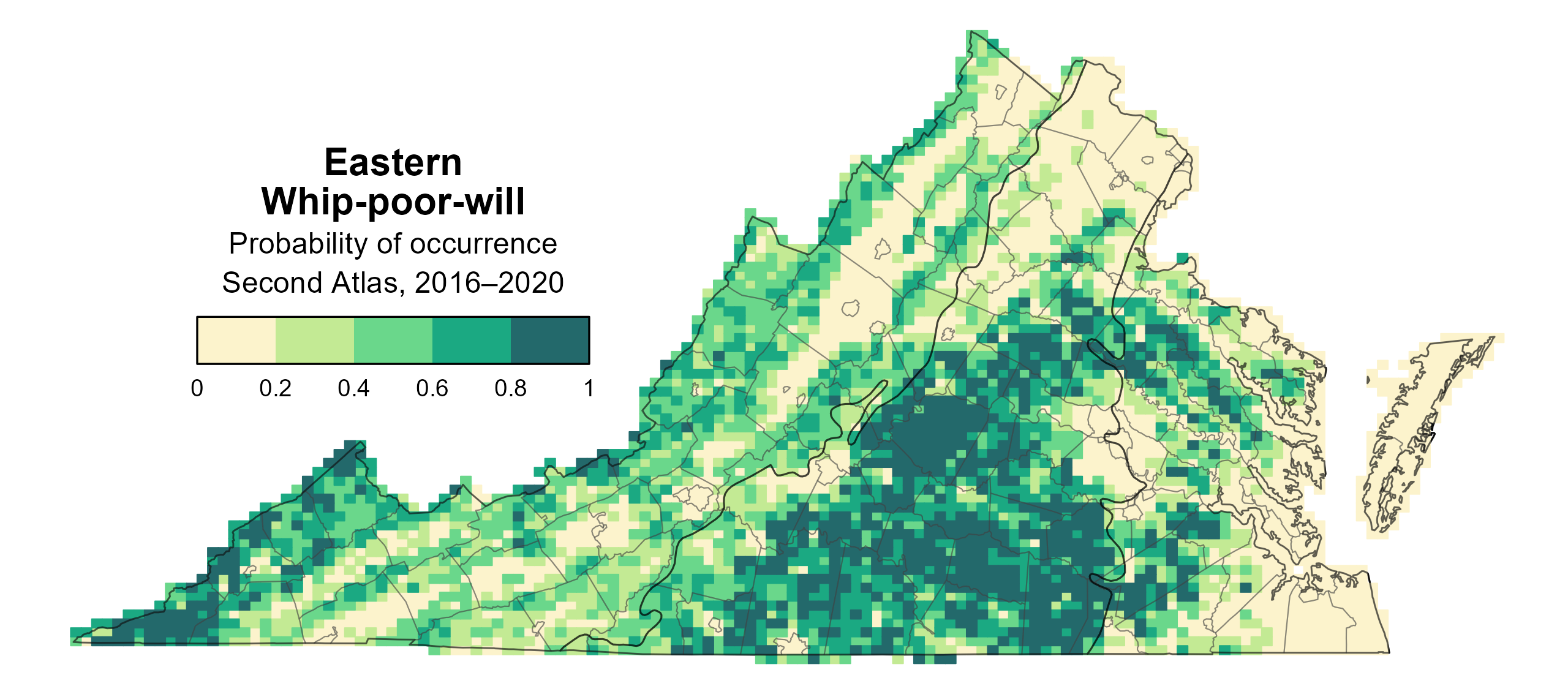

Eastern Whip-poor-wills are found in all regions of the state but are most likely to occur in the western Coastal Plain, central and southern Piedmont, and the Cumberland Mountains (Figure 1). They are more likely to be found in blocks with greater forest cover and with a greater proportion of shrubland and grassland habitats, indicating a preference for a mix of habitats, and are negatively associated with development.

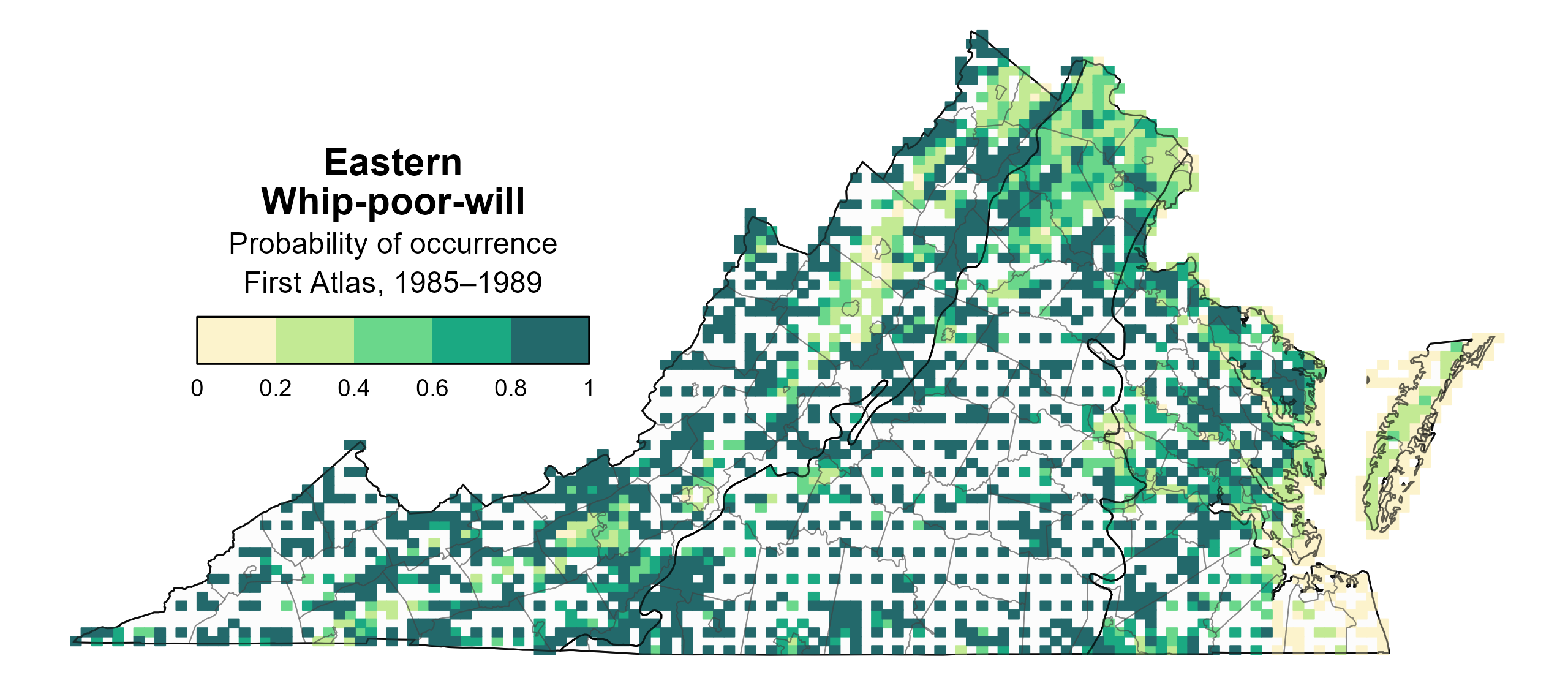

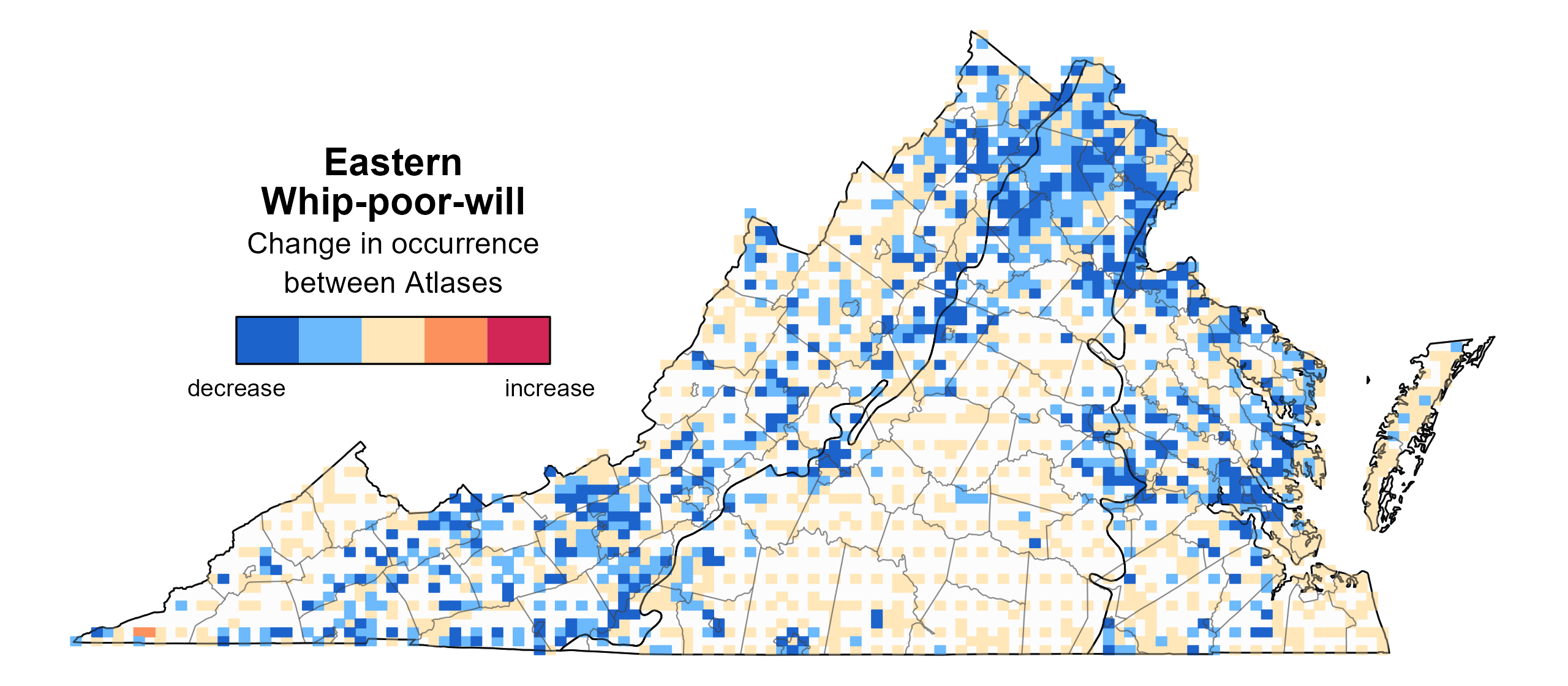

Between the First and Second Atlases (Figures 1 and 2), the Eastern Whip-poor-will’s probability of being found in a block substantially decreased through much of the state but remained constant in the central and southern Piedmont and Cumberland Mountains (Figure 3). These widespread decreases are consistent with the species’ population decline in the state (see Population Status section).

Figure 1: Eastern Whip-poor-will breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Eastern Whip-poor-will breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Eastern Whip-poor-will change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit)between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

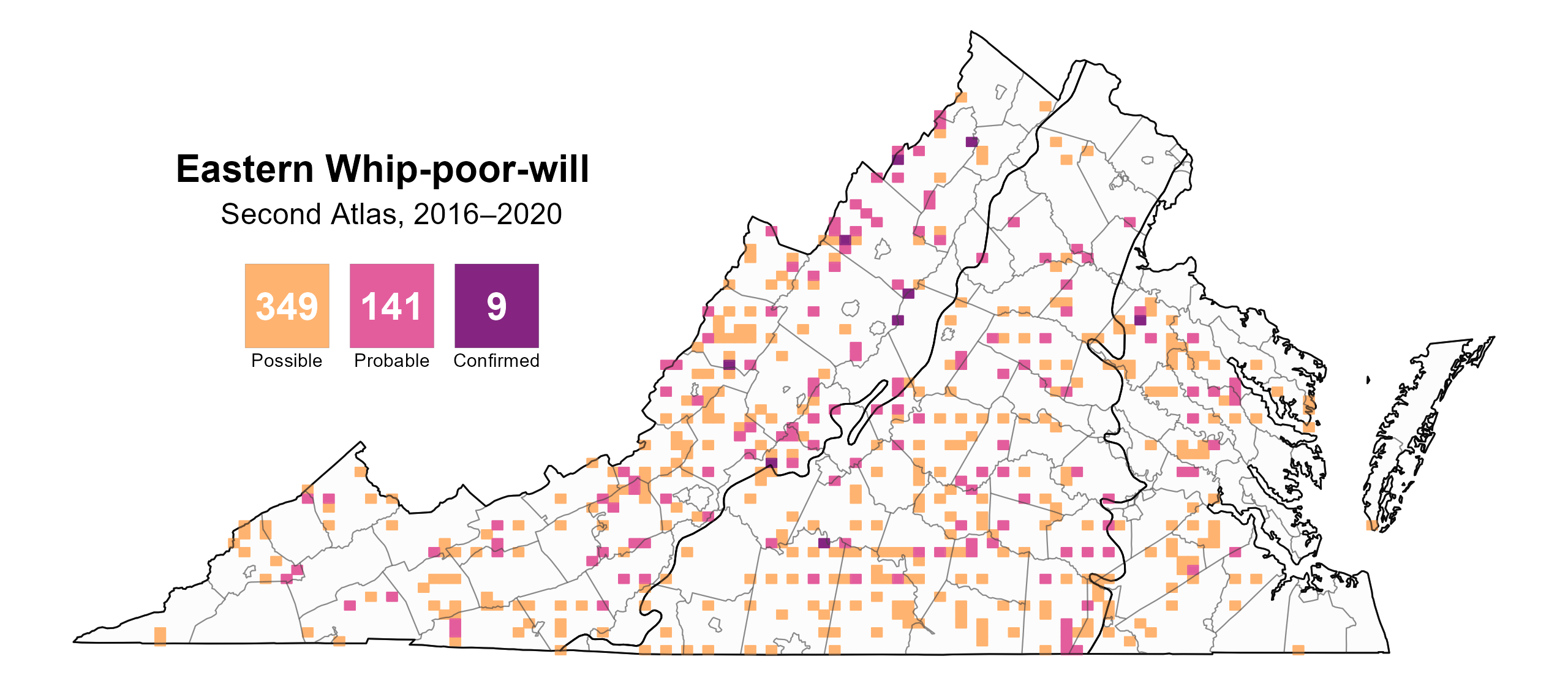

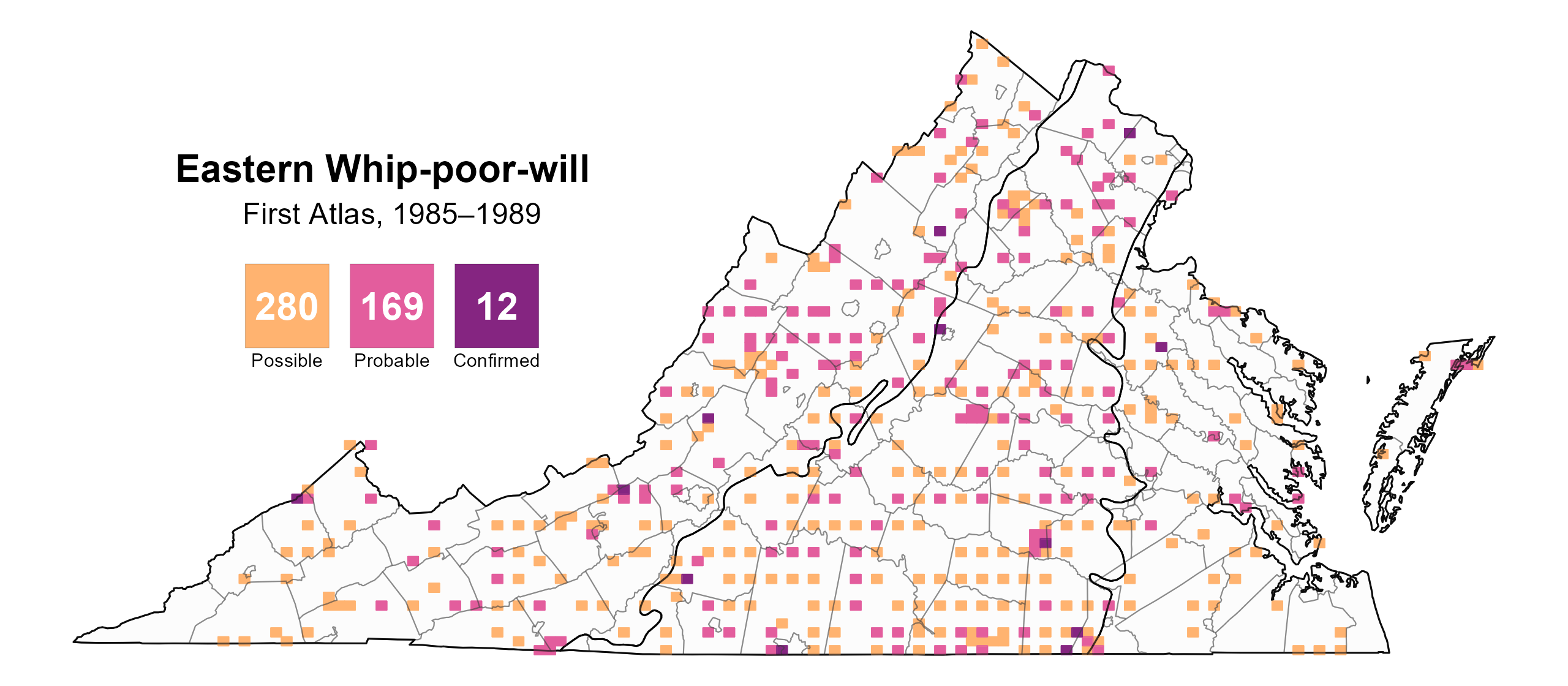

Eastern Whip-poor-wills were confirmed breeders in nine blocks and eight counties (Albemarle, Augusta, Bath, Bedford, Caroline, Pittsylvania, Rockingham, and Shenandoah) and found to be probable breeders in 51 additional counties (Figure 4). Breeding confirmations were few, due to the difficulty in observing Eastern Whip-poor-will breeding behavior at night and finding their highly camouflaged ground nests. The few observed nests were discovered when volunteers inadvertently flushed a bird that was on eggs or young. Blocks with detections were evenly distributed throughout the state, with only modest gaps occurring in extreme southwestern Virginia, the northern Piedmont, and the southeastern Coastal Plain. The number and distribution of blocks with breeding evidence were similar between Atlases (Figure 5).

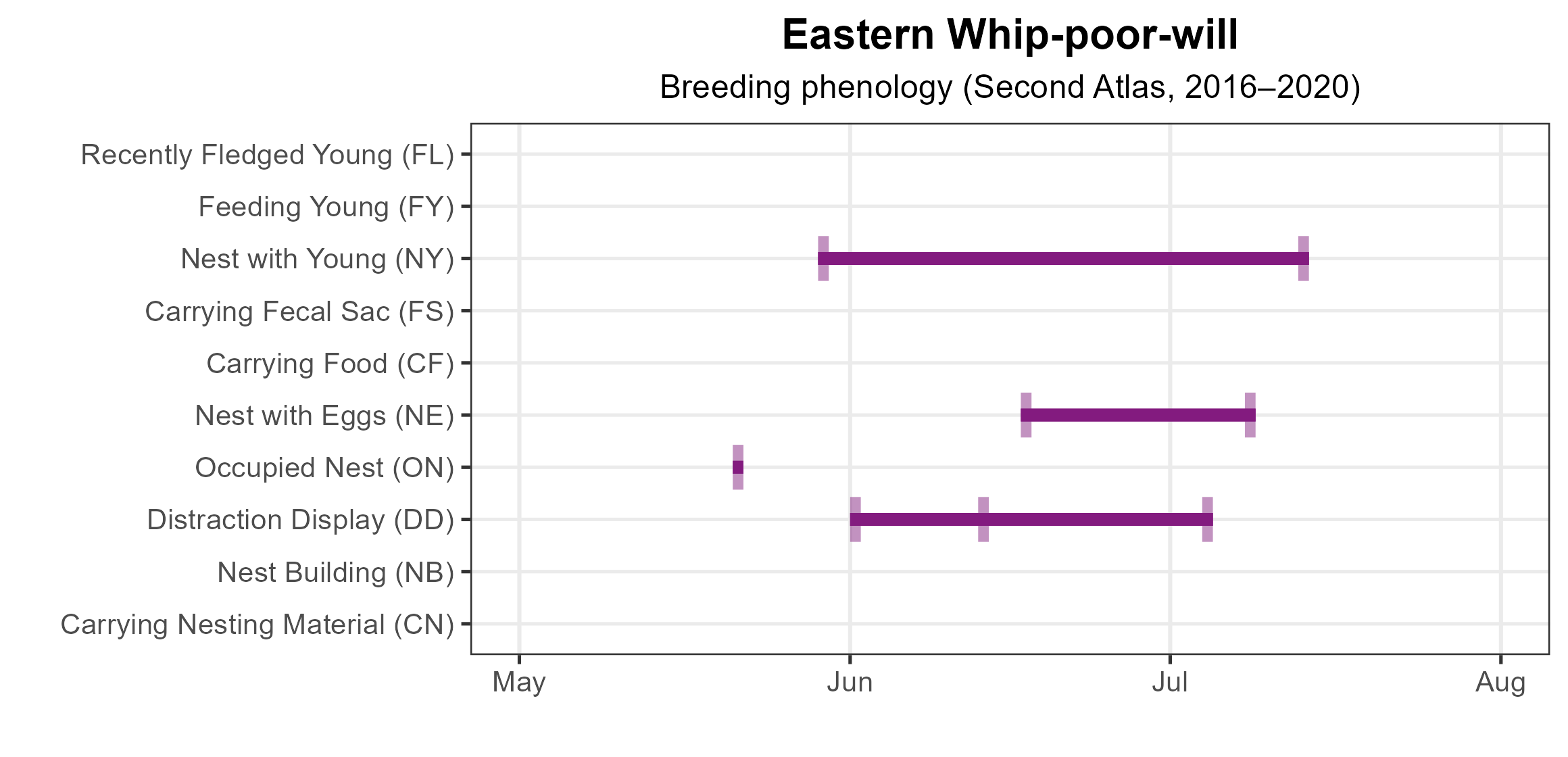

The earliest confirmation of breeding was of an occupied nest observed on May 21. Other breeding confirmations (eight in total) included observations of distractions displays (June 1 – July 4), nests with eggs (June 17 – July 8), and nests with young (May 29 – July 13) (Figure 6).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Eastern Whip-poor-will breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Eastern Whip-poor-will breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Eastern Whip-poor-will phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

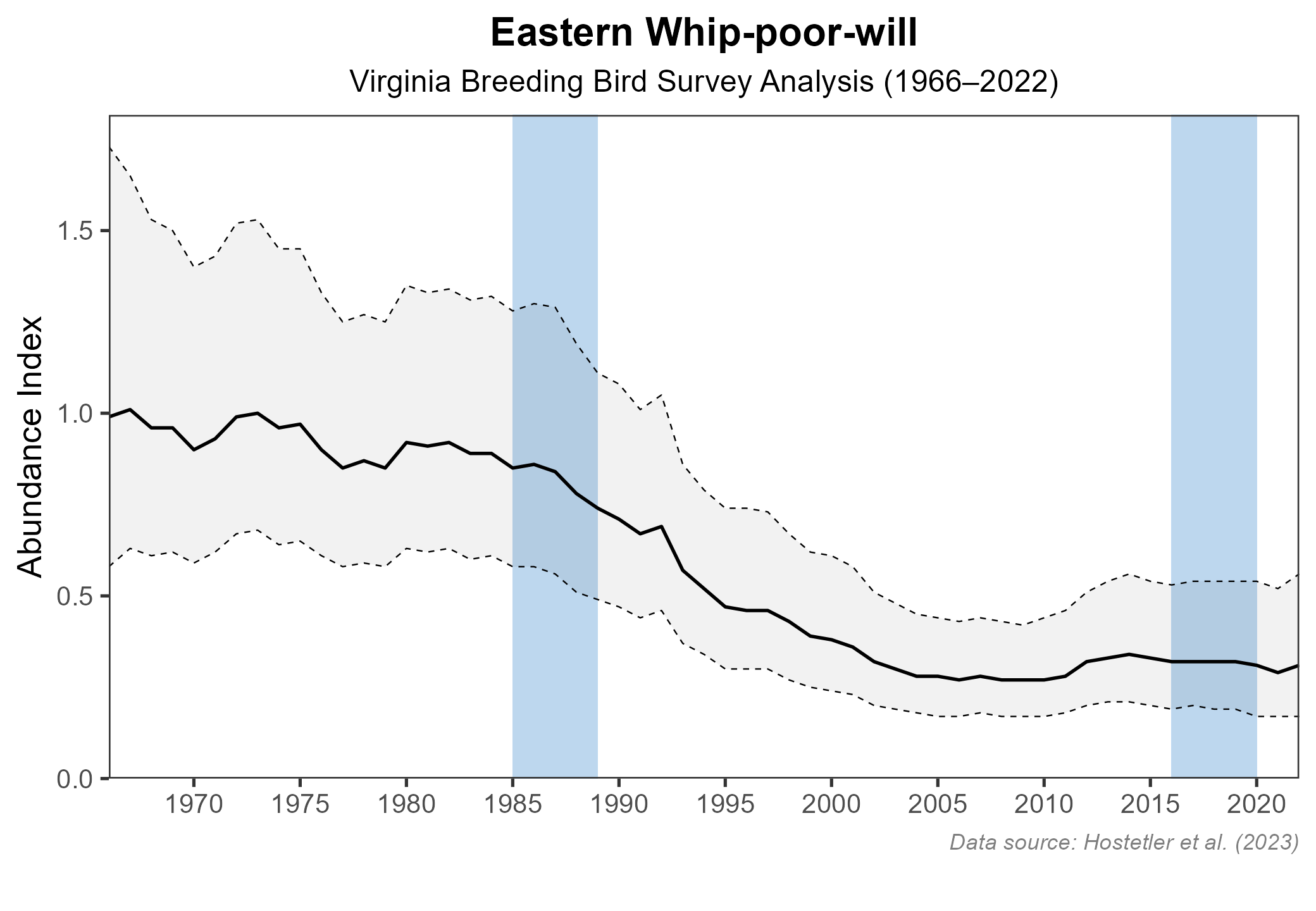

Insufficient detections during the Atlas point count surveys prevented the development of an abundance model for the Eastern Whip-poor-will. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) trend for Virginia estimated a significant decrease of 2.05% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 6). Between the First and Second Atlas, BBS data showed a slightly stronger significant decrease of 3.08% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 7: Eastern Whip-poor-will population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

While Eastern Whip-poor-wills remain common throughout their range, they have experienced a steady decline in Virginia and elsewhere. Because of this decline, the 2025 Wildlife Action Plan includes the Eastern Whip-poor-will as a Tier III (High Conservation Need) Species of Greatest Conservation Need (VDWR 2025).

Whip-poor-wills nest in deciduous and mixed forests with open understories (Cink et al. 2020). They may use a variety of additional open habitats for foraging, including nearby fallow fields, croplands, shrublands and regenerating pine stands (Wilson and Watts 2008). They can ultimately benefit from conservation, restoration, and management of forests with the appropriate degree of openness and with proximity to open habitats. Potential threats to such habitat conditions include the loss of shrubland and grasslands to human development, changes in farming practices, and forest regrowth (Cink et al. 2020; Tosa et al 2025). However, it is unknown whether the reasons for declines in the species are directly habitat-based or due to other causes, including human impacts on their insect prey base through land alterations and the use of pesticides (Tosa et al. 2025).

Further investigations are necessary and should include movement tracking studies to determine where Virginia birds overwinter, as a path toward assessing potential threats to their populations during the nonbreeding season. Volunteer participation in the Nightjar Survey Network (Tosa et al. 2025) should be encouraged to generate more accurate population trend information than what is currently provided by the BBS.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Cink, C. L., P. Pyle, and M. A. Patten (2020). Eastern Whip-poor-will (Antrostomus vociferus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.whip-p1.01.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Tosa, M. I., A. J. Roberts, A. K. Tegeler, P. K. Devers, L. A. M. Parker, P. D. Hunt, B. D. Watts, M. Huang, A. C. Vitz, S. H. Schweitzer, S. Robinson, M. D. Palumbo, and R. Rebozo (2025). Design of a monitoring program to advance nightjar conservation along the Atlantic Flyway. Wildlife Society Bulletin 49:e1581. https://doi.org/10.1002/wsb.1581.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Wilson, M.D. AND B.D. Watts. 2006. Effect of moonlight on detection of Whip-poor-wills: implications for long-term monitoring strategies. Journal of Field Ornithology 77:207–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1557-9263.2006.00042.x.

Wilson, M.D. and B.D. Watts. 2008. Landscape configuration effects on distribution and abundance of Whip-poor-wills. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 120:778–783.