Written By: Sergio Harding

Breeding Bird Atlases (Atlases) have a long and distinguished history in Europe and North America, providing a catalogue of breeding birds within a defined geographic area and capturing a snapshot of the spatial distribution of those species in time. Within the U.S., such Atlases have taken place primarily at the state level, although county-level Atlases have also been implemented, including the Loudoun County Bird Atlas in Virginia (Ligi 2019). Virginia conducted its First Atlas between 1985 and 1989 (Trollinger and Reay 2001) through a partnership between the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (now Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources [VDWR]) and the Virginia Society of Ornithology (VSO). The Second Atlas was also carried out through a partnership between VDWR and VSO, with the addition of the Conservation Management Institute (CMI) at Virginia Tech.

The impetus behind repeating the Atlas, as many other states have done, was the recognition that bird populations are not static in time. Therefore, there is much conservation value to be gleaned from updating our understanding of changes in these populations. Data for the Second Atlas were collected between 2016 and 2020, roughly 30 years after the First Atlas. However, the foundation for the project was laid in 2013. At that time, a Planning Committee with representatives from the three partner organizations created a framework for the Atlas and developed a proposal for funding the work. Funding was ultimately provided by VDWR and VSO. An Atlas Steering Committee, also made up of representatives from the three partner organizations, oversaw the planning and implementation of the project during the data collection period through the Atlas Coordinator (see below). An overview of the data collection process during the Second Atlas is described in the following sections.

Volunteer-collected Atlas Data

Over 1,450 volunteer observers (hereafter volunteers) contributed data to the Second Atlas (see Acknowledgments). They included birders, ornithologists, academics, and natural resource professionals from government agencies and non-governmental organizations. Volunteers used a standardized Atlas methodology similar to that used in the First Atlas and by other state Atlases, with updates to reflect advancements in data collection tools and technologies.

Atlas Blocks

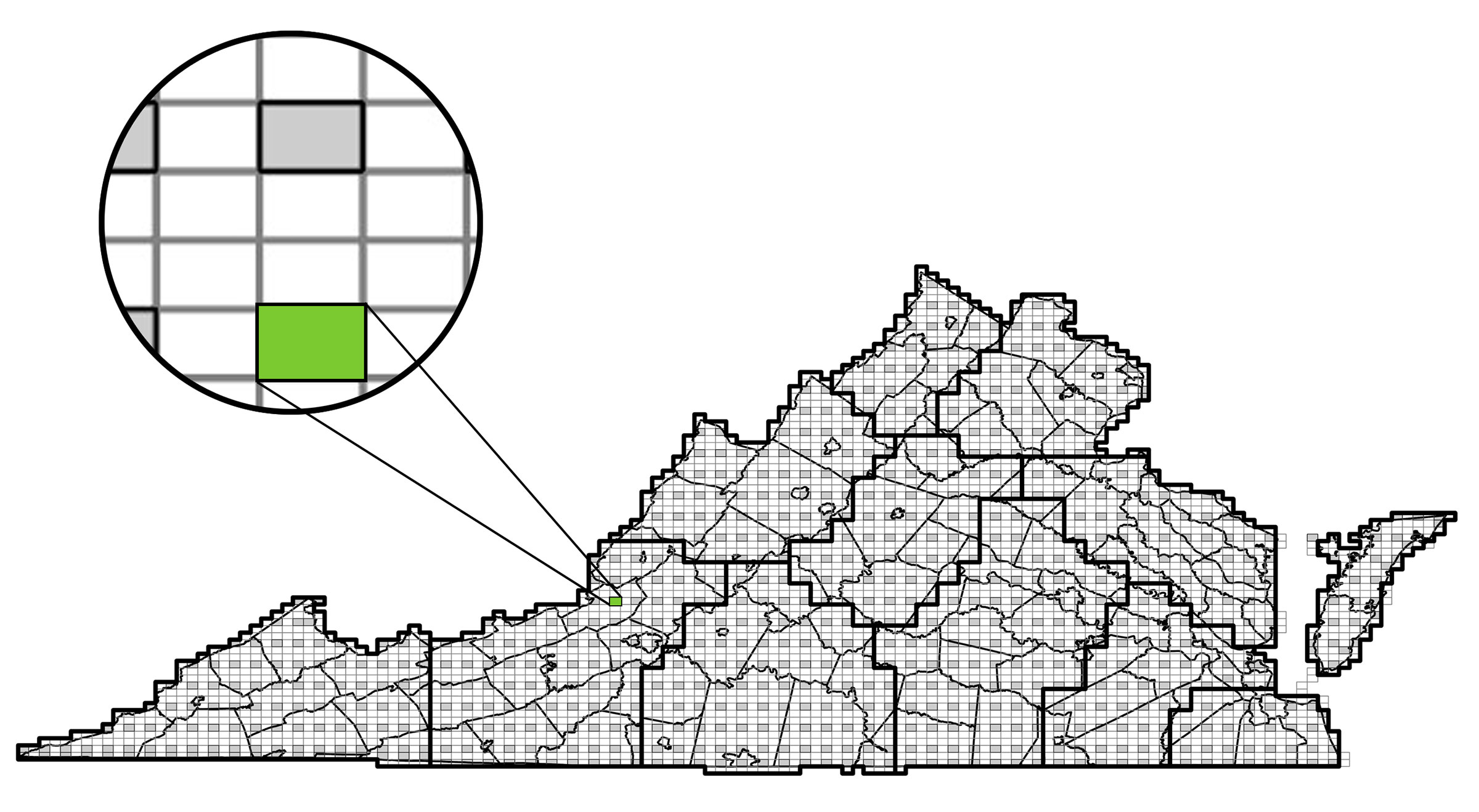

Data collection took place within individual survey units known as Atlas blocks. A block represents 1/6th of a 7.5 minute U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) topographic quadrangle map. Blocks ranged in area from 9.6 to 10.0 mi2 (24.8 to 25.9 km2). The block grid overlaying the state of Virginia consists of 4,421 blocks (Figure 1). This grid includes blocks that are not wholly contained within Virginia and instead cross state lines with neighboring West Virginia to the west, North Carolina to the south, and Maryland and the District of Colombia to the north. Additional blocks along the coastline and the Eastern Shore fall partially within the waters of the Chesapeake Bay and its major tributaries, as well as the Atlantic Ocean.

Figure 1. Map of Second Atlas regions (thick black lines), Atlas blocks and Atlas priority blocks (gray). Virginia county boundaries are represented by thinner black lines.

Given the sheer number of blocks covering the state, it is unrealistic to expect that all blocks can be surveyed to completion (see Block Completion). Therefore, 799 of the blocks across the state were classified as priority blocks and given primary emphasis for surveying. Priority blocks consisted of the southeastern block within each quadrangle. When that block fell outside of Virginia, an alternate was designated as the priority block for the quadrangle. The same priority blocks were targeted for survey during the First Atlas.

Atlas Coordinator

An Atlas Coordinator (Ashley Peele) was hired to guide the data collection efforts carried out by volunteers. In this role, the Coordinator updated and refined the Atlas protocols, led the development of an Atlas Block Explorer tool (see Block Ownership), recruited and trained volunteers, managed the development and distribution of outreach materials, delivered presentations to multiple bird clubs, and coordinated and oversaw the efforts of the Regional Coordinators (see below). Additionally, she courted dozens of partner organizations to contribute volunteer time, expertise, and/or supplemental resources, including free Atlas website hosting and development assistance from the Appalachian Mountains Joint Venture. As the face of the Atlas, the Coordinator was critical to its success by recruiting and motivating a volunteer workforce and guiding their efforts to maximize survey coverage across the state.

Regional Coordinators

The Atlas block grid was organized into 12 regions (Figure 1), each overseen by one to two Regional Coordinators (see Acknowledgments). These were volunteers tasked with coordinating data collection by Atlas volunteers within their region. The Coordinators supplemented the work of the Atlas Coordinator but at a smaller geographic scale. In addition, Regional Coordinators managed block ownership requests (see Atlas Guidelines), tracked progress toward completion of “owned” blocks, and provided support to volunteers. Many of the Regional Coordinators also conducted extensive surveys of blocks themselves. Three regions had co-coordinators, and one region was coordinated by a small number of volunteers working together.

Atlas Guidelines

A block is the survey unit for the Atlas. Although data were reported for individual locations within blocks, all data and survey effort were aggregated and tracked for each block through the Virginia Atlas eBird portal (see Data Platforms). Surveys within a block were conducted during daytime hours. Volunteers were also encouraged to survey blocks between dusk and dawn to document crepuscular/nocturnal species that tend to be active during those periods, such as owls and nightjars.

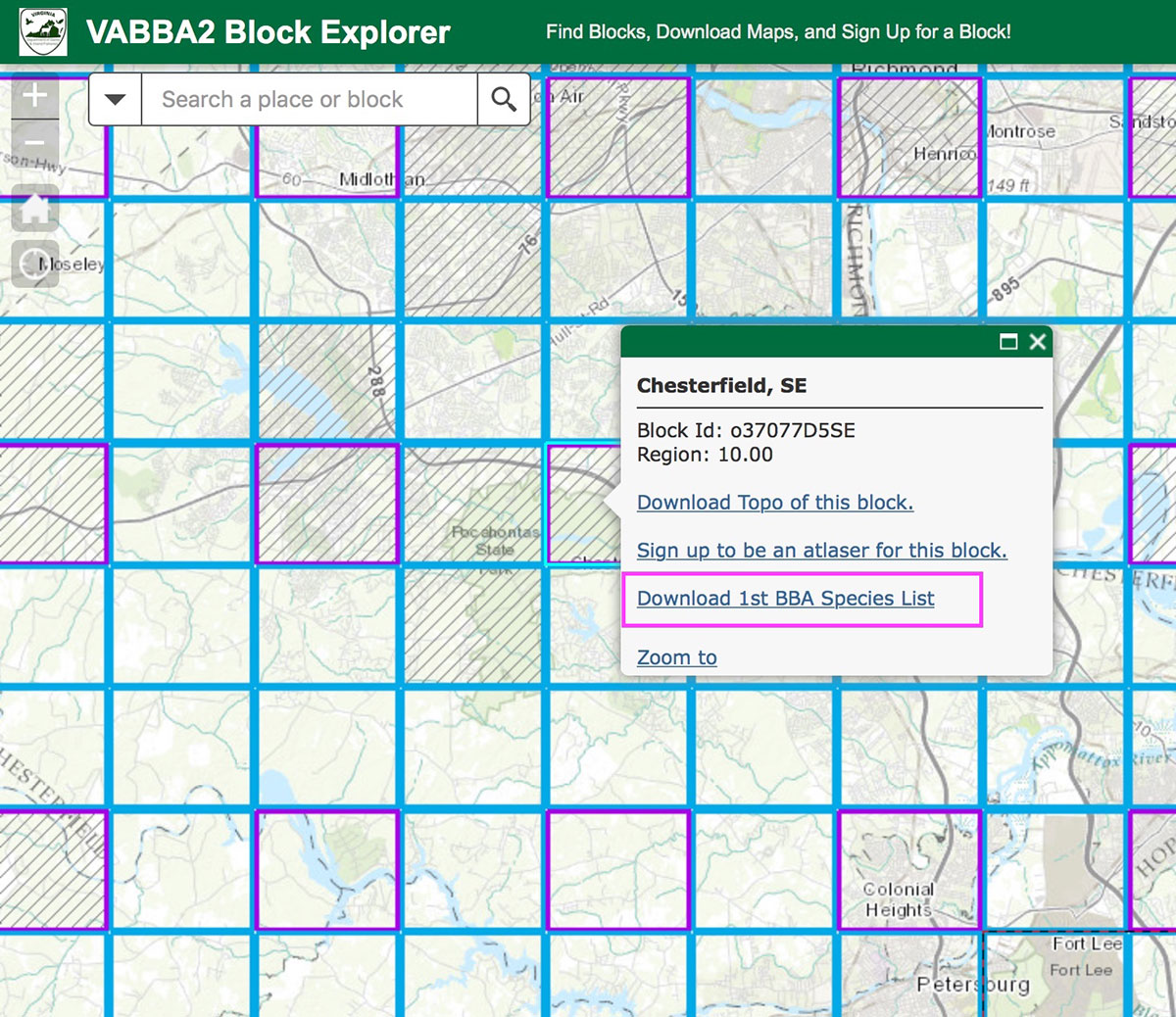

Block Ownership: During the First Atlas, individual blocks were primarily surveyed by one individual who claimed ownership of that block (i.e., responsibility for surveying a block). This process was facilitated during the Second Atlas through an online Atlas Block Explorer tool. The tool was developed by the Atlas Coordinator and VDWR staff with hosting by VDWR to allow volunteers to claim block ownership by signing up for a block. This approach was intended to enable efficient distribution of survey effort such that owned blocks would not receive excessive effort that could have been better directed toward other blocks (see Block Coverage and Distribution of Survey Effort). However, the tool allowed more than one individual to sign up for a block and did not preclude individuals who did not sign up from surveying that block. This flexibility ensured that owned blocks did not end up being under-surveyed.

Breeding Categories and Breeding Codes: The objectives of the surveys were to document the bird species encountered within a block and assign the highest breeding category to each. Breeding categories include observed, possible, probable, and confirmed and indicate the level of certainty that a species is breeding within a block. The categories are based on behaviors and breeding evidence observed in the field, which are designated by standardized breeding codes (Table 1). More detailed descriptions of these breeding codes and guidance on their applicability to particular species were communicated to volunteers via The 2nd Virginia Breeding Bird Atlas Handbook and Guidelines. If multiple behaviors/lines of breeding evidence were recorded for a species at a location on a particular date, then the code corresponding to the highest breeding category was reported. Ultimately, breeding codes and categories were aggregated for each block, and each species detected within a block was assigned the highest breeding category reported.

Breeding codes were consistent with those used during the First Atlas, with the following exceptions:

- Observed was coded as O in the First Atlas;

- The F code was added to the Second Atlas;

- Singing Male was designated by the X code in the First Atlas, and Singing Male present seven or more days by S; and

- The First Atlas included the code PY*, which indicated that “precocial young” were seen.

*Precocial young are flightless young (born with down and able to move about when first hatched) that are restricted to the nest area by dependence on adults of limited in mobility.

Table 1. Breeding Categories and Codes used in the Second Atlas.

| Category | Code | Description | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Null | Coded as ‘observed’ in eBird | A species (male or female) seen during its breeding season, but no evidence of breeding. |

| F | Flyover | Birds observed flying overhead, but never landing within sight. | |

| Possible | H | In Appropriate Habitat | Male or female seen in suitable nesting habitat, during its breeding season. |

| S | Singing Male | A singing male in suitable nesting habitat during its breeding season. | |

| Probable | P | Pair in suitable habitat | Use this code when confident that you have observed a mated pair. |

| S7 | Singing Male present 7+ days | A male is observed singing in same location on at least 2 occasions 7+ days apart | |

| T | Territorial Defense | A permanent territory is presumed through observation of defensive behavior. | |

| C | Courtship Display or Copulation | This can include observations of food transfer, male displays, or grooming between a pair. | |

| N | Probable Nest Site | When a bird is observed repeatedly visiting a potential nest site. | |

| A | Agitated Behavior | Should be used when agitated behavior or anxiety calls are observed from an adult. | |

| B | Nest Building or Repeat Visits | By wrens, kingfishers, woodpeckers, chickadees, and titmouse. All may use multiple cavities/nests. | |

| Confirmed | CN | Carrying Nest Material | Individual(s) observed carrying sticks or other material for nest building. |

| NB | Nest Building | Observation of actual nest construction by species other than those listed for ‘B’ code. | |

| PE | Physiological Evidence | To be used only by experienced bird banders, when a bird is in hand. | |

| DD | Distraction Display | When an adult feigns injury or attacks an intruder to distract from unseen nest or young. | |

| UN | Used Nest | When an occupied nest or eggshells are found, but no adults are present. | |

| FL | Recently Fledged Young | Juvenile birds that are still dependent on parents for food (includes both altricial and precocial young). | |

| ON | Occupied Nest | Adult seen perched on a nest or entering/leaving a nest site in circumstances indicating an occupied nest. | |

| CF | Carrying Food | Adult carrying food for juvenile bird(s). Look for repeated carrying in same direction. | |

| FY | Feeding Young | Adult bird feeding recently fledged young that are not yet independent. | |

| FS | Carrying Fecal Sac | Adult bird carrying a membranous, white fecal sac away from the nest. | |

| NE | Nest with Eggs | Nest with eggs or eggshells on ground observed. Only use this code if adult bird is present to verify species identity. | |

| NY | Nest with Young | Nest observed with young either seen or heard. |

Guidance Regarding Breeding Timelines: In the absence of tangible evidence to confirm breeding, it can be difficult to infer whether a species documented within a block is indeed breeding within that block or is migrating through to more northerly breeding grounds, as there is overlap in the timing of the two. Southward migration in the post-breeding season poses similar challenges. To account for this, Atlases traditionally employ what are known as “safe dates.” These indicate, on a species-by-species basis, the times of year when a species is known to breed within a state outside of the migration window such that it can be reliably considered a breeder. Safe dates were presented and adhered to during the First Atlas. The Second Atlas used a more flexible approach that accounted for potential differences in the timing of breeding for individual species since the last Atlas. Breeding timeline charts were generated to assist observers in assigning breeding codes to their bird observations. One chart was created for each of Virginia’s three major physiographic regions (Coastal Plain, Piedmont, and Mountains and Valleys), based mostly on information compiled by Rottenborn and Brinkley (2007) and on individual species accounts in the Birds of the World series. Each chart shows the typical start date and length of the breeding, migration, and non-breeding seasons, as well as transitional times, for Virginia’s breeding birds. Breeding code adjustments related to breeding timelines were made during the data review process. They were based on an evaluation of the data submitted and recognition that breeding phenologies (timelines) have changed over the last 40 years.

Block Coverage and Distribution of Survey Effort

Throughout the five years of data collection, the Atlas Coordinator worked with volunteers to distribute survey effort as evenly as possible across priority blocks and across Atlas regions. This is important, given the positive relationship between survey effort and the number of species with breeding evidence detected in a block. Species occupancy models like those developed for this Atlas can help account for uneven survey effort. However, consistency in the spatial distribution of survey effort also helps ensure that all of the diverse habitat types spread across the Commonwealth are sufficiently sampled. The challenges in achieving even distribution of survey effort are primarily based on the distribution of birders across Virginia. Less populated regions and geographic areas have fewer birders; thus, blocks there tend to be under-surveyed. Conversely, more populated regions and geographic areas with many more birders tend to see over-surveying of blocks. Different strategies were used to compensate for this.

General and Strategic Guidance: The Atlas Coordinator provided guidance to Atlas volunteers through presentations, in-person and online training, and articles posted on the Atlas eBird portal. Volunteers were consistently encouraged to survey priority blocks until all had been covered in their Atlas region (see Block Completion), prior to surveying non-priority blocks. The Coordinator tracked cumulative survey effort across the state and in individual regions and tailored her annual communication strategies to address geographic gaps in block coverage. For example, volunteers were encouraged to focus survey efforts on shrubland habitats in southwestern Virginia and south-central Piedmont in 2019.

Block Completion: Atlas volunteers were encouraged to survey a priority block until that block was considered complete (i.e., had received sufficient survey effort such that additional effort was unlikely to yield documentation of a significant number of additional species). This approach was implemented to prevent over-surveying blocks and to instead direct survey effort to priority blocks that were not yet complete. It also set a minimum survey benchmark for individual blocks to minimize the number of blocks receiving insufficient survey effort. The following criteria for the completion of individual blocks were established:

- A minimum of 20 and no more than 40 survey hours spread over multiple visits,

- All accessible habitat types present have been visited,

- Surveys are conducted at different times of the year (primarily spring through late summer) to document early and late breeding species,

- At least two night visits to document nocturnal/crepuscular species such as owls and nightjars (any time between 20 minutes after sunset and 40 minutes before sunrise), and

- At least 50% of species detected are confirmed as breeding.

Blockbusting: This refers to the practice of surveying one or more priority blocks over the course of several days or a weekend. Blocks targeted for this strategy are typically located in rural areas with few to no local volunteers and had no breeding bird data. Multiple approaches to blockbusting were taken:

- Field technicians were hired to work primarily on the Atlas point counts;

- Four blockbusting rallies were carried out and led by the Atlas Coordinator at state parks in 2019 (Twin Lakes, Natural Tunnel, Staunton River, and Hungry Mother), and two were conducted in 2020 (Occoneechee and Natural Tunnel) (two additional rallies scheduled for 2020 were cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic); and

- Volunteers conducted blockbusting within or outside of their home regions with guidance and support from the Atlas Coordinator.

Data Platforms

eBird: In the pre-internet era of the First Atlas, volunteers recorded the highest breeding code they documented for each species in a block on a paper field data card. They then mailed those cards at the end of the field season for transcription into a centralized database. Technological advances in the intervening years have made online data submissions possible, and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s popular eBird app was selected as the data platform for the Second Atlas. Virginia was the second Breeding Bird Atlas project to use eBird as its platform (Wisconsin was the first), and several states have followed suit for their bird atlases. Via a VDWR contract with Cornell, a dedicated Virginia Atlas eBird portal was created for submission of Atlas data by volunteers. Cornell customized the portal to include the Virginia block grid and breeding codes as well as block-level summaries. In keeping with standard eBird data structure, data were submitted as checklists, with each representing observations of species on a particular date and time at a particular location. Data submissions included information on location, survey effort, and biological data (Table 2).

Table 2. eBird Data Fields

- Coordinates (entered manually or chosen on map)

- Location Name

- Observation Date

- Observation Type: stationary, traveling, incidental

- Start Time

- Duration of Observation

- Distance Traveled

- Party Size

- Checklist Comments

- Species Observed

- Number of Individuals

- Age and Sex

- Species Comments

- Breeding Code (Highest)

The eBird platform allowed online data submission through a computer or mobile device, with submissions being viewable in real-time across the globe. Its data summary tools let users track, for each block, total survey effort, species documented, highest breeding category by species, and number of data contributors. Use of eBird also resulted in a better spatial resolution of the observations submitted than that achieved during the First Atlas, which only captured observations at the block level.

Priority Species Database: The Second Atlas identified 47 priority species, including subspecies and hybrids, that were of conservation concern or of interest from an ornithological perspective (Table 3). Because eBird did not allow entry of precise coordinates for species documented using a traveling protocol, a Priority Species Database was created. In addition to supporting entry of site-specific coordinates, it allowed Atlas volunteers to submit habitat information and photos associated with their observations. Given the ease of data submission through eBird, the database was underused and only generated 171 records for 23 species and one hybrid; these were reconciled with existing eBird records.

Table 3. Atlas Priority Species, with asterisks indicating those for which observations were submitted to the Priority Species Database.

- American Bittern

- American Black Duck*

- Common Merganser*

- Hooded Merganser*

- Mississippi Kite*

- Northern Harrier*

- Golden Eagle

- Northern Goshawk

- Ruffed Grouse*

- Northern Bobwhite*

- King Rail*

- Black Rail

- Common Gallinule*

- Spotted Sandpiper*

- Upland Sandpiper

- American Woodcock

- Caspian Tern

- Eurasian Collared-Dove

- Monk Parakeet

- Black-billed Cuckoo*

- American Barn Owl*

- Northern Saw-whet Owl

- Common Nighthawk*

- Red-cockaded Woodpecker

- Yellow-bellied Flycatcher

- Loggerhead Shrike*

- Common Raven*

- Bewick’s Wren

- Blue-winged Warbler*

- Golden-winged Warbler*

- Brewster’s Warbler*

- Lawrence’s Warbler

- Blue-winged x Golden-winged Warbler hybrid

- Nashville Warbler

- Yellow-rumped Warbler*

- Cerulean Warbler*

- Black-throated Green Warbler (waynei subspecies)

- Mourning Warbler*

- Swainson’s Warbler*

- Bachman’s Sparrow

- Henslow’s Sparrow

- Saltmarsh Sparrow

- Vesper Sparrow

- Swamp Sparrow (nigrescens subspecies)

- Dickcissel*

- Bobolink*

- Red Crossbill

Paper forms: Printable field forms were made available to Atlas volunteers for hand-written data collection ahead of data submission via eBird.

Atlas Website

A website was created to complement the Atlas eBird portal. The site included many of the resources described above, including guidelines, instructions, and supporting materials, as well as contact information for the Atlas Coordinator and Regional Coordinators. The site linked to the Atlas Block Explorer (Figure 2) through which volunteers could download and print topographic and aerial PDF maps showing block boundaries. The maps could be uploaded to and viewed on mobile devices via an app that displayed the observer’s location on the map. The Block Explorer tool also provided block-specific lists of species with their breeding categories from the First Atlas.

Figure 2. Detail of Atlas Block Explorer

Data Review

Data submitted through the Atlas eBird portal were downloaded into an Atlas database for review and quality control. These data included stationary checklists with breeding codes submitted through the main eBird portal between 2016 and 2020. The review did not evaluate the validity of individual species observations within the checklists, as this process was conducted by a dedicated eBird review team for Virginia. Instead, the review focused on the correct application of breeding codes and breeding categories based on species-specific considerations, observation dates, and geographic locations. Species that were known not to breed in Virginia and observations that did not meet the requirements for possible, probable, and confirmed breeding code application were removed from the database, unless checklist comments with sufficient justification and/or photographic evidence were provided. Similarly, observations associated with traveling checklists that covered over 6 mi (9.7 km) were also removed unless details were provided. This approach prevented associating species with the wrong block, as checklists that cover longer distances have a higher probability of crossing block boundaries.

Supplementary Data

Natural resource professionals affiliated with various agencies, institutions, and organizations regularly conduct bird surveys during the breeding season in Virginia. These data sets can help fill potential geographic and species-specific gaps in the data collected by Atlas volunteers. For example, some surveys take place in areas to which volunteers may have limited access (e.g., private lands, roadless areas, and barrier islands of the Eastern Shore) or in geographies that are under-surveyed by volunteers. Other surveys target species that may require specialized techniques (e.g., the use of playback) or sustained and systematic effort to detect. The results of some of these surveys were entered directly into the eBird Atlas portal by the entities conducting the surveys (e.g., Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey, VDWR Marsh Bird surveys, and Department of Conservation and Recreation Natural Heritage surveys).

Data from additional bird surveys conducted between 2016 and 2020 were extracted from their original data sets and added to the Atlas data collected by volunteers. Data extraction entailed identifying the blocks in which the surveys took place, assigning breeding codes to the observations, and distilling the data to one record per species per block, corresponding to the highest breeding category for that species within that block. Data were extracted from 26 data sets, including one volunteer-based project (Table 4), resulting in 10,872 records for 150 species and two hybrids (Brewster’s Warbler and unidentified Golden-winged Warbler/Blue-winged Warbler hybrid). The data spanned 907 blocks in 110 of Virginia’s 133 counties and independent cities. Although they comprised only 1.5% of the total records, these data were valuable additions to the Atlas data.

Table 4. Breeding bird data sets mined for additional data

| Project Name | Responsible Entity |

|---|---|

| American Black Duck Breeding Survey | Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources |

| American Woodcock Breeding Observations | Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources and its constitutents |

| Anhinga Breeding Survey | Fort Lee |

| Breeding Bird Surveys at Crow’s Nest Natural Area Preserve | Department of Conservation and Recreation’s Division of Natural Heritage |

| Breeding Bird Surveys at Warm Springs Mountain Preserve | The Nature Conservancy |

| Cerulean Warbler Silvicultural Project: Breeding Bird Survey | Appalachian Mountains Joint Venture |

| Clapper Rail Breeding Survey on the Mattaponi River | West Virginia University |

| Colonial Waterbird Surveys at Fort Wool | Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources |

| Golden-winged Warbler Geolocator Migration Project | Virginia Commonwealth University |

| Golden-winged Warbler/Blue-winged Warbler/Hybrid Surveys | Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources |

| Golden-winged Warbler/Blue-winged Warbler/Hybrid Surveys in Southwest Virginia | Virginia Commonwealth University |

| Grassland Breeding Bird Surveys | Virginia Working Landscapes |

| Grassland Breeding Bird Surveys in western Virginia | West Virginia University |

| Henslow’s Sparrow Survey | Manassas National Battlefield Park |

| Lead Exposure of North American Raptors | West Virginia University |

| Loggerhead Shrike Banding and Monitoring Program | Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources |

| NestWatch | Cornell Lab of Ornithology |

| Peregrine Falcon Monitoring and Management | Center for Conservation Biology at the College of William and Mary |

| Peregrine Falcon Surveys | National Park Service |

| Peregrine Falcon Surveys | Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources |

| Project Prothonotary | Ward Burton Foundation |

| Prothonotary Warbler Nest Box Monitoring | Richmond Audubon Society |

| Red-cockaded Woodpecker Monitoring | Center for Conservation Biology at the College of William and Mary |

| Ruffed Grouse and Wild Turkey Survey | Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources |

| Southern Region Avian Monitoring Point Counts | U.S. Forest Service |

| Understanding Genomic Variation Within Golden-winged and Blue-winged Warblers | Cornell University |

Atlas Point Counts

Species abundance data add a third dimension to species distribution data by informing us of not only where a species occurs but also in what numbers. Like other modern Atlases, the Second Atlas extended beyond the traditional volunteer-based Atlas methodology and collected complementary data on avian abundance across the state.

A block-based point count sampling scheme was developed to include approximately one half of Virginia’s blocks, for a total of 2,448 blocks. These blocks were selected systematically, following a checkerboard pattern across the state with a random selection of the starting block. Points were randomly generated along secondary roads (Figure 3), with the goal of surveying eight points per block. A total of 15,765 individual points were surveyed between 2017 and 2020 in 2,078 blocks. The points included 336 off-road points along dirt roads and trails surveyed in 2020 in blocks without public roads (e.g., on National Forest lands). Not all randomly generated points could be surveyed due to access limitations (e.g., private/gated roads, construction, etc.) and remoteness (e.g., points along the state border), resulting in fewer blocks being surveyed than originally targeted.

Each point was surveyed once during the four-year project period using a five-minute variable radius point count protocol. Point counts began approximately 15 minutes after local sunrise and were completed within four hours of sunrise. Surveys were not conducted during weather conditions likely to reduce bird detectability (e.g., high winds or rain). Each bird detected was assigned to the one-minute time interval (0-4) in which it was first detected. Distance from the survey point to the location where the individual was first detected was recorded using a laser range finder. When possible, sex and age (male, female, or juvenile) were recorded, as well as the number of individual birds in a group. Detection type was also noted (song, call, visual, and flyover). Breeding codes associated with probable and confirmed breeding were recorded, and these observations were submitted to the Atlas eBird portal.

Surveys began in mid-May and ended by early July for most years. Surveys in the Mountains and Valleys region began during the last week of May to avoid recording late migrants. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, point counts in 2020 did not get underway until June and were completed by July 1. Thirty-two different field technicians carried out point count surveys over the course of the study. Several of those technicians completed multiple seasons of work.

Data were recorded on paper forms in the field and then transferred to an online database created in Survey123. The database was reviewed for accuracy and quality, including data entry errors. The species recorded at each point were reviewed for temporal and spatial outliers (instances where a species appeared out of the known geographic range or breeding season for Virginia).

Literature Cited

Ligi, S. (2019). Birds of Loudoun: A guide based on the 2009-2014 Loudoun County Bird Atlas. Loudoun Wildlife Conservancy. Loudoun, VA, USA. 214 p.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Trollinger, J.B. and K.K. Reay (2001). Breeding Bird Atlas of Virginia 1985-1989. Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Richmond, VA, USA. 219 pages.