Introduction

Graceful and small with golden slippers, the Snowy Egret dances its way through the shallows of Virginia’s coastal estuaries. The delicate plumes that adorn this species in the breeding season made it among the most coveted and most heavily hunted species in the late 19th century as the feathers were used as hat ornaments. Shooting adults during the breeding season had a twofold cost, leading invariably to nest failure and colony collapse. By the early 20th century, the Snowy Egret teetered on the edge of extirpation in Virginia, leading Bailey (1913) to warn that, “unless very stringent laws, with wardens to enforce them, are passed, this species will soon pass from our list of breeding birds forever.”

Luckily, swift passage of such laws to end the millinery trade, including the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, effectively ended the trade in bird feathers, saving Snowy Egrets and their relatives. Snowy Egrets rebounded strongly from the 1940s through the 1970s and became a familiar sight again in coastal marshes. However, as with many of our coastal waterbirds, booming recovery has given way to declines again as they face new threats to their foraging and breeding habitats.

Breeding Distribution

The Snowy Egret was well-covered during the Second Atlas by the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey, a coastal census conducted by the Center for Conservation Biology in collaboration with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) and The Nature Conservancy. The survey identifies nesting locations of this and other species that breed in colonies. Because the Snowy Egret only breeds within the survey area, there was no need to model its distribution. For information on where the species occurs in Virginia’s Coastal Plain, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

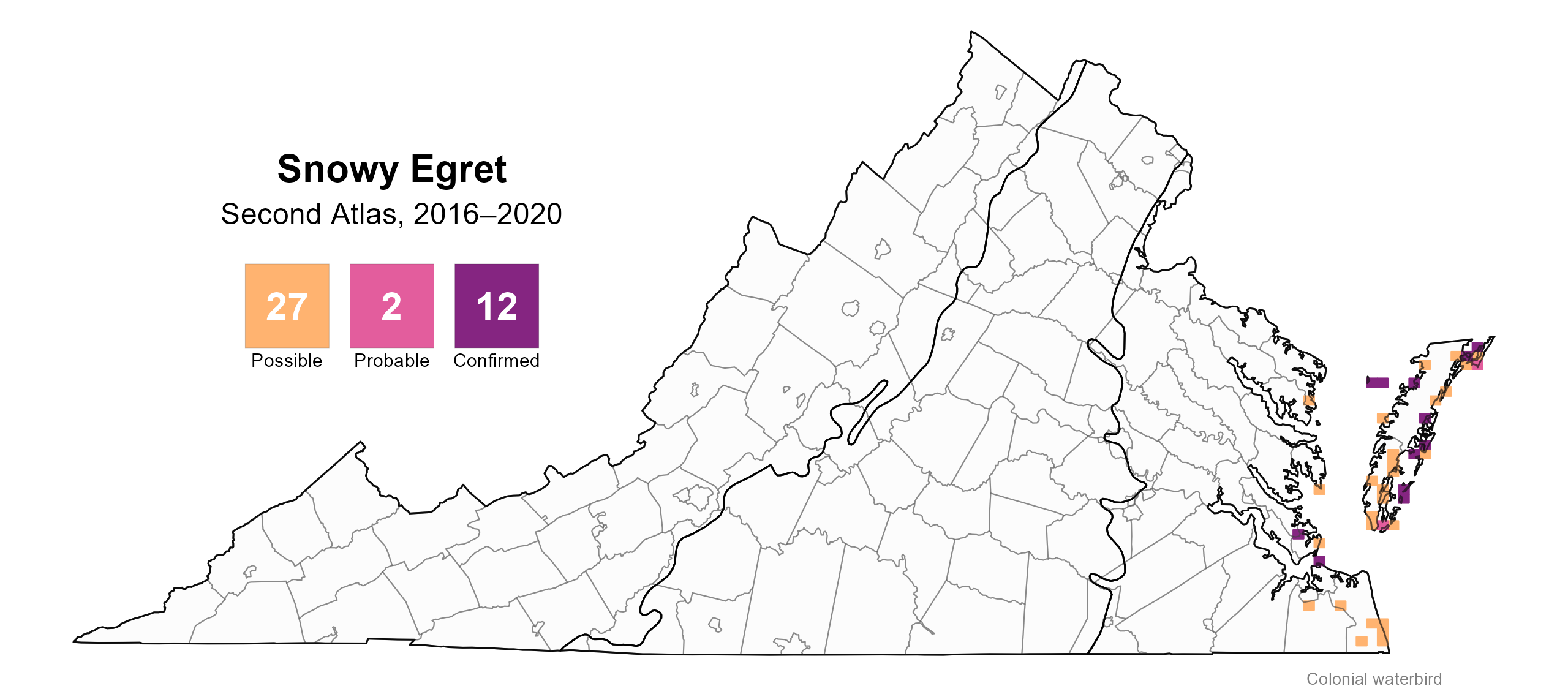

Snowy Egrets nest exclusively within the survey area covered by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey in 2018, and this survey documented the locations of breeding colonies of this species. Therefore, the species is unlikely to have nested in blocks without confirmed breeding evidence. Additional breeding confirmations were reported by Atlas volunteers in other years of the Second Atlas period.

Snowy Egrets were confirmed breeders in 12 blocks in three counties (Accomack, Northampton, and York) and the city of Hampton (Figure 1). On the Eastern Shore, colonies were documented both bayside and seaside. Bayside, Snowy Egrets nested in marshes bordering Pocomoke Sound and Tangier Island. Seaside, they occupied several barrier island heronries, including their largest known colony at Wires Narrow Marsh along the Chincoteague Causeway, which hosts more than 500 individuals (Watts et al. 2019).

Inland, Snowy Egrets nested on the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (HRBT) and in a small colony at Big Bethel Reservoir in Yorktown, marking their furthest inland breeding record during the Second Atlas. The locations of colonies change over time. For example, between 2013 and 2023, the colony on Mumford Island in the York River was lost to sea-level rise. During that same period, new mixed-species heronries were established on Little Cobb Island and Ship Shoal Island (Watts et al. 2024).

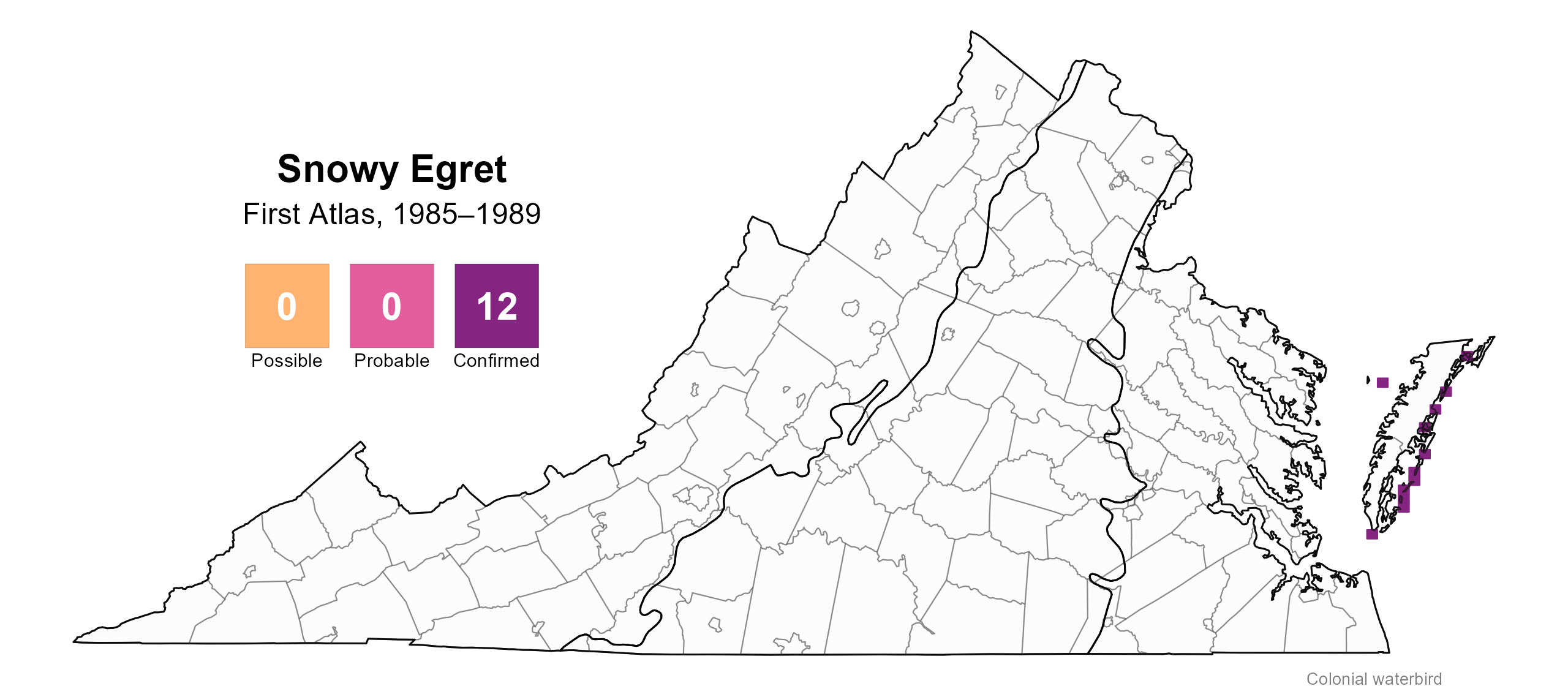

Previously, there were a few breeding records of Snowy Egrets away from the Chesapeake Bay. Previous records include a colony in Gloucester and, prior to the First Atlas, one record from 1978 of a nest on the James River near Hopewell (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). During the First Atlas, breeding was confirmed in 12 blocks, including at Fisherman’s Island National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) on the southern tip of Northampton County (Figure 2). That site was unoccupied by the time of the Second Atlas.

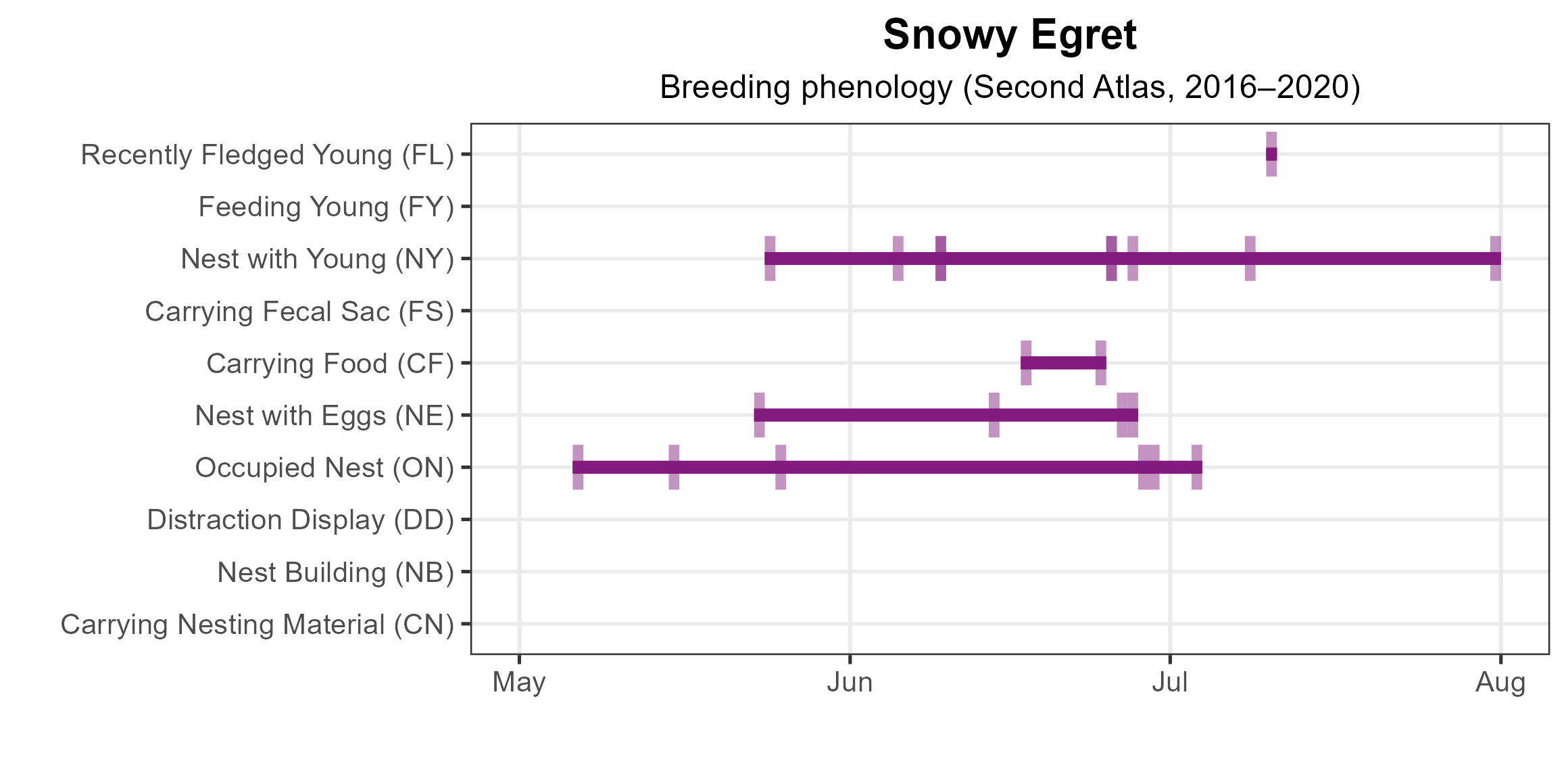

Snowy Egrets were observed on nests from May 6 to July 3. Eggs were observed in the nests from May 23 to June 27, and young from May 24 to July 31 (Figure 3). For more general information on the breeding habits of the Snowy Egret, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Snowy Egret breeding observations from the Second Atlas. The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category. Nesting is unlikely outside of confirmed blocks.

Figure 2: Snowy Egret breeding observations from the First Atlas. The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Snowy Egret phenology: confirmed breeding codes (Second Atlas). This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

The Snowy Egret had too few detections during the Atlas point count surveys to develop an abundance model. However, the distribution and size of Snowy Egret colonies derived from the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey are displayed on the CCB Mapping Portal.

Population trends are best tracked through targeted surveys of colonial nesting birds, and the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Surveys indicate a long-term decline in the population, particularly on barrier islands. Standardized surveys beginning in 1993 documented a sharp drop from 2,329 breeding pairs in that year to approximately 900 pairs in subsequent surveys, reaching a new low of just 751 pairs in 2023 (Watts et al. 2019, 2024; Figure 4).

Figure 4: Snowy Egret population trend for Virginia’s Coastal Plain. This chart illustrates the number of breeding pairs as estimated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey (Watts et al. 2024). A data point is not included for 1998, as the Survey covered a smaller geographic area in that year. The vertical light blue bars represent the periods corresponding to the First Atlas (1985–1989) and Second Atlas (2016–2020).

Conservation

The Snowy Egret is classified as a Tier II Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Very High Conservation Need) in the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan (VDWR 2025). The steep decline in Virginia’s breeding population since 1993 is a true cause for concern. It faces many of the same threats as other colonial waterbirds. These include loss and degradation of breeding habitat due to development, sea-level rise, erosion of nesting islands (Watts et al. 2019), and unknown factors related to prey abundance, availability, and quality.

To support long-term conservation, management can focus on protecting current colony sites and securing future inshore breeding habitat as the sea level rises and implementing predator control where necessary. The loss of the Mumford Island colony is a recent example of how sea-level rise is already affecting this species.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Bailey, H. H. (1913). The birds of Virginia. J.P. Bell Company, Incorporated, Lynchburg, VA, USA.

Parsons, K. C., and T. L. Master (2020). Snowy Egret (Egretta thula), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.snoegr.01.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. Boettcher, and A. L. Wilke (2019). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2018 breeding season. College of William & Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University CCBTR-19-06. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. Boettcher, and A. L. Wilke (2024). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2023 breeding season. College of William & Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University CCBTR-24-12. Williamsburg, VA, USA.