Introduction

The largest of North America’s rails, the King Rail breeds in both freshwater and brackish marshes of the Commonwealth (Wilson et al. 2007). There, it nests in shallow water amid dense vegetation, such as big cordgrass (Spartina cynosuroides) and arrow arum (Peltandra virginica) (Wilson and Watts 2012). It has a varied diet, feeding on crayfish, crabs, clams, and even a variety of vertebrates, such as snakes and frogs (Pickens and Meanley 2020).

King Rails are more often heard than seen, being extremely secretive and difficult to detect within dense marsh vegetation. Within brackish marshes, they can co-occur with the more abundant Clapper Rail (Rallus crepitans), with which it is known to hybridize. The two species have similar vocalizations, which can make it difficult to distinguish between them by voice alone. By sight, however, the difference between them is obvious; the King Rail sports an orange breast and belly and dark flanks with white bars, in obvious contrast to the drabber Clapper Rail.

Breeding Distribution

The King Rail breeds primarily in the Coastal Plain region, in marshes along the tidal tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay and of freshwater bodies such as Back Bay and the North Landing River. It can also be found outside this region, mostly occurring in wet meadows, drainage ditches, and impoundments (Wilson and Watts 2012). Due to limited data, distribution models could not be developed. Please see the Breeding Evidence section for more information on breeding distribution.

Breeding Evidence

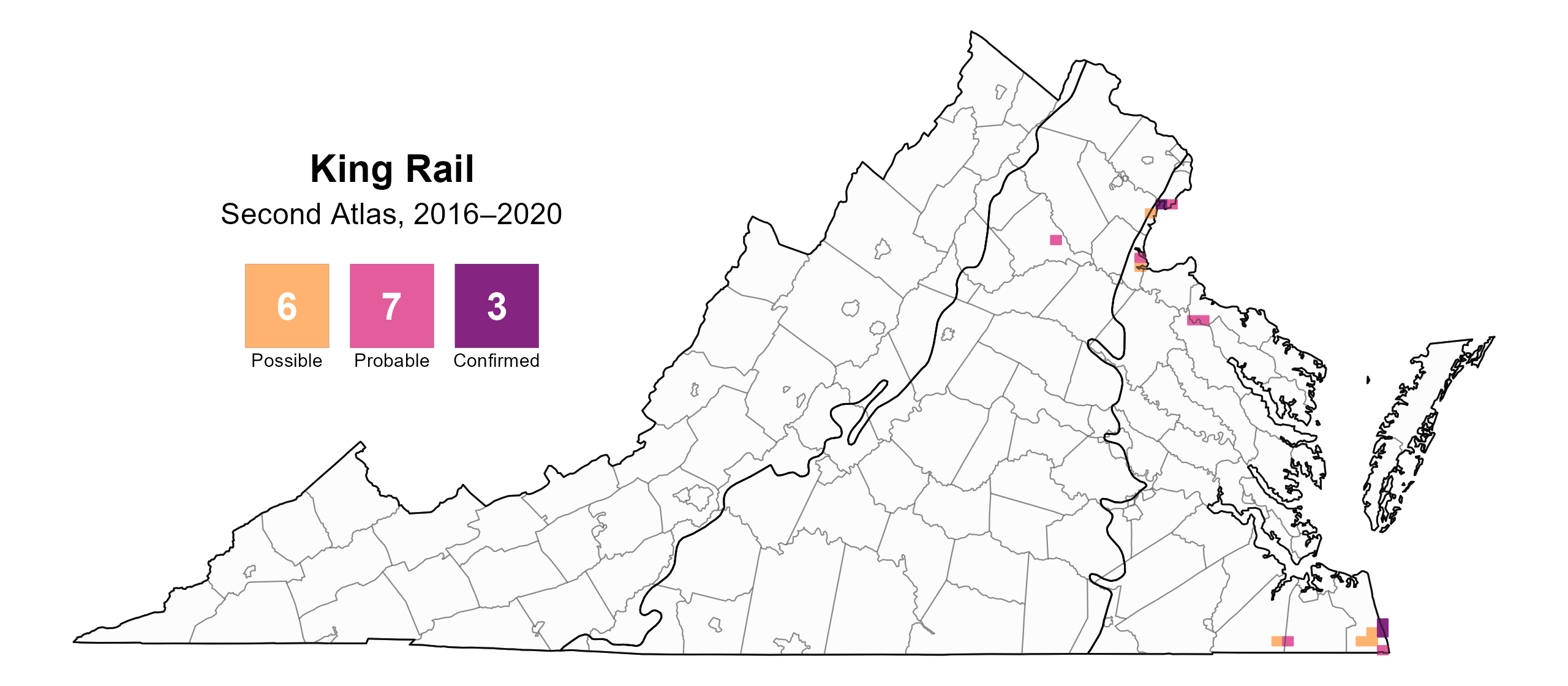

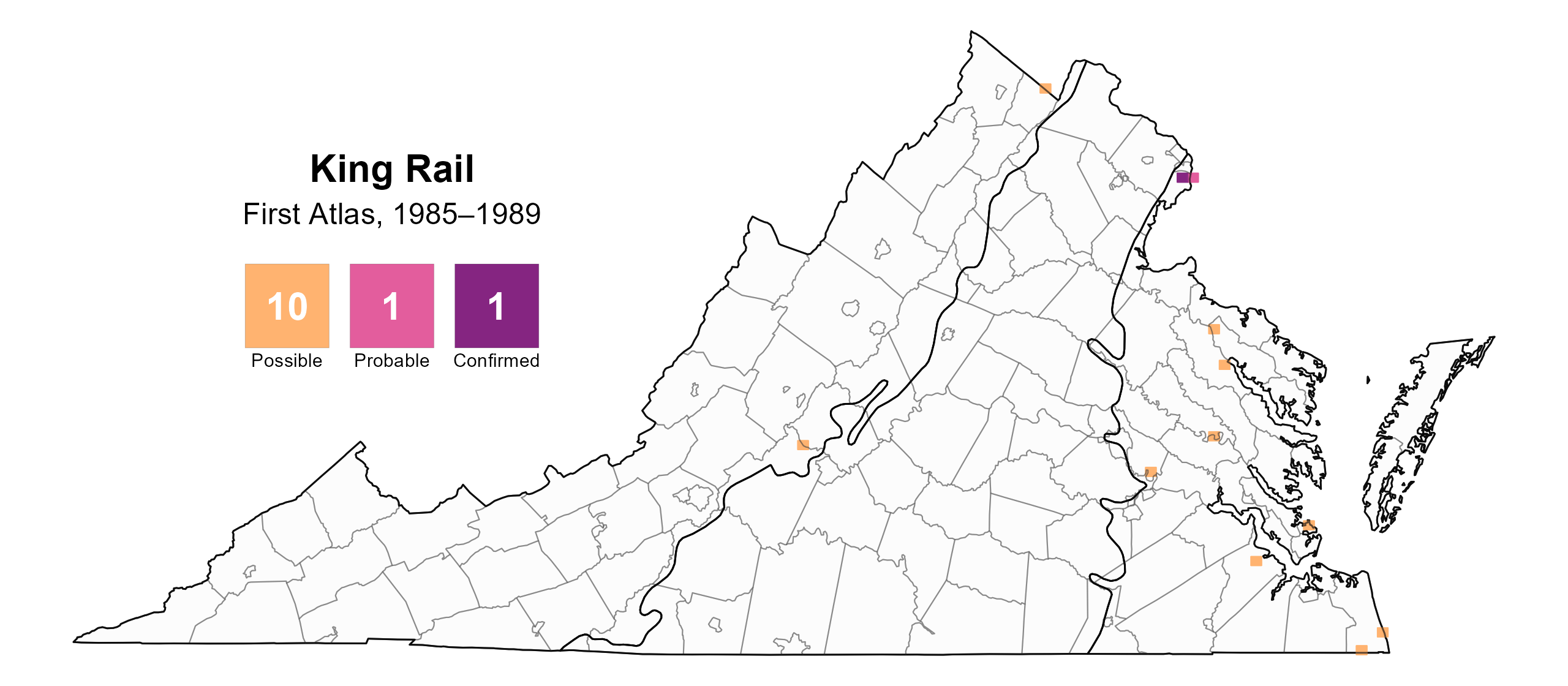

Except for one block in the Piedmont region, the King Rail was documented only in the Coastal Plain region (Figure 1). There, it was a confirmed breeder within one block at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) in Prince William County and in two blocks at Back Bay NWR in Virginia Beach. It was found to be a probable breeder at additional Coastal Plain sites on the Potomac River (Mason Neck NWR in Fairfax County and Aquia Landing Park in Stafford County), on the Rappahannock River (Otterburn Marsh in Essex County and Drake Marsh in Westmoreland County), in Great Dismal Swamp NWR in the city of Suffolk, and at False Cape State Park in Virginia Beach (Figure 1). In the Piedmont, it was documented as a probable breeder at the Thoms Road wetland area in Culpeper County. During the First Atlas, only one confirmed breeder was recorded, and it was in Fairfax County (Figure 2). The number of blocks where King Rails were documented was similar between Atlases, with 12 blocks during the First Atlas and 16 blocks during the Second Atlas.

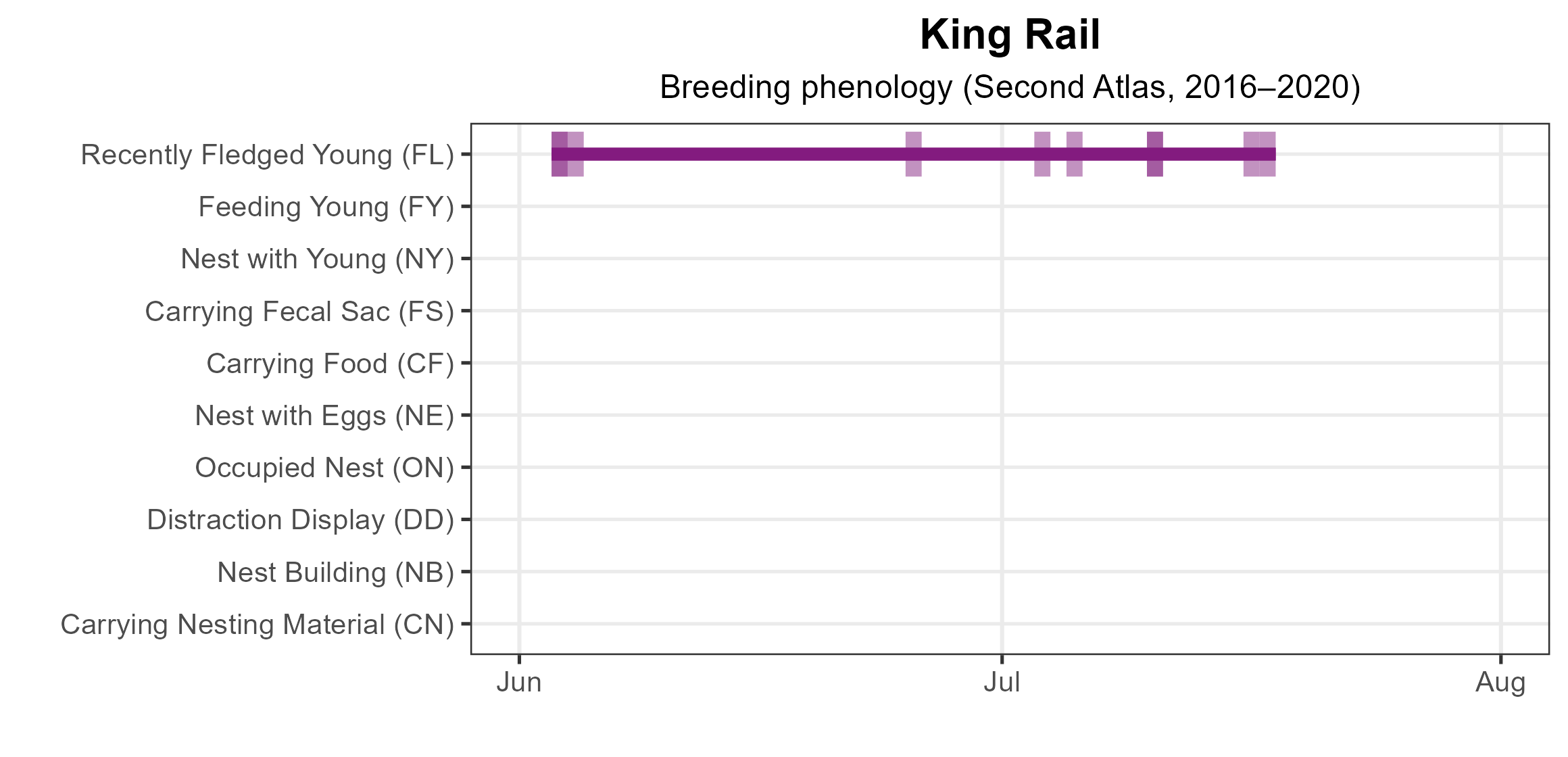

Breeding was confirmed only by observations of recently fledged young (June 3 to July 17). For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: King Rail breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: King Rail breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: King Rail phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

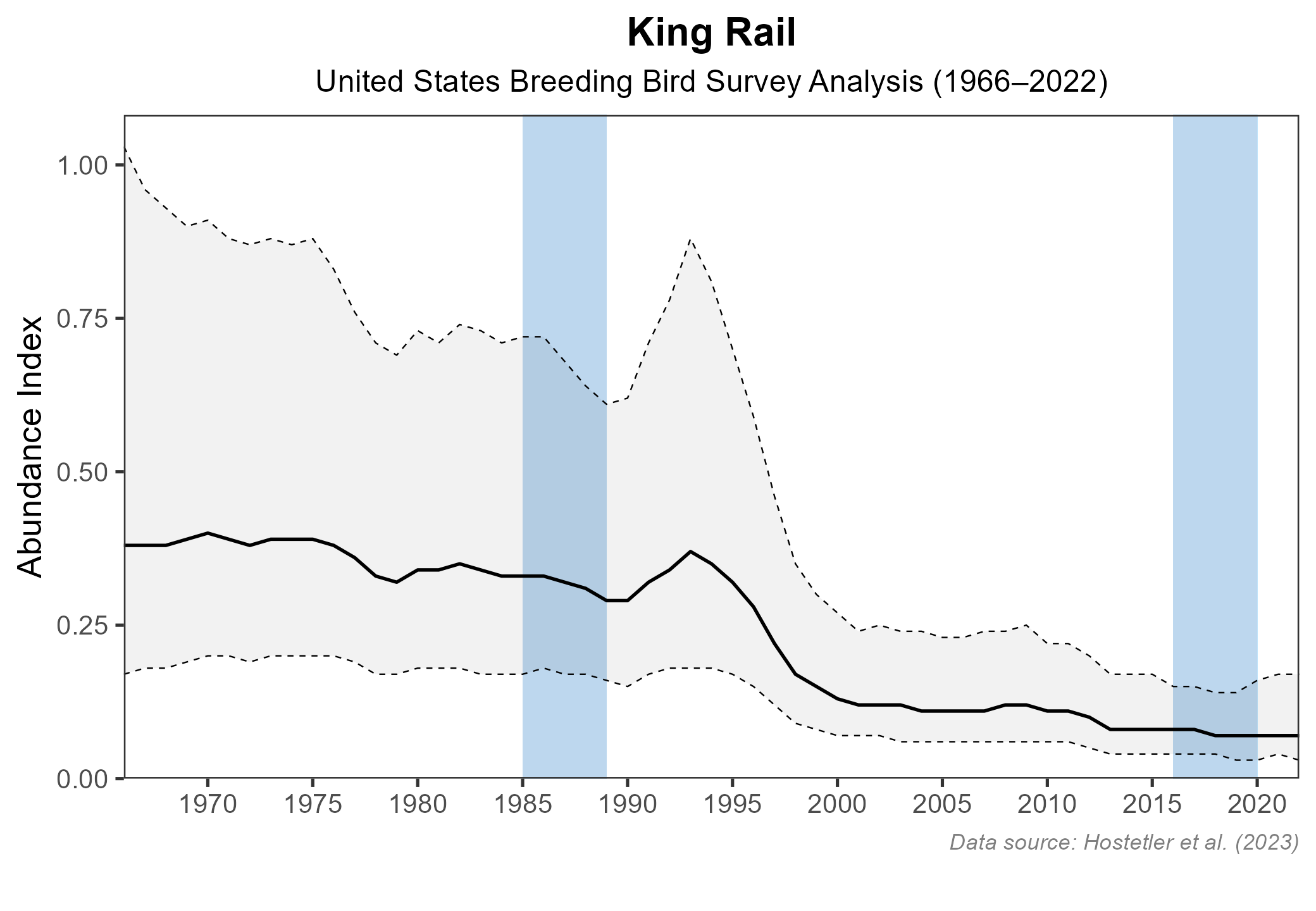

The Atlas point count effort did not adequately survey King Rail habitat, and the species was not detected; thus, no abundance model could be developed. However, the species is known from relatively few sites in the Coastal Plain, where it is considered uncommon to locally common (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). Therefore, it is not believed to have a large population. Additionally, the King Rail is not detected by the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) in Virginia. Although credible regional population trends for the species could not be generated from BBS data, the U.S. BBS trend shows a significant 2.95% annual decline from 1966–2022 and an even larger significant annual decline of 4.81% between Atlases (1987–2018) (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 4)

Figure 4: King Rail population trend for the United States as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

The King Rail is a declining marsh bird with a poorly documented breeding distribution within Virginia. Given its ongoing decline and what is believed to be a small population, Virginia’s 2025 Wildlife Action Plan includes the King Rail as a Tier I Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Critical Conservation Need), indicating it is at high risk of extirpation (VDWR 2025).

Certain areas where King Rails occur are well-documented. However, more work is needed to properly understand its broader distribution within the Coastal Plain. This can be challenging in areas where its distribution overlaps with that of the Clapper Rail. Because of the similarity in their vocalizations, identification based on calls alone can be inconclusive. One strategy would be to focus surveys on freshwater marshes, where Clapper Rails are known not to occur. Over the years, the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) has conducted marsh bird surveys by boat in some of these areas, but on a limited basis. These should be expanded and coordinated with similar surveys by other entities.

Like other marsh birds, King Rails in Virginia are vulnerable to loss of their marsh habitat from coastal development and climate-driven sea-level rise. The latter can also lead to saltwater migration further upstream (Rice et al. 2011). These higher salinities can cause expansion of brackish marshes into formerly freshwater areas, which could lead to increased competition and hybridization between King and Clapper Rail. In fact, genetic analyses of birds sampled in Virginia and in other mid- and southern Atlantic states suggest that Clapper Rails may be displacing King Rails in brackish marshes of the Commonwealth (Coster et al. 2018). Conversion of cordgrass stands preferred by King Rail to thick stands of the non-native common reed (Phragmites australis) is also of concern (Wilson et al. 2007). Ultimately, the identification, protection, and management (e.g., Phragmites control) of suitable marshes will be necessary to ensure continued availability of habitat for this species in the face of constantly changing conditions (VDWR 2025).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Coster, S. S., Welsh, A. B., Costanzo, G., Harding, S. R., Anderson, J. T., McRae, S. B. and Katzner, T. E. (2018). Genetic analyses reveal cryptic introgression in secretive marsh bird populations. Ecology and Evolution 8:9870–9879. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.4472.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Pickens, B. A. and B. Meanley (2020). King Rail (Rallus elegans), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.kinrai4.01.

Rice, K.C., M. R. Bennett, and S. Jian (2011). Simulated changes in salinity in the York and Chickahominy Rivers from projected sea-level rise in Chesapeake Bay: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2011–1191, 31 p.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Wilson, M. D., B. D. Watts and D. F. Brinker (2007). Status review of Chesapeake Bay marsh lands and breeding marsh birds. Waterbirds 30:122–137, 116.

Wilson, M. and B. Watts (2012). The Virginia avian heritage project: A report to summarize the Virginia avian heritage database. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA, USA.