Introduction

The insect-like tick-tick-buzzz emanating from a scenic hayfield is an iconic part of the soundscape of rural Virginia. Appropriately named for its inconspicuous call, the Grasshopper Sparrow seems in many ways barely like a bird at all. Individuals give weak, fluttering flights and prefer scurrying like mice between bare patches of earth amid tufts of grass. Their unassuming brown plumage conceals surprising points of yellow in the lores and wing. Grasshopper Sparrows are migratory, arriving in Virginia in mid-April and departing by the end of October (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). This species is a model for the plight and perseverance of grassland birds in Virginia. As an umbrella species for grassland conservation, its habitat needs have been studied extensively.

Breeding Distribution

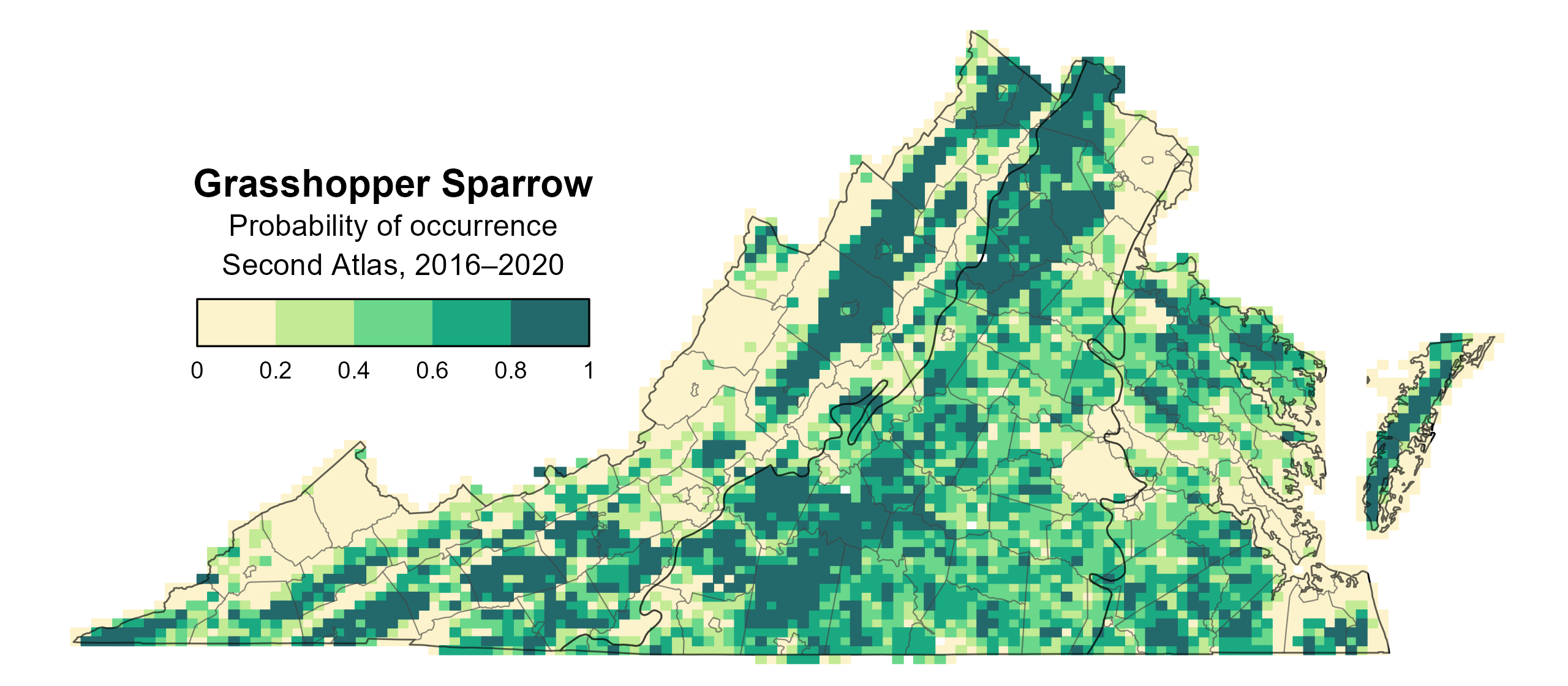

Grasshopper Sparrows occur in all regions of the state, but they are most likely to occur in the Shenandoah Valley and other agricultural areas in the Mountains and Valleys region, as well as in the eastern Piedmont region and on the Eastern Shore. They are less likely to be found in the forested highlands of the Allegheny and Blue Ridge Mountains or in urban areas of Northern Virginia and the I-64 corridor between Richmond and the Tidewater area (Figure 1).

The likelihood of Grasshopper Sparrow occurrence increases sharply with the proportion of agricultural lands (including hayfields and pastures) and grassland habitats in a block. They are also more likely to occur in blocks with a greater number of habitat types. Surprisingly, they also can occur in blocks with developed cover, such as residential areas or industrial complexes. Additionally, forests are a negative predictor of their occurrence as Grasshopper Sparrows are less likely to occur in blocks with larger forest patches or more forest edges.

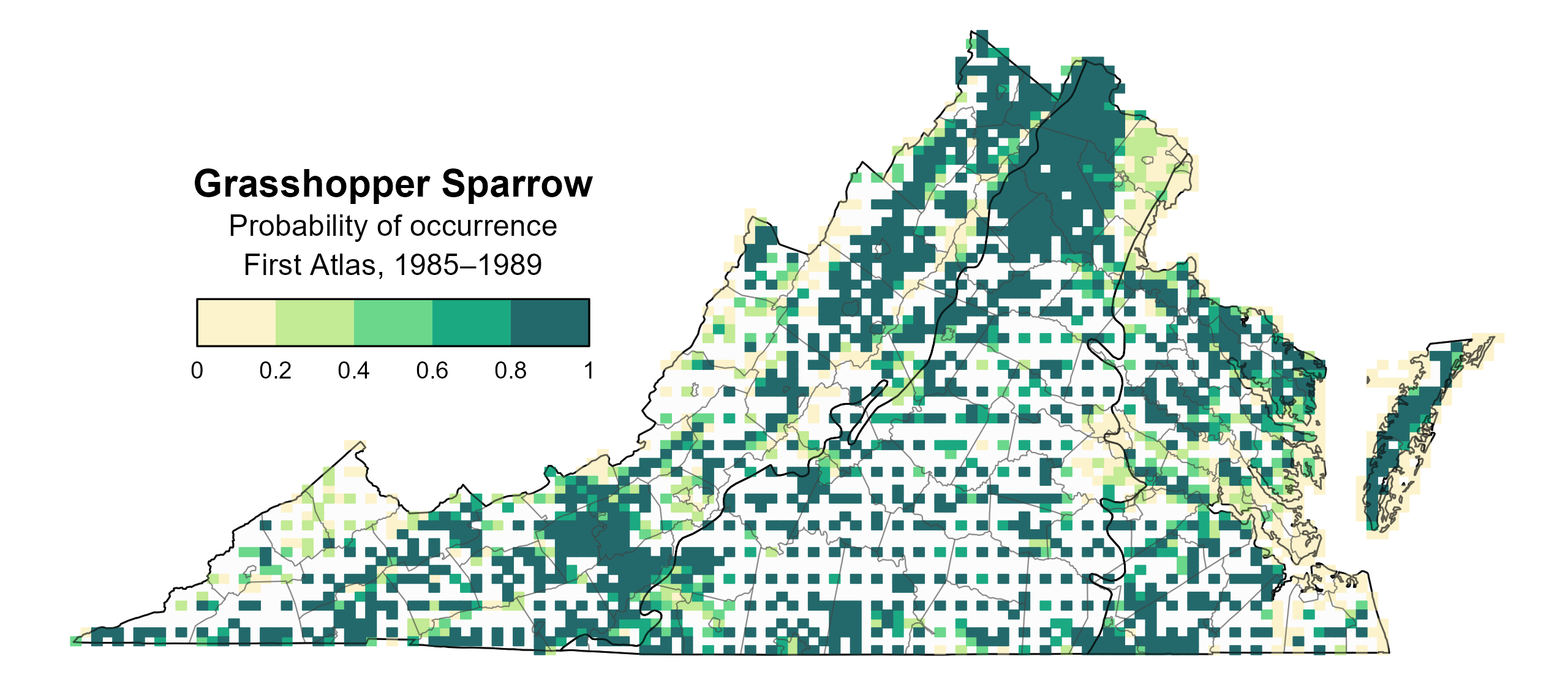

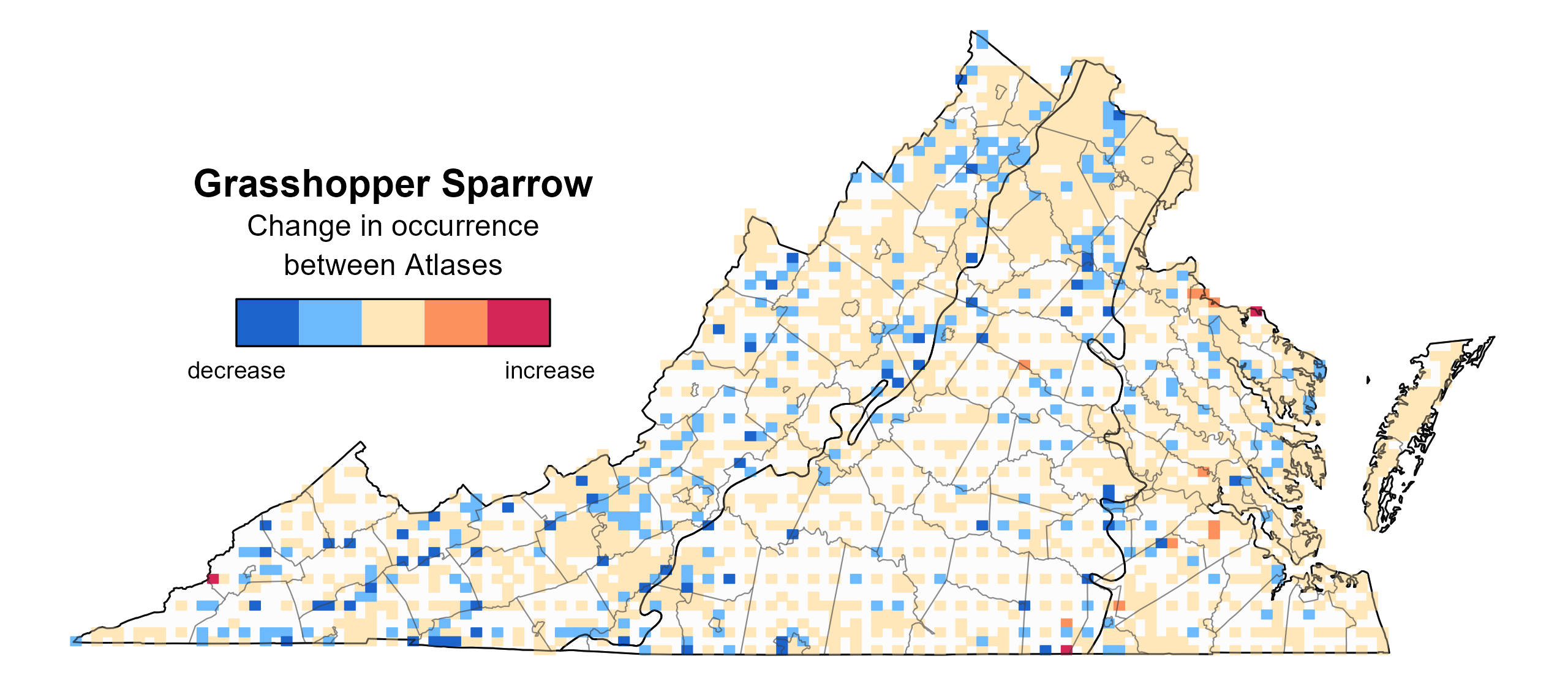

Between Atlases (Figures 1 and 2), Grasshopper Sparrow’s likelihood of occurrence decreased throughout much of the central and southern Mountains and Valleys region (Figure 3). These decreases are most prominent in areas of the state that have experienced a loss of agricultural landcover since the First Atlas. Its distribution was stable in the still-rural areas of the northern Piedmont and Shenandoah Valley, as well as throughout much of the Coastal Plain and on the Eastern Shore. As populations of Grasshopper Sparrows have declined (see Population Status), so too has the probability of encountering one.

Figure 1: Grasshopper Sparrow breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Grasshopper Sparrow breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Grasshopper Sparrow change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

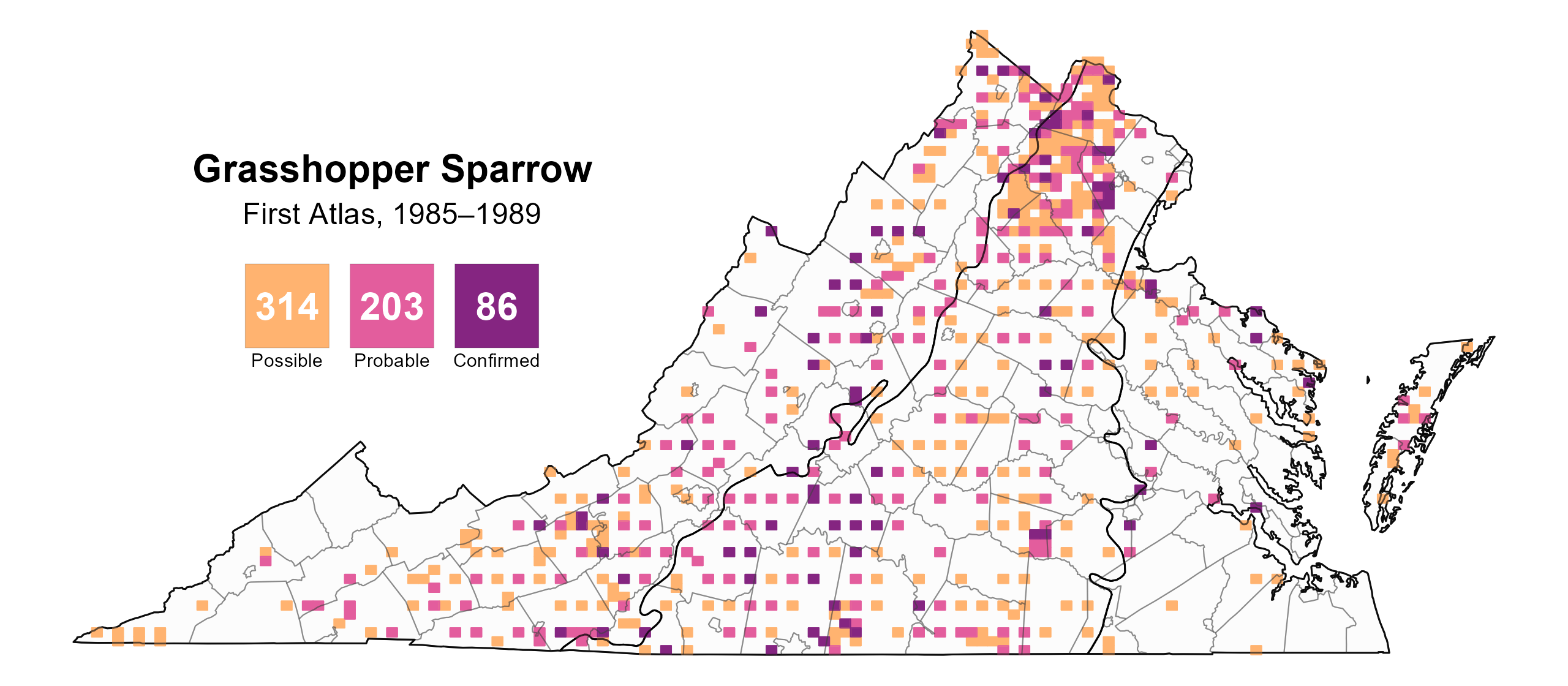

Grasshopper Sparrows were confirmed breeders in 156 blocks and 63 counties and probable breeders in another 29 counties (Figure 4). Breeding observations were concentrated in the Piedmont, on the Eastern Shore, and in the agricultural areas and valleys of the Mountains and Valleys region. During the First Atlas, breeding observations were recorded in similar areas of the state (Figure 5). Notably, fewer breeding observations were documented during the First Atlas, which is consistent with the species’ population decline in the state (see Population Status section); however, survey effort was less during the First Atlas, possibly contributing to the difference as well.

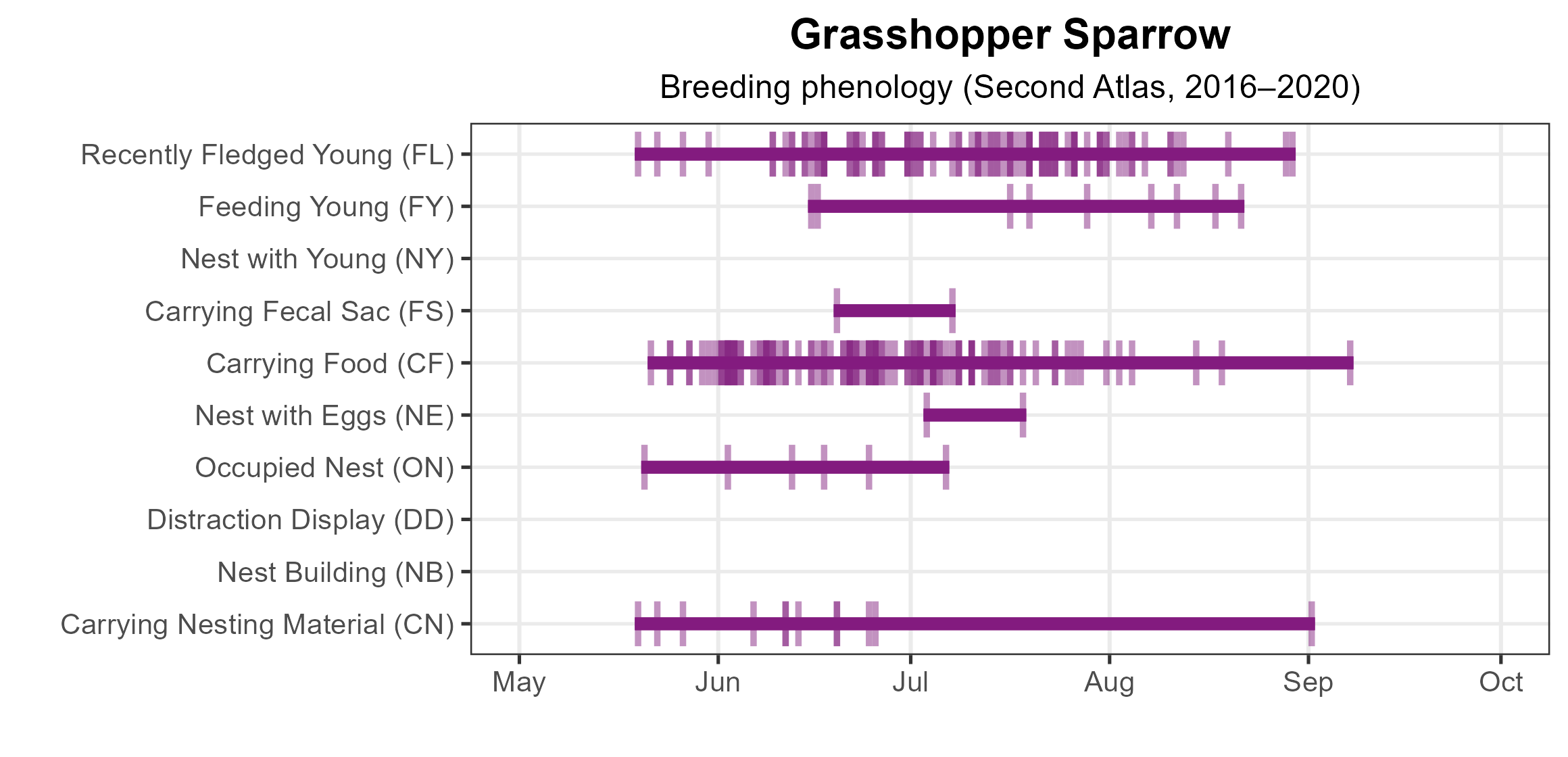

Grasshopper Sparrows commence breeding not long after their arrival in late April, as grass grows to suitable heights. Similar to many grassland birds, Grasshopper Sparrows nest on the ground, with secretive habits that make locating their nests challenging. Thus, most confirmations came from observations of adults carrying food (mid-May to mid-September) and sightings of recently fledged young (May 19 to the end of August), with very few nests found.

For more general information on the breeding habits of the Grasshopper Sparrow, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Grasshopper Sparrow breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Grasshopper Sparrow breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Grasshopper Sparrow phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

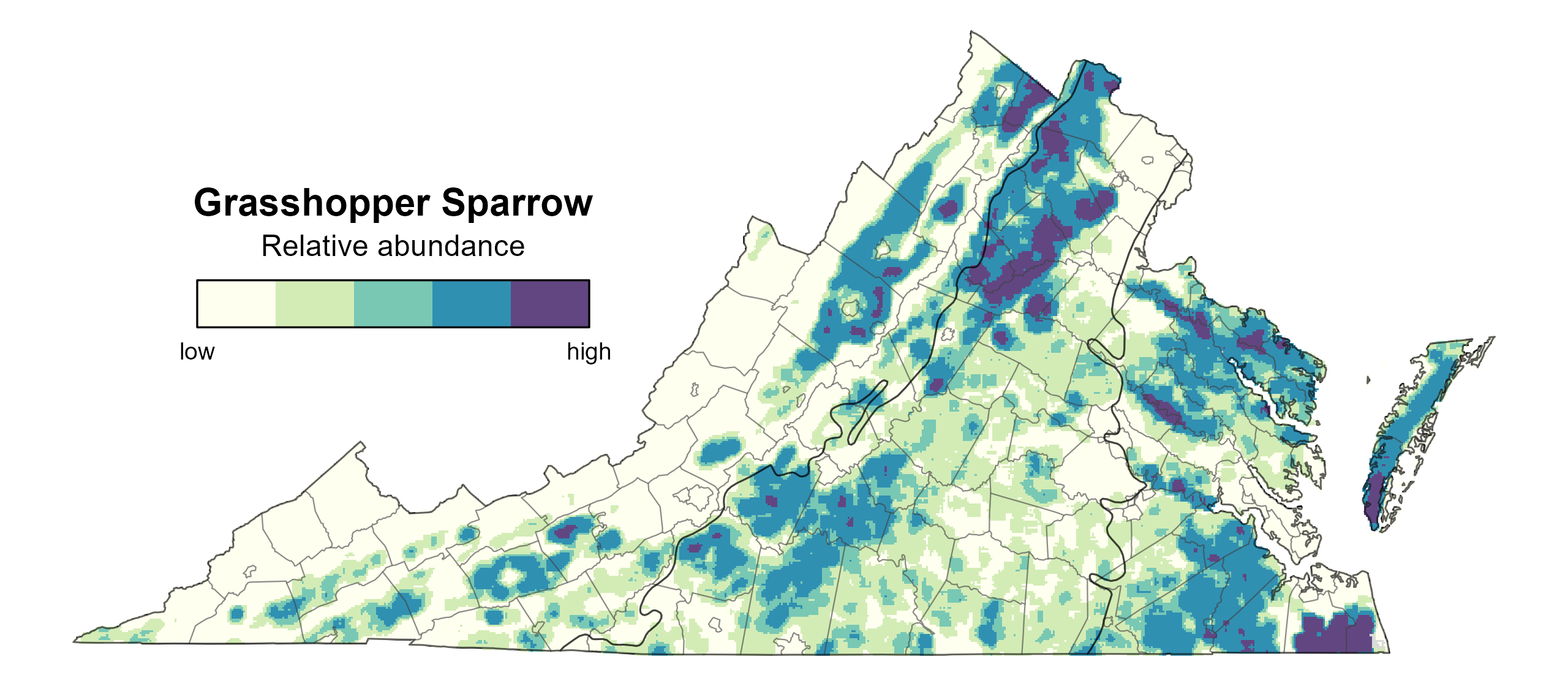

Grasshopper Sparrow relative abundance was estimated to be highest in the agricultural areas of the Shenandoah Valley, northern Piedmont region, and Eastern Shore (Figure 7). In the southern Piedmont region, abundance was generally higher closer to the Blue Ridge Mountains with a patchy distribution. Abundance was extremely low in developed areas in Northern Virginia, Richmond, and the Hampton Roads-Virginia Beach area.

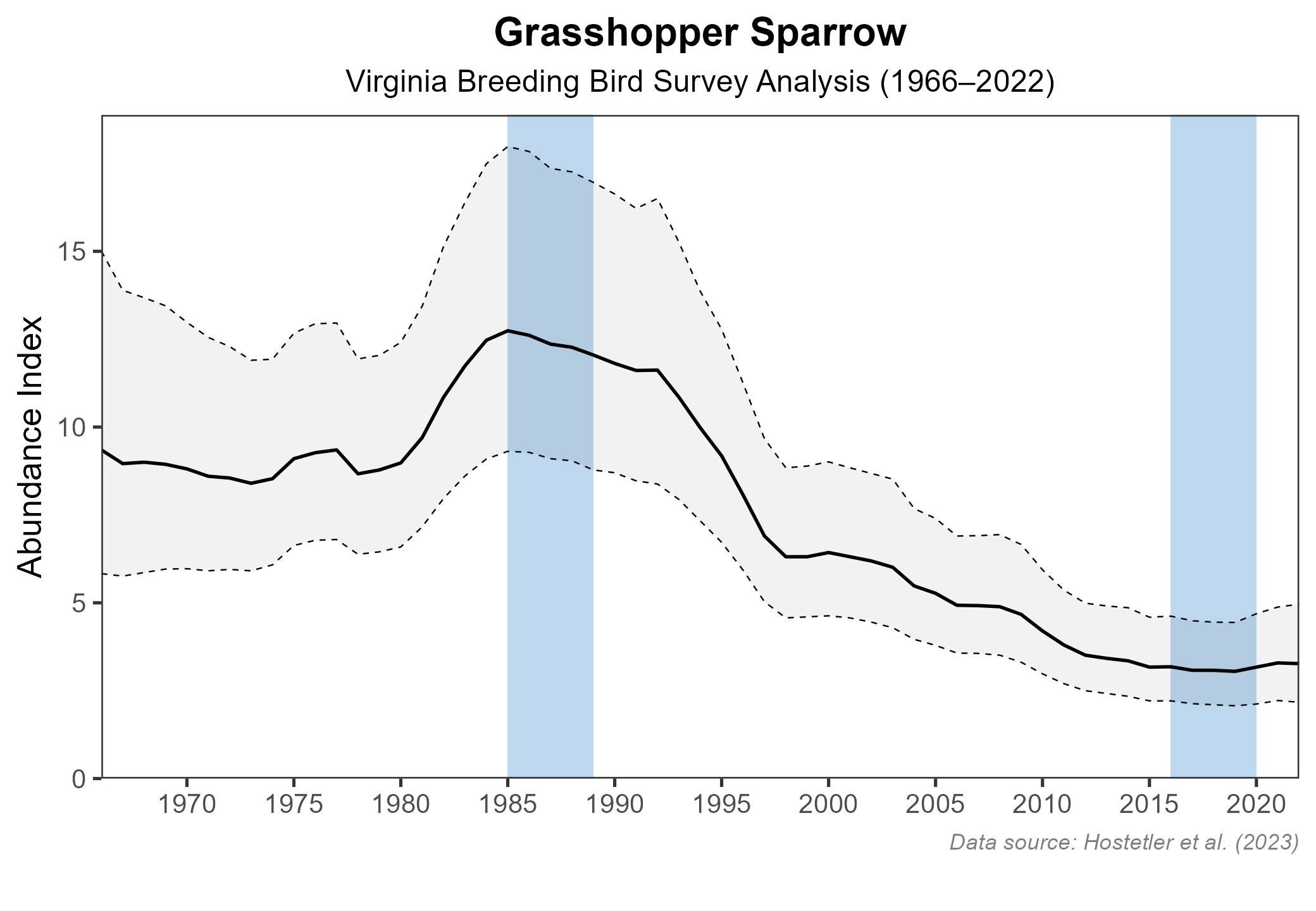

The total estimated Grasshopper Sparrow population in the state is approximately 233,000 individuals (with a range between 165,000 and 334,000). However, Grasshopper Sparrow populations are declining in Virginia. North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) data showed a significant decrease in its population of 1.83% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 8). Between Atlases, BBS data revealed that declines have intensified, with a significant decrease of 4.42% per year in Virginia from 1987–2018. These declines are mirrored across the species’ range, where loss and degradation of grassland habitat has become a major threat (see Conservation section).

Figure 7: Grasshopper Sparrow relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 8: Grasshopper Sparrow population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Like other grassland bird species, the Grasshopper Sparrow is experiencing a significant population decline in Virginia and throughout its range; thus, the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan lists this species as a Tier IV Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Moderate Conservation Need) (VDWR 2025).

In addition, a variety of efforts are being implemented in the state to protect this species. Declines have been attributed to habitat loss and degradation, changing agricultural practices, and pesticide use (Ruth 2015; Vickery 2020). Intensive haying practices such as earlier first harvest dates and more frequent harvests per year can destroy nests and kill fledglings. Nonetheless, working agricultural landscapes are a key source of Grasshopper Sparrow habitat, so it is critical to target conservation on these lands. Grasslands managed for cultural significance in partnership with farmers, such as in the national battlefield parks, can work in conjunction to these working lands to provide stable habitat protected in the long-term within a developing landscape (Massa et al. 2024).

A collection of conservation organizations in the state work to study and conserve grassland birds on working lands, including partners with the Virginia Grassland Bird Initiative such as Smithsonian’s Virginia Working Landscapes and the Piedmont Environmental Council, alongside the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources. These groups provide a variety of resources to address grassland species declines in the Piedmont, Blue Ridge Mountain, and Shenandoah Valley regions. Resources include information on safe dates for haying and grazing to prevent nest failure, financial incentive programs for farmers, and management guidelines for grasslands and other important habitats (Vuocolo et al. 2016).

Grasshopper Sparrows can also act as an umbrella species for conservation of others that share their habitat, including Vesper Sparrows (Pooecetes gramineus) and Eastern Meadowlarks (Sturnella magna) (Ruth 2015).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Massa, M., E. R. Matthews, W. G. Shriver, and E. B. Cohen (2024). Response of grassland birds to management in national battlefield parks. Journal of Wildlife Management 88 :e22519. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.22519.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Ruth, J. M. (2015). Status assessment and conservation plan for the Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum), version 1.0. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Lakewood, CO, USA.

Vickery, P. D. (2020). Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Vuocolo, C., C. Sedgwick, S. Harding, F. Wolter, S. Capel, D. Pashley, and S. Heath (2016). Managing land in the Piedmont of Virginia for the benefit of birds and other wildlife: third edition. Piedmont Environmental Council, Warrenton, VA, USA.