Introduction

The Tricolored Heron is a graceful, elegant bird with a painterly coloration of slaty blue, purple-chestnut, and clean white. During the breeding season, the bill and lores flush a vibrant blue. This species cuts a striking figure as it dances wildly in shallow water in pursuit of fish. In Virginia, it is a common summer resident of the Coastal Plain, especially near the Chesapeake Bay, but it occurs more sporadically in winter along the outer coast (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007).

Tricolored Herons are colonial nesters, often sharing rookeries with other wading birds. Formerly known as the Louisiana Heron, it was less affected than other species by the plume trade but still experienced declines in the early 20th century (Frederick 2020). Increases through the mid-20th century brought it to Virginia, where it was first documented breeding in 1941 (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007).

Breeding Distribution

The Tricolored Heron was well-covered during the Second Atlas by the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey, a coastal census conducted by the Center for Conservation Biology in collaboration with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources and The Nature Conservancy. The survey identifies nesting locations of this and other species that breed in colonies. Because the Tricolored Heron only breeds within the survey area, there was no need to model its distribution. For information on where the species occurs in Virginia’s Coastal Plain, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

The Tricolored Heron nests exclusively within the survey area covered by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey in 2018, and this survey documented the locations of breeding colonies of this species. Therefore, the species is unlikely to have nested in blocks without confirmed breeding evidence. Additional breeding confirmations were reported by Atlas volunteers in other years of the Second Atlas period.

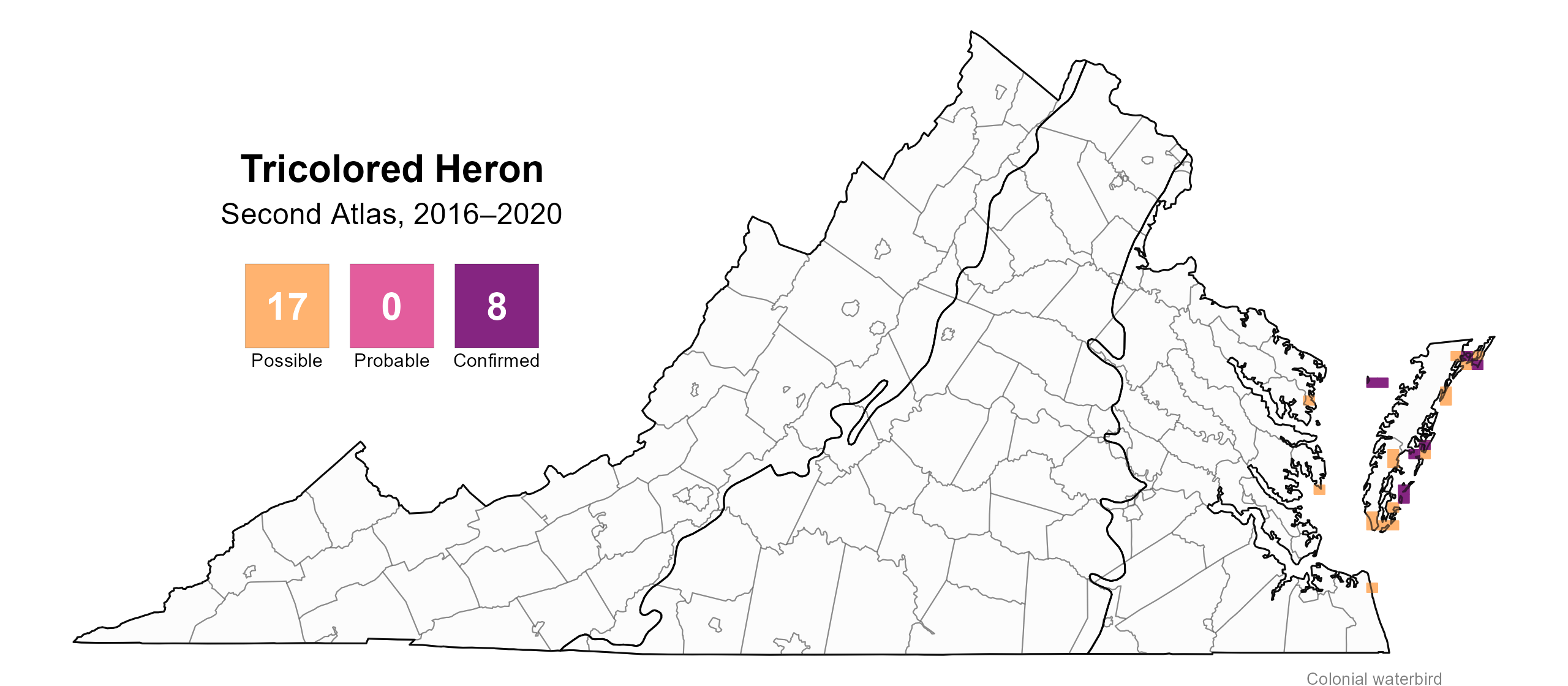

During the Second Atlas, Tricolored Herons bred at a limited number of sites on the Eastern Shore, with confirmed breeding in eight blocks (Figure 1). In Accomack County, nesting occurred bayside at Tangier Harbor and Watts Island, and on the seaward side, it occurred at Chincoteague Causeway, Wire Narrows Marsh, Willis Wharf, and Quinby. In Northampton County, breeding was confirmed at Wreck Island and Cobb Island.

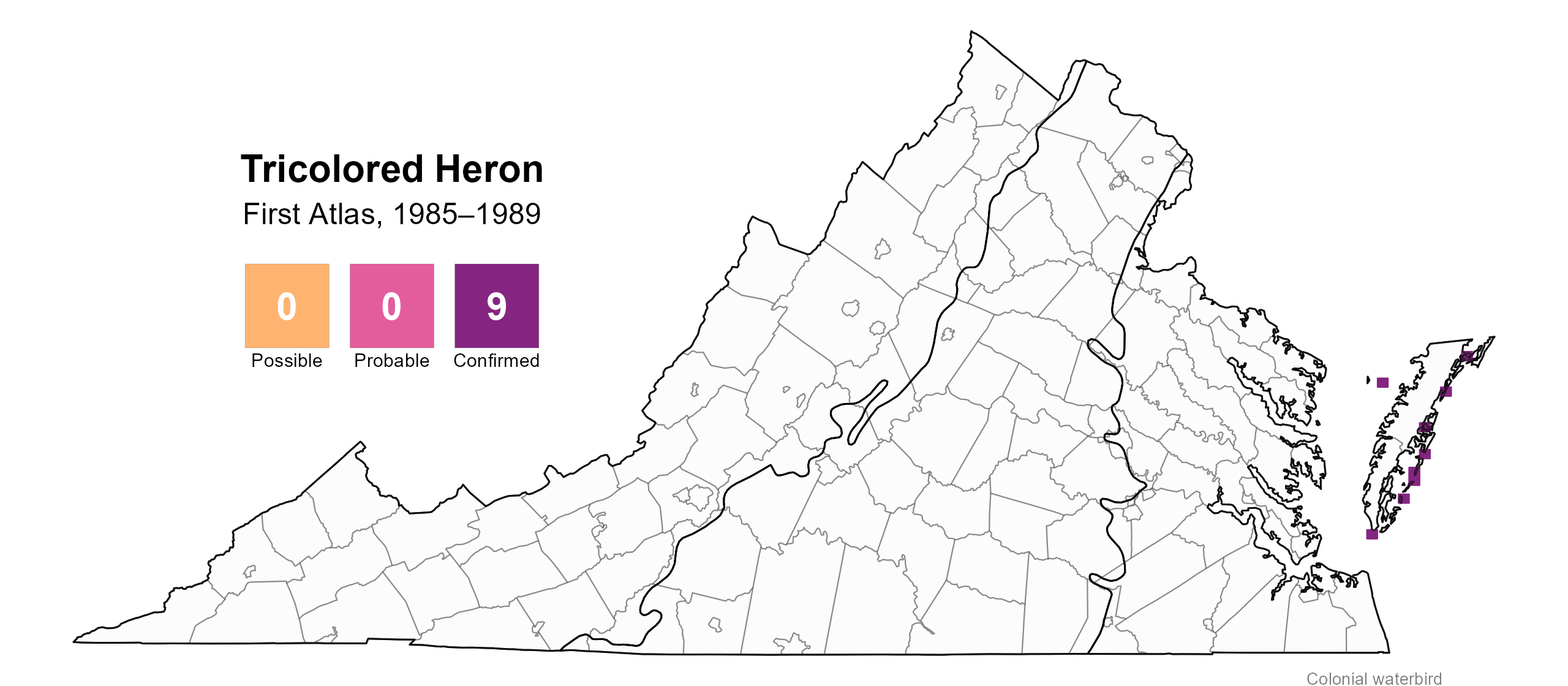

During the First Atlas, breeding was confirmed in nine blocks including Fisherman Island National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) at the southern tip of Northampton County (Figure 2), which was no longer occupied by Tricolored Herons as of the Second Atlas.

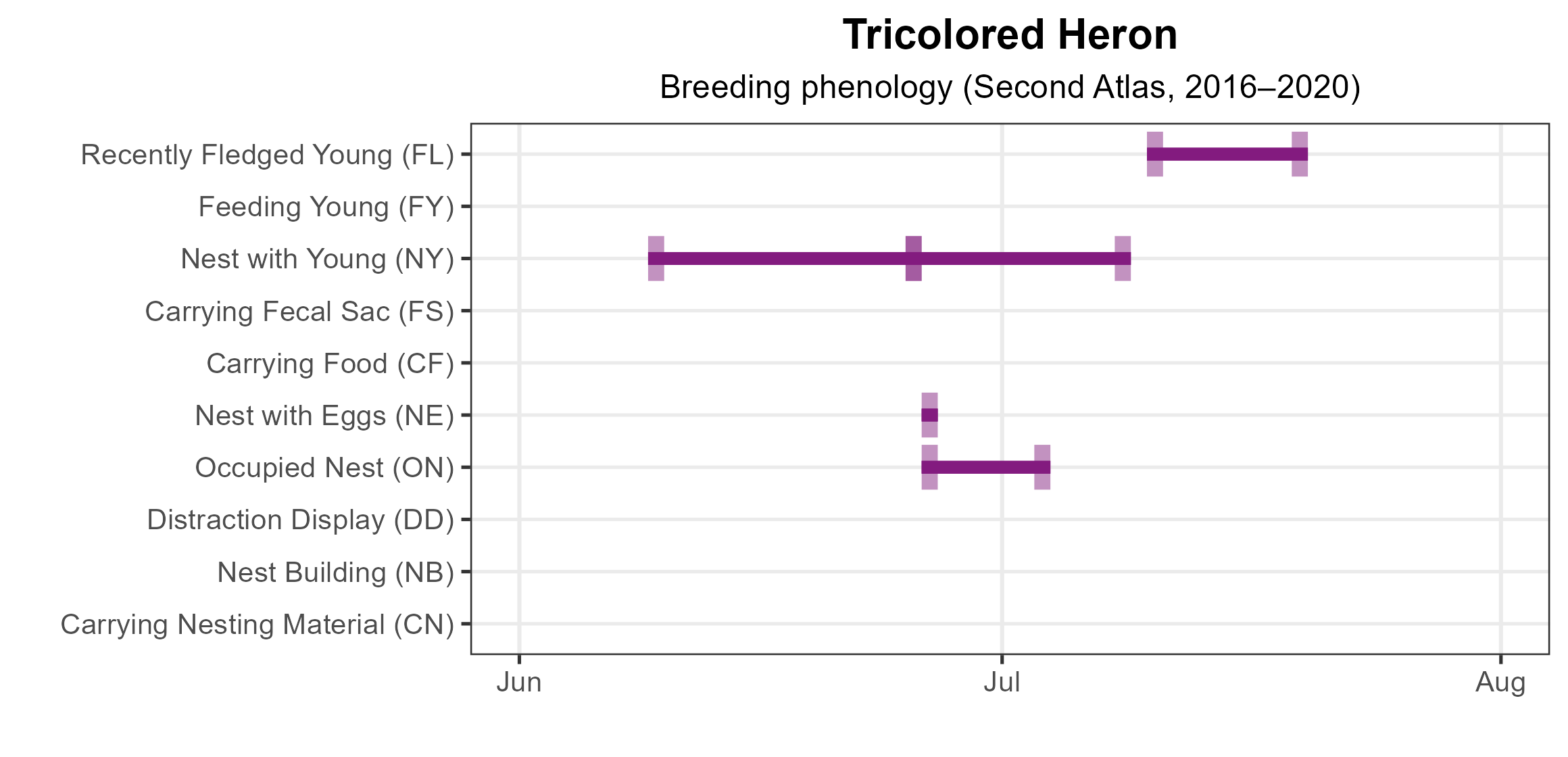

During the Second Atlas, few individual observations of breeding Tricolored Herons were made, limiting our picture of their breeding phenology (Figure 3). They had nests with young from June 25 and were caring for young through early July. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Tricolored Heron, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Tricolored Heron breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category. Nesting is unlikely outside of confirmed blocks.

Figure 2: Tricolored Heron breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Tricolored Heron phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

The Tricolored Heron had too few detections during the Atlas point count surveys to develop an abundance model. However, the distribution and size of Tricolored Heron colonies derived from the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey are displayed on the CCB Mapping Portal.

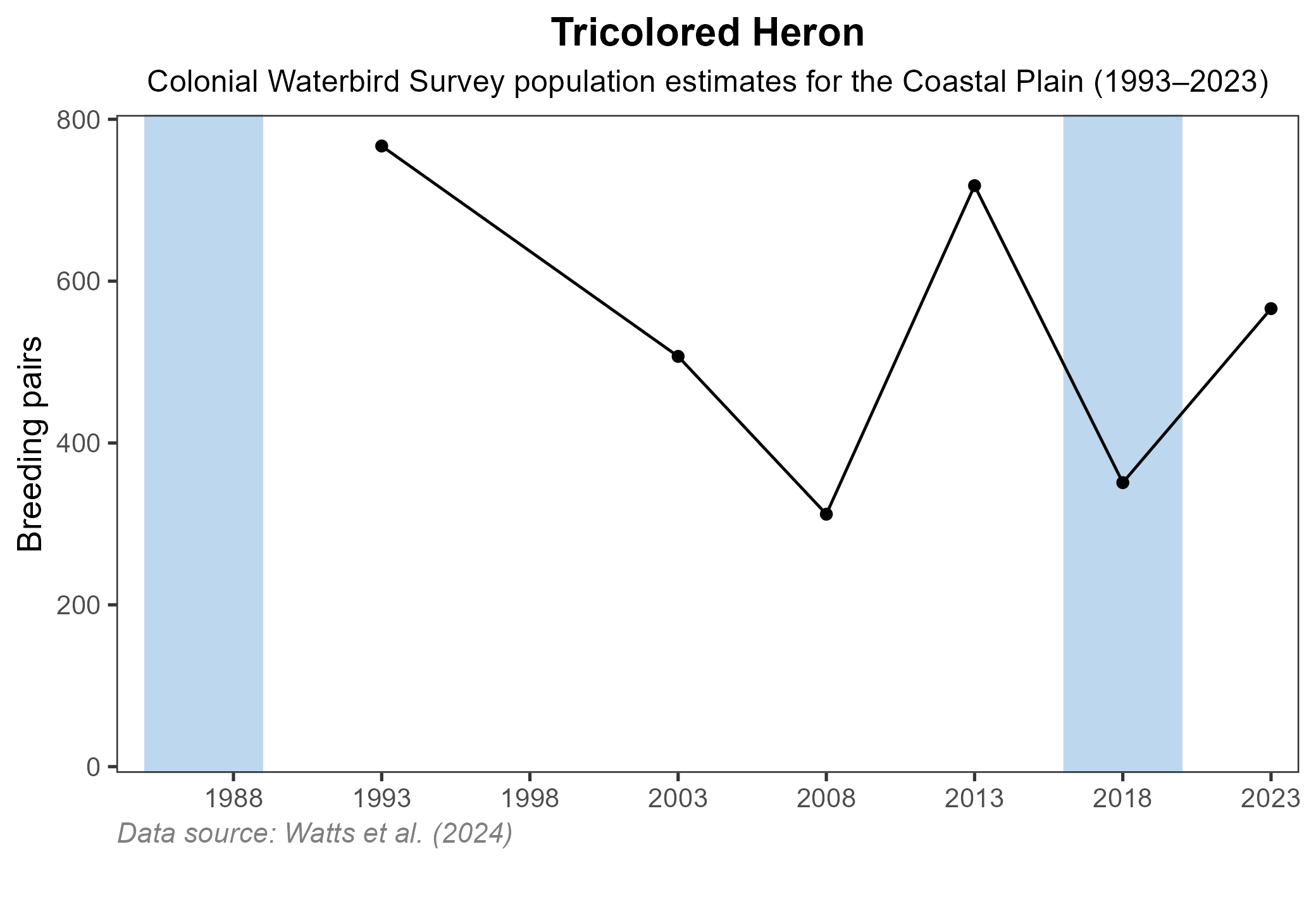

The Virginia Tricolored Heron population increased during the species northward range expansion through the mid-century, apparently reaching a high during the 1950s–1970s. The Virginia Colonial Waterbird Surveys show that populations slumped, particularly on the barrier islands, through the mid-1990s (Watts et al. 2019). Since the Colonial Waterbird Survey was standardized in 1993, populations have fluctuated from a high of 767 pairs in 1993 to a low of 312 in 2008 (Figure 4; Watts et al. 2019; Watts et al. 2024).

Figure 4: Tricolored Heron population trend for Virginia’s Coastal Plain. This chart illustrates the number of breeding pairs as estimated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey (Watts et al. 2024). A data point is not included for 1998, as the Survey covered a smaller geographic area in that year. The vertical light blue bars represent the periods corresponding to the First Atlas (1985–1989) and Second Atlas (2016–2020).

Conservation

The Tricolored Heron is classified by the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan as a Tier II Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Very High Conservation Need). It faces many of the same threats as other colonial waterbirds. These include loss and degradation of breeding habitat due to development, sea-level rise, and erosion of nesting islands (Watts et al. 2019). However, even as many colonial-breeding birds are experiencing population declines, Tricolored Herons appear to be showing signs of recovery (Watts et al. 2024). To support long-term conservation, management should focus on protecting current colony sites, securing future inshore breeding habitat as the sea level rises, and implementing predator control where necessary.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Frederick, P. C. (2020). Tricolored Heron (Egretta tricolor), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.triher.01.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. Boettcher, and A. L. Wilke (2019). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2018 breeding season. CCBTR-19-06. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. Boettcher, and A. L. Wilke (2024). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2023 breeding season. CCBTR-24-12. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA, USA.

.