Introduction

The Saltmarsh Sparrow is a secretive dweller of hard-to-access marshes, characterized by an orange-and-dusky face and a quiet whisper song. It is rare among songbirds as an obligate tidal-marsh specialist, nesting nowhere else. Its high marsh habitat is dominated by saltmeadow cordgrass (Spartina patens) and rushes such as saltmarsh rush (Juncus gerardii) and black needlerush (Juncus roemerianus) (Wilson et al. 2007; Greenlaw et al. 2020). This species is typically limited to marshes that are greater than 124 acres (50 hectares) and has adapted to the risks of living in a tidal system (Wilson et al. 2007). They place their nests carefully, synchronize breeding to avoid the highest spring tides when their nests are flooded, and even build canopies to prevent eggs from floating away. Females do this as single parents, as the males do not participate in brood rearing (Greenlaw et al. 2020).

In Virginia, this species previously inhabited the Eastern Shore as well as the Western Shore, but by the 1990s, it was almost entirely extirpated from the Western Shore (Watts 2004). The most recent data from the Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) at the College of William and Mary shows that based on 652 survey points on the Eastern Shore, this sparrow only breeds in Accomack County (Hines et al. 2024).

The Saltmarsh Sparrow and Nelson’s Sparrow (Ammospiza nelsoni) were formerly considered one species called the Sharp-tailed Sparrow. In 1995, they were split, with the Saltmarsh Sparrow being awkwardly named Saltmarsh Sharp-tailed Sparrow (Monroe et al. 1995). In 2009, the sharp-tailed epithet was dropped from both, leaving the name it bears today (Chesser et al. 2009).

Breeding Distribution

Because the species is rare, its distribution could not be modeled. For information on where Saltmarsh Sparrows occur in Virginia, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

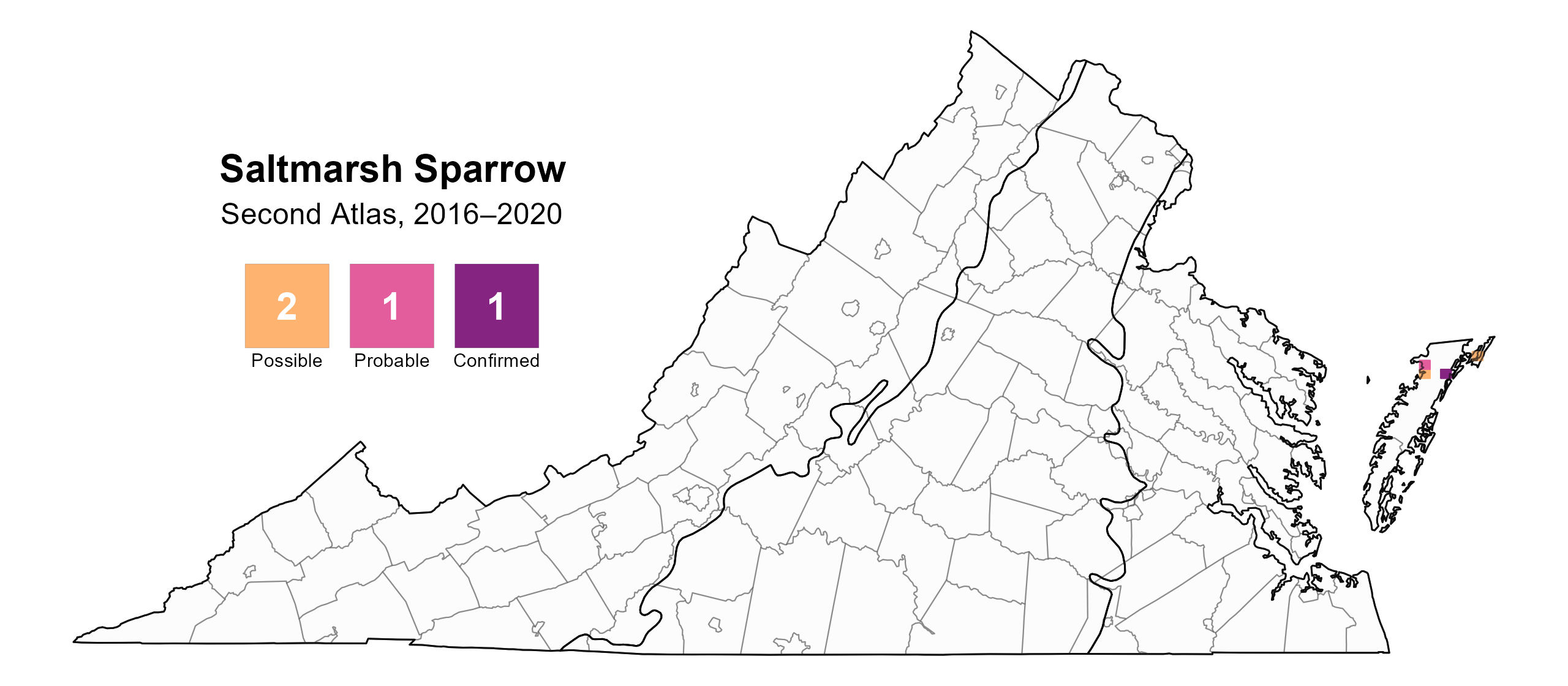

Saltmarsh Sparrows were rare in Virginia during both Atlas periods, restricted to a few select sites in the Coastal Plain region. In the Second Atlas, all breeding records were from Accomack County, including confirmed breeding in a single block and probable breeding in one additional block in Saxis Wildlife Management Area (Figure 1). There were also two records of possible breeders: one singing bird on the Chincoteague South Wash Flats and one individual in bayside marshes along Pocomoke Sound.

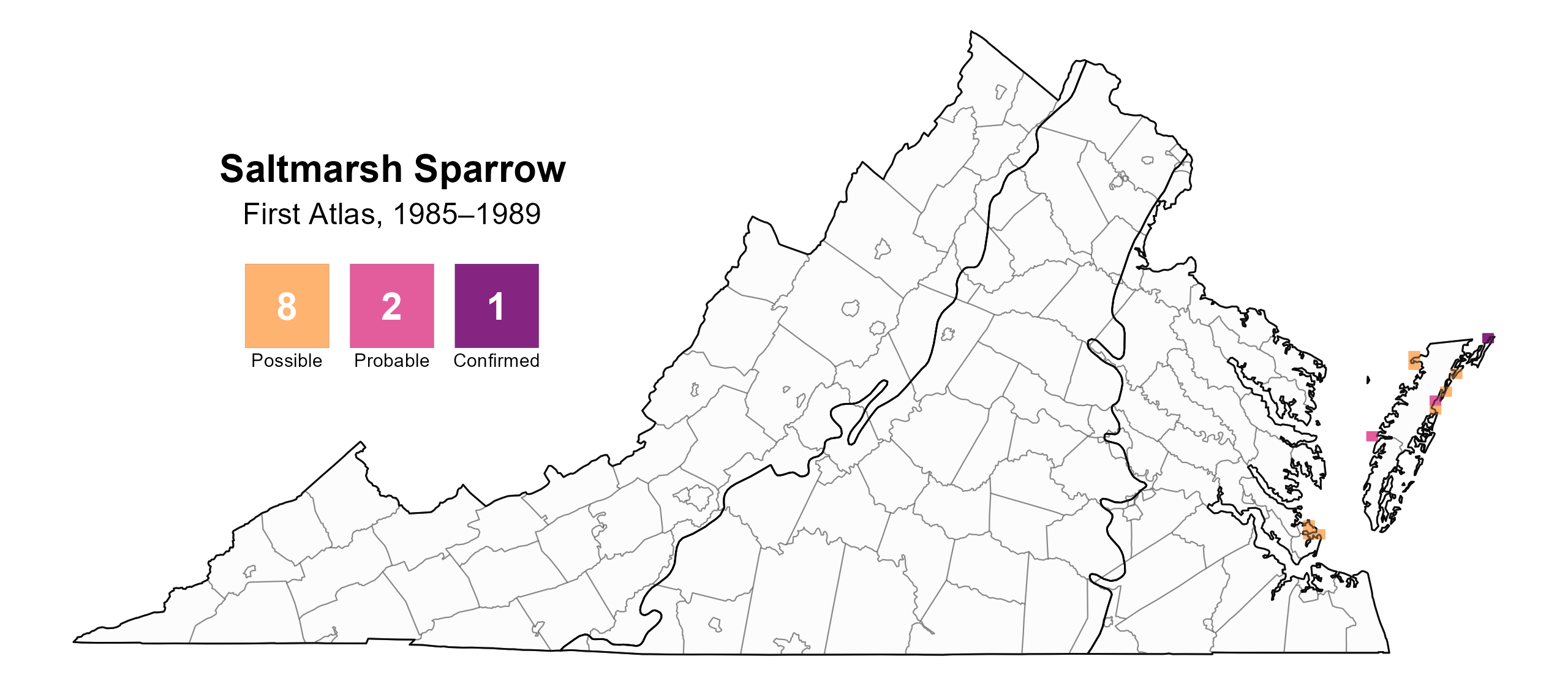

In comparison to the First Atlas, the Second Atlas detected this species in slightly fewer locations (Figures 1 and 2). As populations have declined (see Population Status) between Atlas periods, it is possible that the species has become even harder to detect during the breeding season.

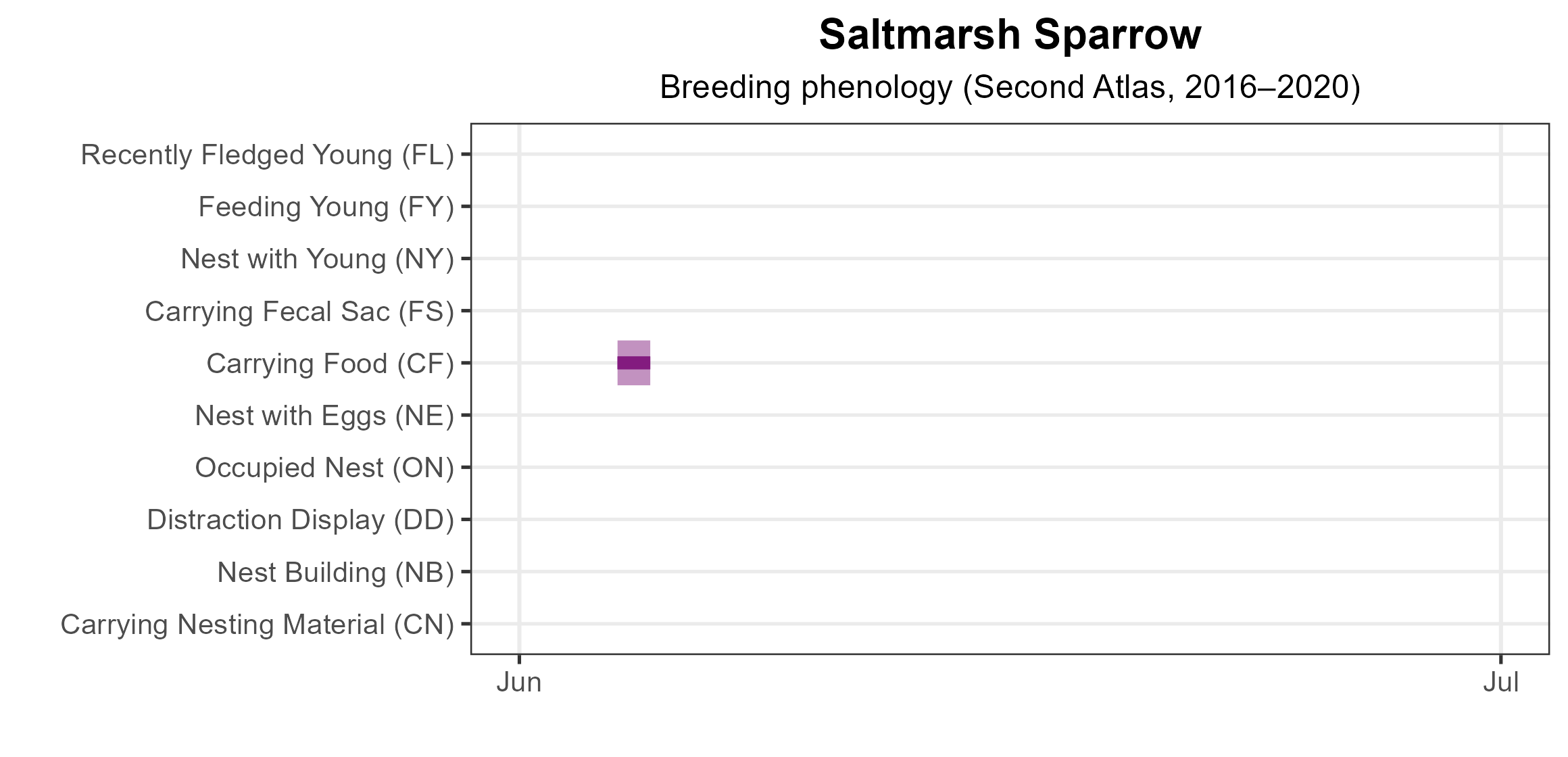

Phenology was not accurately captured because there was only one confirmation of a bird carrying food on June 4 (Figure 3). For more general information on the breeding habits of the Saltmarsh Sparrow, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Saltmarsh Sparrow breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Saltmarsh Sparrow breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Saltmarsh Sparrow phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Abundance could not be modeled from Atlas point count surveys because the species is so rare. Targeted surveys for marsh birds conducted on the East Coast are the only reliable indicators of Saltmarsh Sparrow population trends. Based on such surveys alongside historical data, Correll et al. (2017) estimated that the regional population spanning Maine to Virginia experienced a significant decline of nine percent per year from 1998–2012.

Conservation

This species, like many other marsh-dwelling birds, is threatened by loss and degradation of marsh habitat from coastal development, as well as sea-level rise. Saltmarsh Sparrows are particularly vulnerable to changes in marsh hydrology because they operate on a razor-thin margin of error with high spring tides or storm surges washing away their nests (Center for Biological Diversity 2024). When human-built structures such as dams, ditches, dikes, or causeways interfere with the natural flow of tides in a wetland system, they create a tidal restriction. Research has found that tidal marsh specialist species such as Saltmarsh Sparrows are declining in tidally restricted locations but maintaining their populations in marshes without road crossings (Correll et al. 2017). With current rates of sea-level rise, the species is at serious risk of extinction.

Given its risk in Virginia, the 2025 Wildlife Action Plan includes the Saltmarsh Sparrow as a Tier II (Very High Conservation Need) Species of Greatest Conservation Need (VDWR 2025). It has been petitioned for protection under the Endangered Species Act (Center for Biological Diversity 2024). In Virginia, the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Virginia Tech, and CCB coordinate on Saltmarsh Sparrow conservation efforts. Additionally, the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture considers the top priority marshes to be those on Chincoteague and Assateague Islands, from Chincoteague Bay to Metompkin Island, Cedar and Parramore Island, from Pocomoke Sound to Tobacco Island (including Saxis Marsh), southern Accomack County seaside tidal creeks, and from Parker’s Marsh Natural Area Preserve to Scarsborough Neck (Atlantic Coast Joint Venture 2023). They provide recommended management actions for each area as well as planning tools.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Atlantic Coast Joint Venture (2023). Saltmarsh restoration priorities for the Saltmarsh Sparrow: Virginia. https://acjv.org/documents/VA_SALS_comp_guidance_doc.pdf.

Center for Biological Diversity (2024). Petition seeks Endangered Species Act protection for Saltmarsh Sparrow. Center for Biological Diversity. https://biologicaldiversity.org/w/news/press-releases/petition-seeks-endangered-species-act-protection-for-saltmarsh-sparrow-2024-04-22/.

Chesser, R.T., R. C. Banks, F. K. Barker, C. Cicero, J. L. Dunn, A. W. Kratter, I. J. Lovette, et al. (2009). Fiftieth supplement to the American Ornithologists’ Union check-list of North American birds. The Auk 126:705–714. https://doi.org/10.1525/auk.2009.8709.

Correll, M. D., W. A. Wiest, T. P. Hodgman, W. G. Shriver, C. S. Elphick, B. J. McGill, K. M. O’Brien, and B. J. Olsen (2017). Predictors of specialist avifaunal decline in coastal marshes. Conservation Biology 31:172–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12797.

Greenlaw, Jon S, Chris S. Elphick, William Post, and James D Rising (2020). Saltmarsh Sparrow (Ammospiza caudacuta), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.sstspa.01.

Hines, C. H., L. S. Duval, and B. D. Watts (2024). Saltmarsh Sparrow distribution on Virginia’s Eastern Shore: final report. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-24-08. William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. 30 pp.

Monroe, B. L., Jr., R. C. Banks, J. W. Fitzpatrick, T. R. Howell, N. K. Johnson, H. Ouellet, J. V. Remsen, and R. W. Storer (1995). Fortieth supplement to the American Ornithologists’ Union check-list of North American birds. The Auk 112:819–830.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Watts, B.D. (2004). A recent breeding record of the Saltmarsh Sharp-tailed Sparrow in Gloucester County, Virginia. The Raven 75:128–131.