Introduction

Bright yellow below and olive above with a black mask, the Kentucky Warbler is a highly vocal warbler of southern forests. Across its range, it sings its rolling churree from moist forests with well-developed understories, including bottomland forests and upland deciduous forests near streams (McDonald 2020). It has also been known to favor cove hardwood forests in certain areas of western Virginia (McShea et al. 1995). The Kentucky Warbler nests on the forest floor and searches the leaf litter for spiders, ants, beetles, and other arthropods.

Breeding Distribution

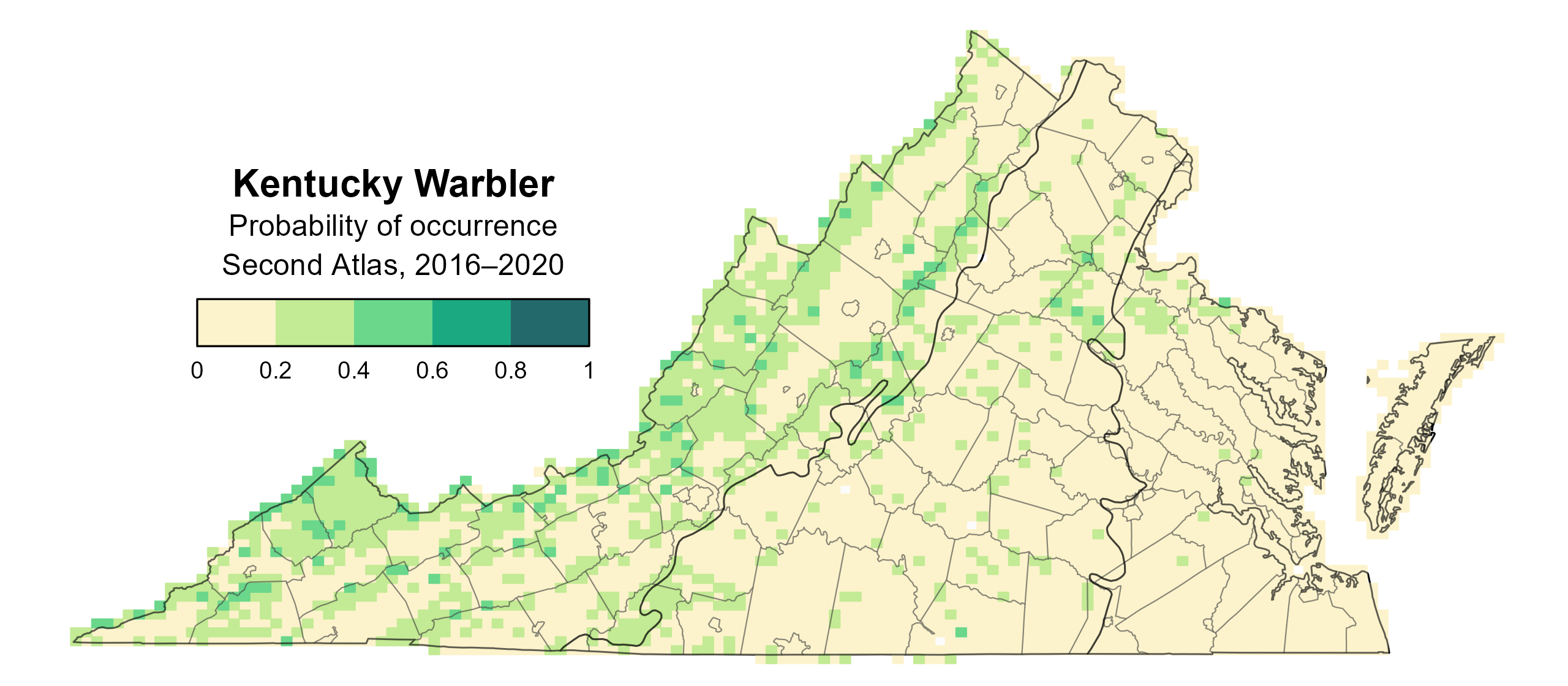

The Kentucky Warbler is found throughout Virginia, although its distribution is patchy, and its likelihood of occurrence is relatively low across regions. It is most likely to be found in forested areas in the Mountains and Valleys region and least likely to occur in the Coastal Plain region (Figure 1). The species has a positive association with percent forest cover and mean annual rainfall in a block, underscoring its preference for damp forests.

Between the First and Second Atlases (Figures 1 and 2), the likelihood of finding Kentucky Warblers decreased substantially across much of the state, especially in the northern Piedmont and south-central Mountains and Valleys regions (Figure 3). This pattern may be connected to increasing urbanization in the northern Virginia area but is more difficult to explain in areas of the state where significant forest cover remains. There, it may be tied to changes in forest structure and condition or impacts occurring outside the breeding season.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Kentucky Warbler breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Kentucky Warbler breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Kentucky Warbler change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

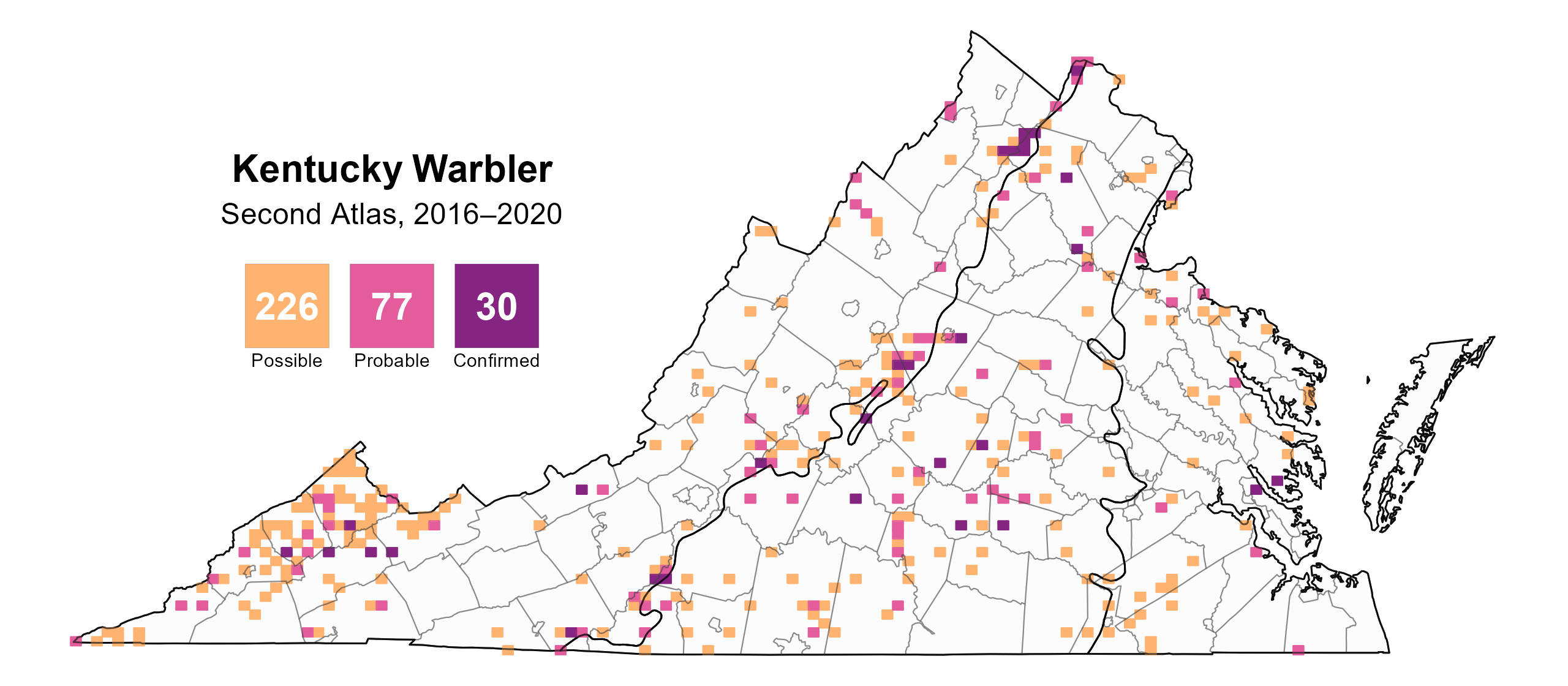

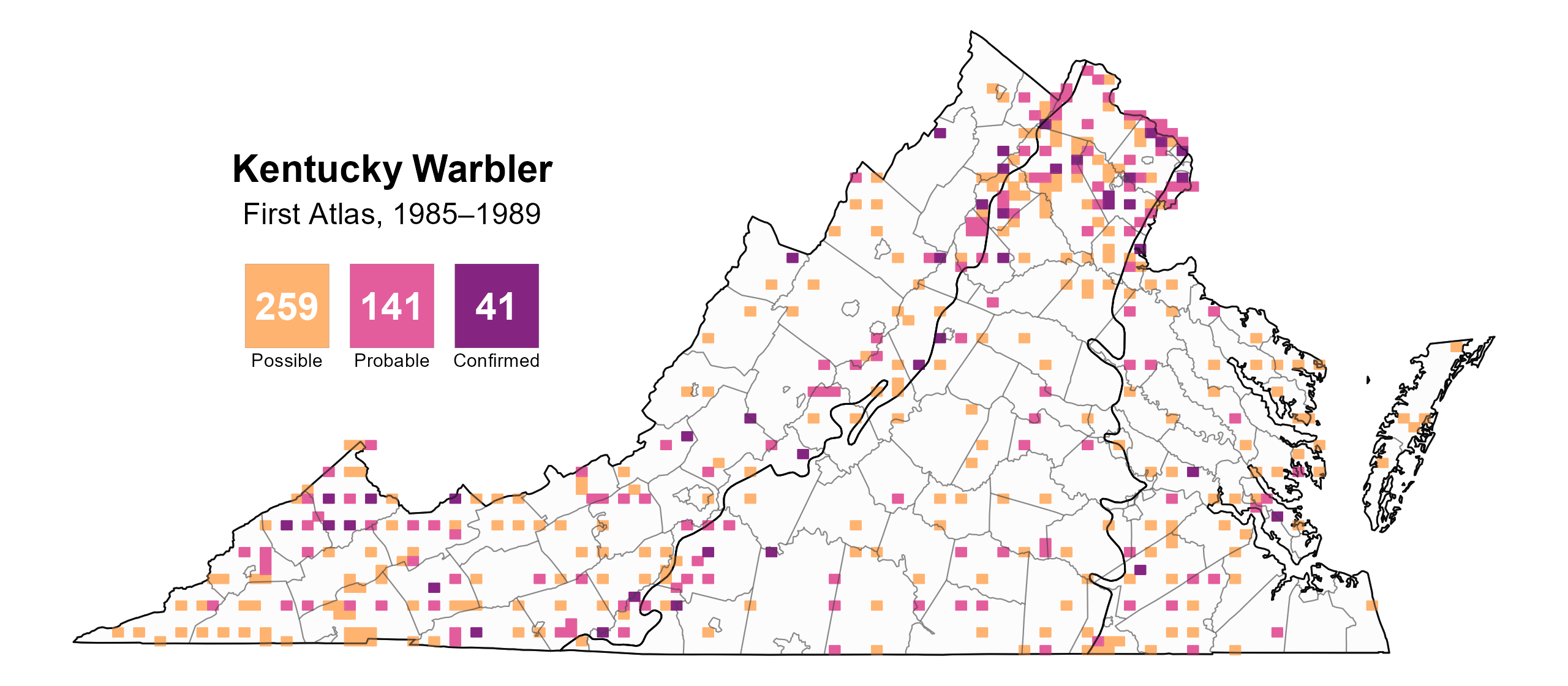

Kentucky Warblers were confirmed breeders in 30 blocks and 22 counties and found to be probable breeders in an additional 28 counties (Figure 4). The species was detected in 25% more blocks during the First Atlas than during the Second Atlas (Figure 5), despite lower survey effort. This result is consistent with the decrease in its likelihood of occurrence (Figure 3) and negative population trend during the period between Atlases (see Population Status section).

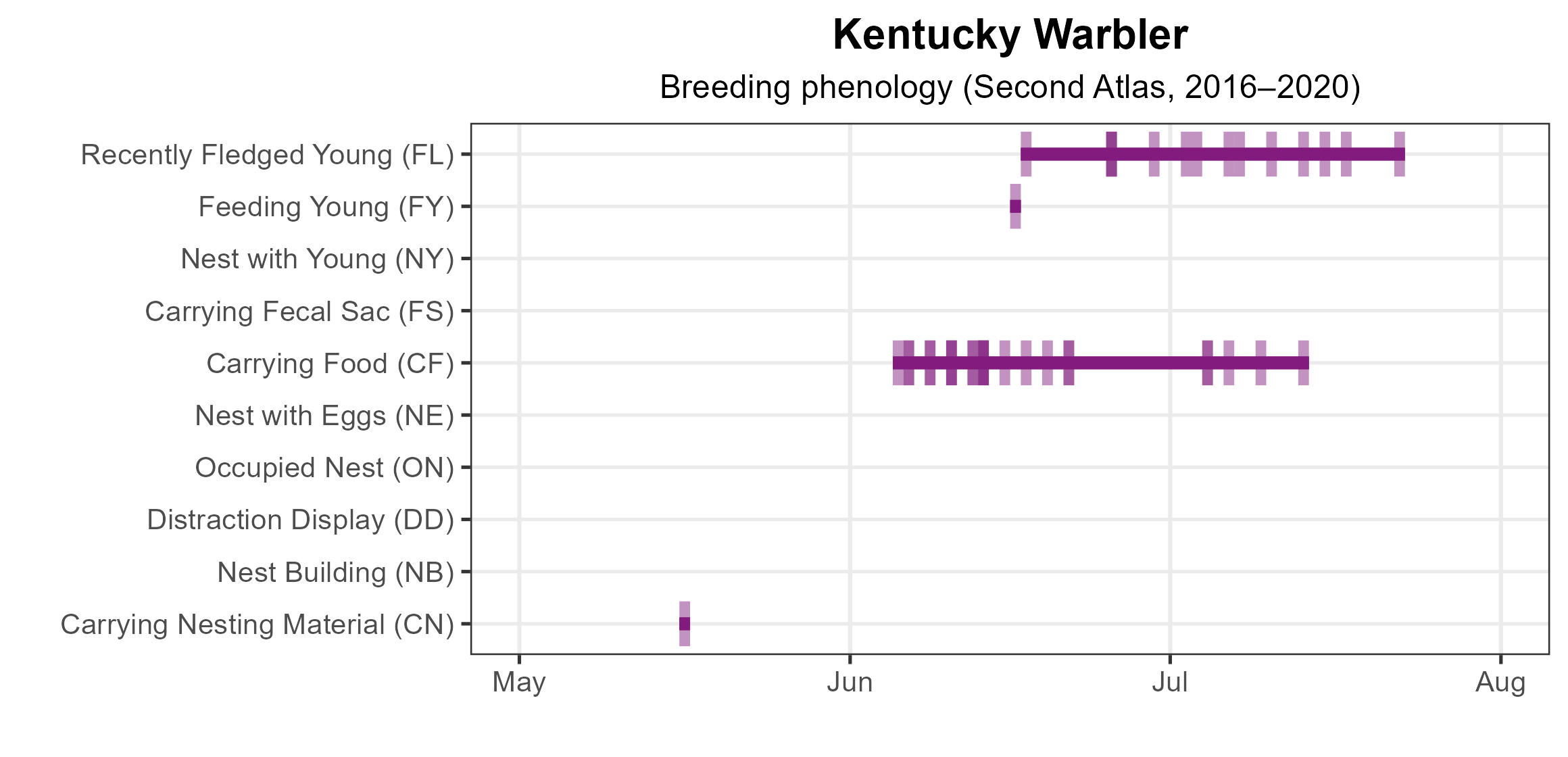

Kentucky Warblers build well-concealed nests on or very near the ground, making these difficult to find, and in fact, no nests were reported. The earliest confirmations of breeding consisted of adults carrying nesting material in early May. However, breeding was primarily confirmed by observations of adults carrying food (June 5 – July 13) and recently fledged young (June 17 – July 22) (Figure 6).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Kentucky Warbler breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Kentucky Warbler breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Kentucky Warbler phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

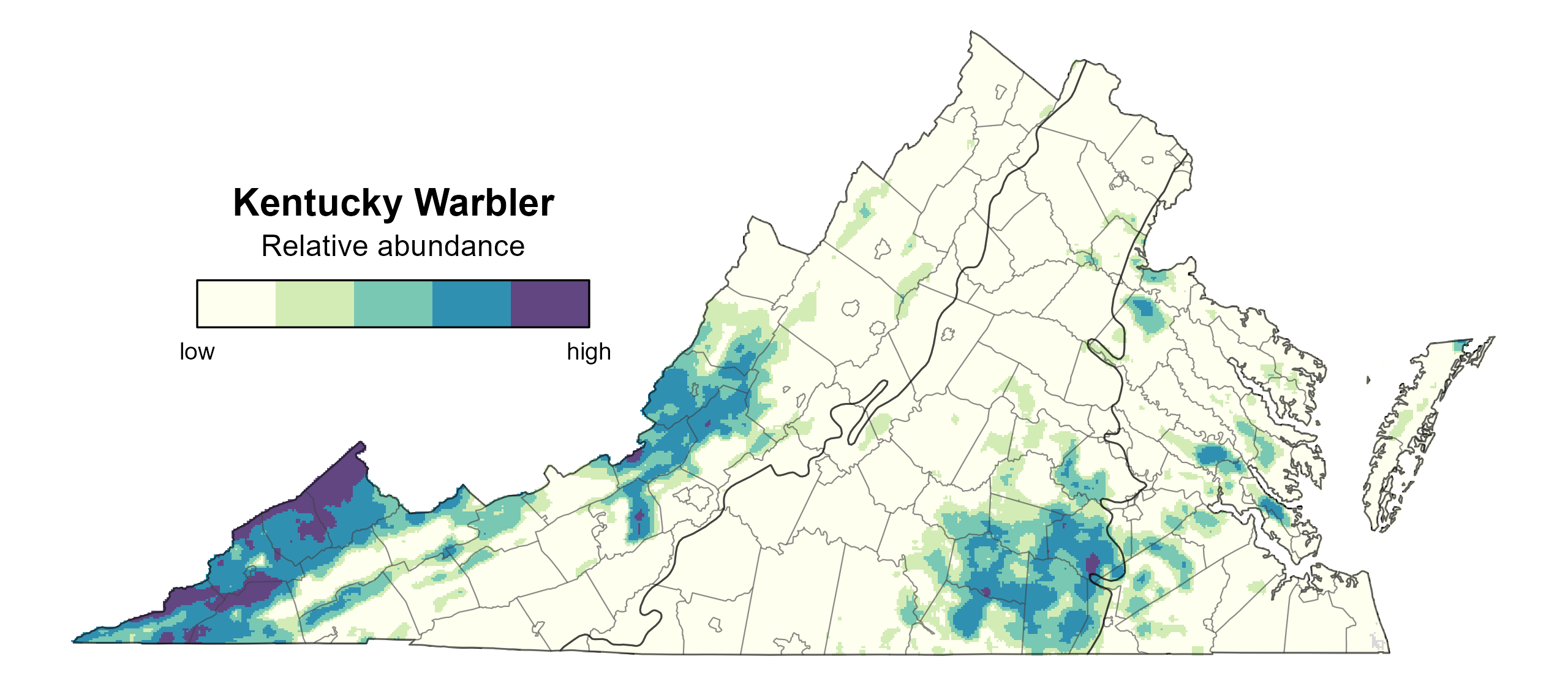

Within each region, there were specific areas estimated to have the highest relative abundance of the Kentucky Warbler. These areas include Fort Walker (Caroline County) and segments of the Lower Peninsula (New Kent and York Counties) in the Coastal Plain; a cluster of counties in the southeastern Piedmont, including portions of Brunswick, Dinwiddie, Lunenburg, and Mecklenburg; and an area concentrated within Alleghany, Botetourt, Craig, and Montgomery Counties, as well as multiple counties in extreme southwestern Virginia in the Mountains and Valleys region (Figure 7). The species’ overall relative abundance was estimated to be low in comparison to that of several other warbler species.

The total estimated Kentucky Warbler population in the state is 44,000 individuals (with a range between 29,000 and 68,000). Based on the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), the Kentucky Warbler’s population declined by a significant 2.64% annually from 1966–2022 in Virginia and by a significant 3.38% per year between Atlases (1987–2018) (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 8).

Figure 7: Kentucky Warbler relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 8: Kentucky Warbler population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Given the size of the Kentucky Warbler population and its decline in Virginia, the 2025 Wildlife Action Plan includes this species as a Tier III (High Conservation Need) Species of Greatest Conservation Need (VDWR 2025).

Kentucky Warblers depend on a dense understory for breeding. At a long-term study site in Warren County, the species benefited from localized disturbances such as tree falls and wind damage (McDonald 2020). Such disturbances open gaps in the canopy, contributing to understory growth. In the absence of natural disturbances, forest management can be used to promote a dense understory and ground cover. Developing state-level or regional Best Management Practices specific to Kentucky Warbler would go a long way toward properly managing its habitat. These practices should also investigate and address minimum breeding area requirements for this forest interior songbird (McDonald 2020). Such information is needed to better assess its vulnerability to forest fragmentation.

The reasons for the Kentucky Warbler’s declines are not completely understood. While management on its breeding grounds should be pursued, research should also focus on the species’ ecology and reproductive success. In addition, this long-distance migrant may be vulnerable to threats on its wintering grounds. The Kentucky Warbler winters over a broad geographic range that includes Central America, northern South America, and the Antilles. Threats to the species and broader land-use changes may vary among these geographies. It is therefore important to identify where within that range breeding birds from Virginia and neighboring states spend the winter. This would be best accomplished through a regional or range-wide tracking study. Virginia has successfully participated in such studies for species that include Golden-winged Warbler (Vermivora chrysoptera), Cerulean Warbler (Setophaga cerulea), and Swainson’s Warbler (Limnothlypis swainsonii). Habitat use and general ecology should also be investigated on the Kentucky Warbler’s wintering grounds.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

McDonald, M. V. (2020). Kentucky Warbler (Geothlypis formosa), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.kenwar.01.

Mcshea, W. J., M. V. McDonald, E. S. Morton, R. Meier, and J. H. Rappole. (1995). Long-term trends in habitat selection by Kentucky Warblers. The Auk 112:375-381.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.