Introduction

The Chipping Sparrow is an abundant migrant that breeds throughout the Commonwealth, arriving in mid-March and departing in early November, and it is a regular but uncommon winter species in the Coastal Plain and southern Piedmont regions (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). Nicknamed “chippie”, this species is familiar to birders and nonbirders alike due to its affinity for human-modified environments, including wood edges, campuses, neighborhoods, young clear cuts, orchards, and Christmas tree plantations (Clark 1937; Ruckel 1975).

Breeding Distribution

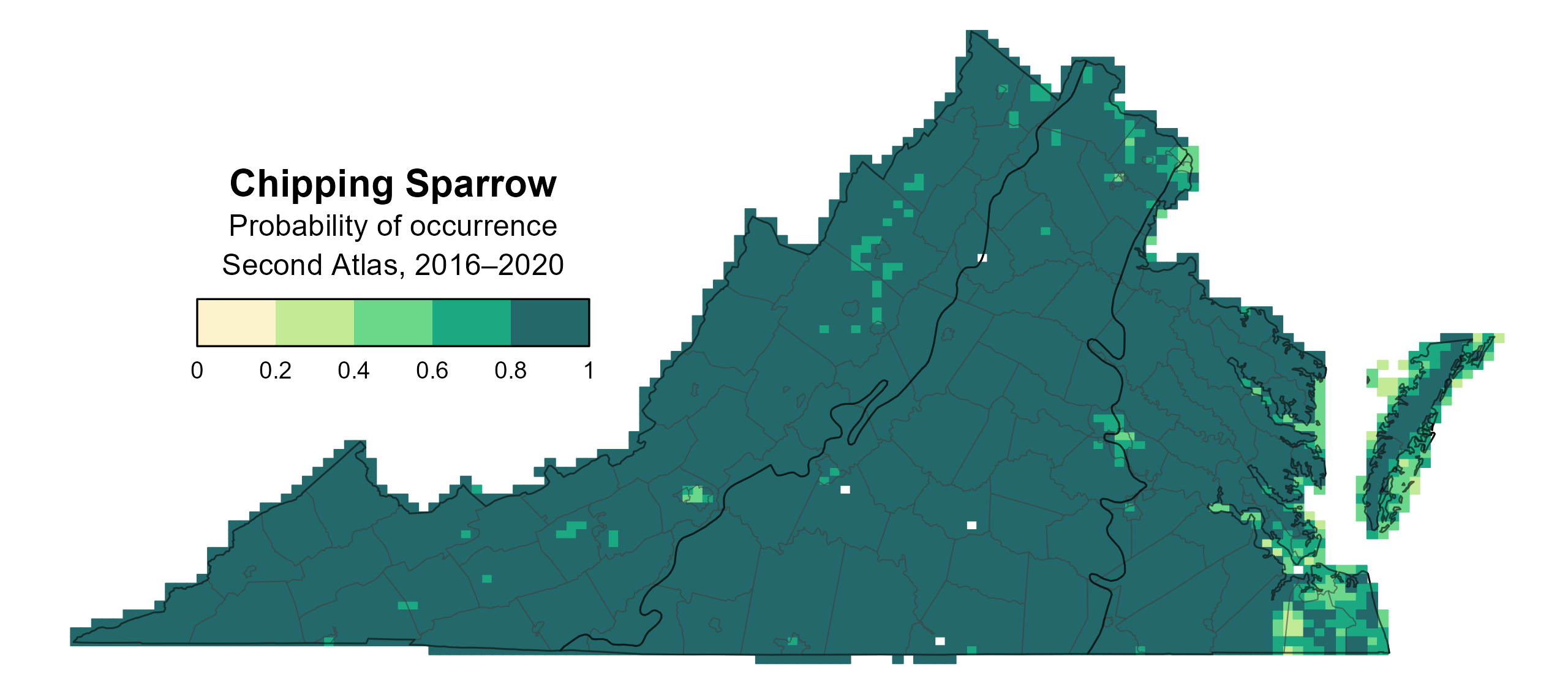

Chipping Sparrows are found in every region of the state (Figure 1). The species is slightly less likely to occur in highly urbanized areas in Northern Virginia, Richmond, and Roanoke and in the extensive forests of the Great Dismal Swamp. However, they can occur anywhere given a suitable patch of habitat. The likelihood of Chipping Sparrows occurring in a block increases as the proportion of forest cover and the number of habitat types increase, indicative of its preference for woodlands, forest edges, and disturbed areas (Middleton 2020).

Chipping Sparrow’s distribution during the First Atlas and its change between the two Atlas periods could not be modeled due to model limitations (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on the species’ occurrence during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Chipping Sparrow breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Breeding Evidence

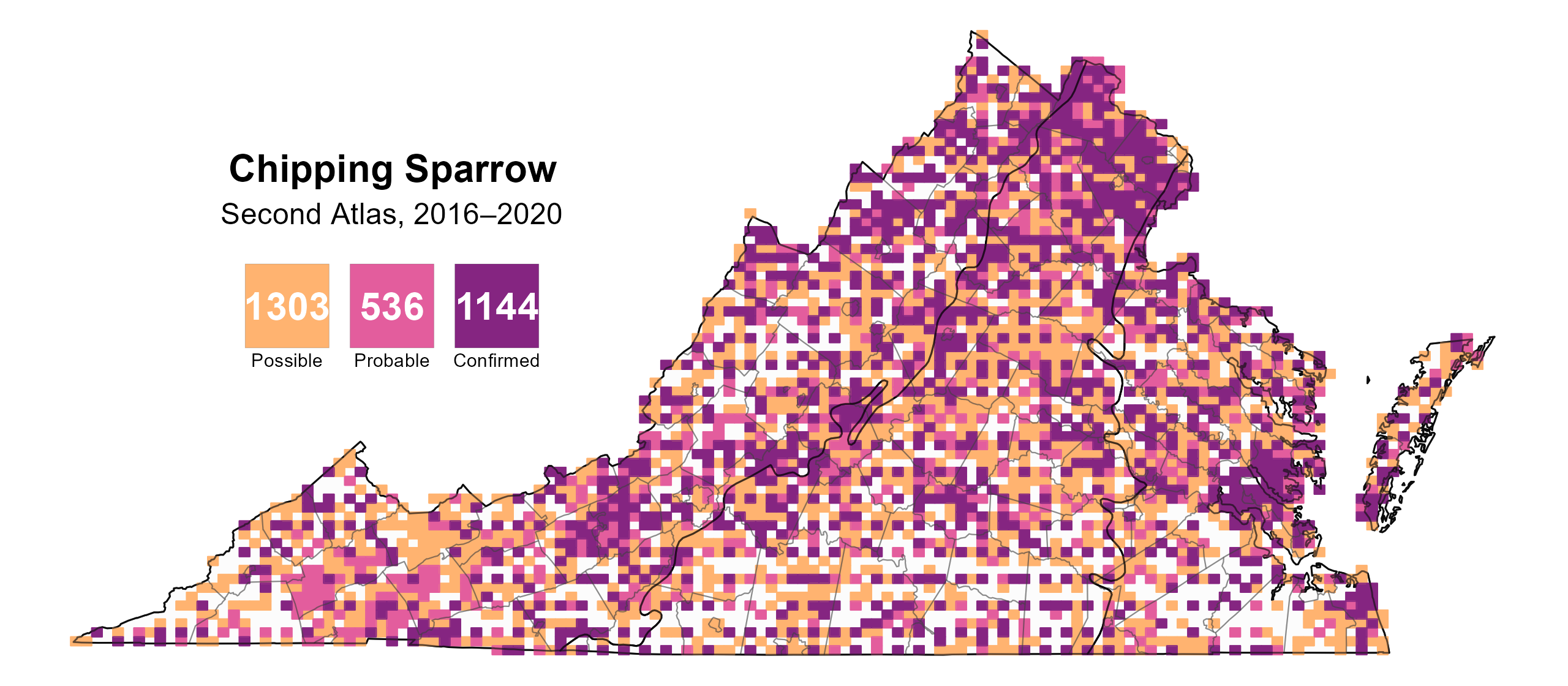

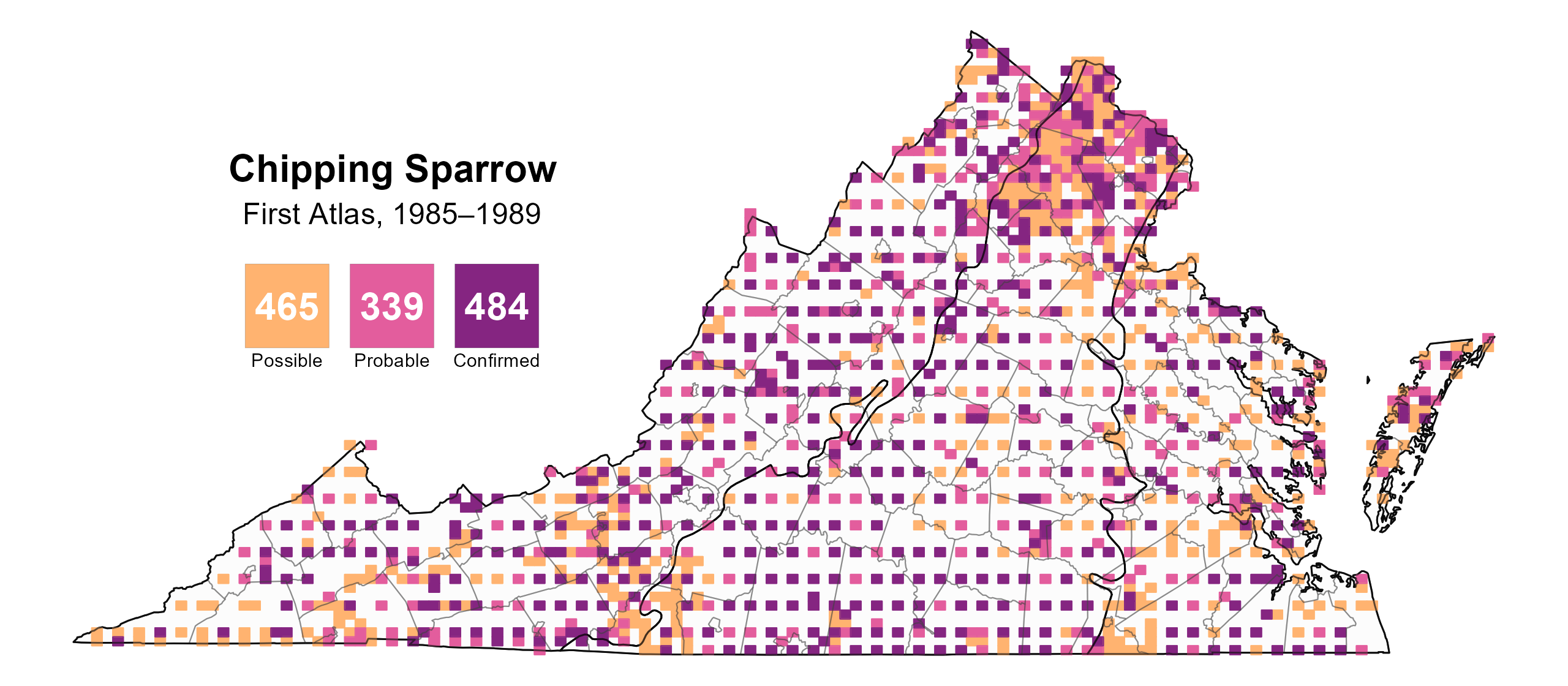

Chipping Sparrows were confirmed breeders in 1,144 blocks and 114 counties and probable breeders in an additional five counties (Figure 2). Breeding observations were recorded in all regions of the state during the First Atlas as well (Figure 3).

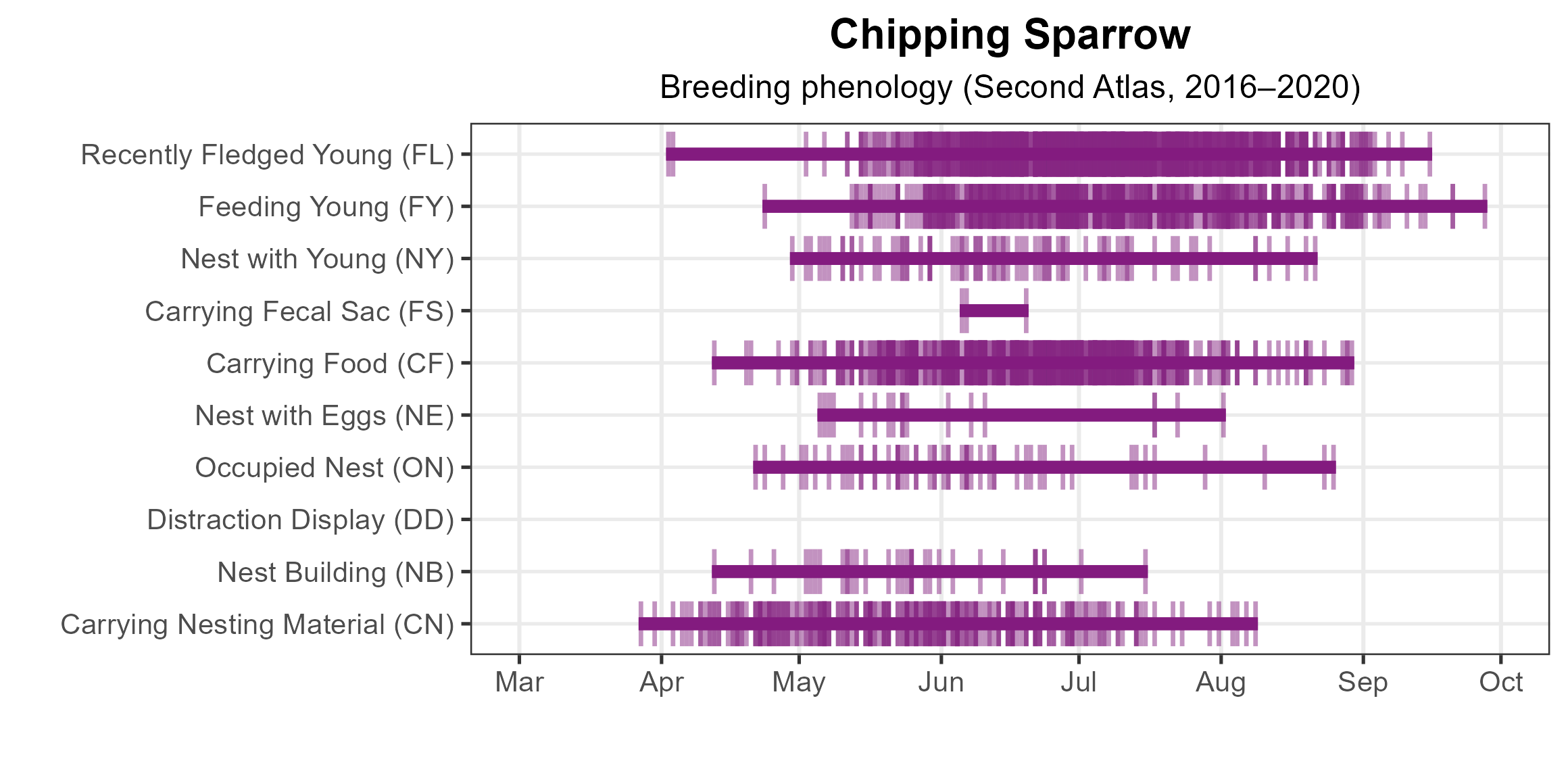

Observers documented breeding as early as March 27 (carrying nesting material), with birds seen carrying food from April 12 (Figure 4). Breeding continued to be documented through September 27 (feeding young). Additionally, observers documented Chipping Sparrows performing every type of breeding activity; as a common bird of edges and suburban areas, the species is relatively easy to observe.

For more general information on the breeding habits of the Chipping Sparrow, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Chipping Sparrow breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Chipping Sparrow breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Chipping Sparrow phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

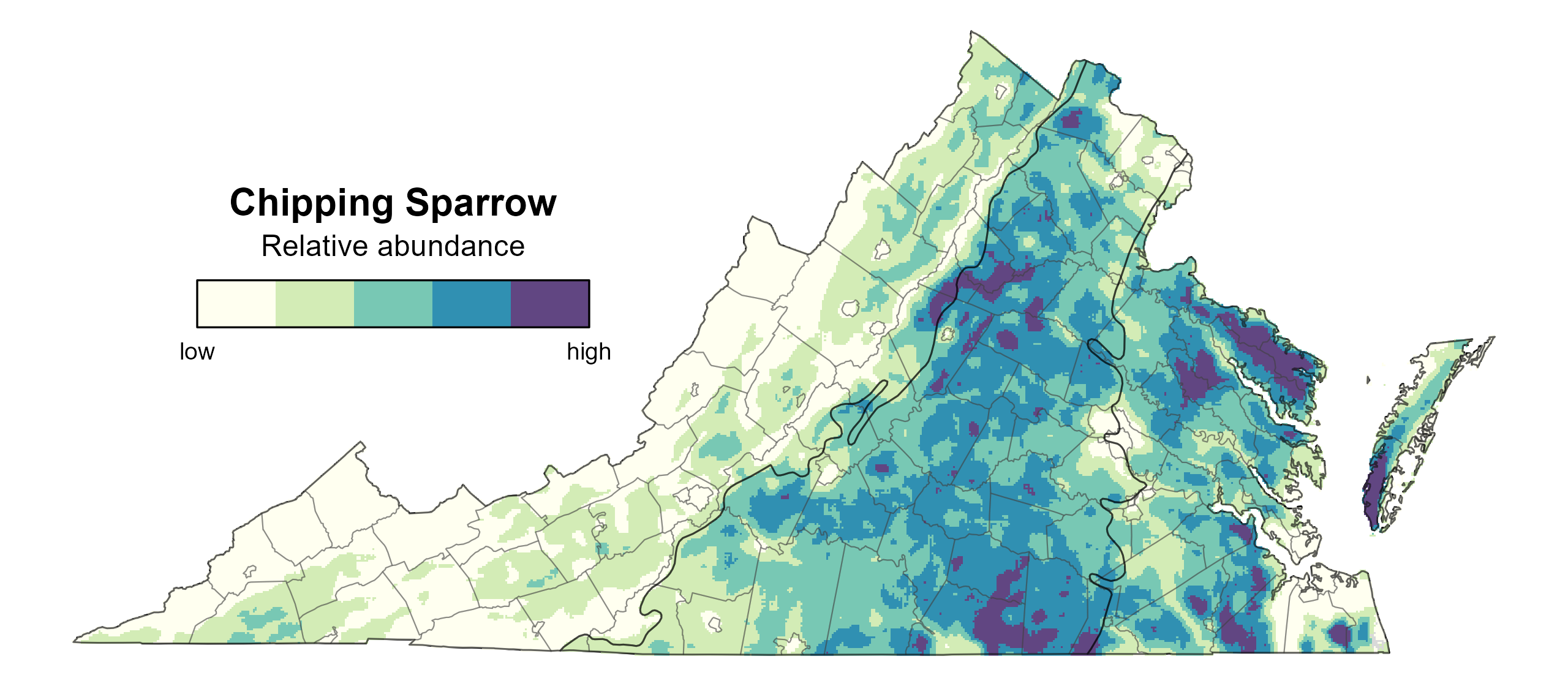

Chipping Sparrow relative abundance was estimated to be moderate to high in the Coastal Plain and Piedmont regions and lower in the Mountains and Valleys region at higher elevation forests along the Blue Ridge, Allegheny, and Cumberland Mountains and around major cities in all regions (Figure 5).

The total estimated Chipping Sparrow population in the state is approximately 1,969,000 individuals (with a range between 1,598,000 and 2,429,000). This makes the species the fourth most abundant breeder in the state (of those for which an abundance model was developed) and the most common short-distance migrant.

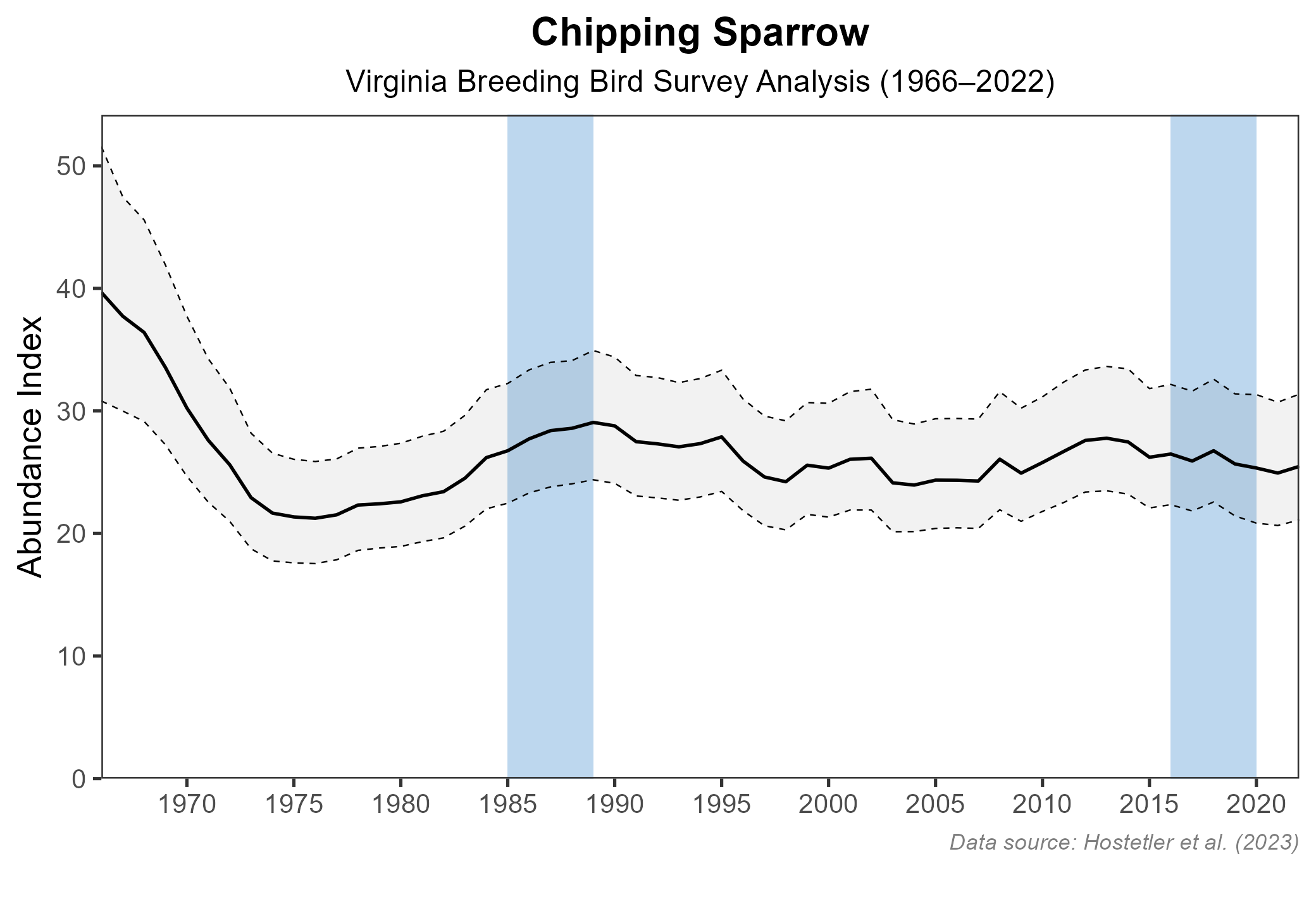

Although the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) reported a significant decrease of 0.79% per year from 1966–2022, with the steepest declines in the earliest period of the BBS (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 6), between the First and Second Atlases, BBS data showed a nonsignificant decrease of 0.18% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 5: Chipping Sparrow relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 6: Chipping Sparrow population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Because Chipping Sparrows are extremely abundant, this species is not the focus of any specific conservation efforts in Virginia.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Clark, M. (1937). Sweet Briar nesting notes. The Raven 8:51–54.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Middleton, A. L. (2020). Chipping Sparrow (Spizella passerina), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.chispa.01.

Penhollow, M. E., and F. Stauffer (2000). Large-scale habitat relationships of neotropical migratory birds in Virginia. The Journal of Wildlife Management 64:362–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/3803234.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Ruckel, S. W. (1975). Relative abundance of birds in cut and uncut forests in southwestern Virginia. The Raven 46:59–64.