Introduction

The Seaside Sparrow is known for its enthusiastic but quiet buzzing song that barely stands out over the rustling of reeds. These dusky gray birds with yellow lores are common to abundant migrants and summer and winter residents in Virginia’s salt marshes along the Atlantic and Chesapeake Bay (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). The subspecies in Virginia, A. m. maritimus, can reach high densities in appropriate habitat.

Seaside Sparrows breed farther upstream on tidal rivers than the related Saltmarsh Sparrow (Ammodramus caudacutus). Their preferred habitat is tidal marshland with extensive covering of cordgrass, typically saltmarsh cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), and patches of dead stems to use as song perches. Similar to those of other saltmarsh-breeding songbirds, their nests are constantly at risk of flooding during storms and high spring tides (Greenlaw et al. 2022). The tidal zone experiences constant changes, and Seaside Sparrows can roam within and near their territories to find food on exposed mudflats.

Breeding Distribution

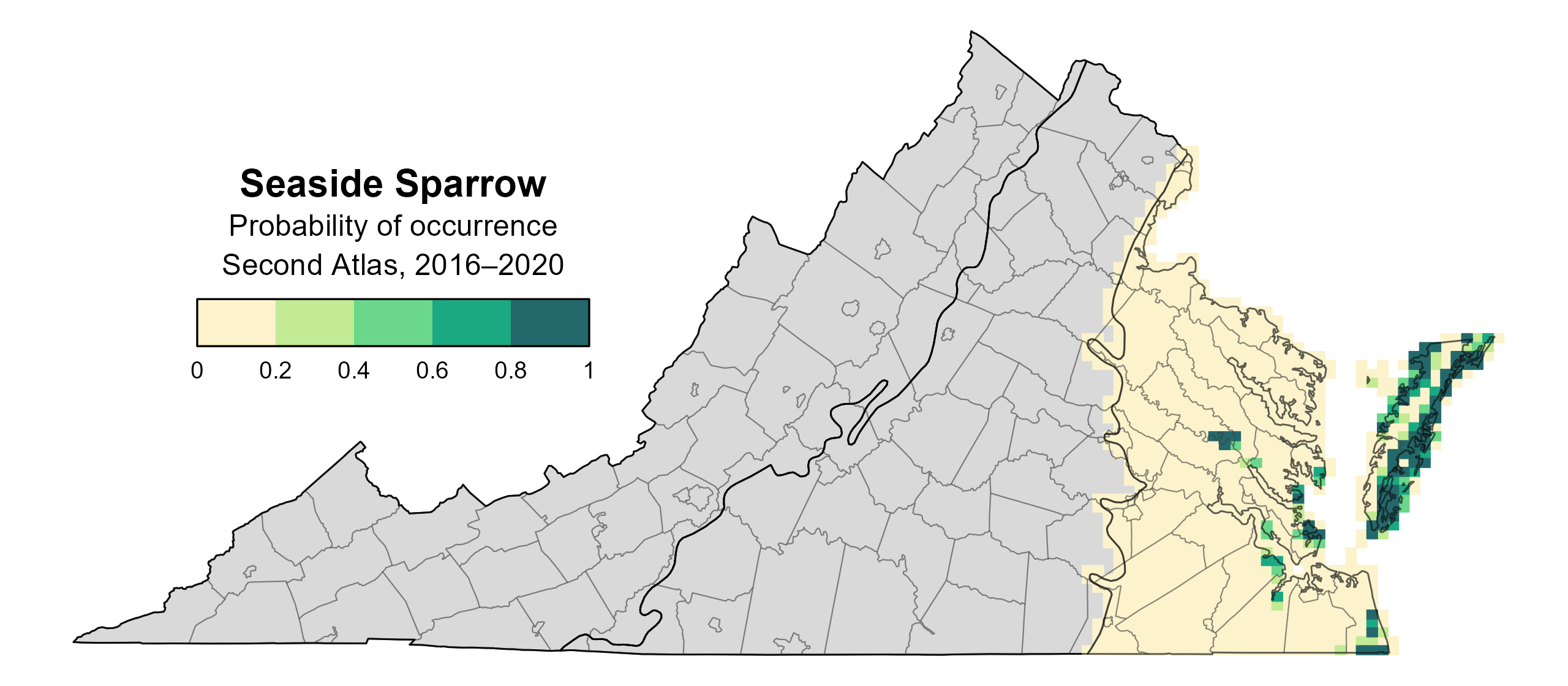

Seaside Sparrows are completely restricted to the Coastal Plain region and are most likely to occur in marshes along the Atlantic and northern Chesapeake Bay portions of the Eastern Shore, as well as in other pockets of extensive marshland along Virginia’s tidal rivers (Figure 1). The likelihood of Seaside Sparrow occurrence increases sharply with the proportion of marsh cover in a block.

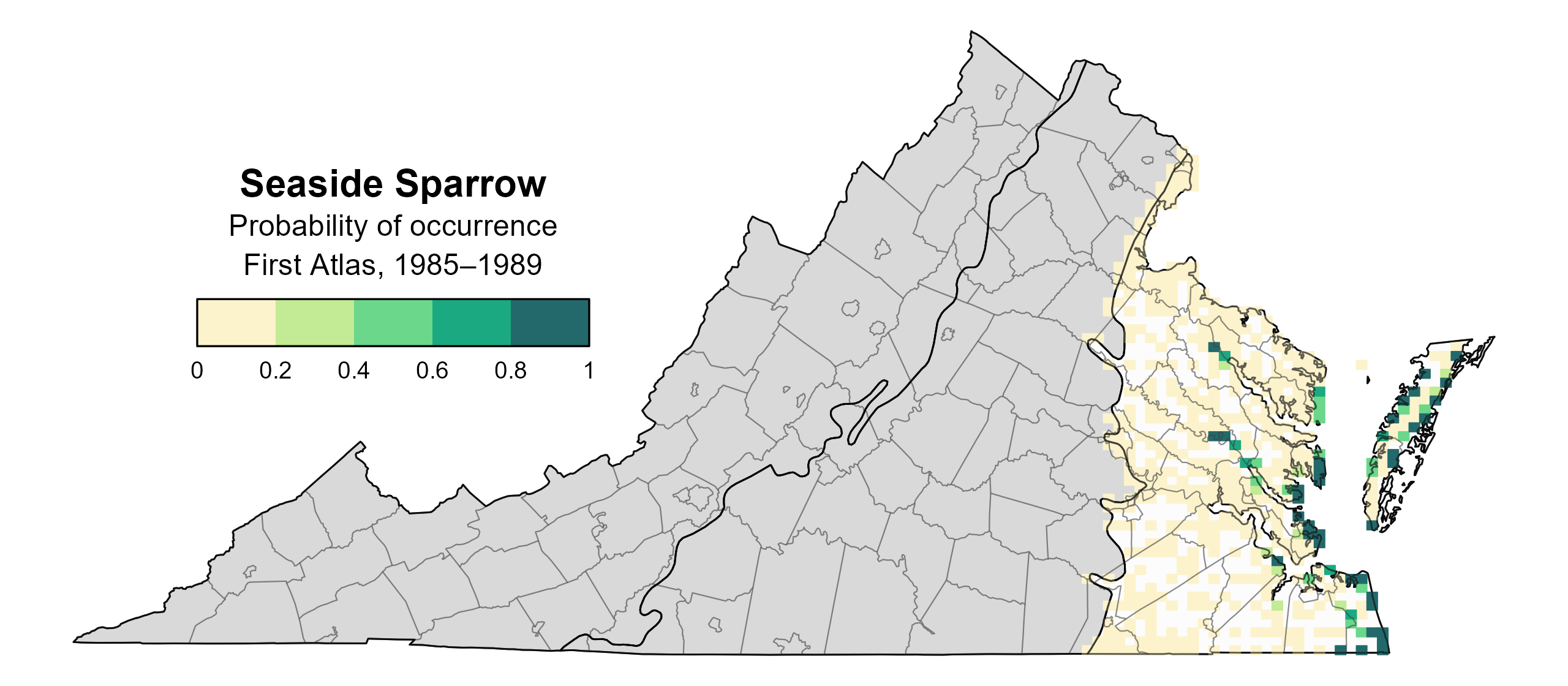

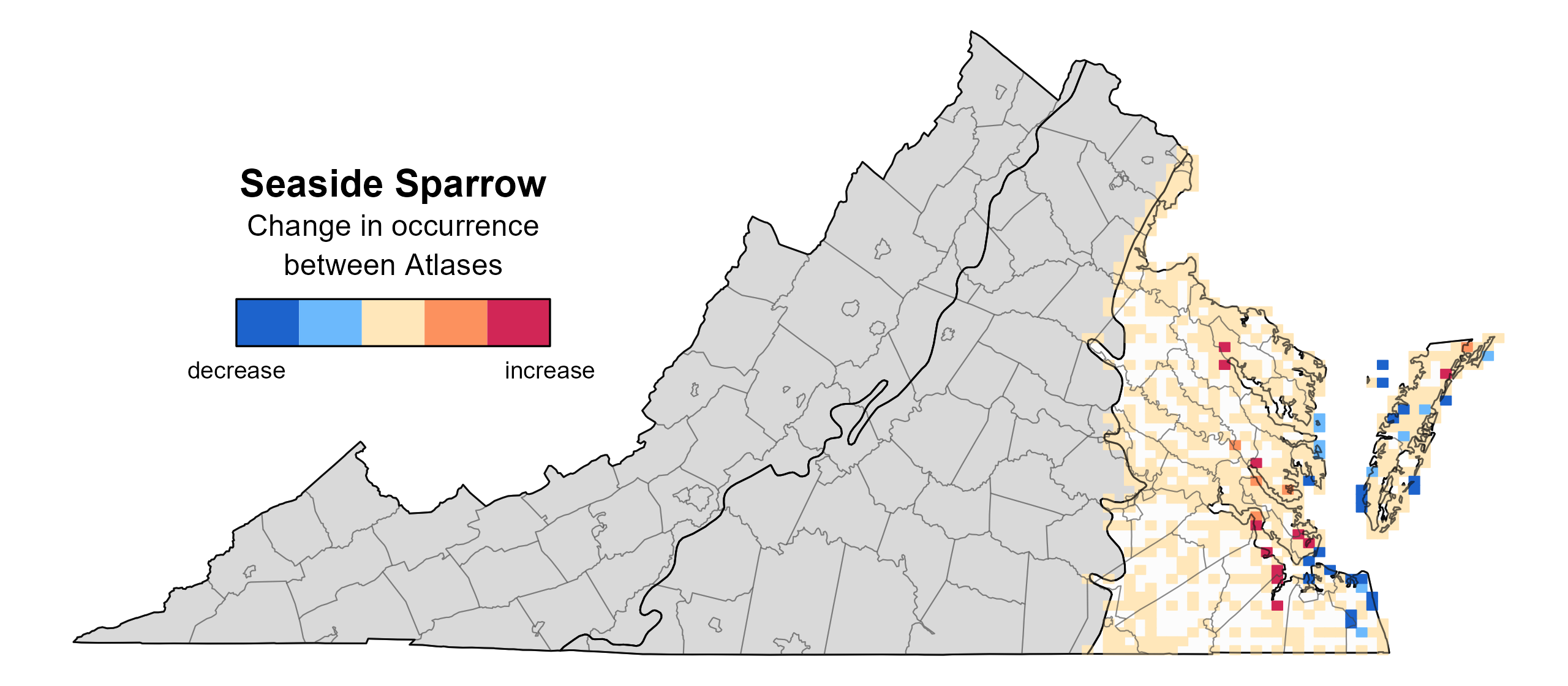

Seaside Sparrow’s likely occurrence in the Second Atlas was largely similar to that of the First Atlas (Figures 1 and 2). However, its likelihood of occurring in the Hampton Roads-Virginia Beach area and in several areas on the Eastern Shore decreased (Figure 3).

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Seaside Sparrow breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 2: Seaside Sparrow breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Seaside Sparrow change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

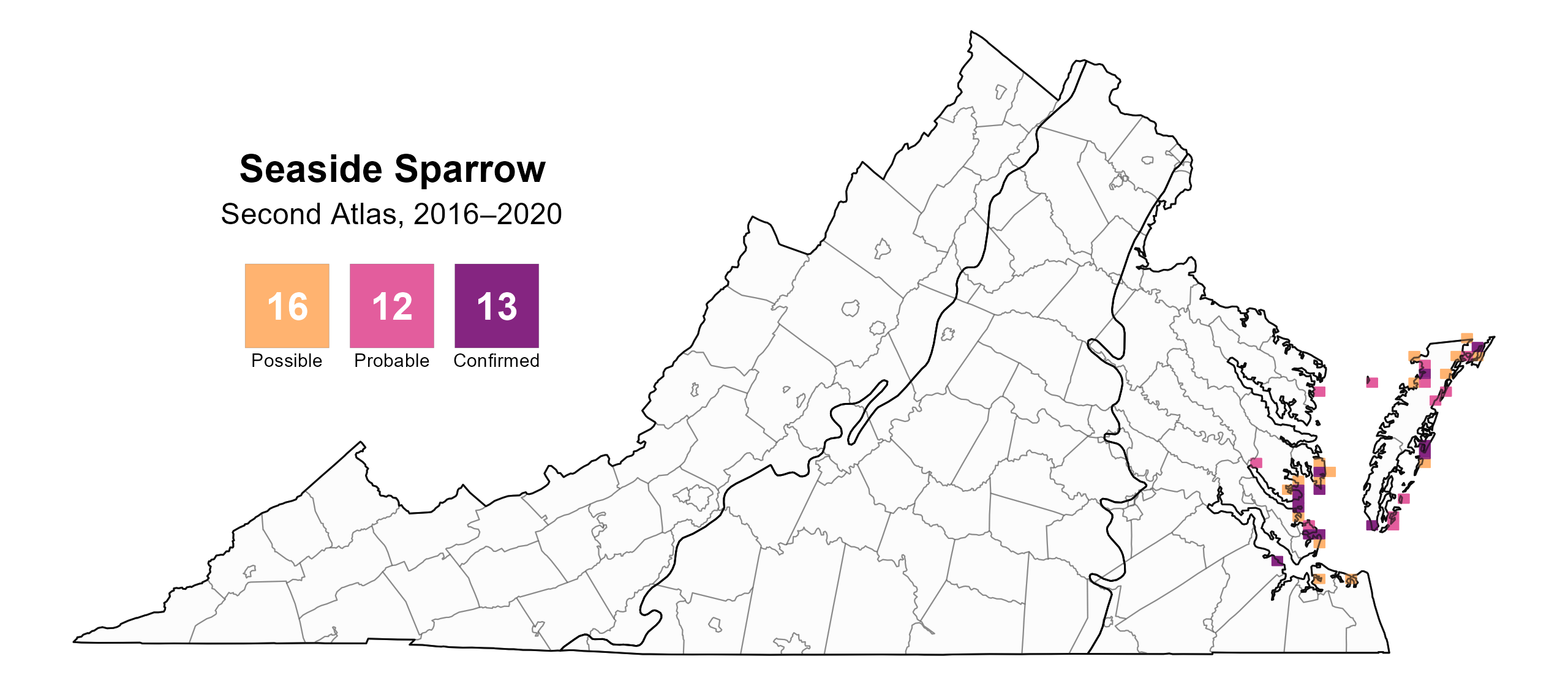

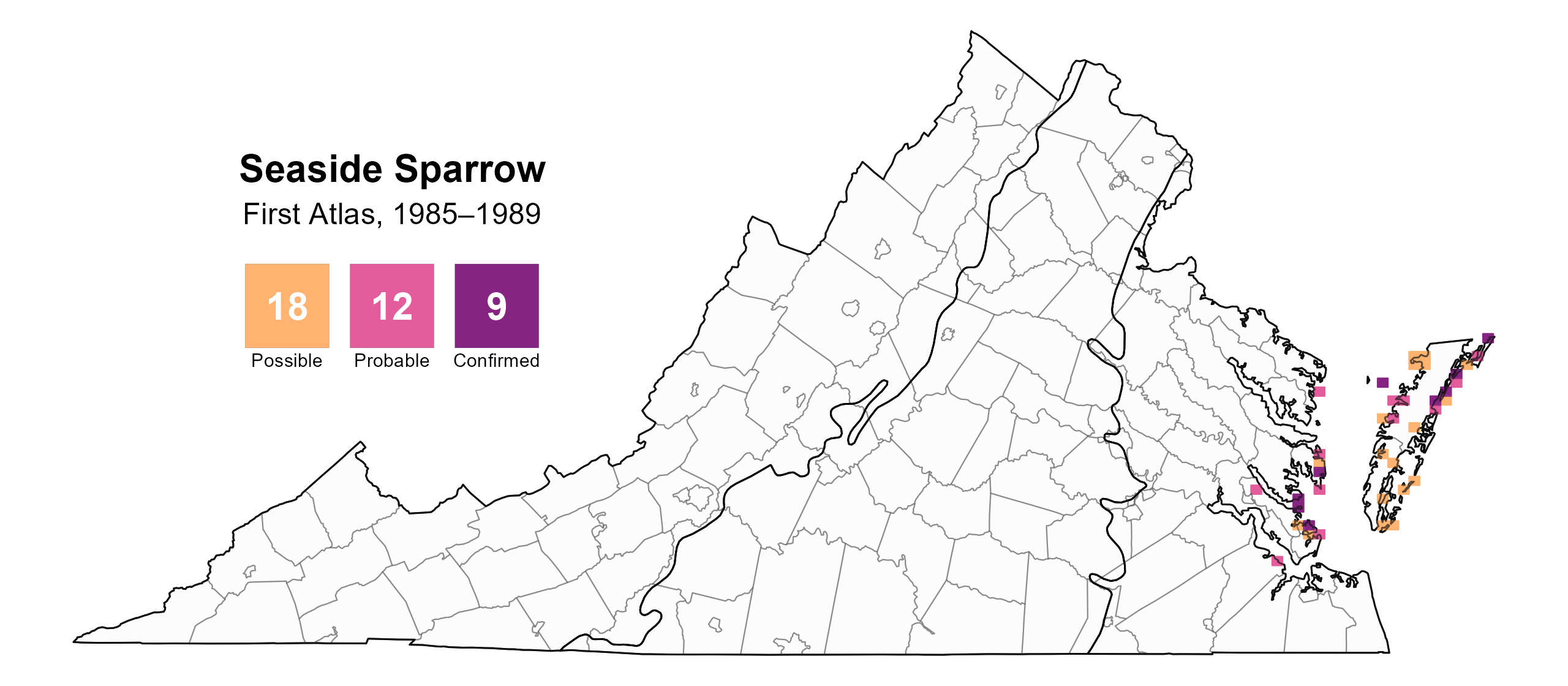

Seaside Sparrows are restricted to the outer Coastal Plain region, and they were confirmed breeders in 13 blocks and eight counties: Accomack, Gloucester, Hampton, Isle of Wight, Matthews, Northampton, Poquoson, and York (Figure 4). Breeding was probable in Northumberland County. Breeding observations were recorded in similar locations during the First Atlas (Figure 5).

Because the species is so seldomly observed, it is difficult to describe their breeding phenology. Marsh-nesting birds are difficult to observe in the nest due to their inaccessible habitat and secretive nature. Most breeding confirmations were of fledglings or adults carrying food. Adult birds were observed already carrying food beginning on May 31, and fledglings were seen through August 10 (Figure 6). For more general information on the breeding habits of the Seaside Sparrow, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Seaside Sparrow breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Seaside Sparrow breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Seaside Sparrow phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Abundance could not be modeled from Atlas point count data because the species is so rare and restricted to hard-to-access coastal habitats. Additionally, the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) does not detect Seaside Sparrows sufficiently often to produce trend estimates for the state. Targeted surveys for marsh birds conducted on the East Coast are the only reliable indicators of Seaside Sparrow population trends. Based on such surveys alongside historical data, Correll et al. (2017) estimated that no trend could be determined for the regional population spanning Maine to Virginia from 1998–2012.

Conservation

Despite apparently stable populations in Virginia, the Seaside Sparrow faces threats, though the situation is more dire in other portions of its range. For example, of the known subspecies, in Florida, the Dusky Seaside Sparrow (Ammospiza maritimus nigrescens) is extinct, and the Cape Sable Seaside Sparrow (A. m. mirabilis) is endangered.

Loss and modification of tidal saltmarsh habitat, including from ditching and draining, are the most serious threats to Seaside Sparrows (Greenlaw et al. 2022). Coastal development can also result in the loss of saltmarsh habitat and impede its migration inland. Sea-level rise and increasing storm events are also likely to accelerate the loss of tidal marshes. Population viability analysis has found that sea-level rise-induced marsh habitat loss will reduce Seaside Sparrow population viability in the upper Chesapeake Bay (Kern and Shriver 2014). Marsh restoration and assisted marsh migration, that is, assisting the normal process of marshland moving upland with rising water levels, could help ensure populations remain viable.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Correll, M. D., W. A. Wiest, T. P. Hodgman, W. G. Shriver, C. S. Elphick, B. J. McGill, K. M. O’Brien, and B. J. Olsen (2017). Predictors of specialist avifaunal decline in coastal marshes. Conservation Biology 31:172–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12797.

Greenlaw, J. S., W. G. Shriver, and W. Post (2022). Seaside Sparrow (Ammospiza maritima), version 2.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald and B. K. Keeney, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.seaspa.02.

Kern, R. A., and W. G. Shriver (2014). Sea level rise and prescribed fire management: implications for Seaside Sparrow population viability. Biological Conservation 173:24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.03.007.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.