Introduction

The Yellow-breasted Chat is a distinctive bird that has intrigued ornithologists due to its uncertain taxonomic placement. Once classified with warblers, in 2017, it was recognized as belonging to its own unique family (Chesser et al. 2017). It is a common transient migrant and summer resident throughout the state (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). Despite its wide distribution in Virginia, the Yellow-breasted Chat is always a surprising and memorable sight for birdwatchers. This bird is more often heard than seen, as it whistles, rattles, and barks from within dense, shrubby vegetation, rarely emerging except for display flights (Thompson and Eckerle 2022).

Breeding Distribution

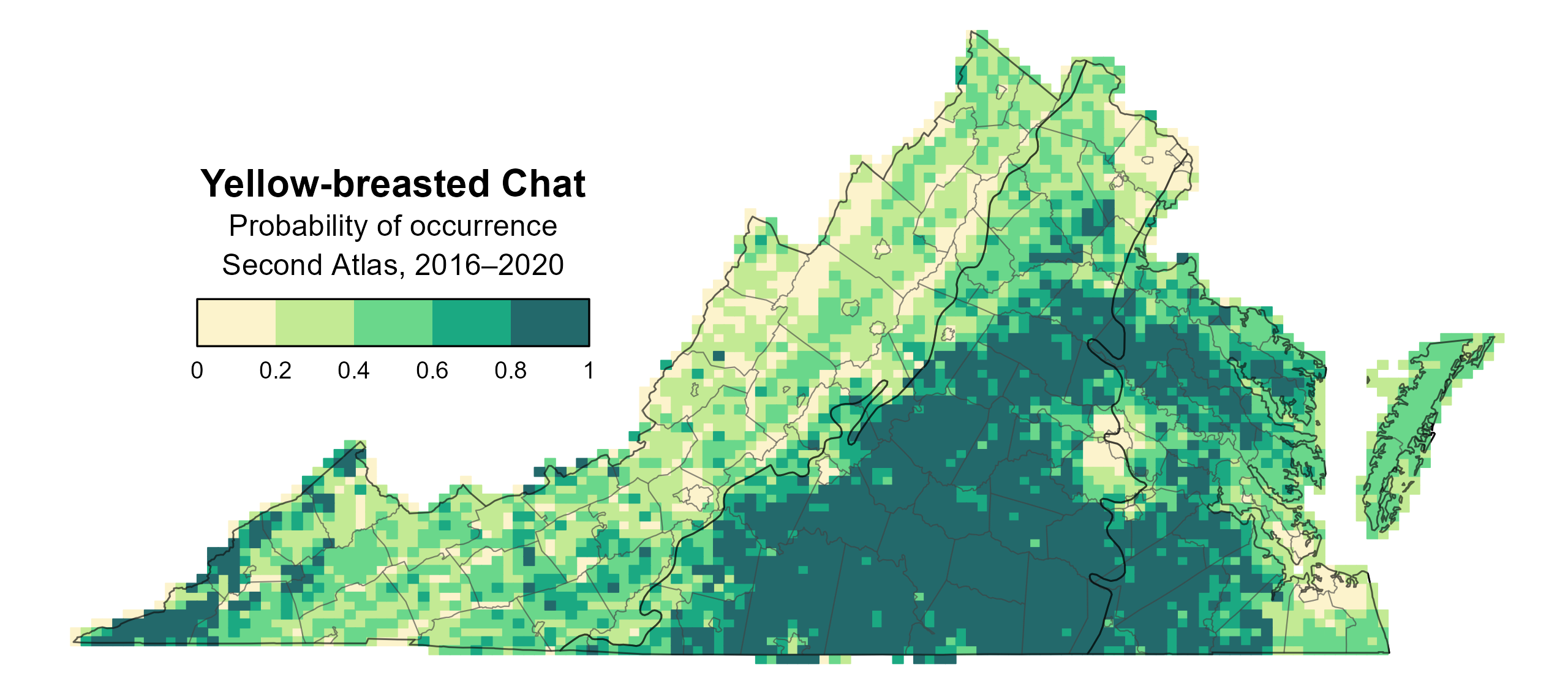

Yellow-breasted Chats are found in all regions of the state, but they are most likely to occur in the southern Piedmont and inner Coastal Plain regions, as well as the southwestern corner of the state in the Cumberland Mountains (Figure 1). Chats are also likely to occur patchily in suitable shrubland habitats across the Mountains and Valleys region. They are least likely to be found in urban areas, such as Richmond and Northern Virginia, or at high elevations along the forested Blue Ridge Mountains (Figure 1).

The likelihood of Yellow-breasted Chat occurrence increases with the proportion of shrubland and grassland habitats within a block. They are also more likely to occur in areas with a greater number of habitat types, indicating that early successional habitats with high amounts of structural diversity, including open areas, are where chats thrive. Conversely, forests are a negative predictor of their occurrence. Yellow-breasted Chats are less likely to be found in blocks with extensive forest cover and larger forest patches, as the species does not typically inhabit closed-canopy forests.

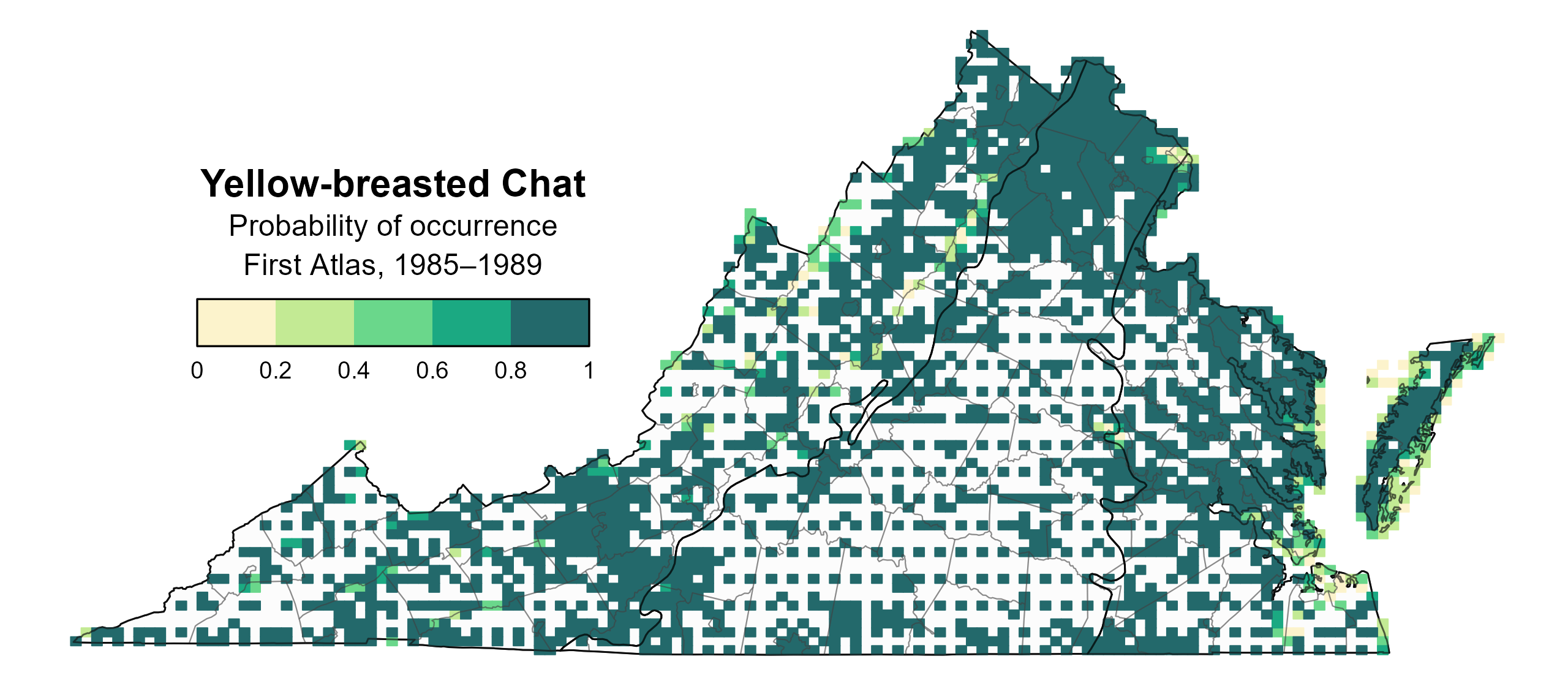

From the First Atlas to the Second Atlas (Figures 1 and 2), the Yellow-breasted Chat’s likely occurrence decreased substantially throughout the entire Mountains and Valleys region and in urban areas across the state (Figure 3). This change indicates a drastic decline in their occurrence, remaining stable only in the central and southern Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Yellow-breasted Chat breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Yellow-breasted Chat breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Yellow-breasted Chat change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

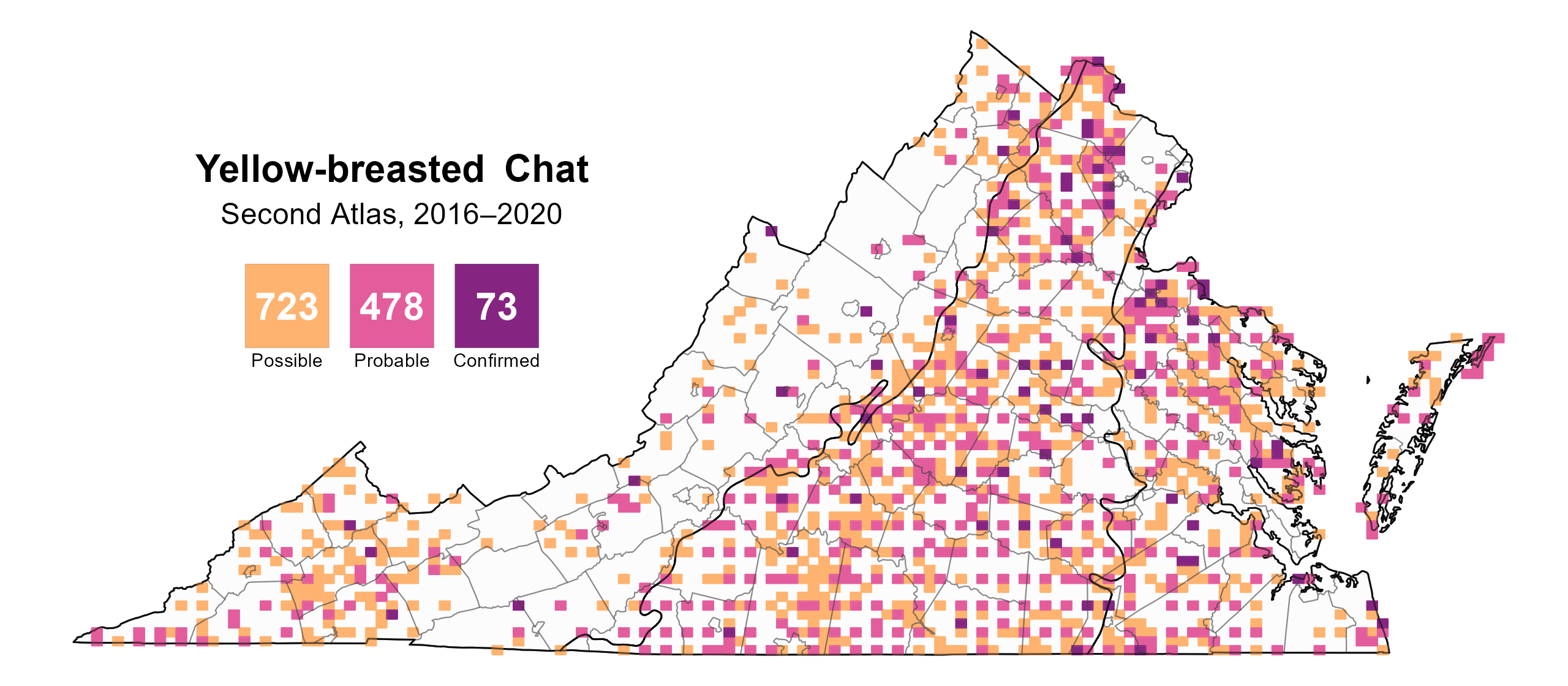

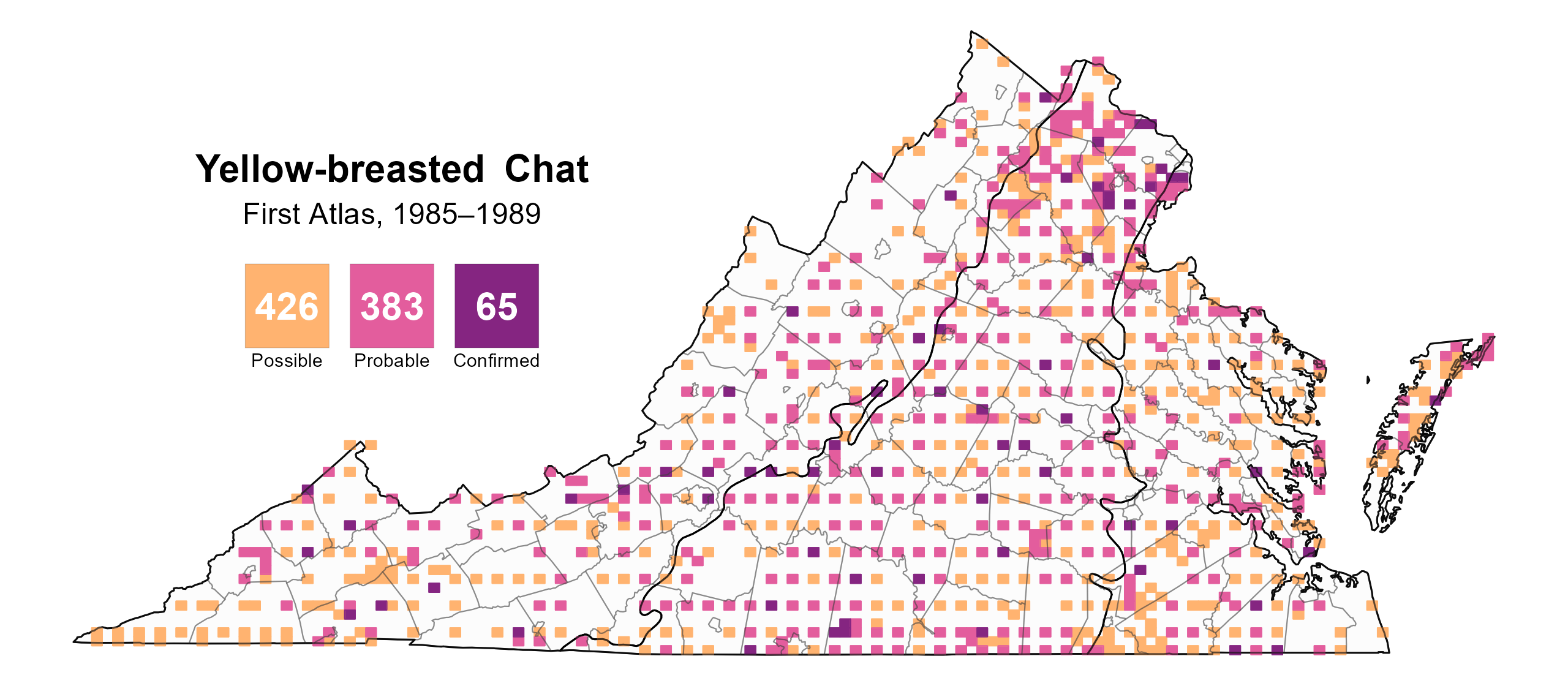

Yellow-breasted Chats were confirmed breeders in 73 blocks and 44 counties and probable breeders in an additional 52 counties (Figure 4). Chats were unique in that they were often observed but seldomly confirmed due to their skulking habits. The pattern of breeding observations in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions were similar between Atlases, but there were fewer observations recorded in the Mountains and Valleys region during the Second Atlas, which is consistent with its population decrease in the state (see Population Status) (Figure 5).

Yellow-breast Chat’s skulking behavior is also reflected in the behaviors used to confirm breeding. Most observations were of adults carrying food, and nests were rarely found (Figure 6). Breeding was first documented on May 7, when birds were seen carrying nesting material, and fledglings were seen as late as August 1. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Yellow-breasted Chat, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Yellow-breasted Chat breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Yellow-breasted Chat breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Yellow-breasted Chat phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

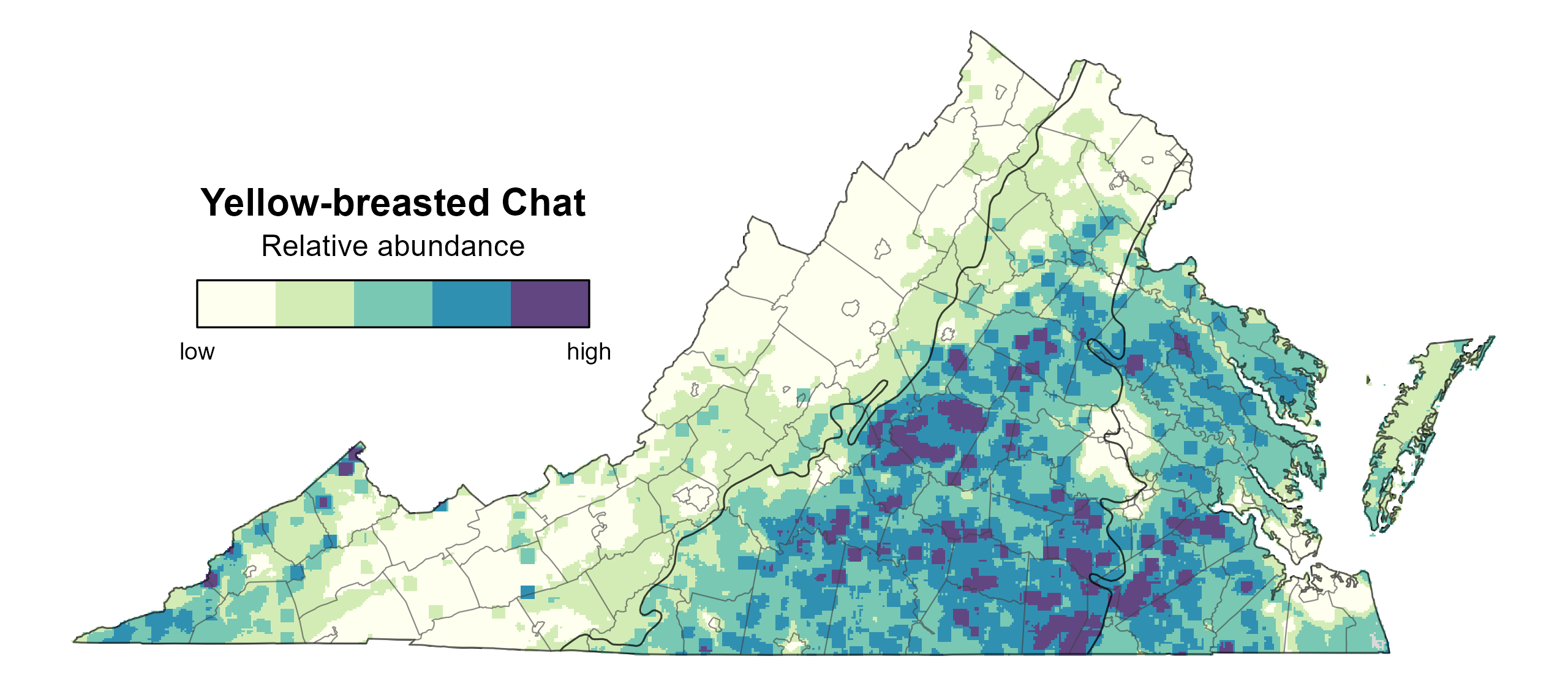

Yellow-breasted Chat relative abundance was estimated to be highest in the central and southern Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions and low to moderate wherever suitable shrubland habitat was available (Figure 7).

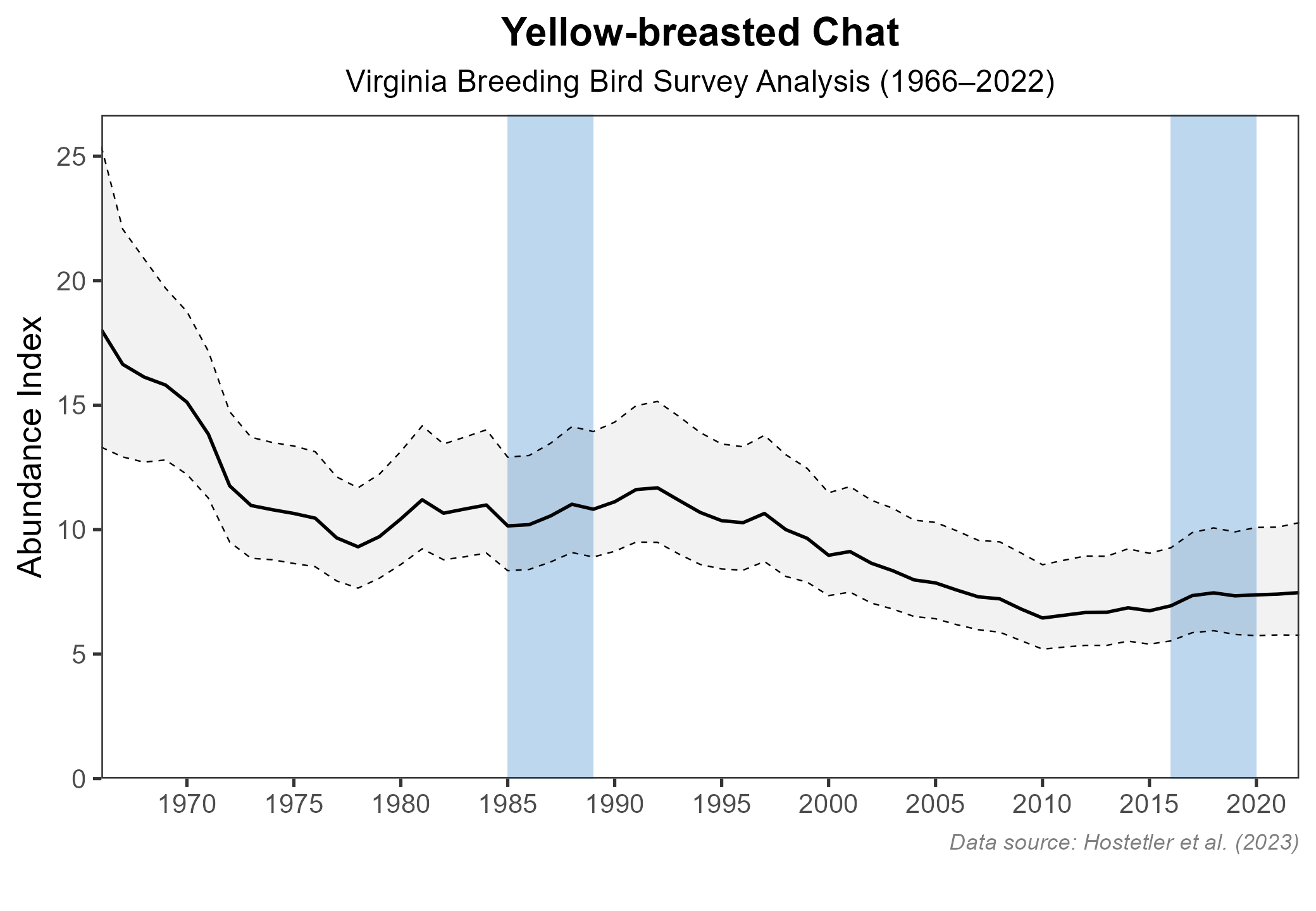

The total estimated Yellow-breasted Chat population in Virginia is approximately 336,000 individuals (with a range between 246,000 and 469,000). However, Yellow-breasted Chat populations are declining in the state. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) trend for Virginia showed a significant decrease of 1.55% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 8). Between the First and Second Atlases, BBS data showed a similar significant decline of 1.11% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 7: Yellow-breasted Chat relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 8: Yellow-breasted Chat population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Population declines are primarily due to habitat loss and degradation caused by deforestation, urban development, and invasive species such as kudzu (Pueraria montana) (Thompson and Eckerle 2022). Given its declining numbers, the Yellow-breasted Chat is classified as a Tier IV Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Moderate Conservation Need) in Virginia’s 2025 Wildlife Action Plan, indicating that its population is likely declining and long-term planning is needed (VDWR 2025).

As a species that relies on shrubland and grassland habitats, the preservation and management of shrubby, open areas are crucial for its survival. Promoting land management practices that maintain or create these habitats, such as controlled burns, selective bush hogging, and the preservation of natural forest edges, could help mitigate the negative impacts on Yellow-breasted Chat populations and support their recovery in Virginia. Areas that are permanently subject to management, such as powerline cuts, can be beneficial to their populations.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Chesser, R. T., K. J. Burns, C. Cicero, J. L. Dunn, A. W. Kratter, I. J. Lovette, P. C. Rasmussen, J. V. Remsen, J. D. Rising, D. F. Stotz, and K. Winker (2017). Fifty-eighth supplement to the American Ornithological Society’s check-list of North American birds. The Auk 134:751–773.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Thompson, C. F. and K. P. Eckerle (2022). Yellow-breasted Chat (Icteria virens), version 2.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald and B. K. Keeney, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.yebcha.02.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.