Introduction

A species of rail, the American Coot is in the same family as its more secretive, marsh-dependent cousins, such as King Rail (Rallus elegans), Clapper Rail (R. crepitans), and Virginia Rail (R. limicola). Its more conspicuous appearance, dark body with a bright white bill and forehead, and its habit of congregating on open water with large rafts of ducks in the winter months distinguish it from other rail species. Common to locally common in the winter in Virginia (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007), the species also has a very small, scattered breeding population in the Commonwealth, which is associated with freshwater wetlands.

Breeding Distribution

Like many other eastern states, Virginia falls outside of the American Coot’s core breeding range, which lies further west (Brisbin and Mowbay 2020). The species is considered a casual breeder within Virginia, with records scattered in both geographic space and time (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). Too few breeding observations were reported during the Second Atlas to develop a distribution map for the American Coot. For more information on its distribution, see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

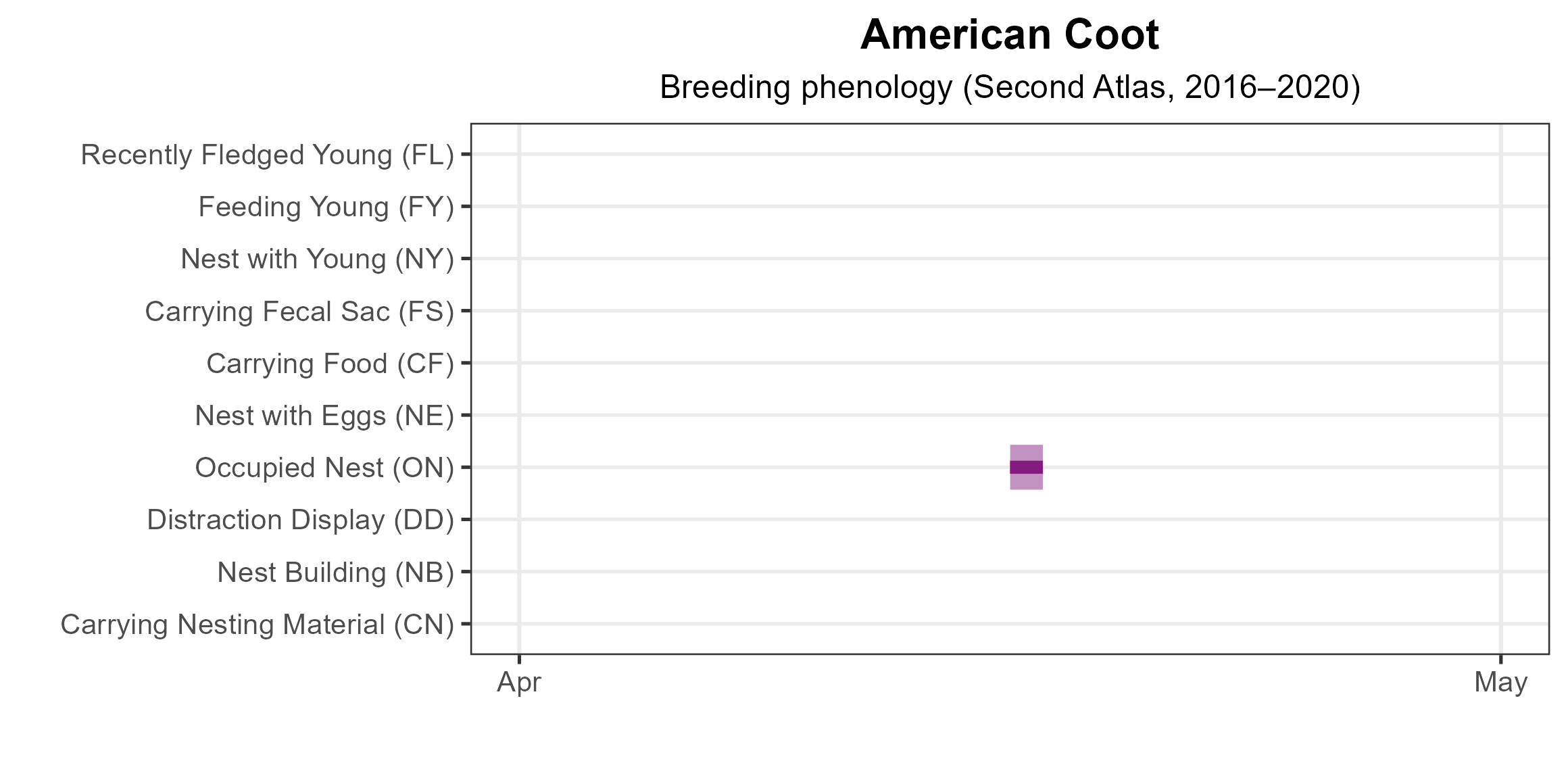

American Coots were reported from only four sites. On April 16, 2017, an Atlas volunteer observed a pair at a nest at the Dutch Gap Conservation Area/Henricus Historical Park in Chesterfield County (Figure 1). This was the only reported breeding confirmation. Probable breeding was documented through a courtship display involving a pair preening one another on May 22 near the Roanoke Sewage Treatment Plant within the city of Roanoke; one individual was noted as being on what was thought to be a nest, but it could have been a display platform (Brisbin and Mowbay 2020).

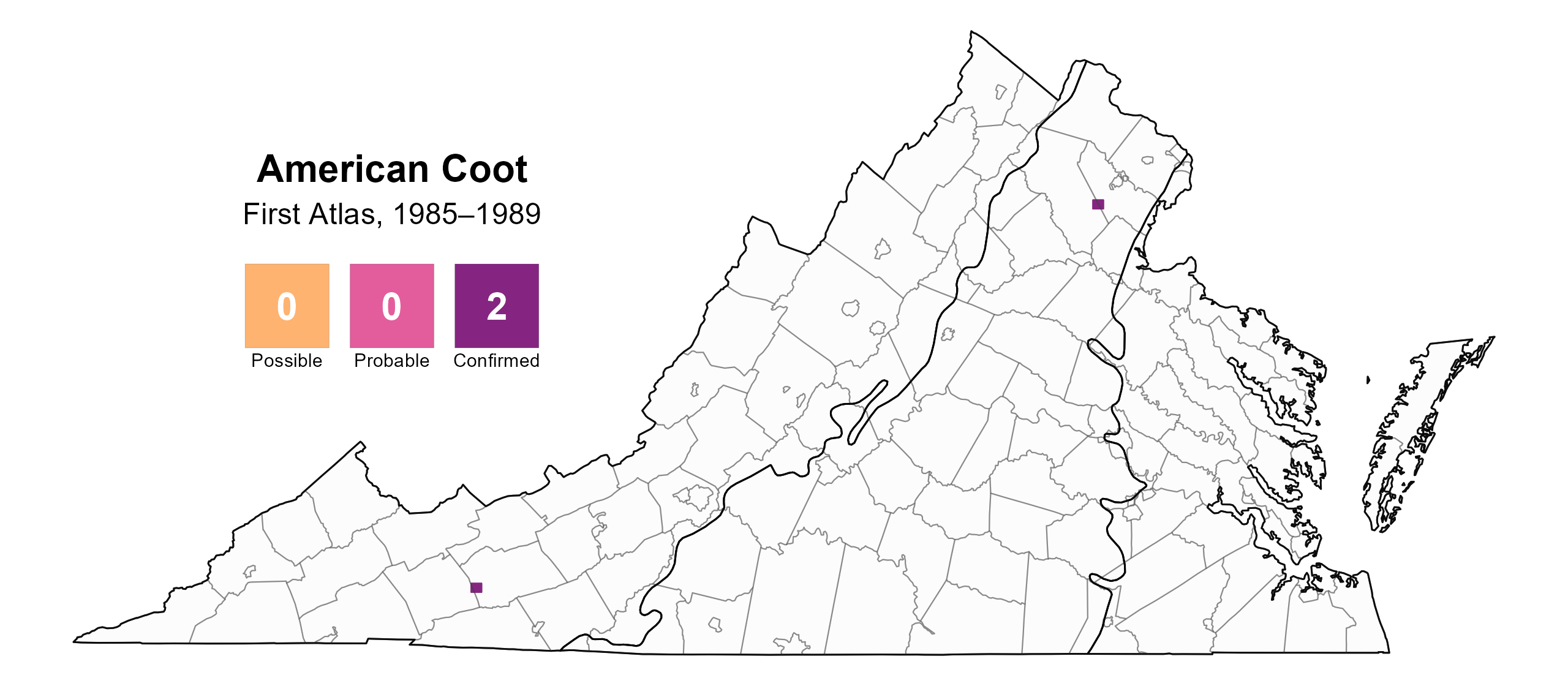

American Coots were observed during the breeding season and in appropriate habitat within the Beasley Tract of the Princess Anne Wildlife Management Area in Virginia Beach and at Pohick Bay Regional Park in Fairfax County. The species was only reported from two blocks during the First Atlas, in both cases as a confirmed breeder (Figure 2).

Figure 1: American Coot breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: American Coot breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: American Coot phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

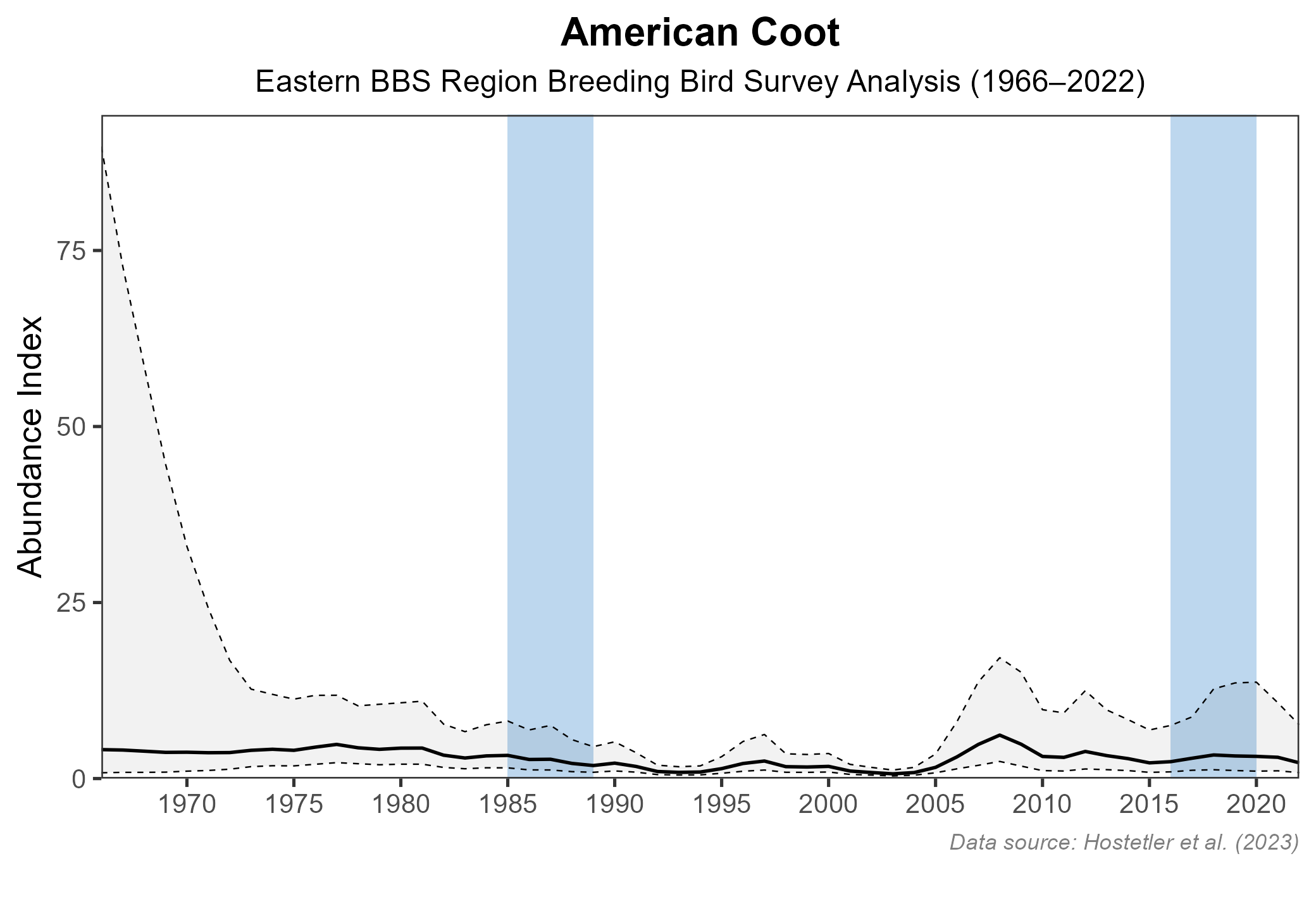

American Coots were not detected in sufficient numbers during Atlas point counts to allow for development of an abundance model. Credible population trends for the species could only be estimated at larger geographic scales by the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS). The 1966–2022 trend for the Eastern BBS region, which includes much of Canada, showed a nonsignificant annual decline of 1.11% (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 3).

Figure 3: American Coot population trend for the Eastern region as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Like other aquatic bird species with marginal breeding populations in Virginia, such as the Pied-billed Grebe (Podilymbus Podiceps) and Common Gallinule (Gallinula galeata), relatively little is known about the breeding habits and habitats of the American Coot in the Commonwealth. This species is part of a broader breeding marsh bird community that will benefit from freshwater wetland conservation. However, given the greater importance of the Commonwealth to the species during the nonbreeding season, the most important conservation strategy in Virginia may be to maintain high-quality migratory stopover and wintering habitat.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Brisbin Jr., I. L. and T. B. Mowbray (2020). American Coot (Fulica americana), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.y00475.01.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966 – 2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Rottenborn, S.C., and E.S. Brinkley (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.