Introduction

Perhaps our most familiar waterbird, the Great Blue Heron’s graceful posture and distinct blue-gray plumage make it easily identifiable by birders of all skill levels. This species is highly adaptable, equally at home in coastal marshes or in retention ponds as long as there is sufficient prey. Their breeding locations, called rookeries, heronries, or just colonies, are usually located along shorelines and in swamp habitat away from human disturbance (Clements 1995). In Virginia, most nest in bottomland hardwood forest, often in large trees such as American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) (Byrd and Beck 1985), or in human structures to hold their large nests that are constructed with sticks. Colonies return to the same areas year after year.

Breeding Distribution

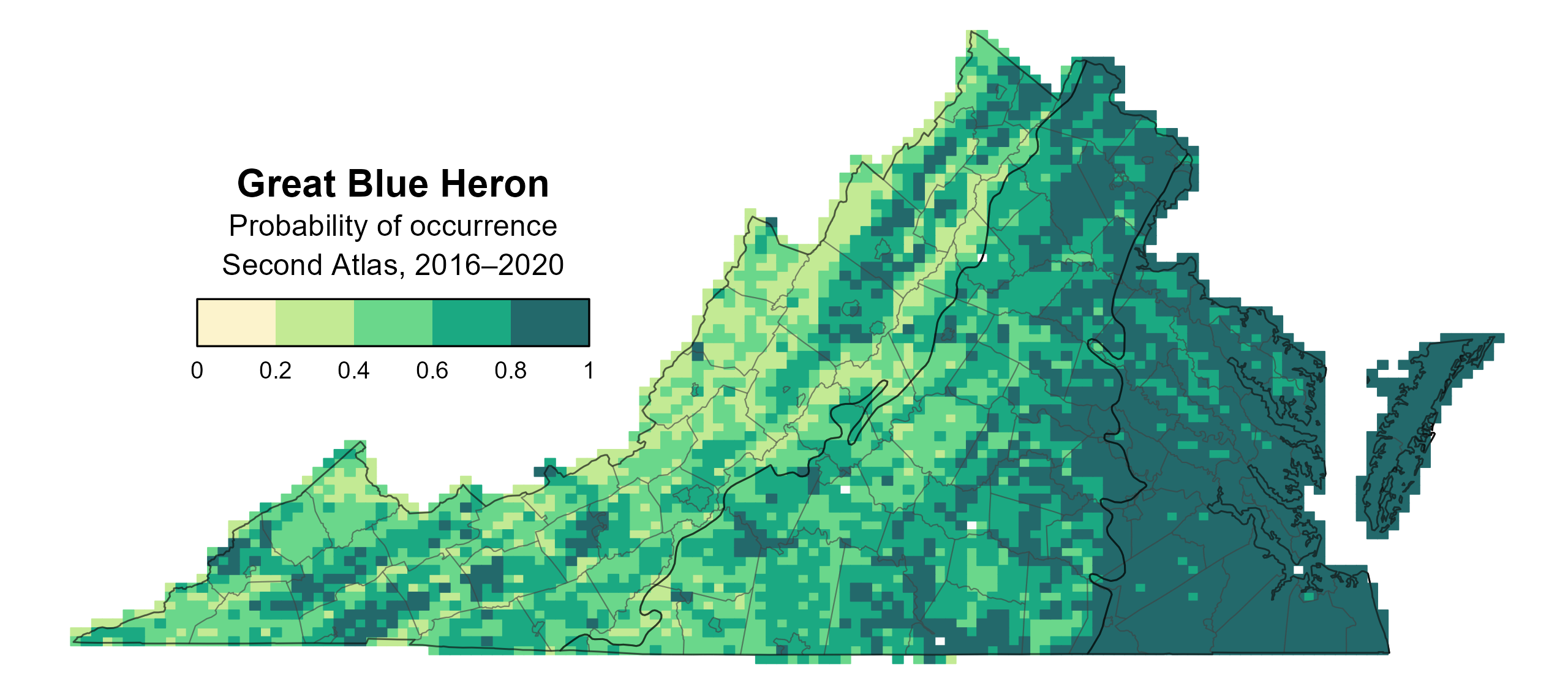

Great Blue Herons are found in all regions of the state but are most likely to occur in the Coastal Plain region and along major waterways into the Piedmont region. They are less likely to occur along waterways in the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains (Figure 1). The likelihood of a Great Blue Heron occurring in a block increases with the amount of forest edge but decreases with the amount of forest cover. Great Blue Herons are also less likely in blocks that have a high proportion of agricultural lands, developed areas, or grassland and shrubland habitat.

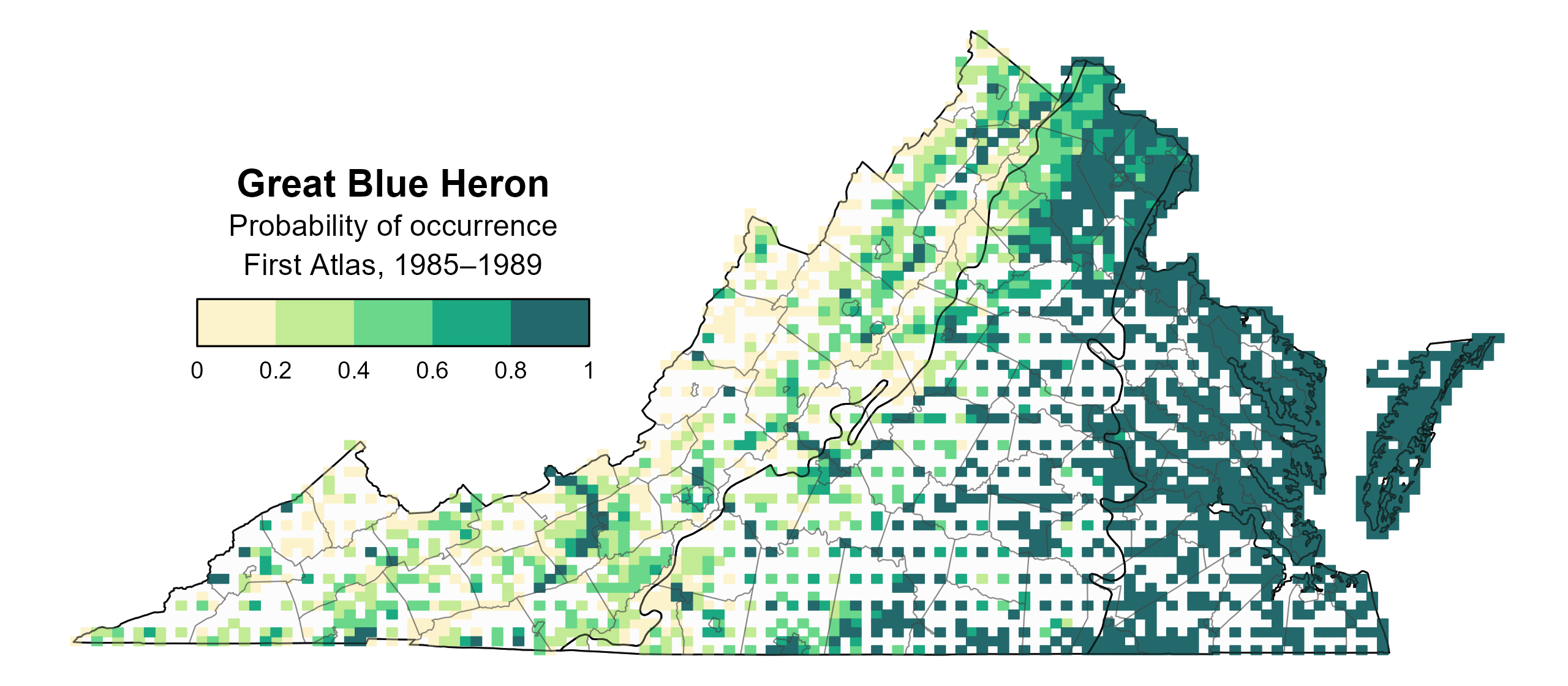

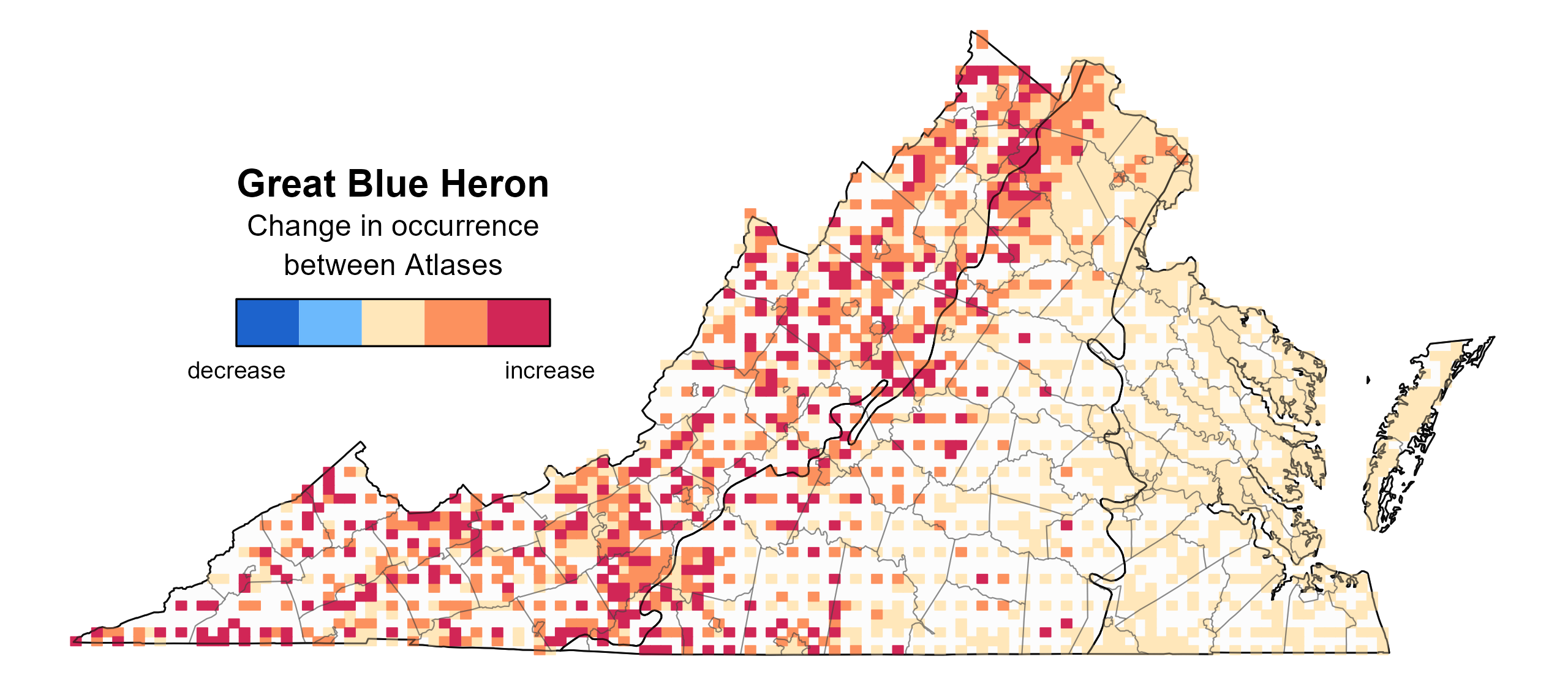

The likely occurrence of Great Blue Herons increased from the First Atlas to the Second Atlas throughout the western Piedmont region and all the Mountains and Valleys region (Figures 1 to 3). In accordance with their expanding population (see Population Status section), they have become a much more common sight, even in the mountains.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Great Blue Heron breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Great Blue Heron breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Great Blue Heron change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

Volunteers observed Great Blue Herons breeding in all regions of the state. They were confirmed breeders in 172 blocks and 68 counties and probable breeders in an additional four counties (Figure 4). Confirmations were concentrated in the Coastal Plain region, but numerous confirmations and sightings inland attest to the species’ adaptability and expanding distribution. This wide distribution of breeding observations is in stark contrast to the First Atlas, where the only confirmations outside of the Coastal Plain and eastern Piedmont were in Highland and Roanoke Counties (Figure 5). Rookeries are often located in remote, difficult-to-access areas; thus, many more blocks were merely possible. Furthermore, because birds can travel long distances between foraging sites and rookeries, many of these possible sightings may not indicate a rookery location.

Nesting began early, with adults observed occupying nests at rookeries as early as February 10 (Figure 6). Active construction began shortly thereafter, with active nest work from February 16 through May 19. The bird in Virginia Beach was carrying nesting material on March 1, and the a in Highland was carrying food on May 18. Rookeries should not be closely approached for risk of disturbance; thus, only three observations were made of eggs in the nest. Breeding continued to be documented through August 17 with the last observations of recent fledglings. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Great Blue Heron, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Great Blue Heron breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Great Blue Heron breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Great Blue Heron phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

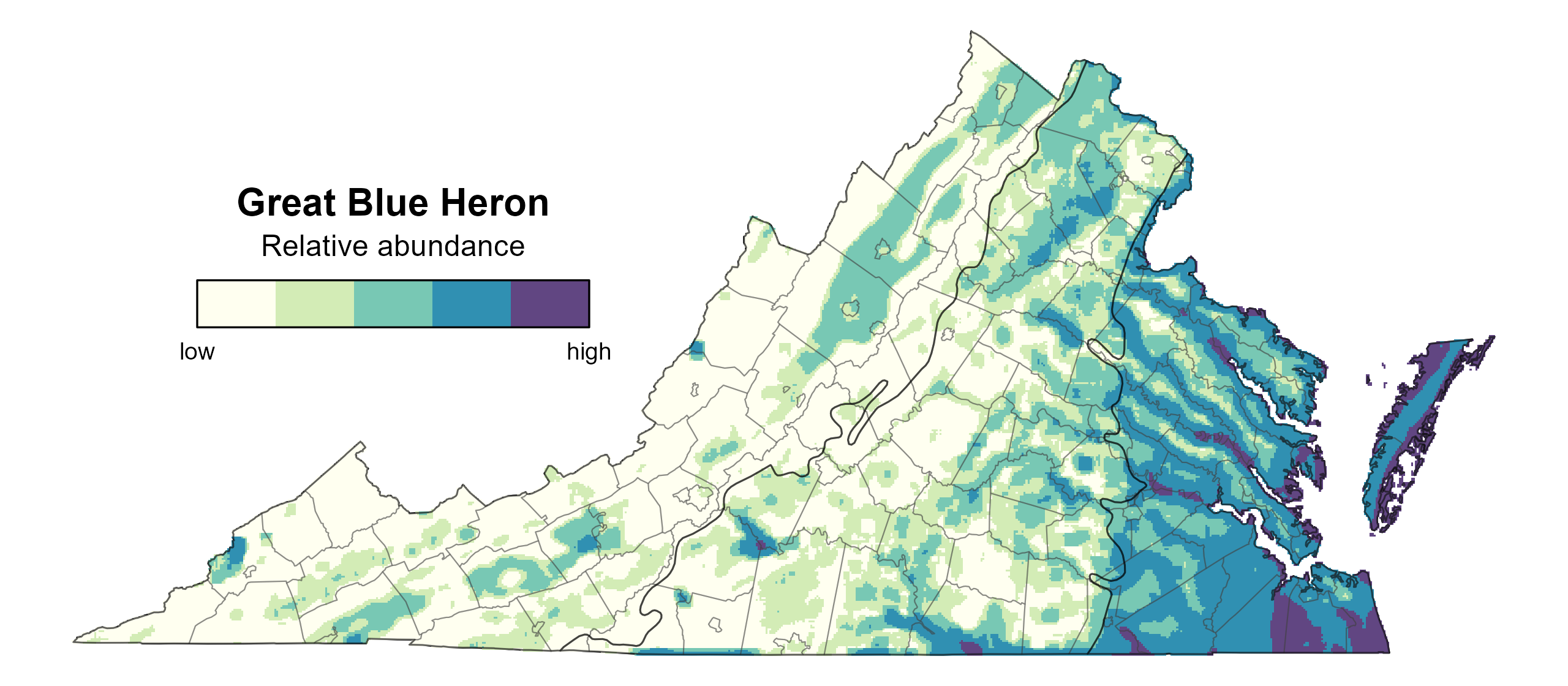

Great Blue Heron relative abundance was estimated to be highest in the marshes of the Coastal Plain, particularly on the Eastern Shore, in Virginia Beach, and in the Great Dismal Swamp (Figure 7). They were also predicted to have high abundance levels along all major rivers and on inland lakes, including Kerr Reservoir (Mecklenburg County) and Smith Mountain Lake (Bedford, Franklin, and Pittsylvania Counties).

The total estimated Great Blue Heron population in the state is approximately 73,000 individuals (with a range between 23,000 and 232,000). Great Blue Heron populations have dramatically increased in Virginia. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) showed that its population experienced a significant increase of 1.84% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 8). Between the First and Second Atlas, BBS data showed a similar trend, with a significant increase of 1.67% per year in Virginia from 1987–2018.

Additionally, the increase in Great Blue Herons has been closely monitored in the Coastal Plain region. By the time of the First Atlas, surveys by the Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) found 31 colonies with approximately 3,600 breeding pairs (Wilson and Watts 2012), which by 2013 had ballooned to 258 colonies and approximately 7,800 breeding pairs (Watts and Paxton 2014). They have not been surveyed since 2013 because of the high cost associated with aerial surveys for a species that is as widely distributed across the Coastal Plain as Great Blue Herons. Notably, a 15% decrease in the breeding population was detected between 2003 and 2013 perhaps due to the fragmentation of larger colonies, which reduced the average colony size. In addition to fragmentation, there has been a loss of historic colonies. Many major colonies from the 1970s and 1980s are no longer present (Watts and Paxton 2014).

Figure 7: Great Blue Heron relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 8: Great Blue Heron population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

The CCB monitors Great Blue Herons and other colonial waterbirds in the Coastal Plain with assistance from the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources and The Nature Conservancy. Because of their widespread distribution and seemingly stable abundance in the state, they are not a species of concern in Virginia. However, breeding birds are very vulnerable to predation and disturbance; thus, land managers should establish buffer zones around colonies and avoid any disturbance from February through July (Byrd and Beck 1985).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Byrd, M. A., and R. A. Beck (1985). Great Blue Heron management recommendations. CCBTR-85-04. Department of Biology, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Clements, K. H. (1995). Determinants of Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) colony size and location along the James and Chickahominy Rivers in Virginia. Master’s Thesis. College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. doi:10.21220/s2-v0mn-yf57.

Vennesland, R. G. and R. W. Butler (2020). Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.grbher3.01.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Watts, B. D, and B. J. Paxton (2014). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2013 breeding season. CCBTR-14-03. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. Boettcher, and A. L. Wilke (2019). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2018 breeding season. CCBTR-19-06. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Wilson, M. D., and B. D. Watts (2012). The Virginia avian heritage project: a report to summarize the Virginia avian heritage database. CBTR 12-04. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA, USA.