Introduction

The Yellow-throated Vireo is a handsome but easily overlooked bird that breeds in tall forest canopies. Its pleasant, husky song and bright coloration set it apart from other members of its family. John James Audubon favored its “slow, careful, and industrious” nature over that of its “petulant, infantile” relative, the White-eyed Vireo (Vireo griseus) (Audubon 1870). The species occurs in a variety of wooded habitats but not typically in forest interiors; its preference for edges and gaps makes it a common sight in towns and parks and along roads (Rodewald and James 2020). Yellow-throated Vireos are migratory, arriving in Virginia in April from their wintering grounds in Central America, South America, and the Caribbean.

Breeding Distribution

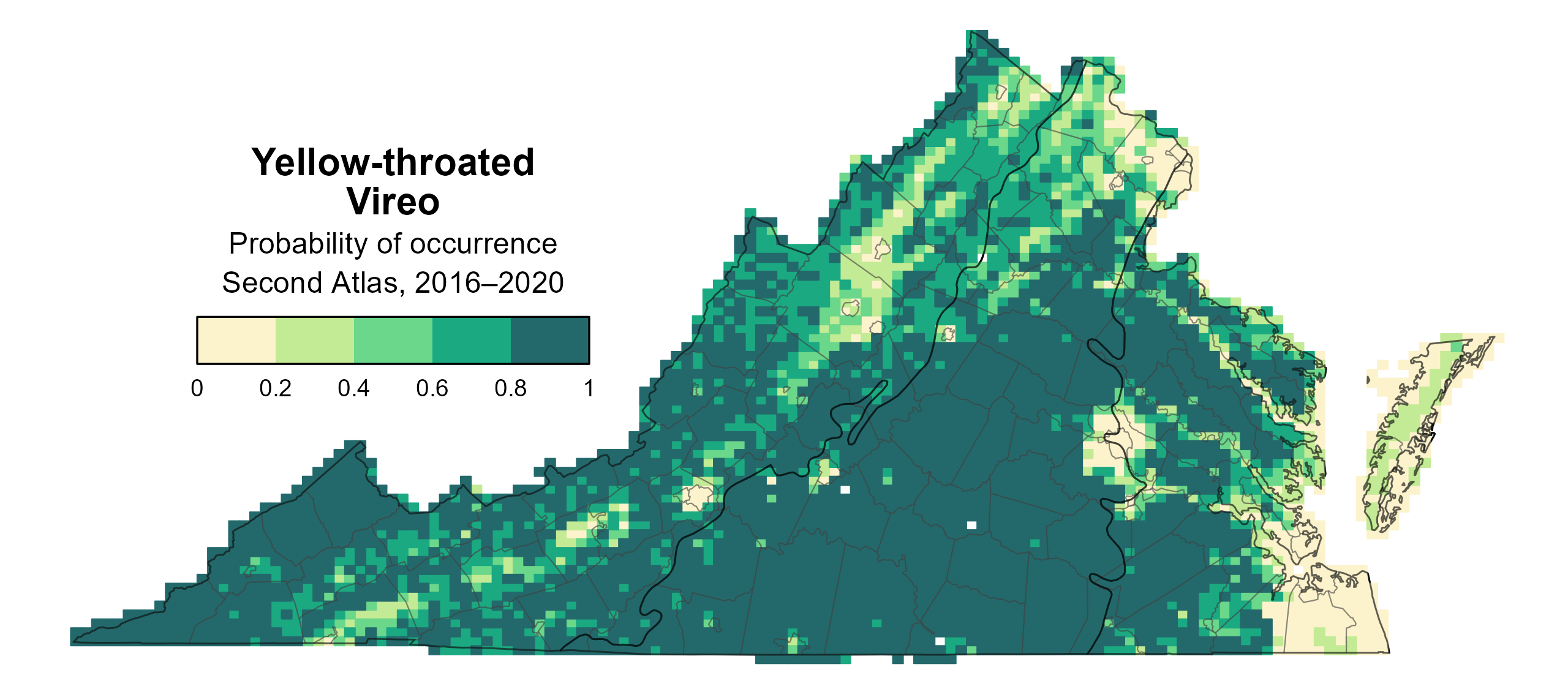

Yellow-throated Vireos are found in all regions of the state, but they are most likely to occur throughout the southern Piedmont region (Figure 1). They are less likely to occur in the southern Shenandoah Valley or in urban areas such as Northern Virginia in the vicinity of Fredericksburg, Hampton Roads, Richmond, Roanoke, Virginia Beach, and Washington, D.C. They are also unlikely to occur in Accomack and Northampton Counties. In general, the likelihood of Yellow-throated Vireos occurring increases in areas with a greater proportion of forest and shrubland and grassland habitats with minimal development. Because the species uses edges and not interiors, they are more likely to occur where the landscape consists of forest that is broken into many smaller patches (Penhollow and Stauffer 2000).

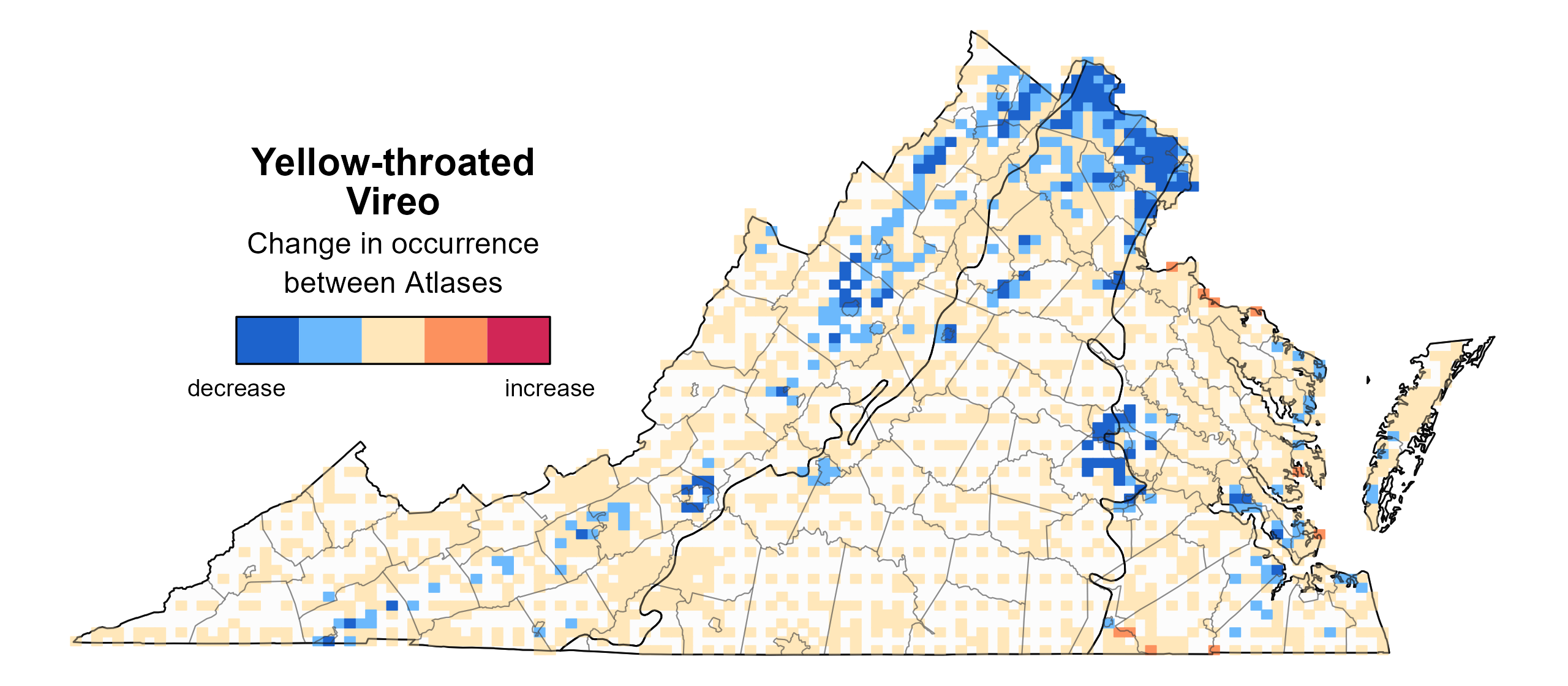

The Yellow-throated Vireo’s probable occurrence in the Second Atlas was mostly similar to that in the First Atlas (Figures 1 and 2). However, there were two notable exceptions. The likelihood of Yellow-throated Vireos occurring around cities, including the metro areas of Richmond and Washington, D.C., decreased, likely because of development. During the time since the First Atlas, extensive development in the broader region of Northern Virginia has drastically increased urban cover (Slonecker et al. 2010). Its likely occurrence also decreased slightly in the Shenandoah Valley; otherwise, it remained stable throughout most of the state.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Yellow-throated Vireo breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Yellow-throated Vireo breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Yellow-throated Vireo change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

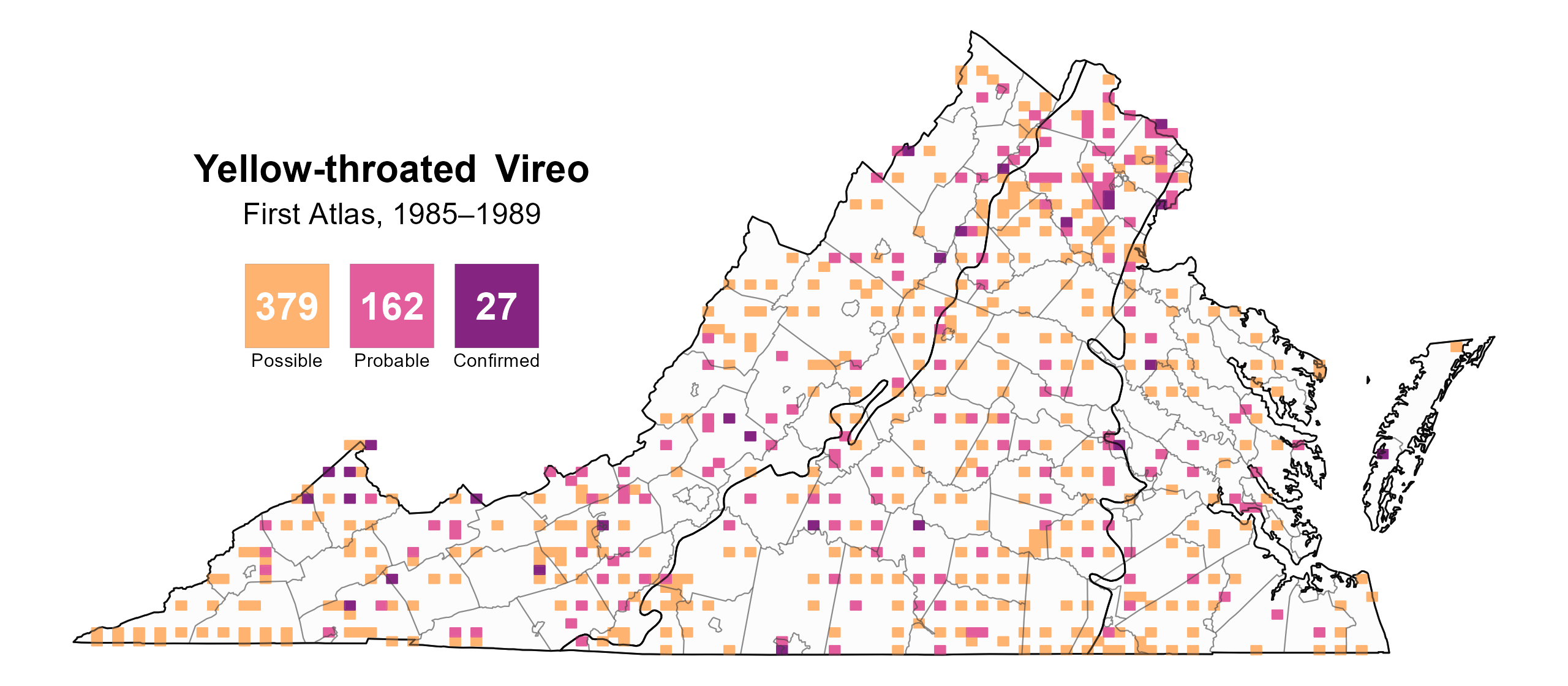

Yellow-throated Vireos were confirmed breeders in 68 blocks and 45 counties and probable breeders in an additional 48 counties (Figure 4). Confirmations were evenly distributed across the Piedmont but were sparse in the northern Mountains and Valleys region. No Yellow-throated Vireos were confirmed breeding on the Eastern Shore or in the vicinity of Hampton Roads-Virginia Beach, although there were a few probable records in the latter. Breeding confirmations were also recorded in all regions of the state during the First Atlas (Figure 5).

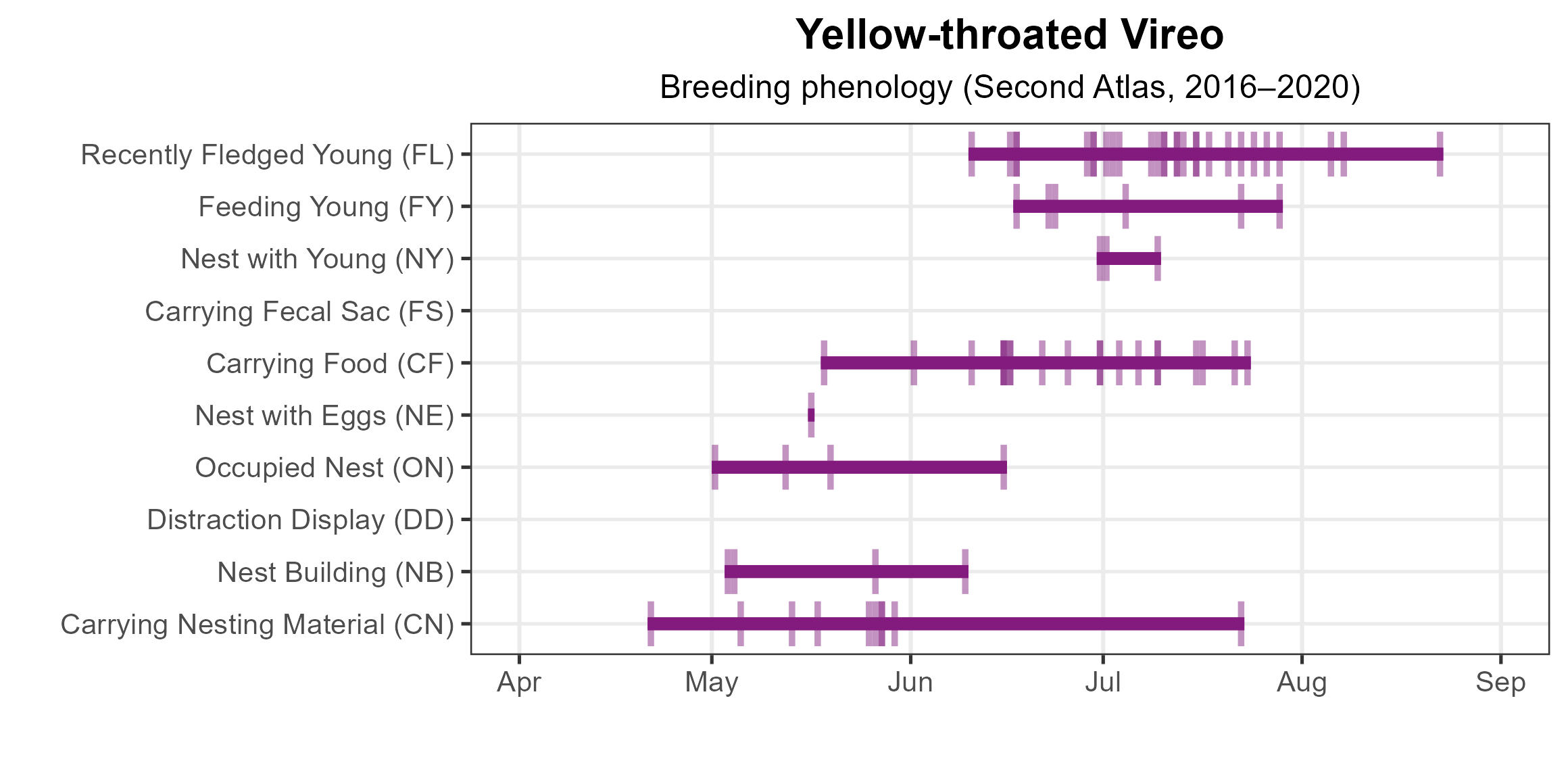

Breeding was confirmed from April 21 (carrying nesting material) to August 22 (recently fledged young) (Figure 6). Observers documented Yellow-throated Vireos performing nearly every type of breeding activity, although the majority of confirmations came from observations of recently fledged young and adults carrying food. Their nests, which are typically located in the crowns of mature deciduous trees (Rodewald and James 2020), proved difficult to find. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Yellow-throated Vireo, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Yellow-throated Vireo breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Yellow-throated Vireo breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Yellow-throated Vireo phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Yellow-throated Vireo relative abundance was estimated to be highest in the southeastern Piedmont region and throughout most of the Coastal Plain region where shrubland and grassland habitats are abundant and the landscape is highly variable (Figure 7). The species was mostly absent or occurred at extremely low-abundance levels in the Shenandoah Valley and urban areas across the state.

The total estimated Yellow-throated Vireo population in the state is approximately 245,000 individuals (with a range between 165,000 and 365,000). Population trends for the species appear stable in Virginia. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) population trend showed a nonsignificant increase of 0.18% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 8). Between Atlas periods, the BBS trend for Virginia was similar, showing a nonsignificant increase of 0.93% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 7: Yellow-throated Vireo relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 8: Yellow-throated Vireo population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Because Yellow-throated Vireo populations are stable, this species is not the focus of any conservation efforts in Virginia. As a family, vireos have done well over the past 60 years, with increasing populations in contrast to other songbirds such as warblers that are declining (Rosenberg et al. 2019).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Audubon, J. J. (1870). The Birds of America. Volume 4. New York, NY, USA.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Penhollow, M. E., and F. Stauffer (2000). Large-scale habitat relationships of neotropical migratory birds in Virginia. The Journal of Wildlife Management 64:362–373. https://doi.org/10.2307/3803234.

Rodewald, P. G. and R. D. James (2020). Yellow-throated Vireo (Vireo flavifrons), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.yetvir.01.

Rosenberg, K. V., A. M. Dokter, P. J. Blancher, J. R. Sauer, A. C. Smith, P. A. Smith, J. C. Stanton, A. Panjabi, L. Helft, M. Parr, and P. P. Marra (2019). Decline of the North American avifauna. Science 366:120–124. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw1313.

Slonecker, T., L. Milheim, and P. Claggett (2010). Landscape indicators and land cover change in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, 1973-2001. GIScience & Remote Sensing 47:163–186.