Introduction

The American Herring Gull is a typical human-commensal gull alongside its smaller cousin, the Ring-billed Gull (Larus delawarensis). Unlike the Ring-billed Gull, the American Herring Gull is present year-round in Virginia. These birds are adaptable, clever foragers, choosing to drop clams from great heights onto rocks or pavement to break them open (Weseloh et al. 2024). In Virginia, it has been found that adults and juveniles are equally skilled at this behavior, though juveniles take longer to assess which clams are worth dropping (Cristol et al. 2017).

American Herring Gulls are a relatively recent addition to Virginia’s breeding avifauna. In Bailey’s Birds of Virginia (Bailey 1913), the species was only briefly mentioned as present in winter. The first documented breeding in Virginia was on Cobb Island in 1948 (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). In the following decades, it became more common, to the point where it is sometimes considered a nuisance species by wildlife managers as it predates on other smaller seabirds and shorebirds. Today, it is an abundant permanent resident along the coast and tidal rivers and is locally common inland during migration and uncommon during winter (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007).

Breeding Distribution

The American Herring Gull was well-covered during the Second Atlas by the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey, a coastal census conducted by the Center for Conservation Biology in collaboration with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) and The Nature Conservancy. The survey identifies nesting locations of this and other species that breed in colonies. Because the American Herring Gull only breeds within the survey area, there was no need to model its distribution. For information on where the species occurs in Virginia’s Coastal Plain, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

Given the breeding biology of the species, the American Herring Gull is unlikely to have nested in blocks without confirmed breeding evidence (see Interpreting Species Accounts). Confirmation of breeding was based on records generated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey in 2018. Additional breeding confirmations were reported by Atlas volunteers in other years of the Second Atlas period.

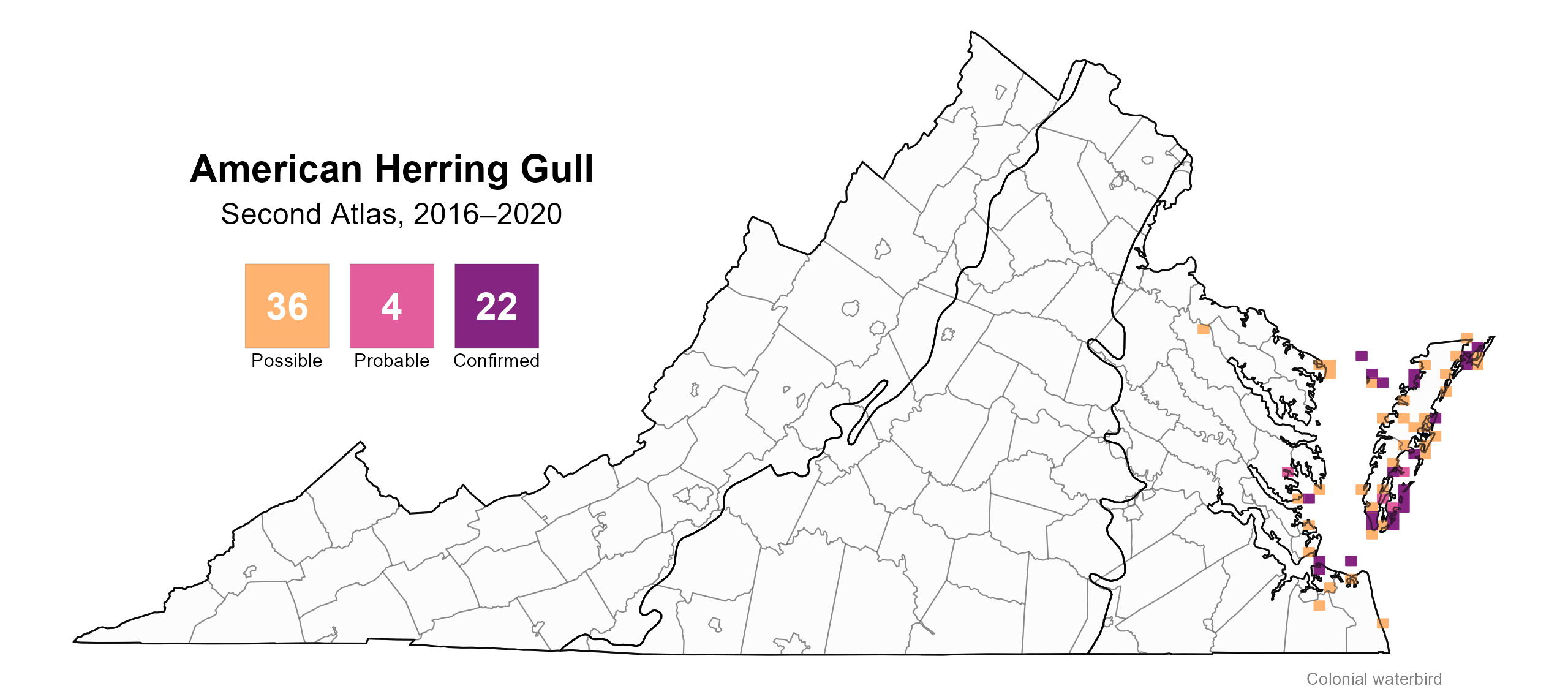

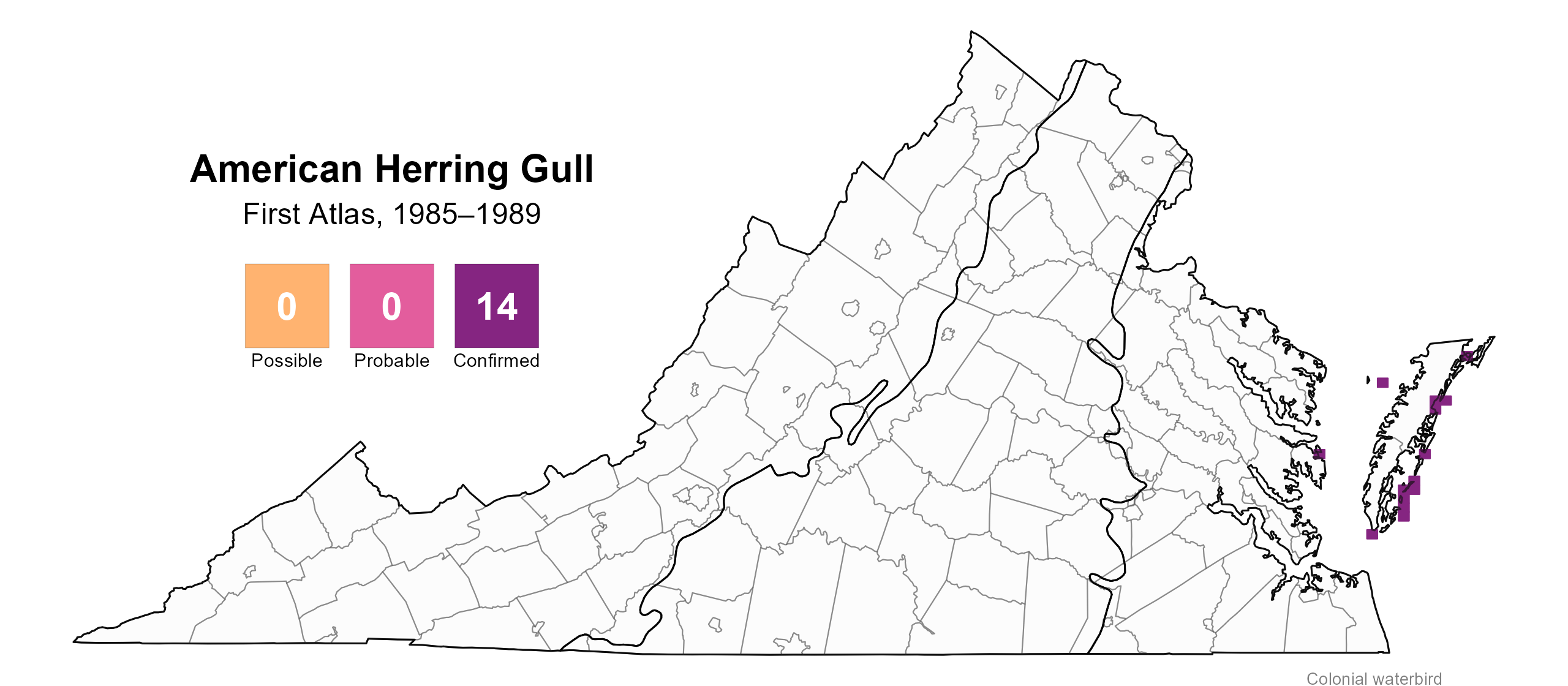

American Herring Gulls were confirmed on Atlantic and Chesapeake Bay marshes, as well as at sites on the Western Shore of the Chesapeake Bay (Figure 1). Breeding was confirmed in 22 blocks in four counties (Accomack, Gloucester, Mathews, and Northampton) and in three cities (Hampton, Norfolk, and Virginia Beach). The distribution of breeding sites was largely similar to that in the First Atlas, but breeding sites further expanded in the Hampton Roads area region during the Second Atlas, where it did not nest during the First Atlas (Figure 2). They nested on manmade structures including the first island of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (HRBT), and the concrete ships off Kiptopeke State Park, in addition to marshes and small islands.

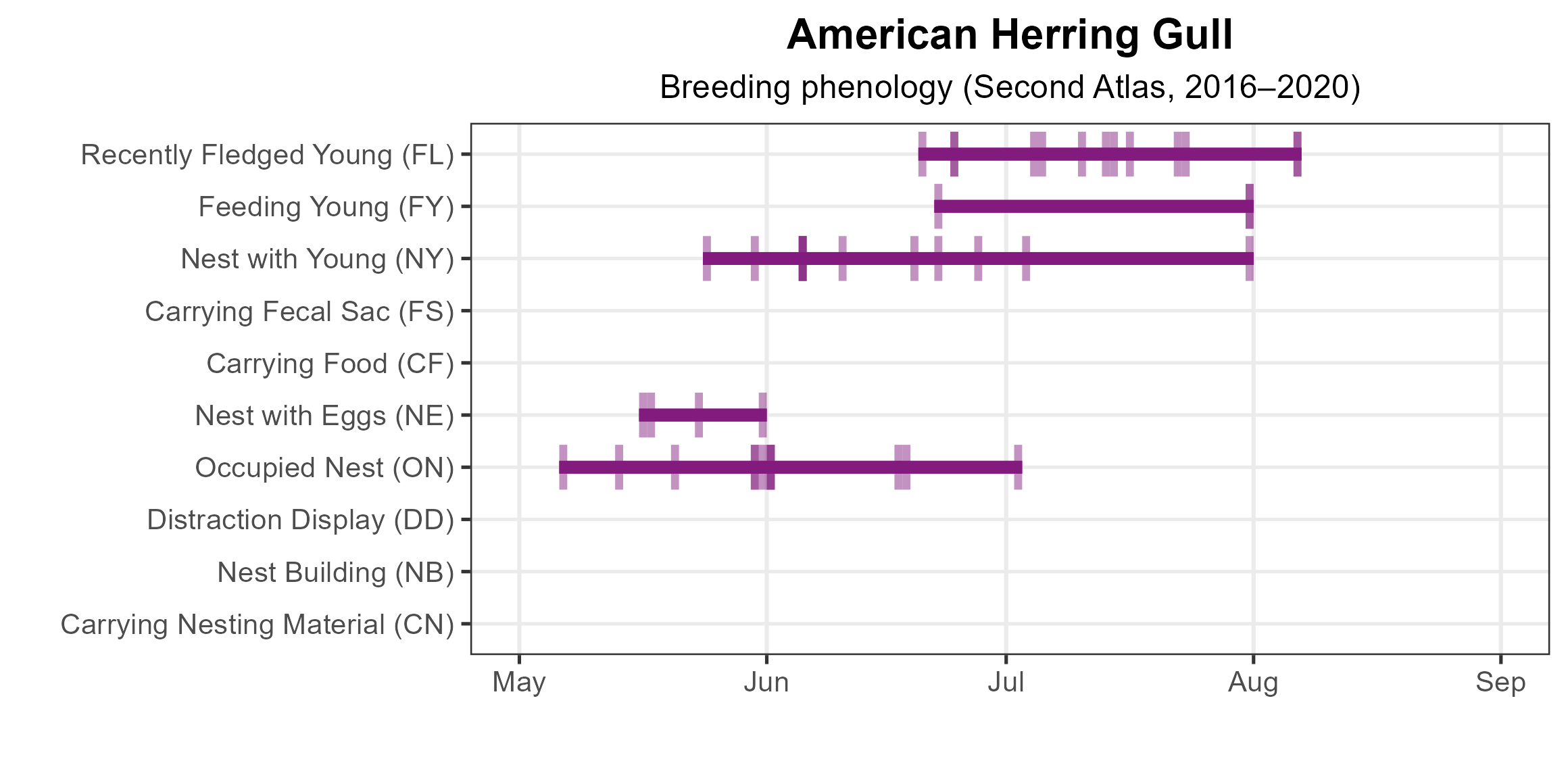

American Herring Gulls were observed on nests from May 6 (Figure 3). Nests had eggs from May 16 to May 31 and young from May 24 to July 31. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Herring Gull, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: American Herring Gull breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category. Nesting is unlikely outside of confirmed blocks.

Figure 2: American Herring Gull breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: American Herring Gull phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

The American Herring Gull had too few detections during the Atlas point count surveys to develop an abundance model. However, the distribution and size of American Herring Gull colonies derived from the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey are displayed on the CCB Mapping Portal.

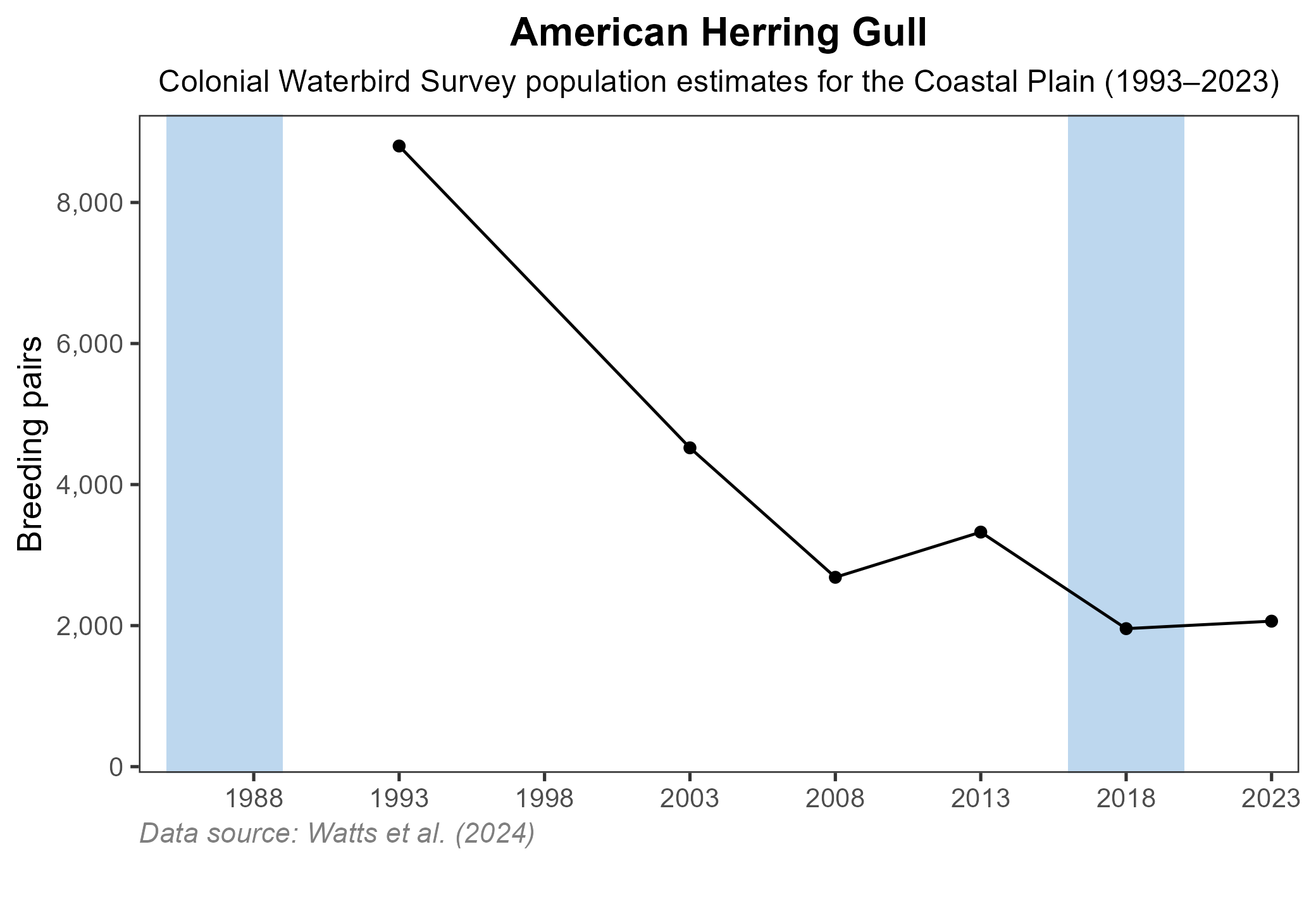

At the time of the First Atlas, annual counts of breeding Herring Gulls were stable to increasing (Williams et al. 1993). However, based on the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey, a sharp decline was recorded beginning in the 2000s for many marsh-nesting birds, including the American Herring Gull. From 8,801 pairs in 1993, the species dropped precipitously, bottoming out at 1,957 pairs in 2018 (Watts et al. 2019, 2024; Figure 4). Declines have been most prominent in Northampton County, with Chincoteague in Accomack County serving as the population stronghold with nearly 50% of the pairs (Watts et al. 2024).

Figure 4: American Herring Gull population trend for Virginia’s Coastal Plain. This chart illustrates the number of breeding pairs as estimated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey (Watts et al. 2024). A data point is not included for 1998, as the Survey covered a smaller geographic area in that year. The vertical light blue bars represent the periods corresponding to the First Atlas (1985–1989) and Second Atlas (2016–2020).

Conservation

The American Herring Gull is classified a Tier II (Very High Conservation Need) Species of Greatest Conservation Need in Virginia’s 2025 Wildlife Action Plan (VDWR 2025). Like other marsh-nesting species, it is vulnerable to the loss of breeding sites to sea-level rise and marsh subsidence. American Herring Gulls have sometimes been implicated in the decline of other barrier island nesting species in Virginia (O’Connell and Beck 2003) because they are consummate opportunists who will depredate eggs and chicks of other species. One seabird colony containing American Herring Gulls was recently displaced when the Virginia Department of Transportation began a project to expand the HRBT. In 2020, the South Island HRBT expansion project paved over the former nesting site. The VDWR and partners were able to provide alternative habitat on the historic Fort Wool (also known as Rip Raps Island) and floating barges, which now provide replacement habitat for multiple nesting seabird species, including the American Herring Gull (Sweeney et al. 2024).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Bailey, H. H. (1913). The birds of Virginia. J.P. Bell Company, Incorporated, Lynchburg, VA, USA.

Cristol, D. A., J. G. Akst, M. K. Curatola, E. G. Dunlavey, K. A. Fisk, and K. E. Moody (2017). Age-related differences in foraging ability among clam-dropping Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus). The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 129:301–310.

O’Connell, T. J., and R. A. Beck (2003). Gull predation limits nesting success of terns and skimmers on the Virginia barrier islands. Journal of Field Ornithology 74:66–73.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Sweeney, C., K. Hunt, J. Fraser, and S. Karpanty (2024). Assessing avian response to the relocation of Virginia’s largest seabird colony, 2024 annual report. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. B., and A. L. Wilke (2019). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2018 breeding season. CCBTR-19-06. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. B., and A. L. Wilke (2024). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2023 breeding season. CCBTR-24-12. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Weseloh, D. V., C. E. Hebert, M. L. Mallory, A. F. Poole, J. C. Ellis, P. Pyle, and M. A. Patten (2024). American Herring Gull (Larus smithsonianus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (B. K. Keeney and S. M. Billerman, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.amhgul1.01.

Williams, B., B. Akers, R. A. Beck, and J. Via (1993). The 1992 colonial and beach-nesting waterbird survey of the Virginia barrier islands. The Raven 64:24–29.