Introduction

A long-distance migrant emblematic of eastern deciduous forests, the Scarlet Tanager is striking in appearance and is present throughout the state. The males rank among the most vibrant birds in Virginia, with shocking red contrasting with jet-black wings, far more vibrant than the Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis), and yet, this species remains unknown to most Virginians. Preferring the treetops, they can be hard to locate despite their bright appearance. Ornithological awareness allows the keen observer to pick out their chick-burr call and hoarse, warbling song, delivered by both males and females.

Scarlet Tanagers occur in all types of deciduous forests, with a particular preference for mature, dry oak forests, although they will frequent wetter forests in the eastern portion of their range in the state, where hardwoods are replaced by pinewoods or agricultural fields in upland areas (Nicholas Flanders, personal communication). They are considered area-sensitive, and research has shown they need approximately 25 to 30 acres (10 to 12 hectares) of continuous forest to maintain populations (Mowbray 2020).

Breeding Distribution

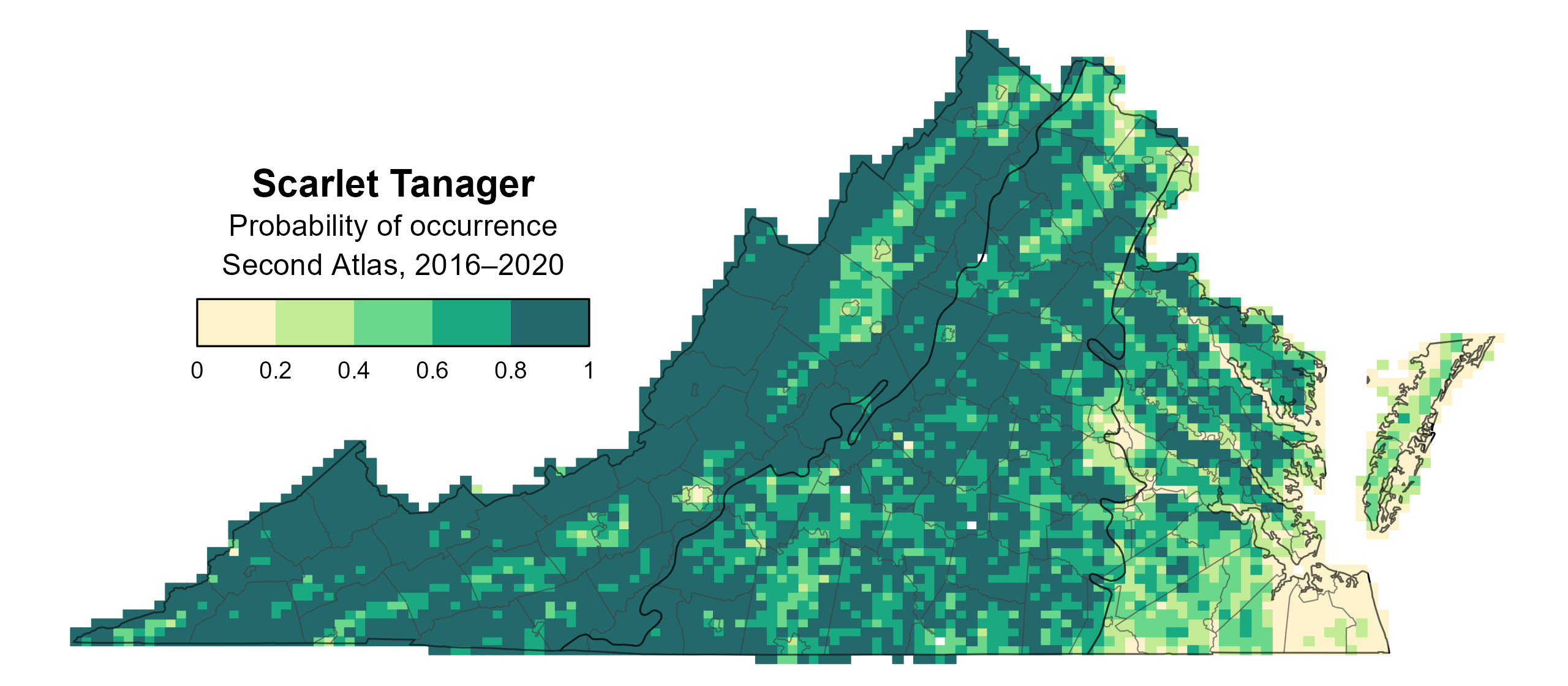

Scarlet Tanagers occur in all regions of the state and are ubiquitous at elevation in the Mountains and Valleys region (Figure 1). They are less likely to occur in the unforested lowlands of the Shenandoah Valley, and although they occur throughout the Piedmont region, they become less common in the southern portions. They are also unlikely in the immediate surroundings of Richmond and Washington, D.C. Scarlet Tanagers are also uncommon in the southern Coastal Plain region and on the Eastern Shore. These areas are generally considered the limits of the Scarlet Tanager’s range, which does not include most of the outer southeastern Coastal Plain south of Virginia. Nonetheless, outside of the southern Coastal Plain and Eastern Shore, their likelihood of occurring in a block is generally above 60%.

Scarlet Tanagers are more likely to occur in blocks with a greater amount of forest cover and larger forest patch sizes and are also slightly positively associated with agricultural lands. They are less likely to occur in blocks with grassland and shrubland habitats or those with a greater number of habitat types, which can be indicative of forest fragmentation and urbanization.

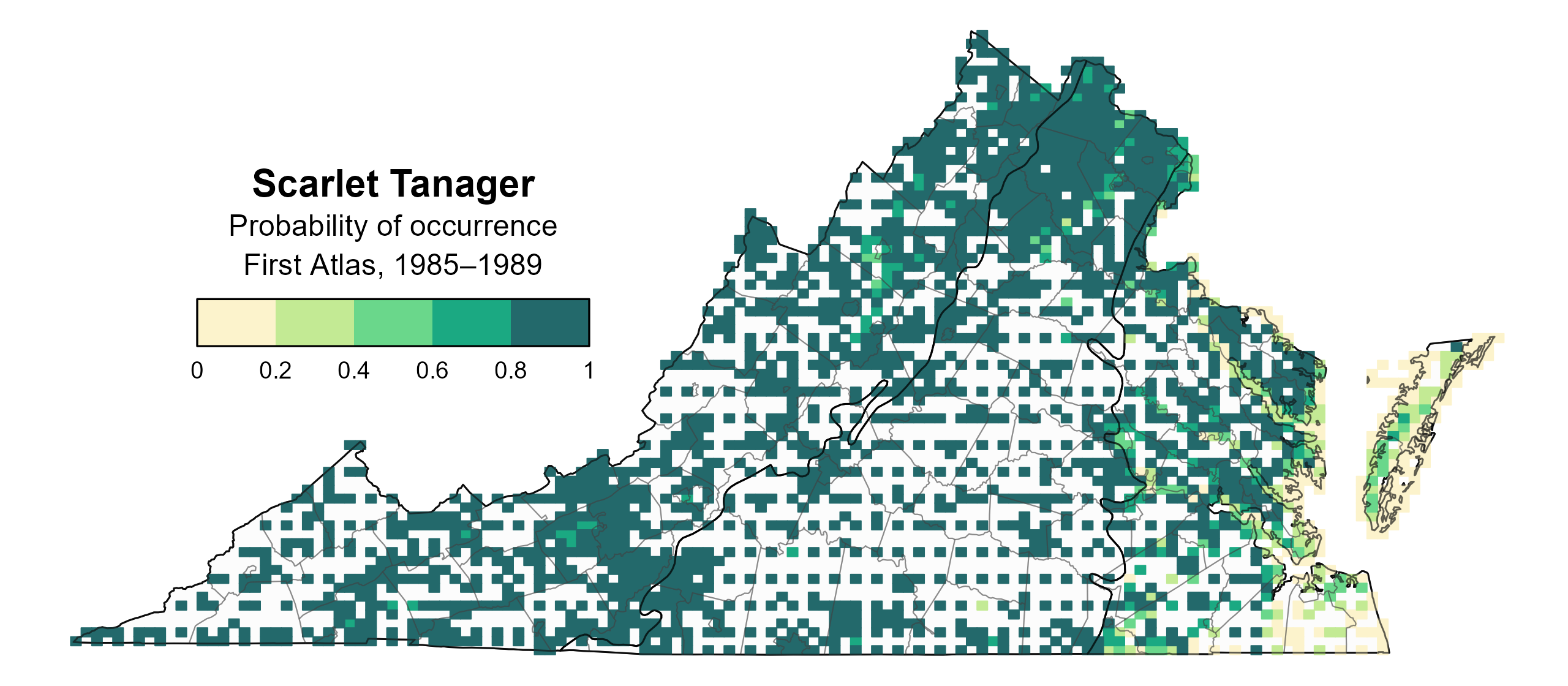

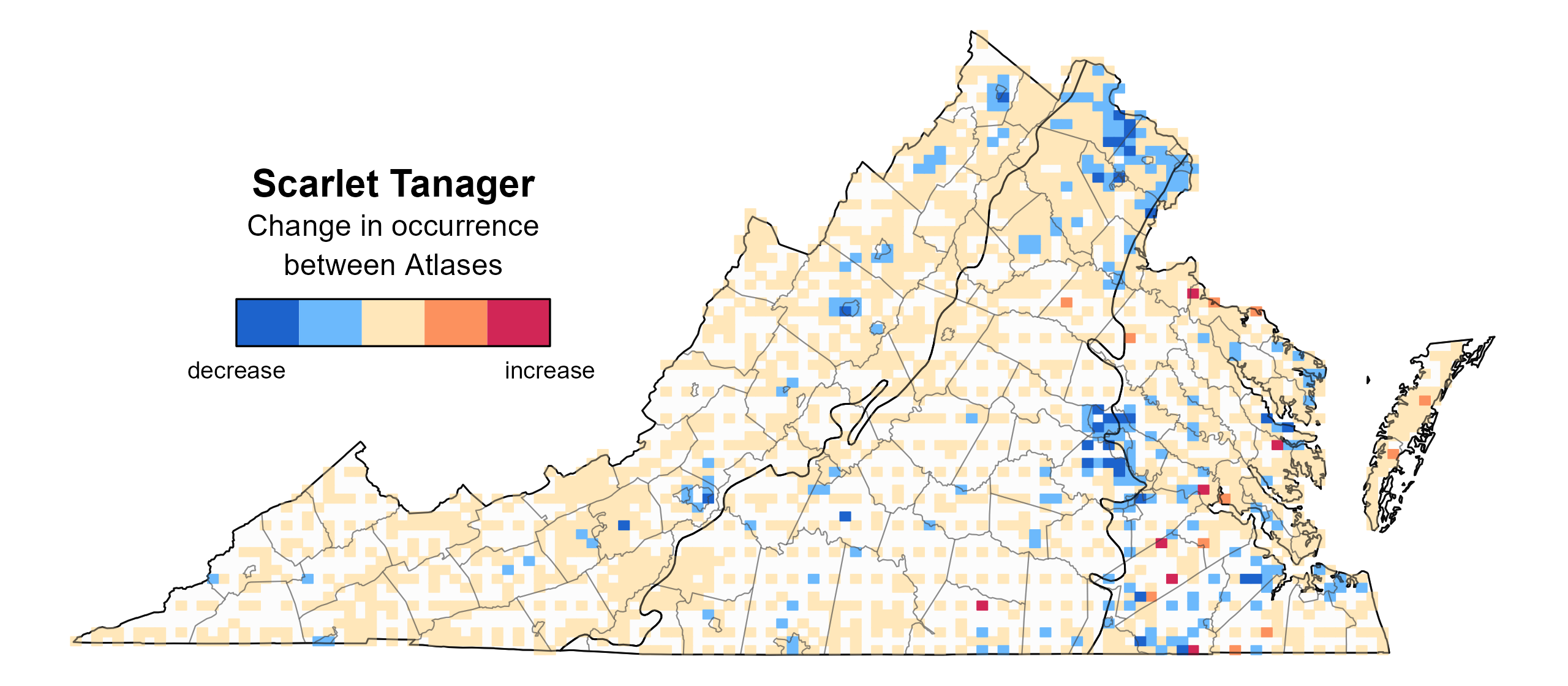

Scarlet Tanager probable occurrence in the Second Atlas was largely similar to that in the First Atlas (Figures 1 and 2). However, its likelihood of occurring decreased in the urbanized areas in Northern Virginia and Richmond as well as in smaller urban areas in the Mountains and Valleys region (Figure 3). The history of its distribution has followed the changes to forests in Virginia. During the 1930s, Scarlet Tanagers were restricted to the Mountains and Valleys region and rare in the Piedmont (Freer 1933). Reforestation in the century since has allowed the species, and many others of the eastern woodlands, to return statewide.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Scarlet Tanager breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Scarlet Tanager breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Scarlet Tanager change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

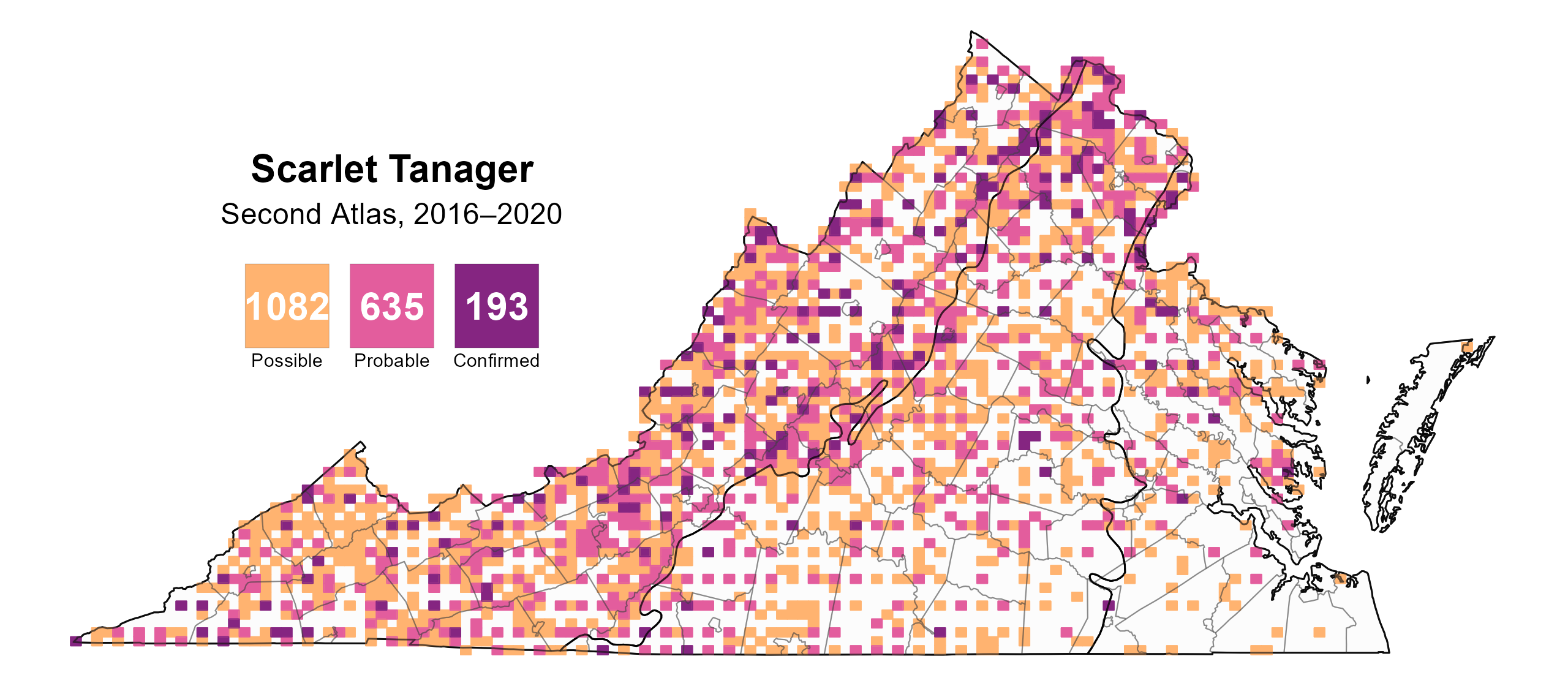

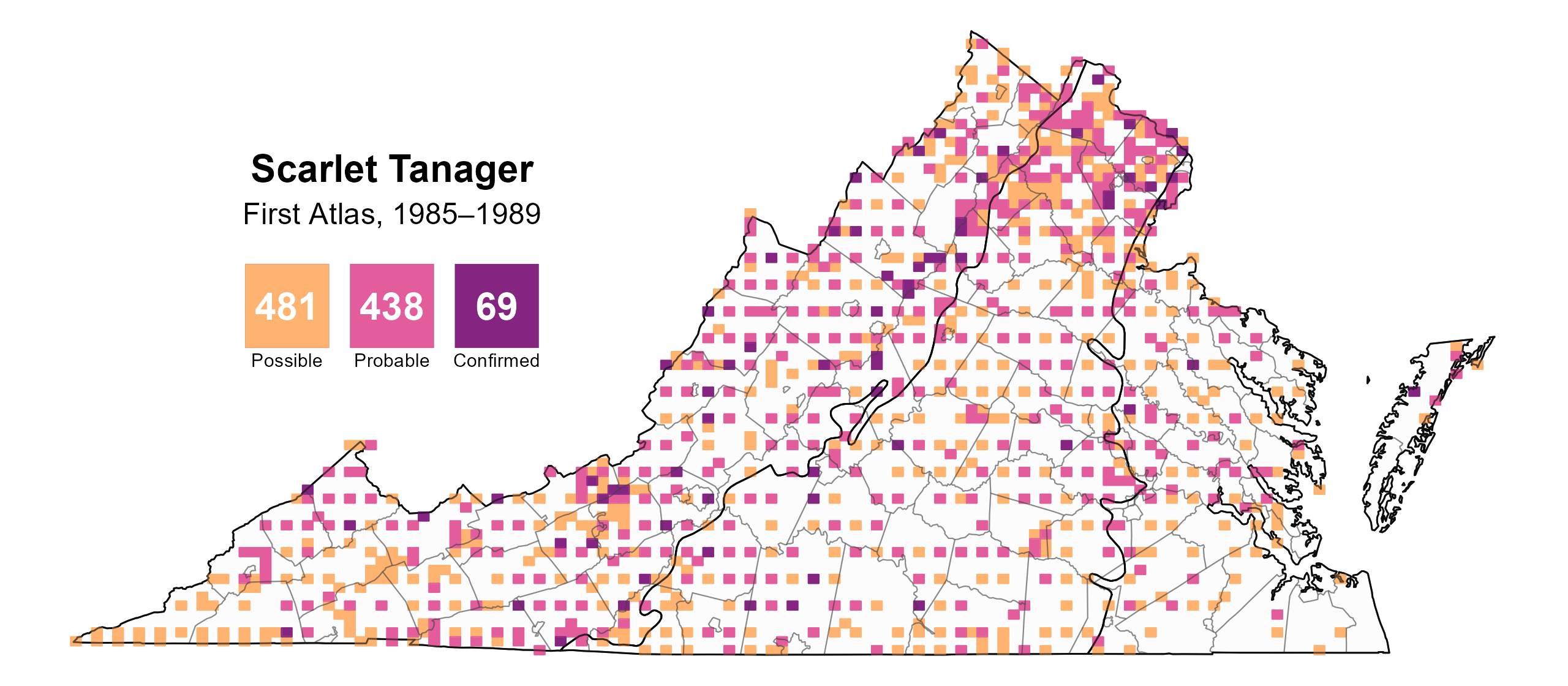

Scarlet Tanagers were confirmed breeders in 193 blocks and 58 counties and probable breeders in an additional 42 counties (Figure 4). However, breeding confirmations were much less frequent in the Coastal Plain region, and no breeding was confirmed on the Eastern Shore. Most breeding confirmations occurred in forested areas of the Piedmont and Mountains and Valleys region, but the species was considered a probable or possible breeder throughout the state. During the First Atlas, recorded breeding observations followed a similar pattern (Figure 5).

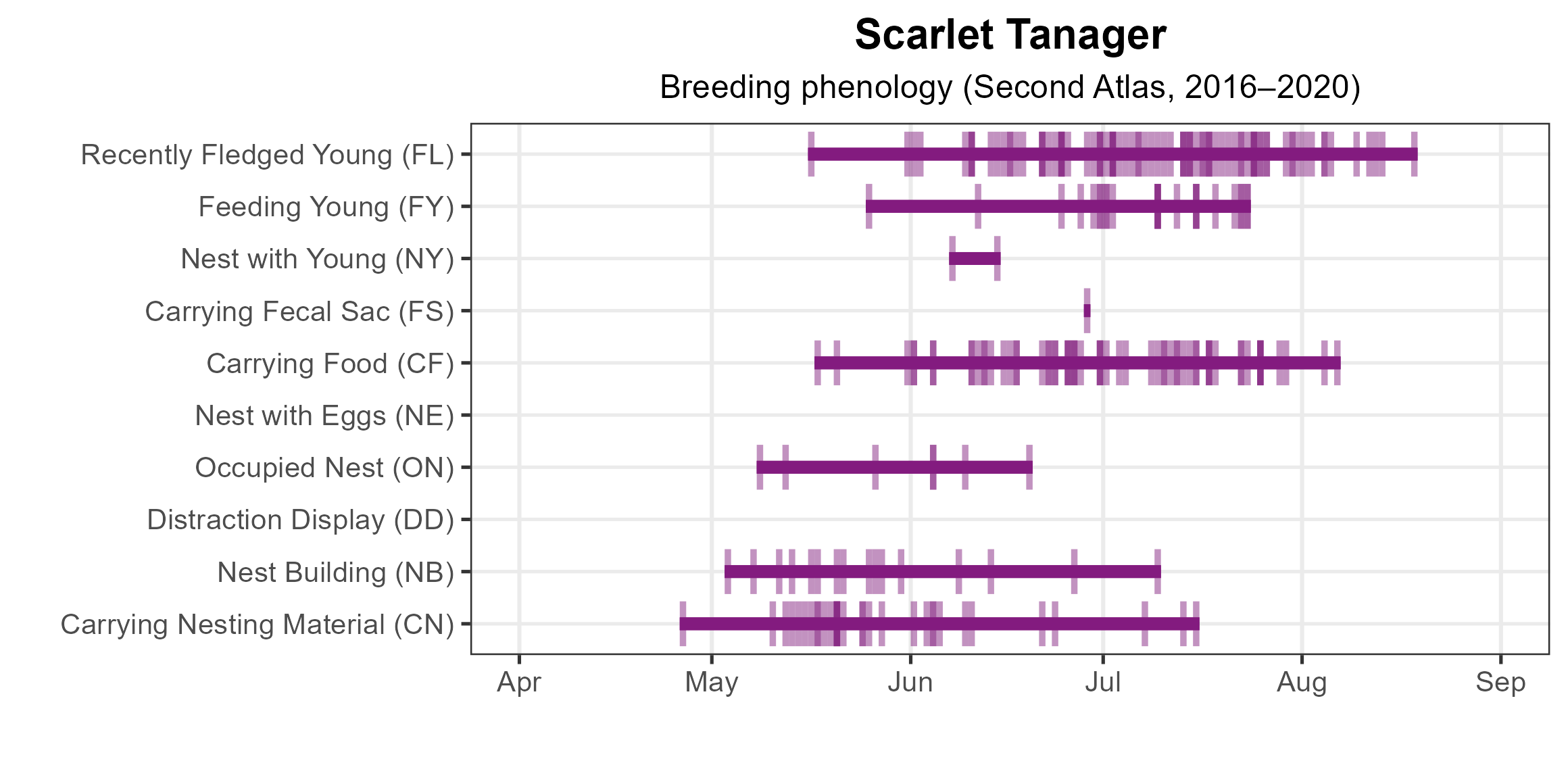

Adults carrying nesting material was the earliest recorded breeding behavior on April 26. Fledgling care continued through August 18 (Figure 6). Most breeding confirmations came from observations of recently fledged young and adults carrying food. Nesting typically occurs high in the canopy, often at heights exceeding 20 ft (6 m) (Mowbray 2020), which can make observing nests challenging. There were seven observations of occupied nests and only two of nests with young. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Scarlet Tanager, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Scarlet Tanager breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Scarlet Tanager breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Scarlet Tanager phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Scarlet Tanager relative abundance was estimated to be highest in the Mountains and Valleys region, particularly in the extensively forested areas (Figure 7). Abundances levels were more moderate throughout the Piedmont region and lowest in the Coastal Plain region.

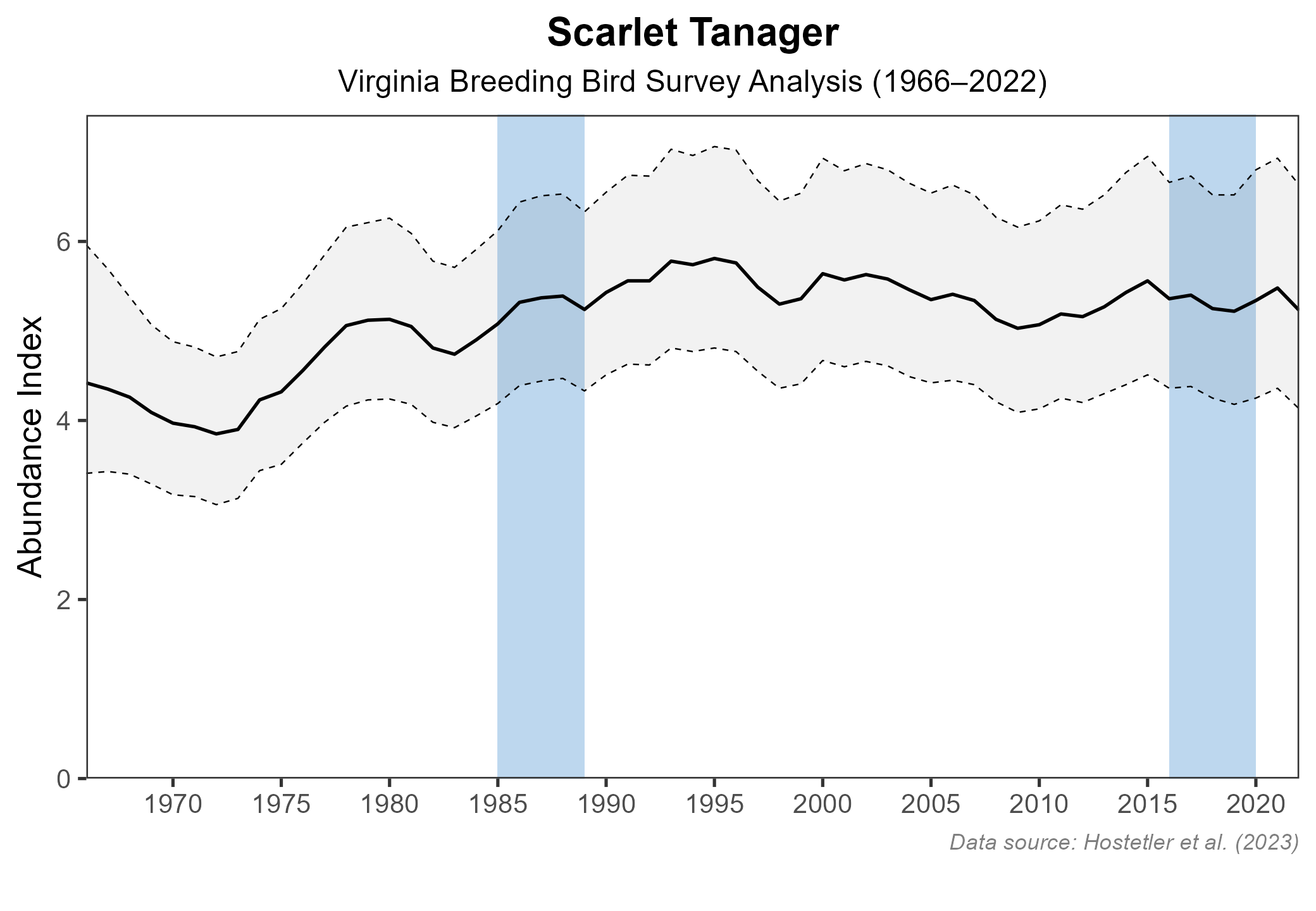

The total estimated Scarlet Tanager population in the state is approximately 501,000 individuals (with a range between 394,000 and 639,000). Scarlet Tanager populations are apparently stable in Virginia. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) showed a nonsignificant increase of 0.3% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 8). Between the Atlases, BBS data showed a similar nonsignificant decline of 0.07% per year in Virginia from 1987–2018. Local changes in their populations caused by habitat change are offset by an overall robust population. However, BBS data may over-represent unpaired males in roadside forest patches too small to maintain populations (Mowbray 2020).

Figure 7: Scarlet Tanager relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 8: Scarlet Tanager population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Scarlet Tanager populations in Virginia are stable and widespread, and the species is not considered a conservation concern. This scenario contrasts with that of many other long-distance migrants, which have shown population declines in recent decades. Nonetheless, continued habitat protection, particularly of large, contiguous forests, is important for maintaining healthy populations.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Freer, R. S. (1933). Summer records from the Virginia Piedmont. The Auk 50:448.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Mowbray, T. B. (2020). Scarlet Tanager (Piranga olivacea), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.scatan.01.