Introduction

Few species are as loved or hated as the humble Canada Goose, yet the history of the species’ different subpopulations is often misunderstood. In the early 20th century, all the Canada Geese found in Virginia were migratory birds that flew north in the spring to nest in northern Canada. In the fall, they migrated back south to winter in Virginia and along the Atlantic Coast. This population increased gradually from the 1940s through the 1980s, as the birds adapted to feeding in agricultural fields. This foraging shift provided a wealth of habitat in addition to the marshes and shallow water areas they had traditionally used for feeding. Their numbers declined in the early 1990s due to several years of poor reproductive success on the breeding grounds, combined with continued harvests. Their numbers recovered in the early 2000s and have been relatively stable since then.

In addition to migrant geese, local breeding populations of Canada Geese began appearing in Virginia, and other U.S. states, in the 1940s as farm-raised birds and live birds used for hunting decoys were released into the wild. Their numbers increased from the 1960s through the 1990s, as they adapted to man-made habitats that included grassy lawns, suburban lakes, and residential neighborhoods. These birds generally stay in Virginia year-round and are considered descendants from a nonmigratory population of the Giant Canada Goose subspecies Branta canadensis maxima (Mowbray et al. 2020). They have become so abundant and accustomed to people that they are now referred to as “resident geese” and are classified as “nuisance and problem wildlife” in some areas. They often cause damage to urban landscaping and leave droppings on lawns and other public areas. They are also fiercely protective of their young, a trait that has contributed to both their success and frequent conflicts with people.

Breeding Distribution

“Resident” Canada Geese occur in all regions of the state. They are common in urban areas of Northern Virginia, Richmond, and Hampton Roads (Figure 1). In contrast, they are less likely to occur in the southern Piedmont and the forested highlands of the Mountains and Valleys region, where they are largely restricted to valleys and towns with abundant farm ponds, wetlands, and stormwater retention ponds. They are most likely to occur in blocks with more development and less likely to occur in those with forest.

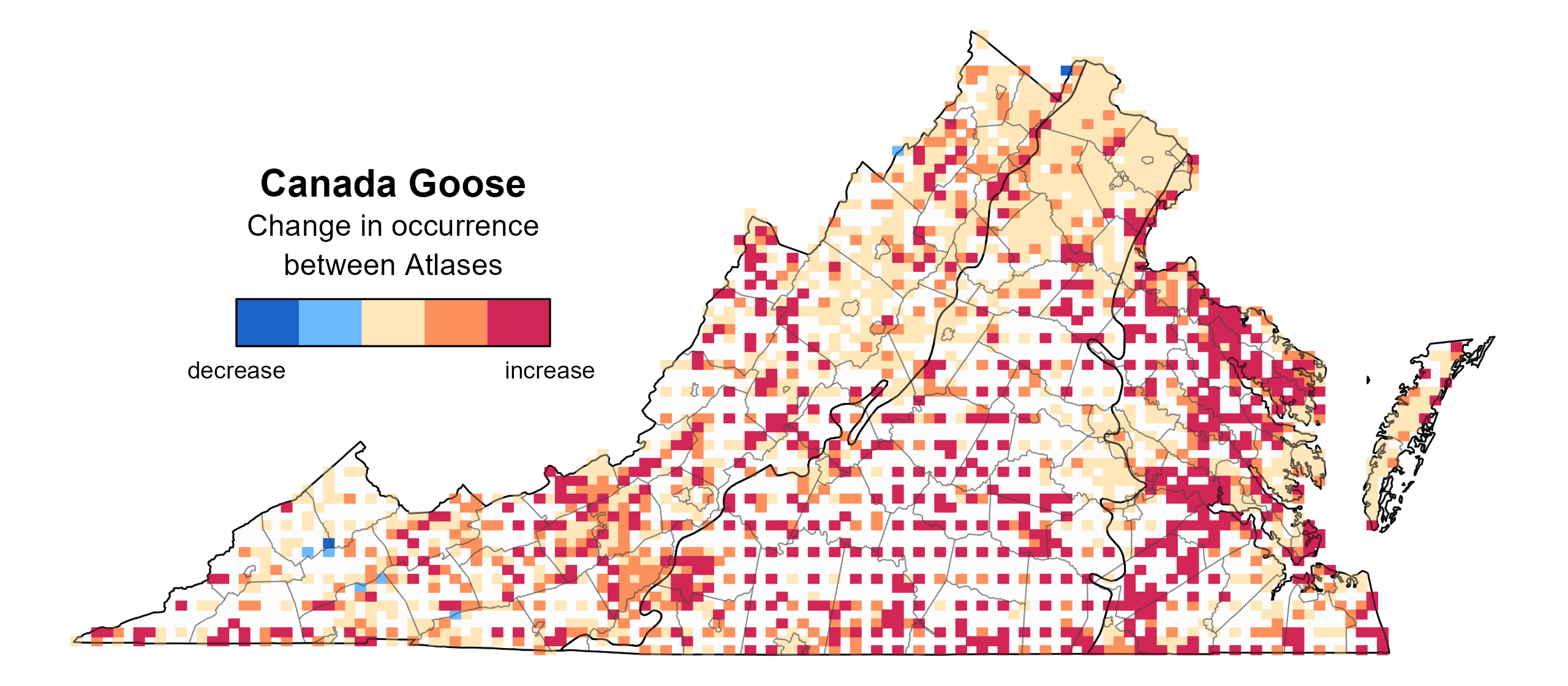

In conjunction with increasing population trends (see Population Status section), the Canada Goose’s likelihood of occurring in the Second Atlas greatly increased from that in the First Atlas (Figures 1 and 2). In fact, Canada Goose likelihood of occurring in a block increased across most of the state, except in already-saturated areas such as the northern Piedmont region, where it occurrence remained constant (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Canada Goose breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Canada Goose breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Canada Goose change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

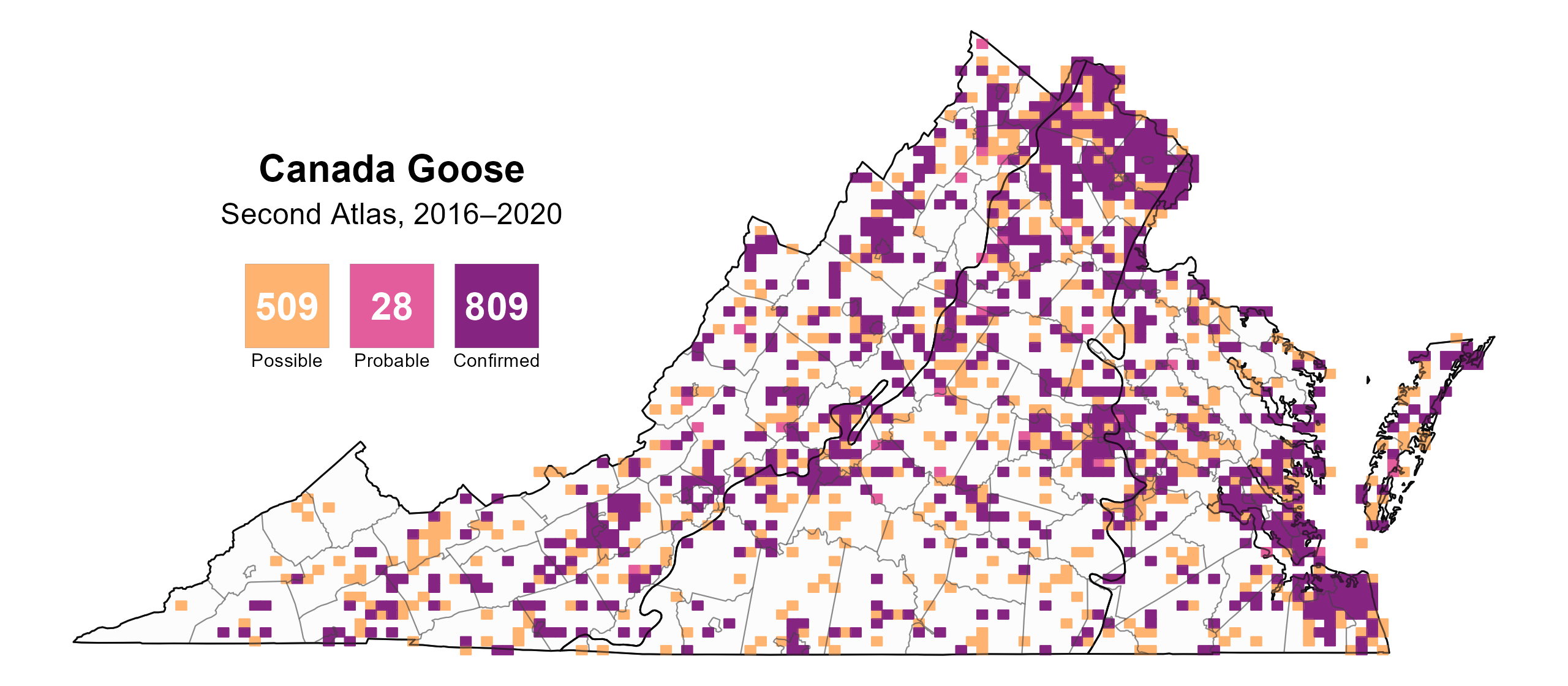

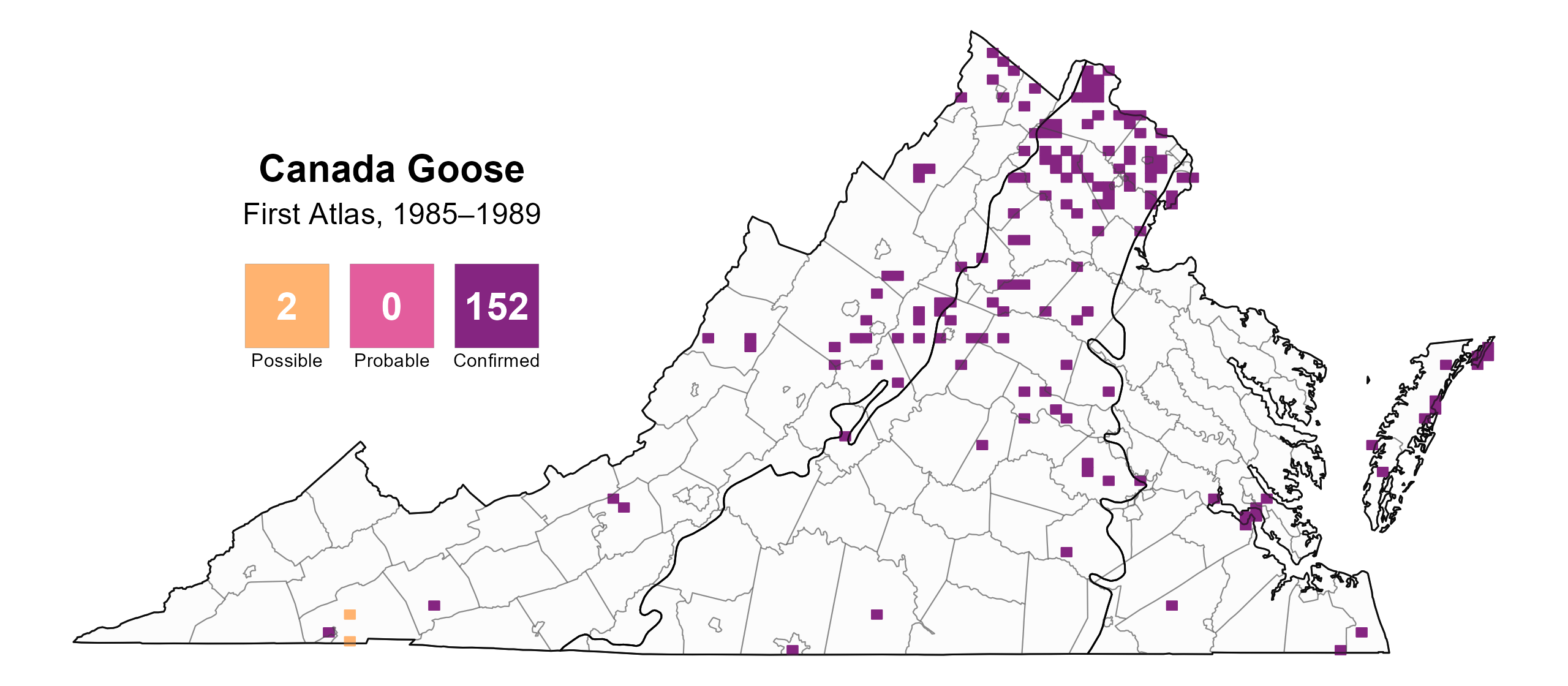

Canada Geese were confirmed breeders in 809 blocks and nearly every county in the state (123 out of 133) (Figure 4). While the species was already present across all three regions of the state during the First Atlas, breeding was confined to a limited number of sites outside of those in Northern Virginia (Figure 5). Since then, rapid population growth (see Population Status section) has driven expansion.

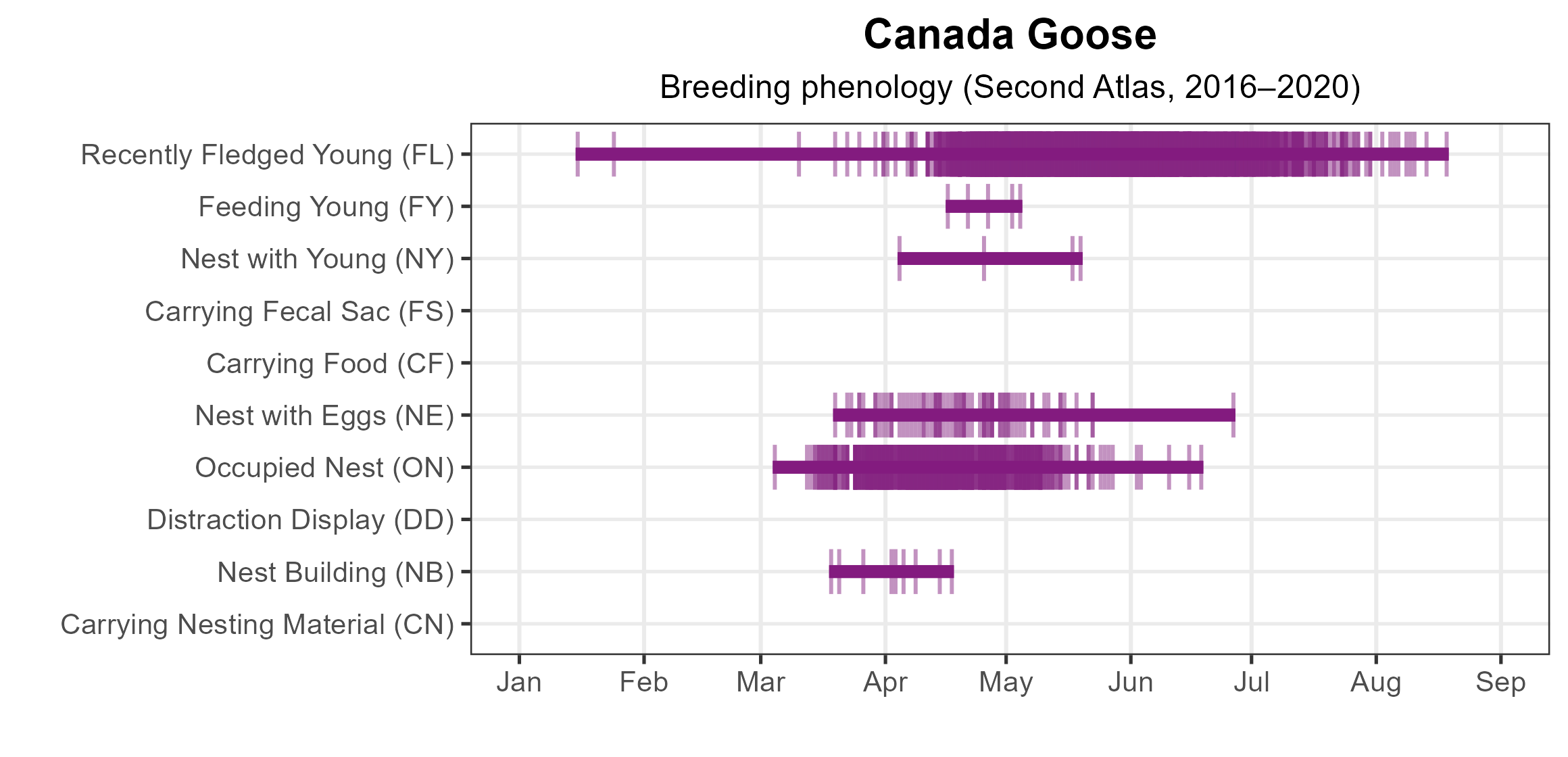

Canada Geese are among the easiest species to confirm as breeders due to their conspicuous occupied nests (609 reports) and highly visible recently fledged young (2,184 reports). Most nesting occurs from late March to early May, though records extend well beyond this period (Figure 6). The earliest outlier, a pair photographed with downy young on January 15, 2020, in Chesapeake, indicates an expanding breeding season where exceptionally warm temperatures allow it. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Canada Goose, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Canada Goose breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Canada Goose breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Canada Goose phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Canada Goose relative abundance was estimated to be highest in the Hampton Roads-Virginia Beach area and along the coastline, decreasing westward across the Coastal Plain region (Figure 7). Low relative abundance levels were estimated for most of the Piedmont region and all the Mountains and Valleys region (Figure 7).

The total estimated Canada Goose population in Virginia is approximately 57,000 individuals (with a range between 27,000 and 120,000). However, the point count surveys performed for the Atlas did not provide ample coverage for this widely distributed but low breeding-density species; thus, there is a broad range around that estimate.

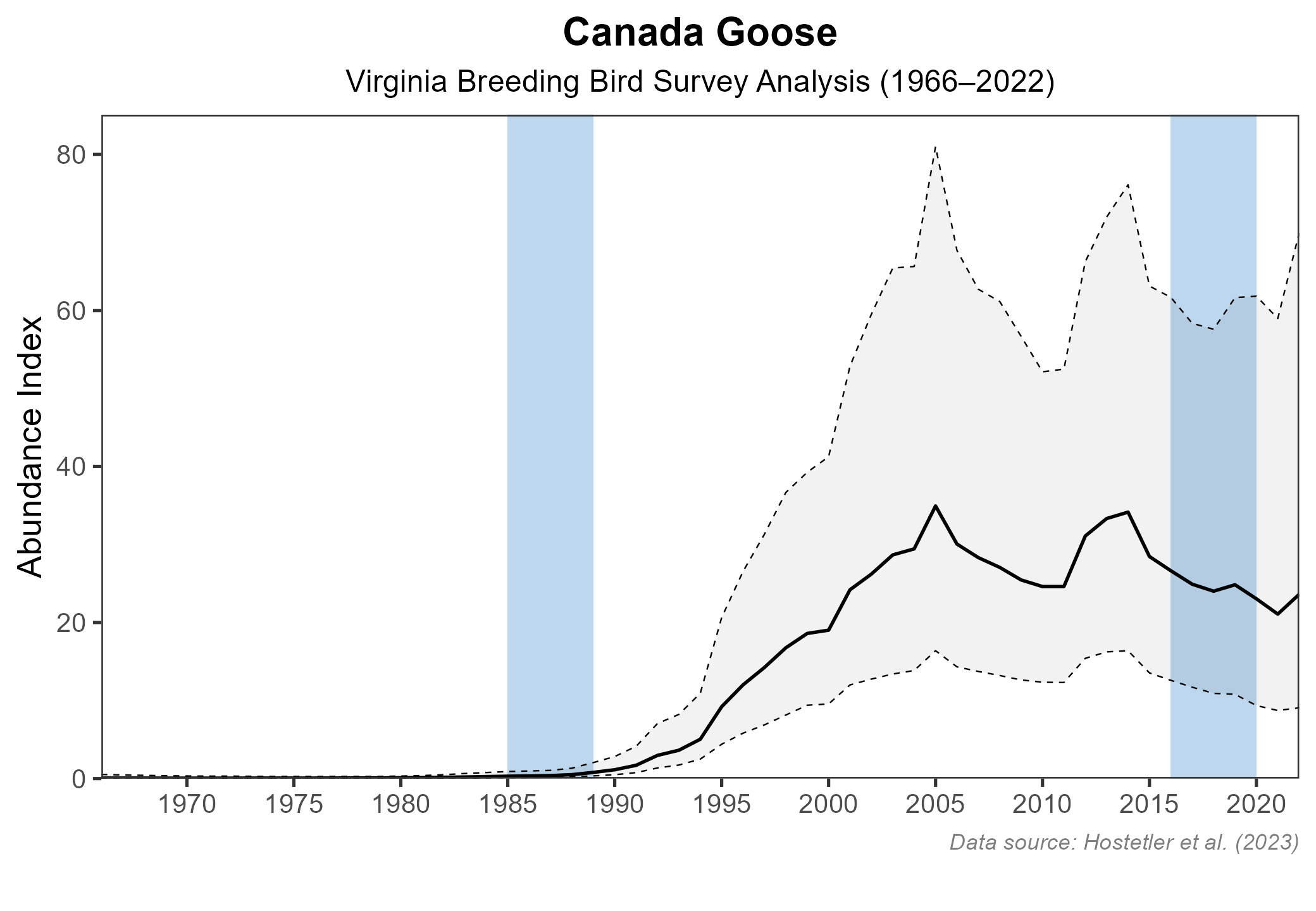

Canada Goose populations have increased significantly in Virginia. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) showed a statistically significant increase of 11.27% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 8). Populations may have already peaked so that they are now slowly declining with more intensive management (see Conservation section). Surveys conducted by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) estimate that the population reached a peak of around 265,000 breeding pairs (+/- 25%) in the early 2000s, but it stabilized at an estimated 150,000 pairs over the last 10 years (Heusmann and Sauer 2000).

Figure 7: Canada Goose relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 8: Canada Goose population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Breeding resident Canada Geese are not a species of conservation concern in Virginia. They are often the target of management because the proliferation of resident geese has led to overgrazing of lawns and agricultural fields, accumulation of droppings in public areas, and aggressive behavior during nesting seasons. The VDWR and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Wildlife Services Division, employ various management strategies, including special resident goose hunting seasons and depredation orders that permit nest destruction, nonlethal harassment, and, when necessary, lethal control measures (Lowney et al. 1997).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Heusmann, H. W., and J. R. Sauer (2000). The northeast states’ breeding waterfowl population survey. Wildlife Society Bulletin 28:355–364.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Lowney, M., P. Eggborn, G.R. Costanzo, and D. Patterson (1997). Development of an integrated Canada goose management program in Virginia. Proceedings of the Eighth Eastern Wildlife Damage Management Conference 8:24–30.

Mowbray, T. B., C. R. Ely, J. S. Sedinger, and R. E. Trost (2020). Canada Goose (Branta canadensis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.cangoo.01.