Introduction

American Oystercatchers are a favorite species among birders visiting Virginia’s Eastern Shore. With their bright red bills and red-yellow eyes, it is hard to mistake this large shorebird for any other species. American Oystercatchers nest and forage on barrier islands, salt marshes, and other coastal areas where they can access mollusks, more specifically ribbed mussels (Geukensia demissa), a favorite food item among oystercatchers in Virginia (American Oystercatcher Working Group et al. 2020). The oldest known American Oystercatcher, aged 23 years and 10 months, was banded in Virginia in 1989 and recovered in Florida in 2012 (Cornell Lab of Ornithology 2019).

Breeding Distribution

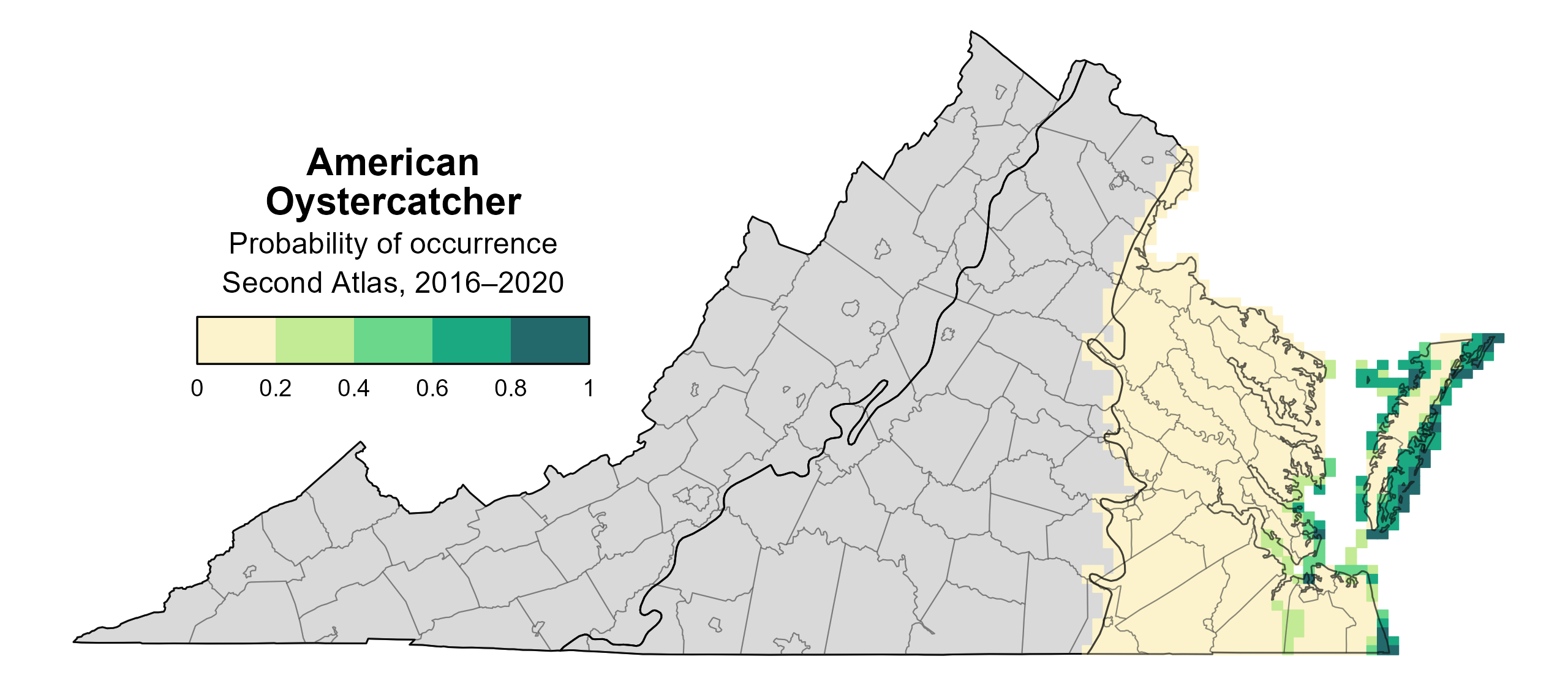

American Oystercatchers inhabit only the Coastal Plain region, where the species is most likely to occur in blocks on the Eastern Shore. However, they also occur in the coastal areas along the Middle and Lower Peninsulas, Virginia Beach area, and Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge. On the Eastern Shore, they are most likely to occur along its margins (Figure 1).

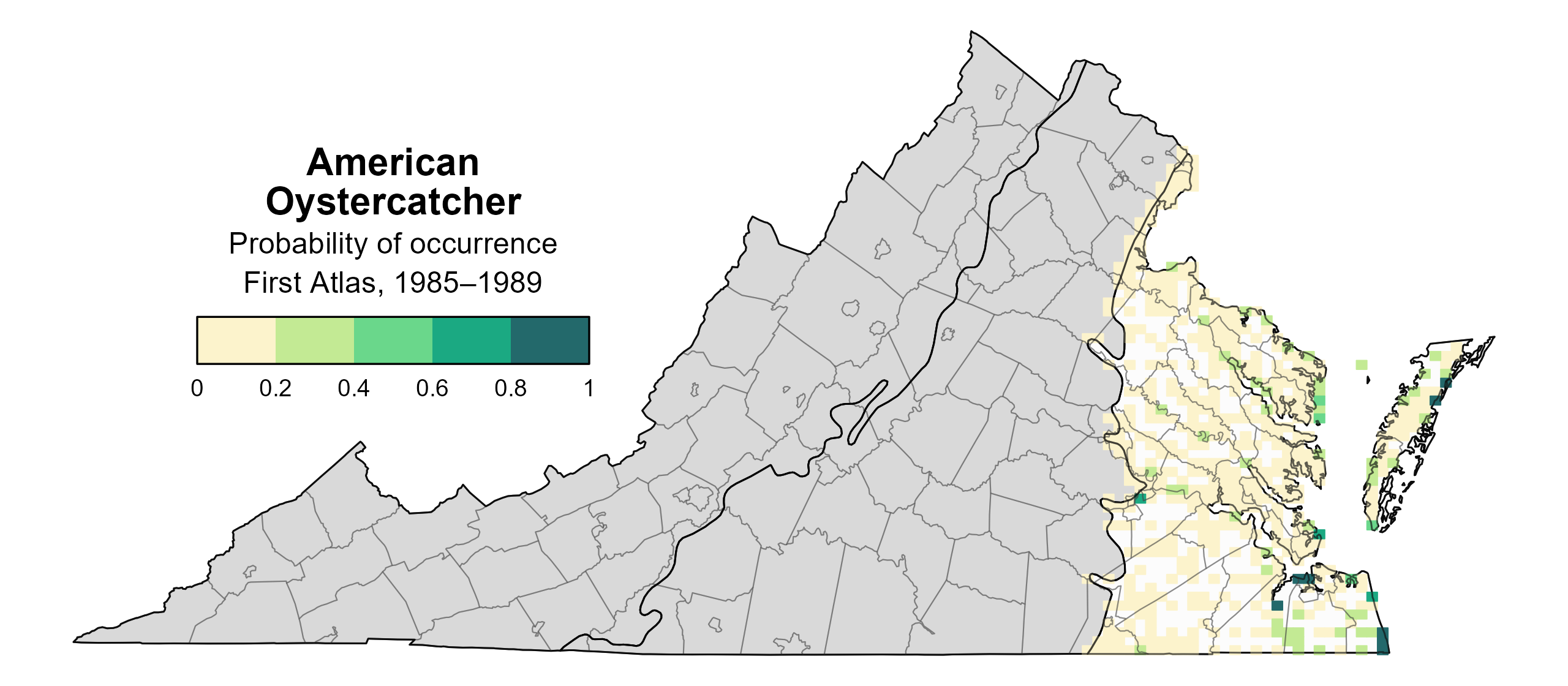

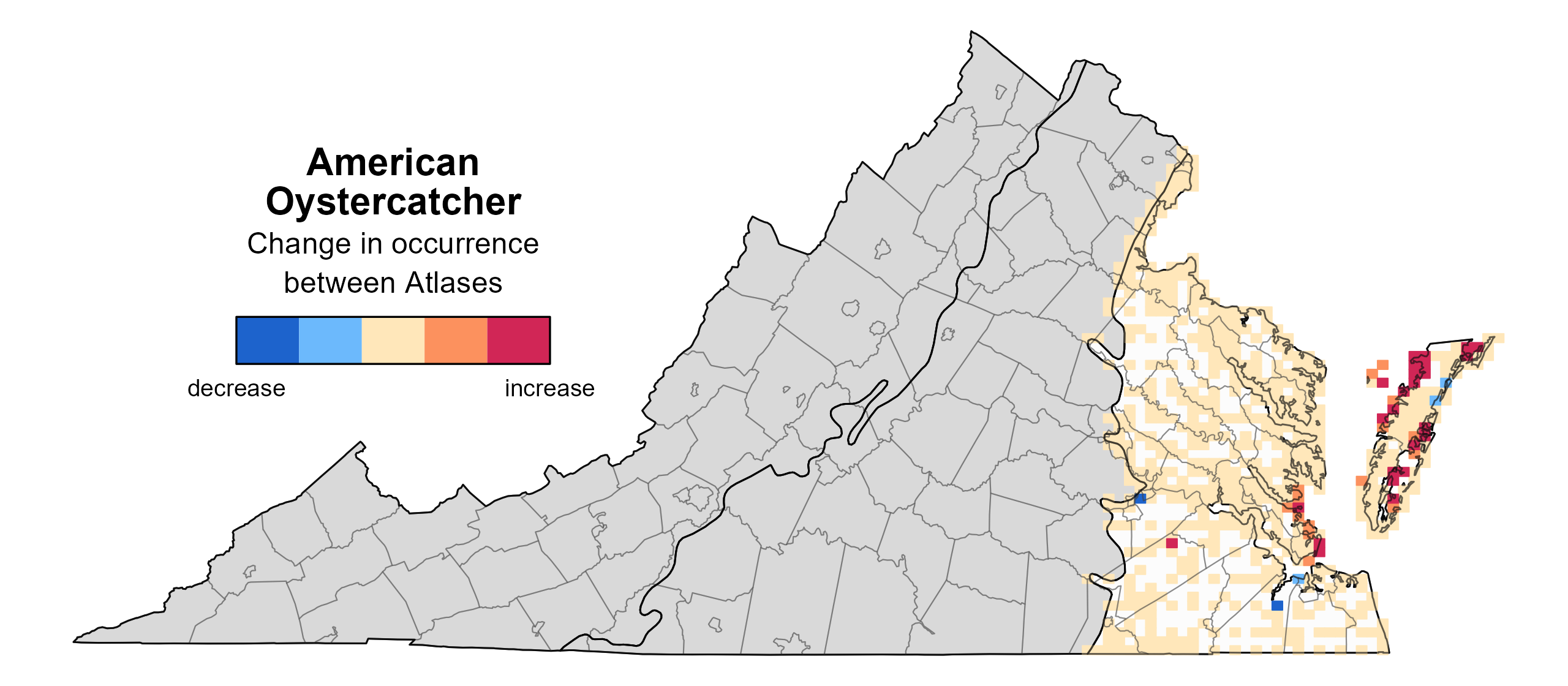

Between the First and Second Atlases (Figures 1 and 2), the American Oystercatcher’s probability of occurrence was predicted to remain constant throughout its range in the Coastal Plain region, except for a potential increase along the coastline of the Virginia Peninsula (Figure 3).

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: American Oystercatcher breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence Second Atlas (2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray lie outside the core range of the species.

Figure 2: American Oystercatcher breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray lie outside the core range of the species.

Figure 3: American Oystercatcher change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray lie outside the modeled region of the species.

Breeding Evidence

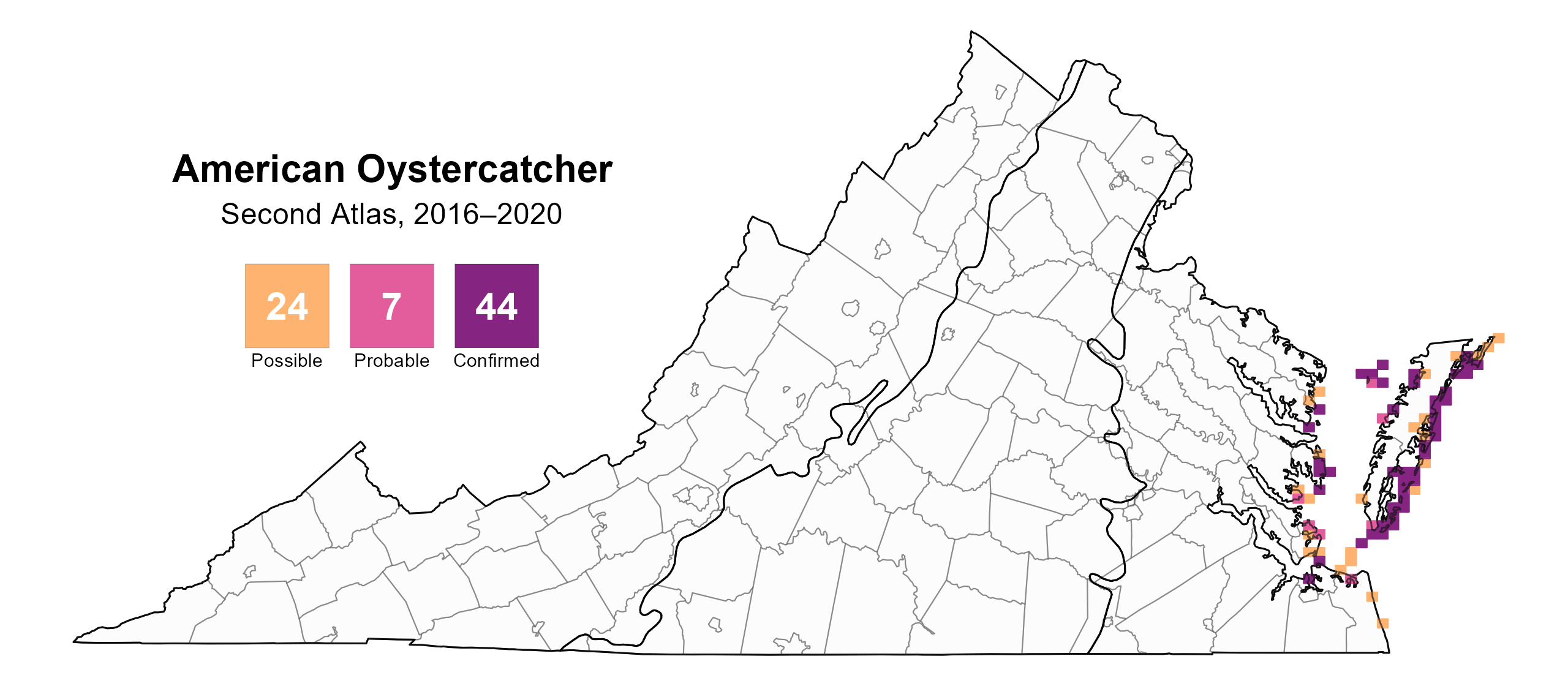

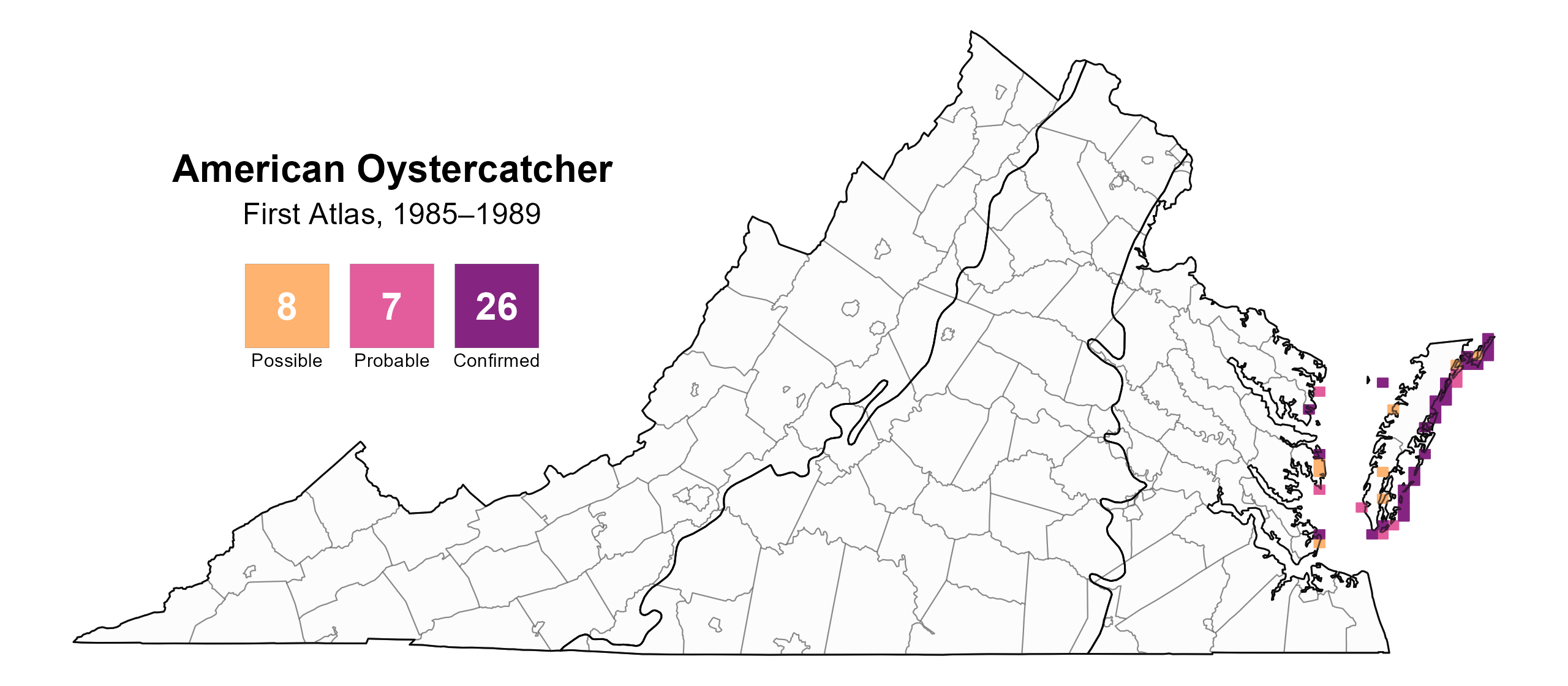

American Oystercatchers were confirmed breeders in 44 blocks, five counties (Accomack, Lancaster, Mathews, Northampton, and Northumberland), and two cities (Hampton and Portsmouth) and found to be probable breeders in Gloucester County and the cities of Poquoson and Virginia Beach (Figure 4). Breeding observations were confined to similar areas during both Atlas periods (Figures 4 and 5).

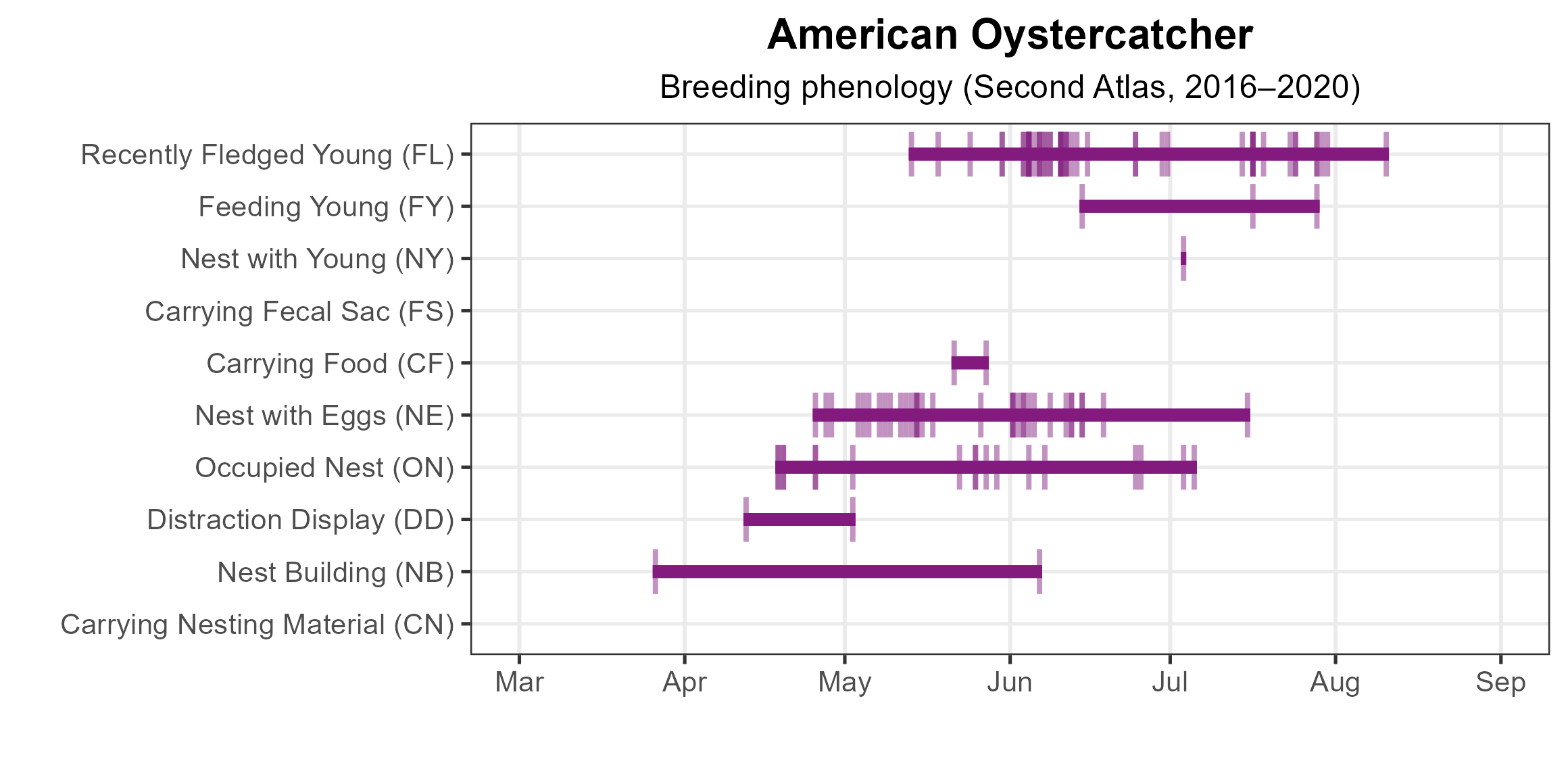

The earliest confirmed breeding behavior was nest building, which was recorded in mid-March. Most confirmations were based on observations of occupied nests (April 18–July 5), nests with eggs (April 25–July 15), and recently fledged young (May 13–August 10) (Figure 6).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: American Oystercatcher breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: American Oystercatcher breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: American Oystercatcher phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

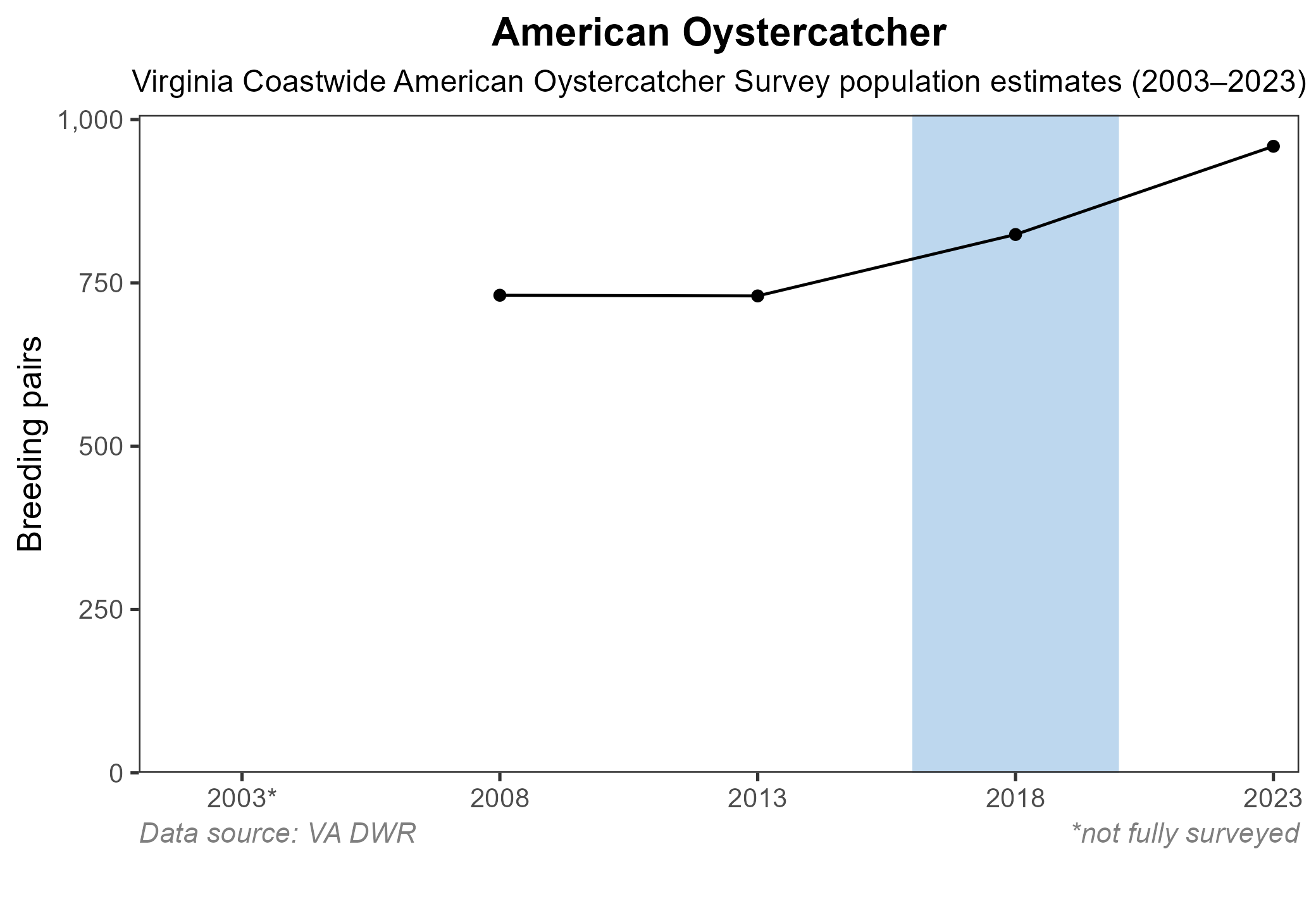

American Oystercatchers were not detected in sufficient number in point count surveys, so an abundance model could not be developed. This species is also not readily detected by the North American Breeding Bird Survey, which relies on roadside counts. However, based on the 2023 Virginia Coastwide American Oystercatcher Survey, 959 pairs were recorded during the breeding survey (Alex Wilke, TNC, unpublished data). The first such survey was conducted in 2003, with 588 pairs recorded. However, effort was well below that of subsequent surveys that were completed in 2008 and every five years since then. In 2008, a coastwide baseline of 731 pairs was obtained; as such, the 2023 pair estimate reflects a 31% increase in the breeding population over the past 15 years.

Figure 7: American Oystercatcher population trend for Virginia’s Coastal Plain. This chart illustrates the number of breeding pairs as estimated by Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources surveys. The shaded bar indicates the Second Atlas period.

Conservation

Wilke et al. (2005) documented that Virginia supports the largest breeding population along the Atlantic Coast, and this trend still holds true today. Eighty-seven percent of the nests are on protected lands that are managed to some degree for nesting shorebirds. However, in many areas, including Virginia, American Oystercatchers are considered a species of conservation concern because their reliance on coastal beach habitats means they are vulnerable to habitat loss and degradation from sea-level rise, increasing storm frequency and tidal inundation, and human development (American Oystercatcher Working Group et al. 2020). As such, the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan includes them as a Tier III Species of Greatest Conservation Need, indicating that they are of high conservation need (VDWR 2025).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Cornell Lab of Ornithology (2019). American Oystercatcher Overview. All About Birds.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Wilke, A. L., B. D. Watts, B. R. Truitt, and R. Boettcher (2005). Breeding season status of the American Oystercatcher in Virginia, USA. Waterbirds 28:308-315.

American Oystercatcher Working Group, E. Nol, and R. C. Humphrey (2020). American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.ameoys.01.