Introduction

Once known as the Common Moorhen, the Common Gallinule was renamed in 2011 when the North American populations were recognized as a distinct species from what is now known as the Eurasian Moorhen (Gallinula chloropus), which is found in Africa, Europe, and Asia (Bannor and Kiviat 2020). Despite its bright red head shield and yellow-tipped beak, like other secretive marsh birds, the Common Gallinule can be difficult to detect. Common Gallinules have long slender toes, allowing them to walk over floating vegetation. Despite the lack of webbed feet, they are good swimmers and can be found congregating at the edges of open water with dabbling ducks and American Coots (Fulica americana) (Bannor and Kiviat 2020).

The Common Gallinule is considered an uncommon to rare breeder in the Commonwealth, but Virginia falls well within its eastern range (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). Across its broader range, the species is considered widely distributed, although this distribution is patchy and can change from year to year based on ephemeral local conditions (Bannor and Kiviat 2020). Within the Chesapeake Bay region, Common Gallinules can be associated with freshwater and brackish tidal marshes with dense vegetation such as big cordgrass (Spartina cynusoroides) and cattails (Typha spp.) (Wilson and Watts 2007). They can also be found breeding in nontidal marshes, as well as around lakes and ponds, within their eastern range (Bannor and Kiviat 2020).

Breeding Distribution

Given the Common Gallinule is an uncommon to rare breeder in the state, its distribution could not be modeled. For more information on where this species occurs in Virginia, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

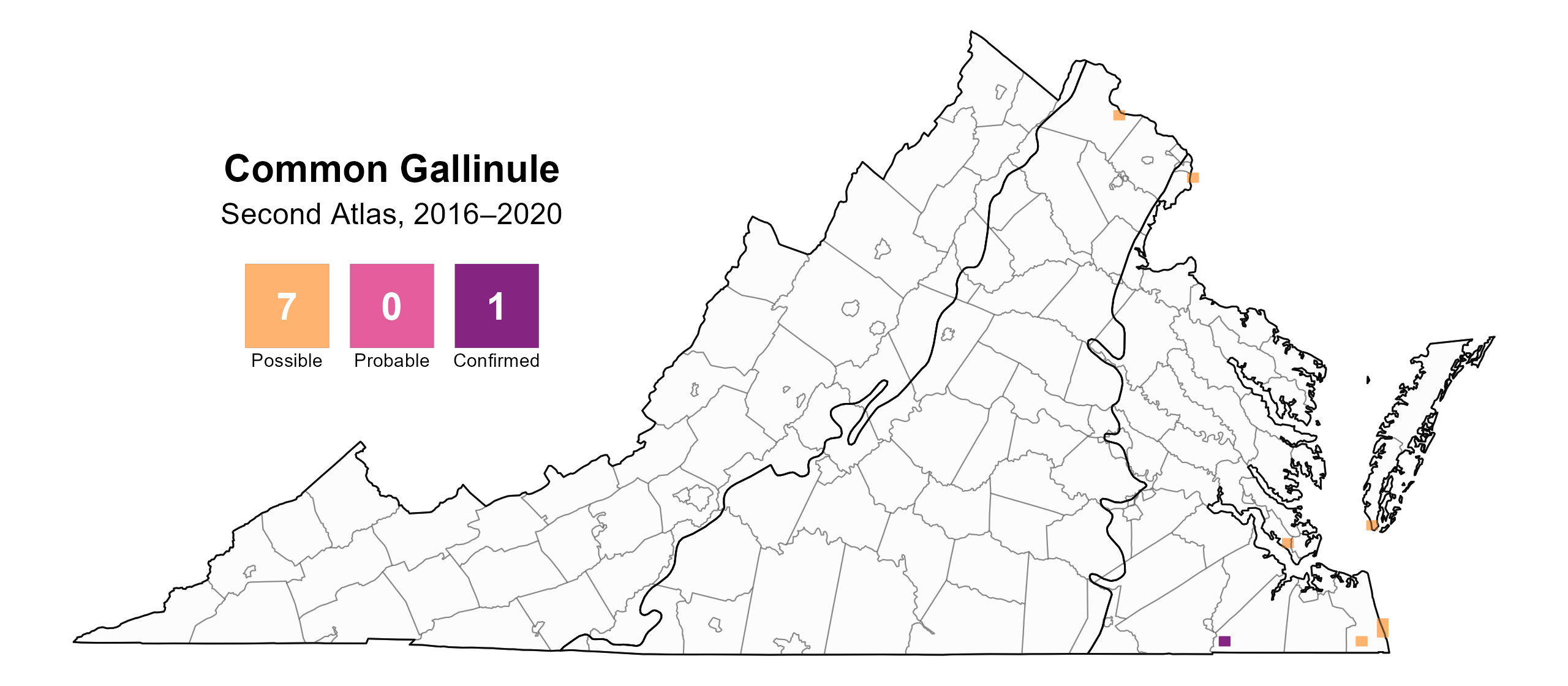

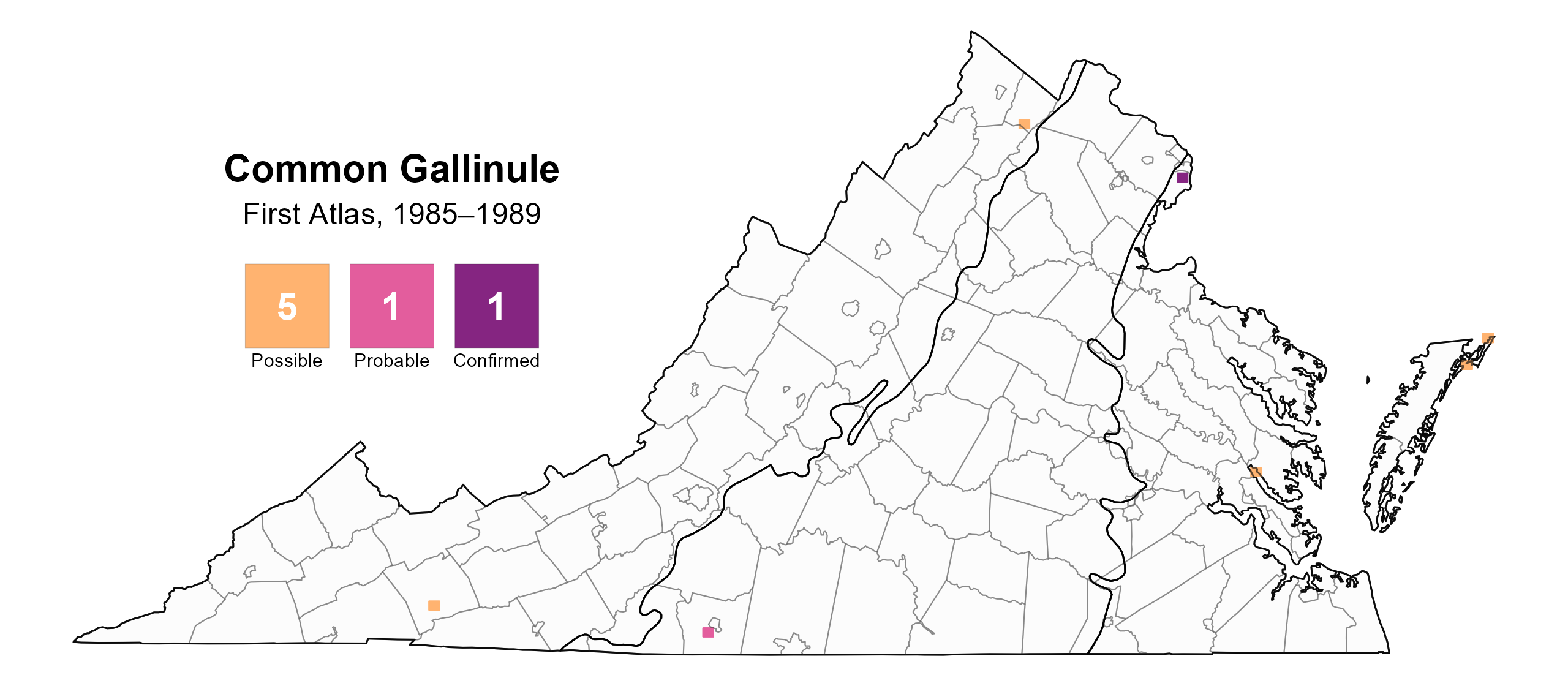

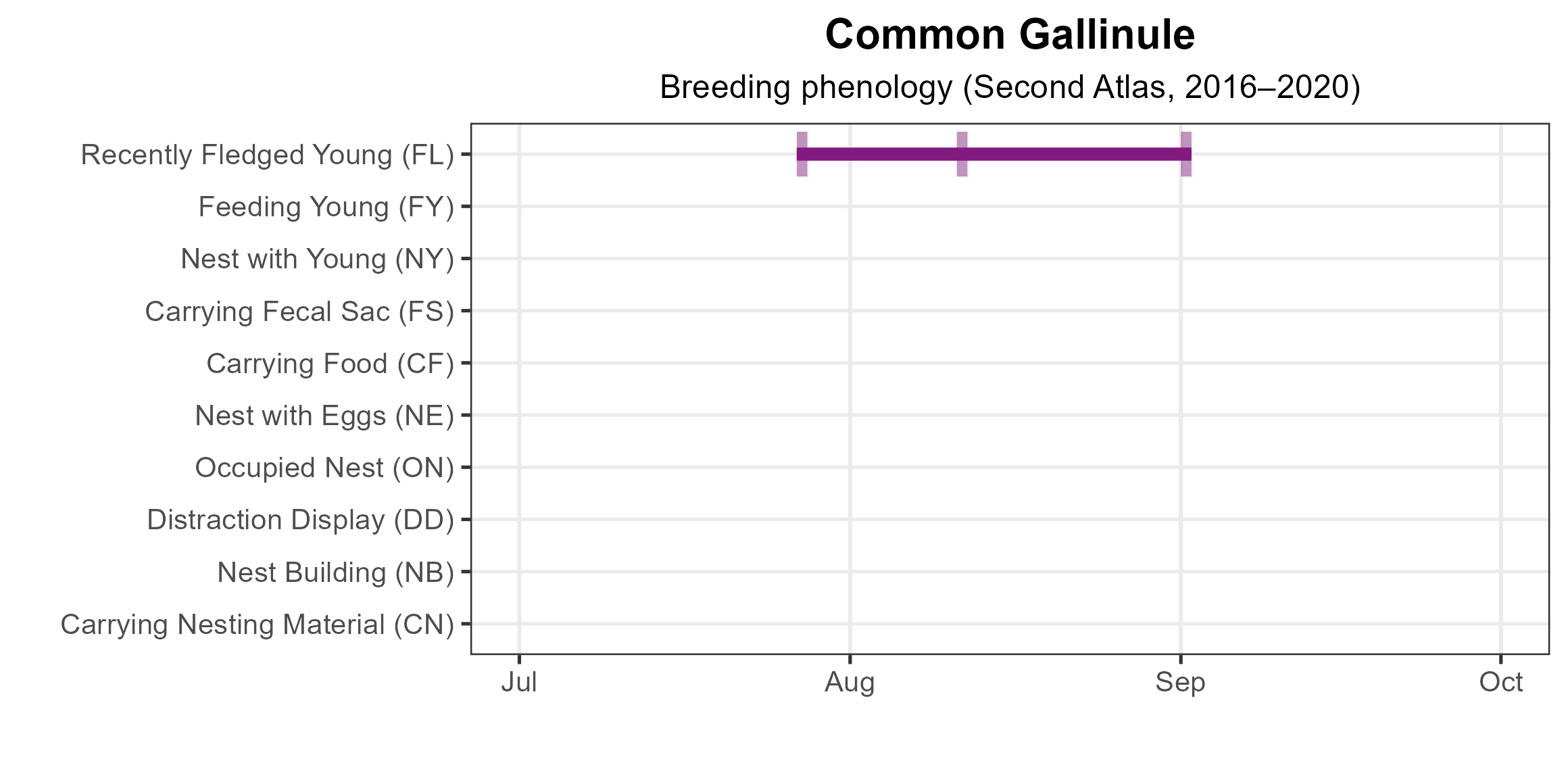

Common Gallinules were very sporadically observed breeding in the Coastal Plain and Piedmont regions (Figure 1). The only breeding confirmations were of recently fledged young reported on July 27, August 11, and September 1, 2019, from the same location at a pond in Suffolk County (Figures 1 and 3). Similarly, the species was confirmed as a breeder in only one block during the First Atlas (Figure 2).

Nine records of possible breeders (individuals observed in appropriate breeding habitat) in the Second Atlas were distributed at the following locations in the Coastal Plain and northern Piedmont: Bles Park, Loudon County; Dyke Marsh Wildlife Preserve, Fairfax County; Magothy Bay Natural Area Preserve, Northampton County; Sandy Bottom Nature Park, Hampton County; Princess Anne Wildlife Management Area and Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Virginia Beach (Figure 1).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Common Gallinule breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Common Gallinule breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Common Gallinule phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Abundance could not be modeled for Common Gallinule as the species was not detected during point count surveys. Similarly, this species is not readily detected by the North American Breeding Bird Survey, which relies on roadside counts that tend not to capture its preferred habitat, so no estimates of credible population trends are available at any geographic scales.

Conservation

Because relatively few records of Common Gallinule exist for Virginia, especially during the breeding season, little is known about its nesting ecology and habitat associations in the Commonwealth. There is no evidence for an expansion or contraction of its population between Atlases. Its status as a rare breeder in the Commonwealth, where it can also be seen during the fall and winter months, will likely continue. Although it is not a prominent component of Virginia’s avifauna, its association with marshes (though not exclusive) means that it will benefit from conservation actions taken to protect, manage, and restore marshlands for the broader marsh bird community.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Bannor, B. K. and E. Kiviat (2020). Common Gallinule (Gallinula galeata), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.comgal1.01.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s Birdlife: An Annotated Checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Wilson, M.D., B.D. Watts, and D.F. Brinker (2007). Status review of Chesapeake Bay marsh lands and breeding marsh birds. Waterbirds 30: 122–137. https://doi.org/10.1675/1524-4695(2007).