Introduction

All warblers eat “worms” (hairless caterpillars), but the Worm-eating Warbler has the distinction of being triply named for it. In addition to its English common name, its genus derives from the Greek for worm (helmins) hunter (theros) and its specific name from Latin for worm- (vermis) eating (vorus). This caramel-colored, ground-nesting warbler is primarily a resident of oak (Quercus spp.)-hickory (Carya spp.) forests on steep slopes (Ruhl et al. 2018).

Its insect-like song and understated plumage may not capture the same interest as some of its gaudier warbler cousins. However, a careful observer will appreciate its dashing buffy and black-striped head and delight in its foraging specialty: dangling upside-down to hunt prey in hanging dead leaves. Worm-eating Warblers are uncommon to rare breeders and migrants in the Coastal Plain and eastern Piedmont, becoming more common in the western Piedmont and in the Mountains and Valleys (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). This species is considered a forest interior specialist as well as area-sensitive (Vitz et al. 2020), uncommon in small forest patches within fragmented forest landscapes.

Breeding Distribution

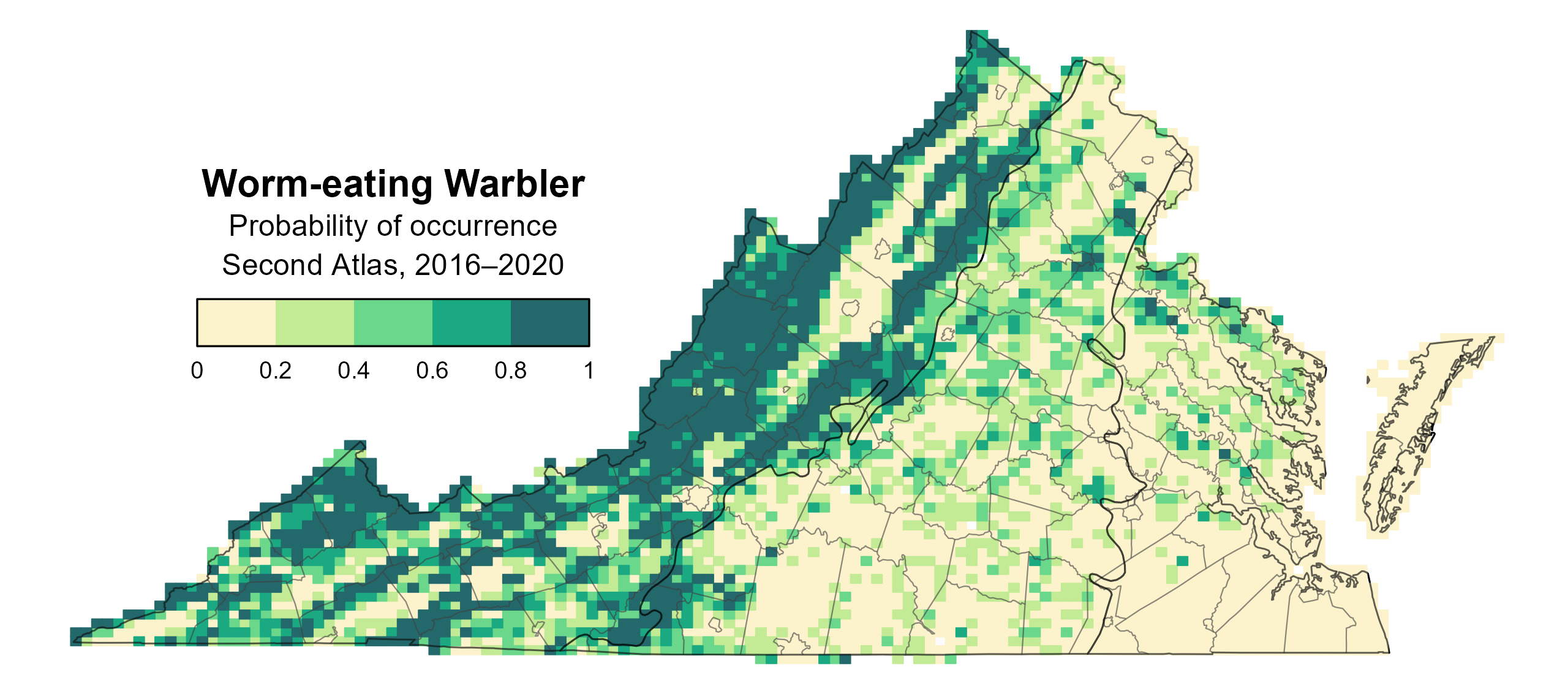

Worm-eating Warblers occur in all regions of the state, but they are most commonly found in the forested Mountains and Valleys region. However, they can also be found in large forest patches throughout the Piedmont and Coastal Plain (Figure 1). Their likelihood of occurrence increases as the amount of forest cover and forest patch size increase in a block. They are less likely to occur where markers of forest fragmentation, such as early successional and forest edge habitats, are present.

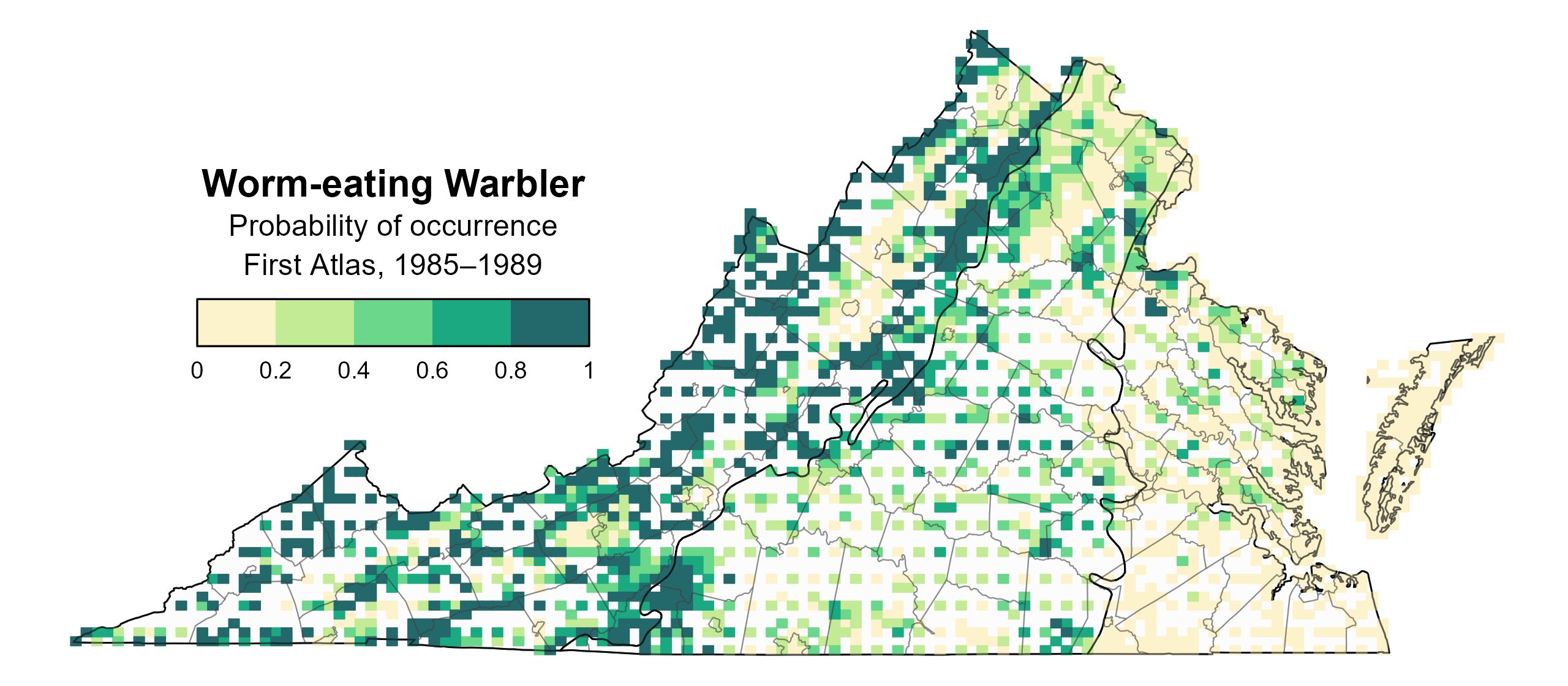

Between the First and Second Atlases (Figures 1 and 2), the Worm-eating Warbler’s likelihood of occurrence decreased slightly in some small areas in the more central part of the Piedmont region. Throughout most of the state, however, its probable occurrence remained the same (Figure 3).

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Worm-eating Warbler breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Worm-eating Warbler breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Worm-eating Warbler change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

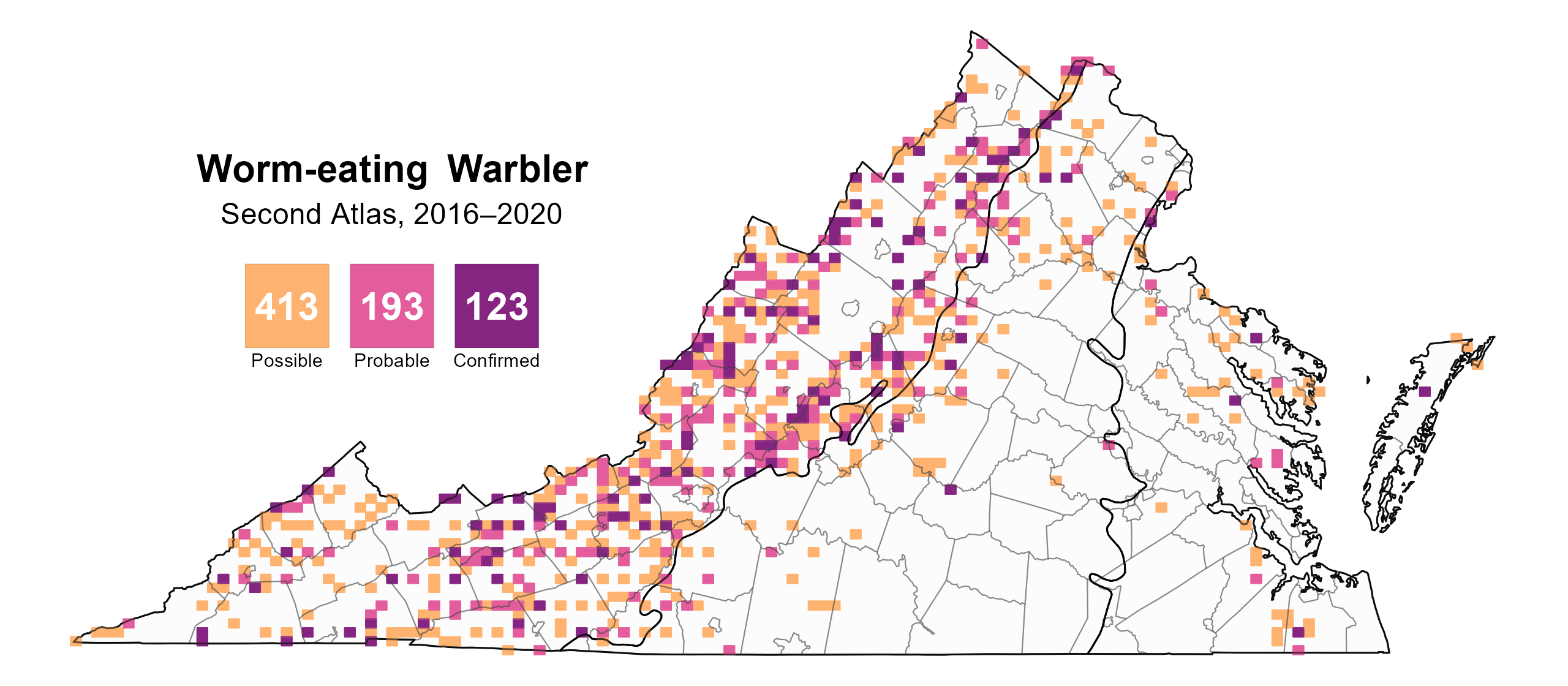

Worm-eating Warblers were confirmed breeders in 123 blocks across 42 counties and probable breeders in an additional 20 counties (Figure 4). The distribution of breeding observations during the Second Atlas was largely similar to that during the First Atlas (Figure 5), with new confirmations in some areas, such as on the Middle Peninsula and Eastern Shore. Some counties, such as Fairfax, had sightings and possible breeders during both Atlases but no confirmations.

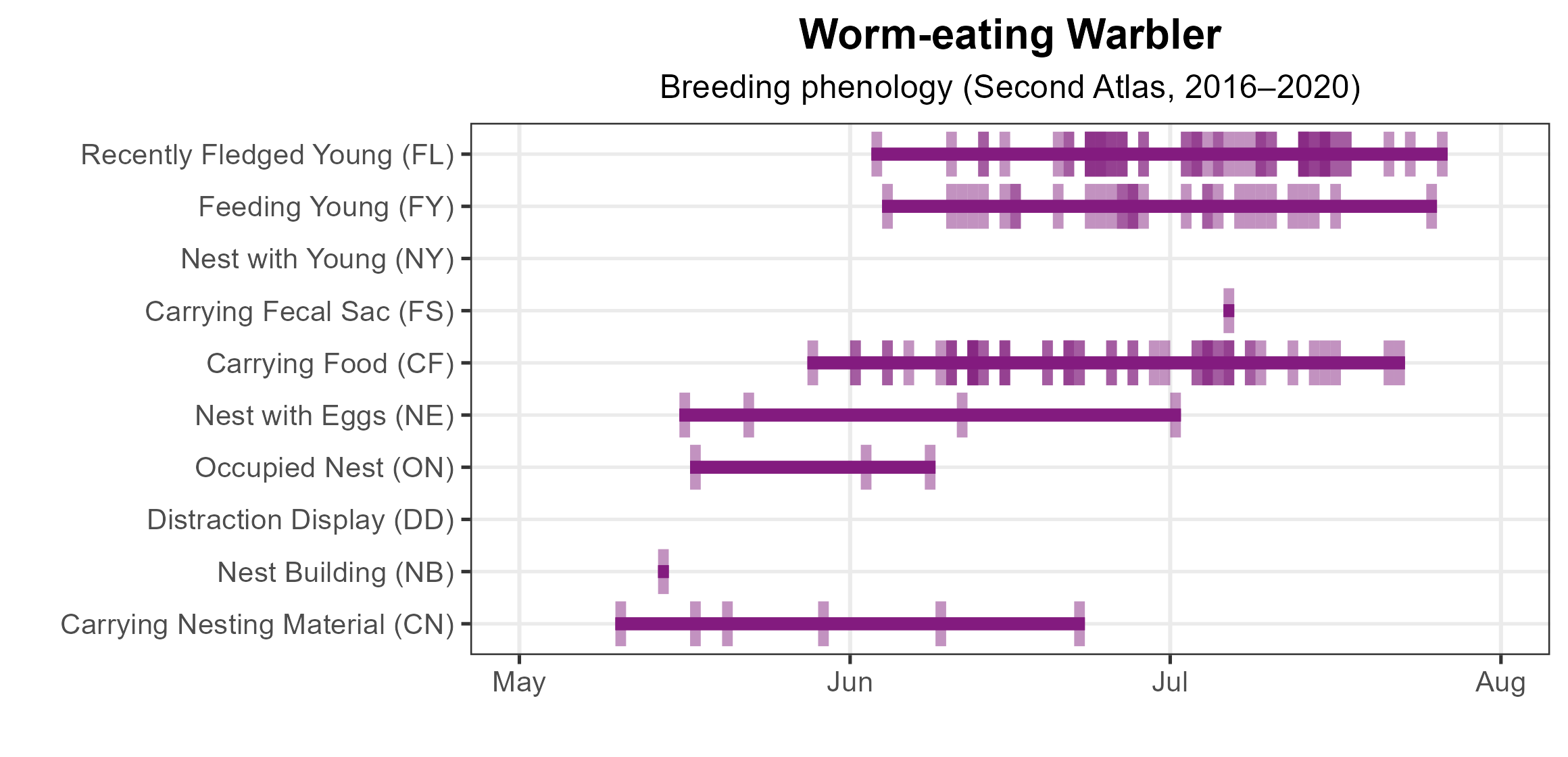

The earliest confirmed breeding behavior was recorded in early May, with birds carrying nest material as early as May 10, when many migrants are still moving through. Eggs were observed from May 16 to July 1. Breeding was documented through the last week of July. As ground-nesting birds, Worm-eating Warblers have nests that can be stumbled across and easily observed but typically only while hiking off-trail in unfavorable, steep terrain. Thus, few nests were found, and none were with young (Figure 6). For more general information on the breeding habits of the Worm-eating Warbler, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Worm-eating Warbler breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Worm-eating Warbler breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Worm-eating Warbler phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

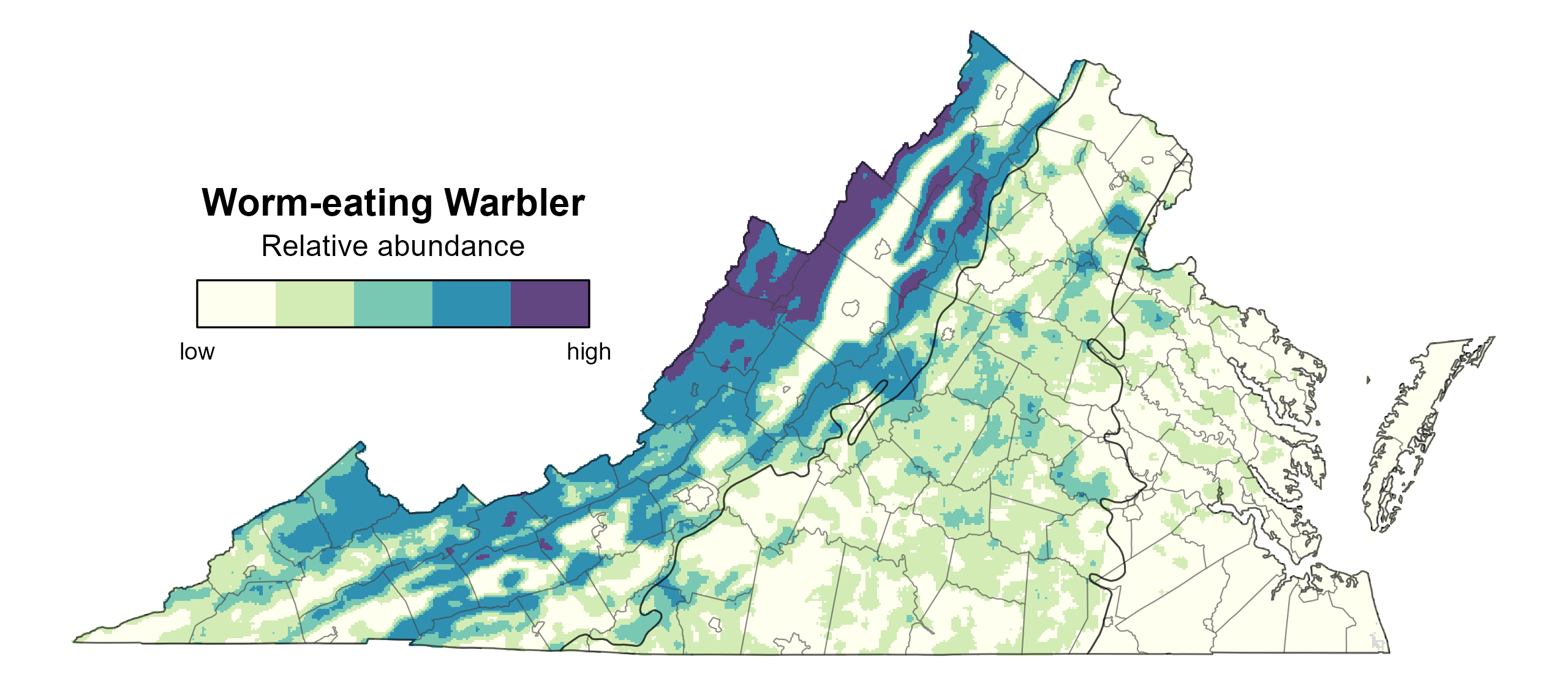

Worm-eating Warbler relative abundance was estimated to be highest in the northern Mountains and Valleys region, particularly along the border with West Virginia and in the Blue Ridge Mountains (Figure 7).

The total estimated Worm-eating Warbler population in the state is 138,290 individuals (with a range between 81,167 and 240,082). However, North American Breeding Bird Survey data do not produce credible trends in Virginia or the region, so no population trend is available.

Figure 7: Worm-eating Warbler relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Conservation

Because populations are apparently stable in Virginia, Worm-eating Warblers are not a species of concern. They are considered area-sensitive, forest-interior specialists, so forest fragmentation is likely to reduce their breeding populations. The large, rarely disturbed forests in the Mountains and Valleys region present valuable protected habitat. At the same time, active management of forests is important to maintain habitat quality for forest-dwelling birds. Timber harvest and prescribed fire temporarily eliminate suitable habitat, but local declines immediately after these management practices typically reverse within three years (Vitz et al. 2020).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Ruhl, P. J., K. F. Kellner, J. M. Pierce, J. K. Riegel, R. K. Swihart, M. R. Saunders, and J. B. Dunning, Jr. (2018). Characterization of Worm-eating Warbler (Helmitheros vermivorum) breeding habitat at the landscape level and nest scale. Avian Conservation and Ecology 13:11. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-01185-130111.

Vitz, A. C., L. A. Hanners, and S. R. Patton (2020). Worm-eating Warbler (Helmitheros vermivorum), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.woewar1.01.