Introduction

The Vesper Sparrow is named after its song, which continues into the evening after many other birds go quiet. Its scientific name emphasizes its habitat preferences: Pooecetes gramineus translates literally to “grass dweller, fond of grass,” but the habitats used by Vesper Sparrows consist of more than just grass. They like open areas with sparse grasses, some bare ground, and some shrubs. In the eastern U.S., this can include old fields, crop and hay fields, meadows, and other weedy areas, including mountain balds (Jones and Cornely 2020). In Virginia, Vesper Sparrows are uncommon during migration and winter but are rare to locally abundant breeders in a few select areas of the state (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007).

Breeding Distribution

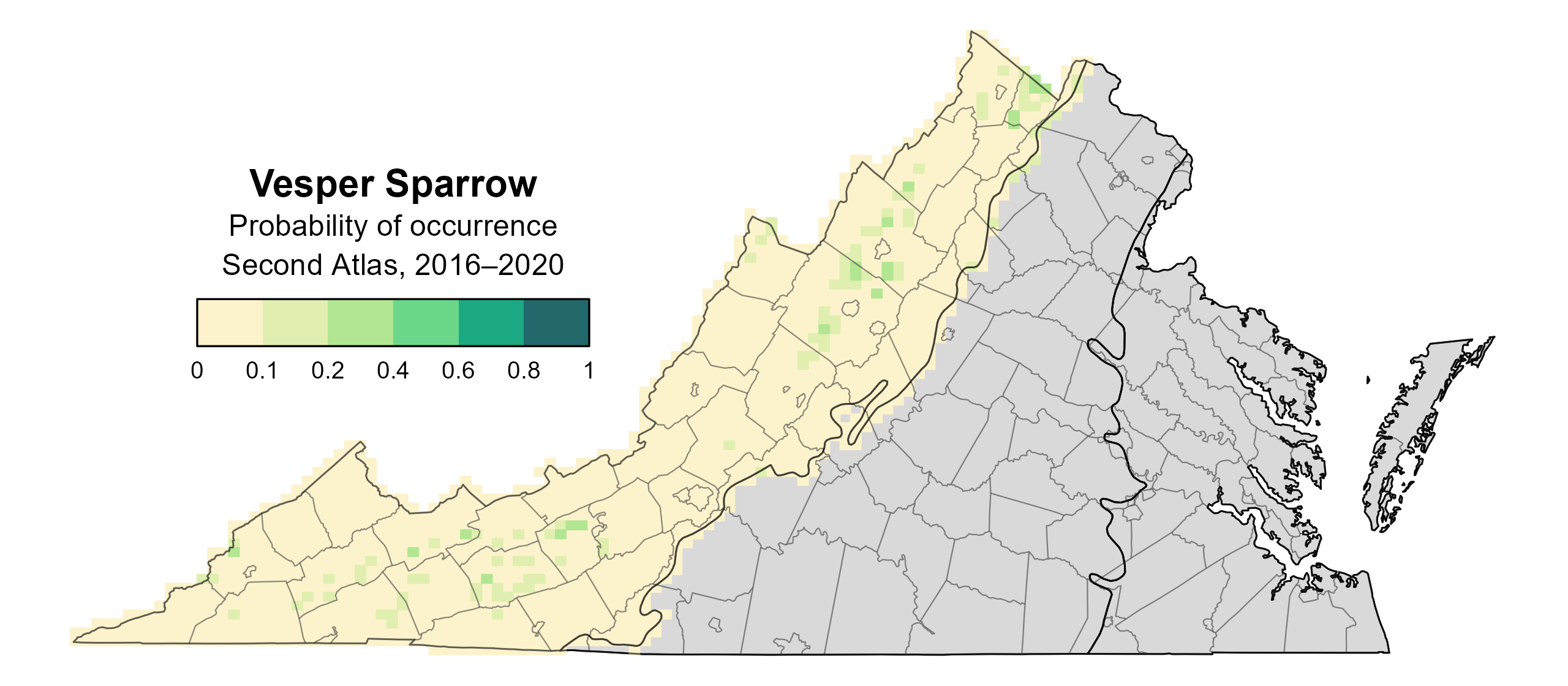

The Vesper Sparrow is patchily distributed in the eastern U.S., and its Virginia population represents an extension along the Appalachians that terminates in the Great Smoky Mountains (Jones and Cornely 2020). Thus, in Virginia, this species is only found in the Mountains and Valleys region, and its distribution is limited within that region. It is most likely to occur in northern Clarke County near the West Virginia border, in the Shenandoah Valley, and at a few sites in the valleys and mountain balds of southwestern Virginia (Figure 1). Although breeding was observed at a few sites outside this region (see Breeding Evidence), its distribution in other regions could not be modeled.

The likelihood of Vesper Sparrow occurrence decreases with the proportion of forested or developed cover in a block. Overall, the species is rare, and the highest predicted likelihood of occurrence in a block is only 36%.

Due to breeding data limitations, its distribution during the First Atlas and the change between Atlas periods could not be modeled. For more information on its occurrence during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Vesper Sparrow breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

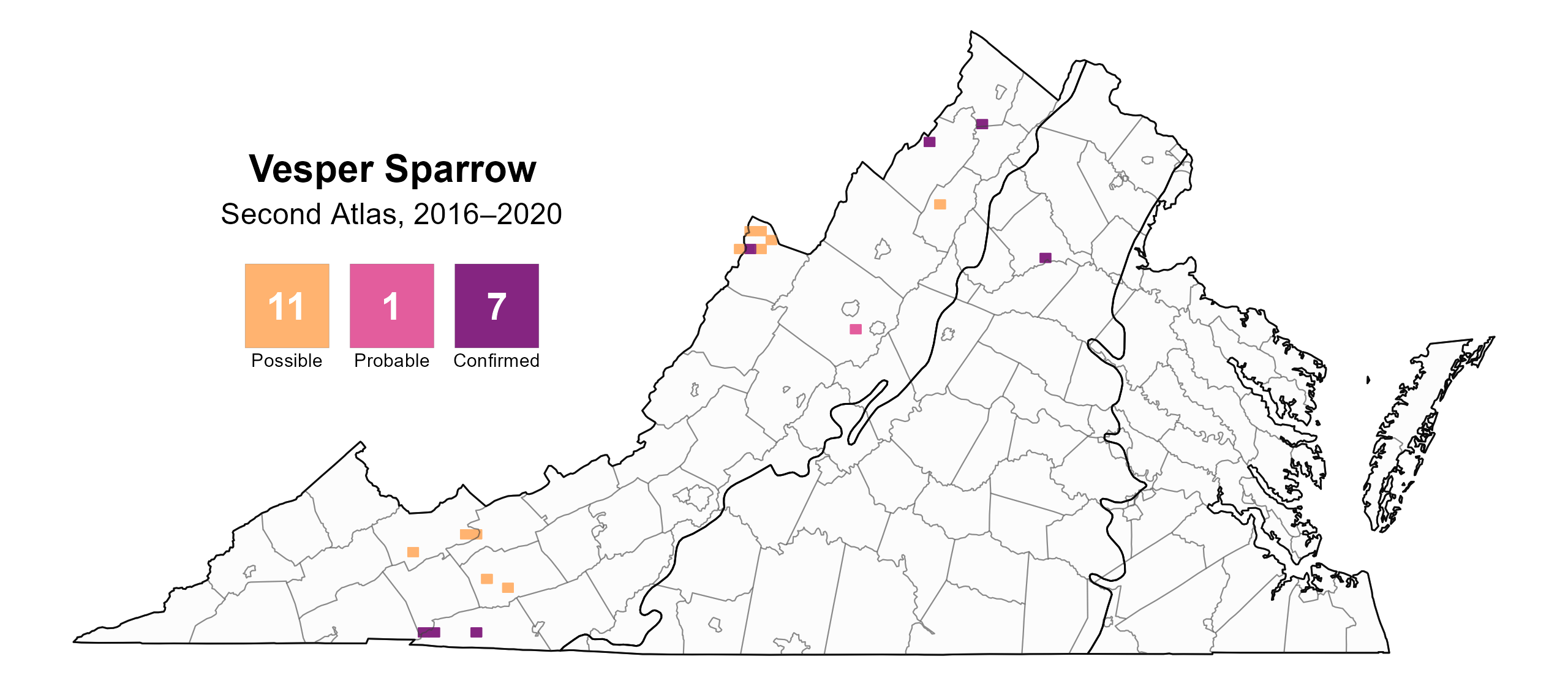

Vesper Sparrows were confirmed breeders in seven blocks and six counties (Figure 2). In the Mountains and Valleys region, they were confirmed breeders in Middletown (Frederick County), in Alonzaville (Shenandoah County), along Bear Mountain Road (Highland County), at Whitetop Mountain, in Grayson Highlands State Park, and in the town of Independence (Grayson County).

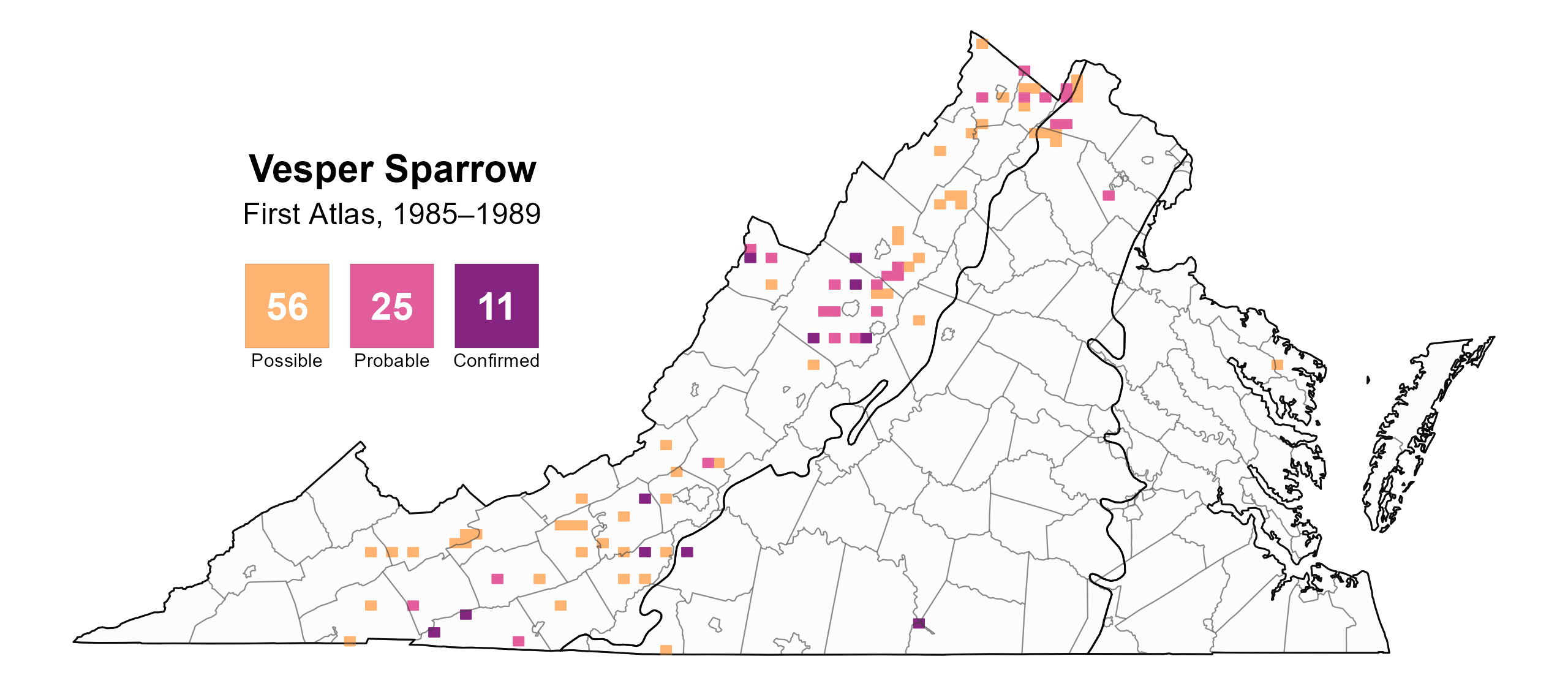

The only confirmed breeding location in the Piedmont region was near the Rapidan River (Culpeper County). Vesper Sparrow was additionally a probable breeder north of Stuarts Draft (Augusta County). Despite greater survey effort during the Second Atlas, fewer breeding confirmations were recorded than during the First Atlas (Figures 2 and 3), suggesting that the species’ footprint within the Commonwealth is decreasing because of broader declines within the Appalachian region (see Population Status).

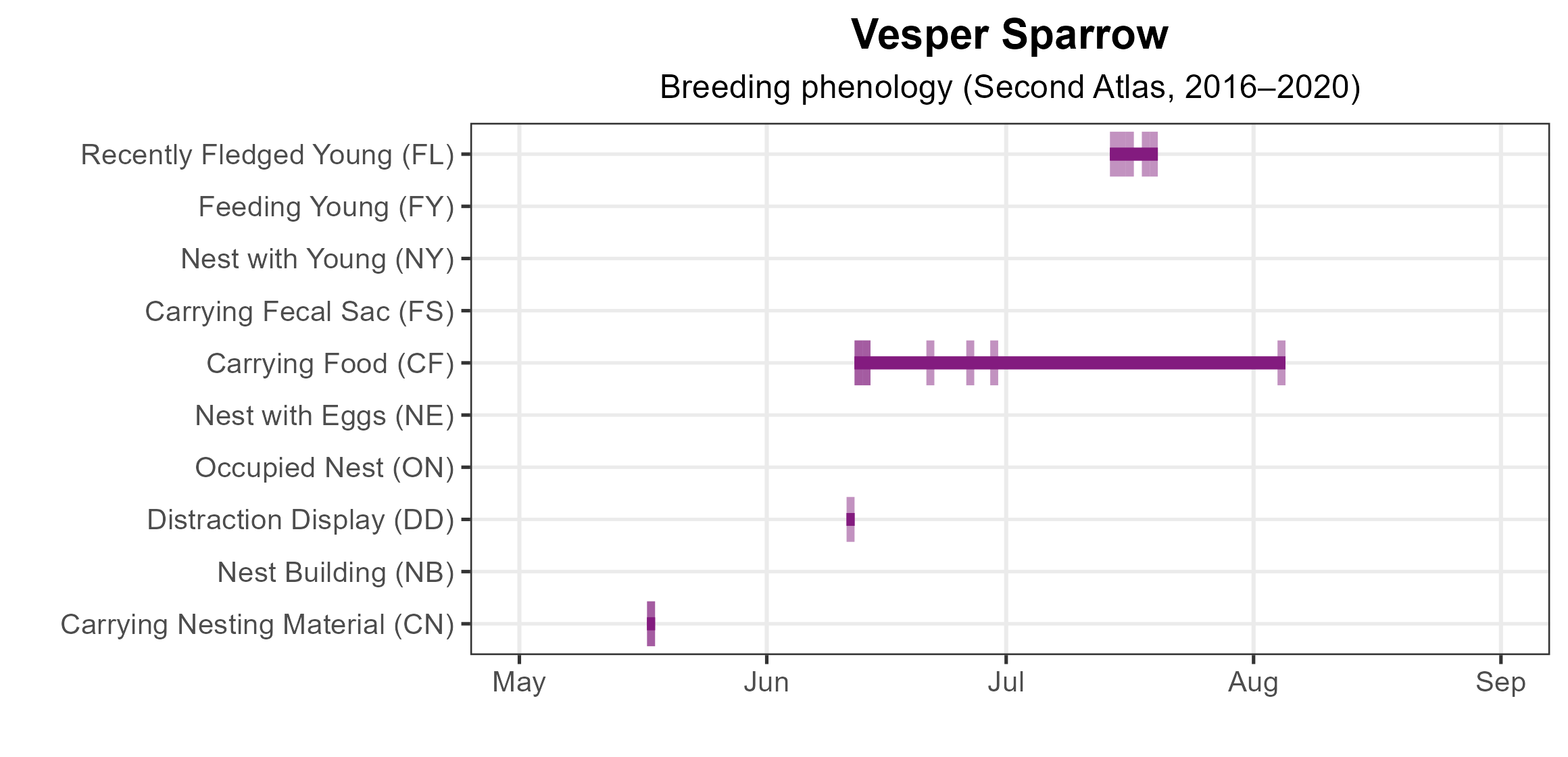

No nests were located during the Second Atlas, with most breeding evidence consisting of adult behaviors. Breeding was confirmed from May 17 (carrying nesting material) through August 4 (carrying food) (Figure 4). Dependent fledglings were noted between July 14 and 19 and included an observation of young using a bean field. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Vesper Sparrow, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Vesper Sparrow breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Vesper Sparrow breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Vesper Sparrow phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

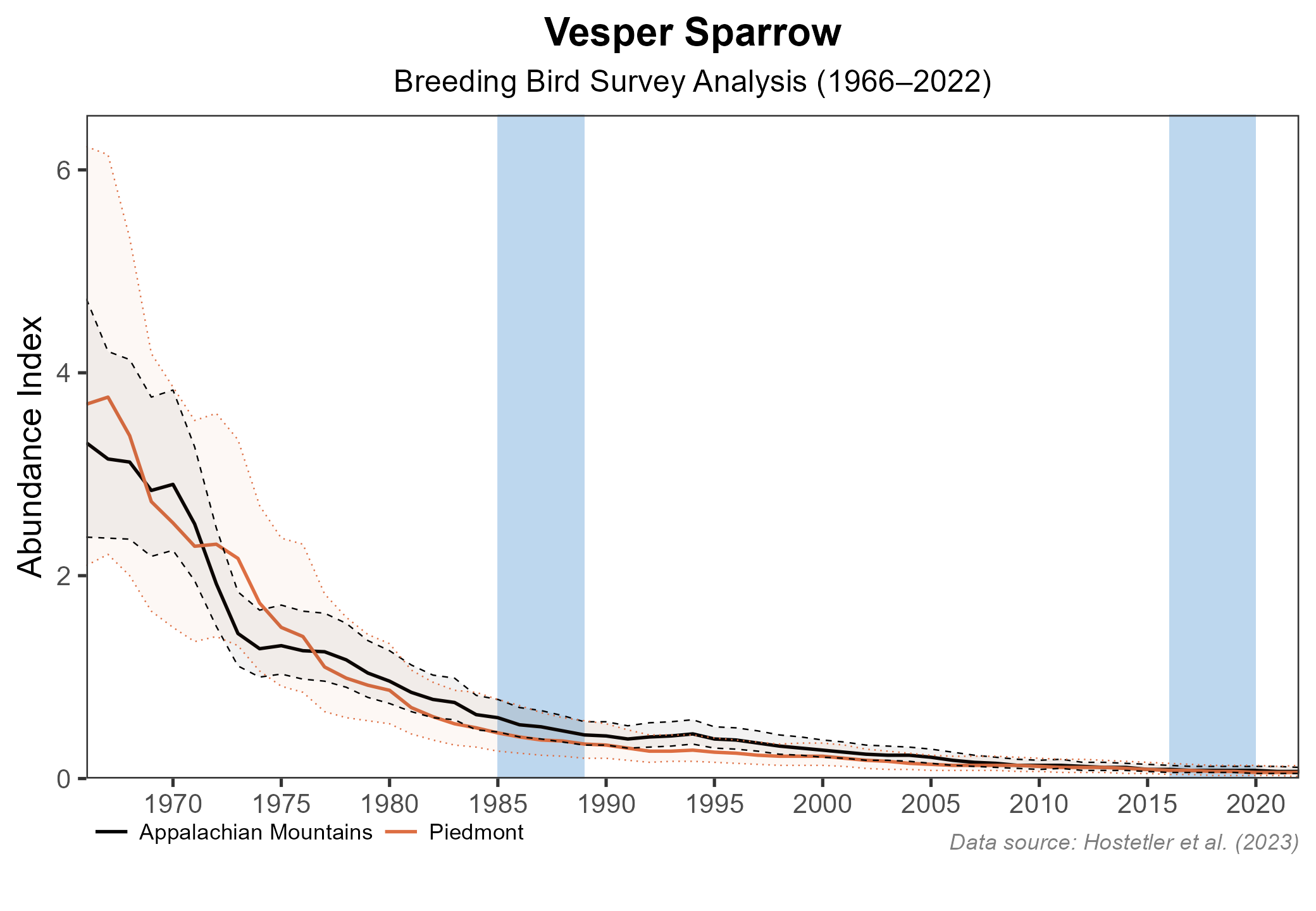

Vesper Sparrow populations have declined in Virginia. Abundance could not be modeled from Atlas point count data because the species is so rare, and the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) does not cover the species well in the state for the same reason. The BBS trend for the Piedmont region showed a significant decrease of 7.18% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 5). Between the First and Second Atlases, BBS data also showed a substantial decline, with a decrease of 5.34% per year in this region from 1987–2018.

Figure 5: Vesper Sparrow population trend for the Piedmont as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Due to its small population size and steeply declining trend, the Vesper Sparrow is classified as a Tier I Species of Greatest Conservation Need in the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan, indicating that it is of critical conservation need and extremely vulnerable to extirpation in the state (VDWR 2025). Although suitable habitat was likely present prior to European colonization, the species expanded into the northeastern U. S. and Canada via large-scale clearing of forests for farming in the 1800s; thus, farm abandonment and reforestation since the 1940s may be the primary cause of the species’ decline in the Northeast (Jones and Cornely 2020).

In Virginia, although its current range is mostly west of the Blue Ridge Mountains, confirmation of breeding in the northern Piedmont suggests that the species may be more broadly distributed. Multiple Atlas records from Whitetop Mountain and surrounding areas may point to a concentration of the species in that area, where it may be associated with high-elevation balds. Vesper Sparrow is known to breed in reclaimed surface mines in neighboring states such as Pennsylvania and West Virginia (Bailey and Rucker 2021; Jones and Cornely 2020), and the value of these habitats to the species in Virginia should also be investigated. Relatively little is known about Vesper Sparrow breeding ecology within the Commonwealth, including the extent to which breeding populations and wintering populations share the same individuals. Insights into any potential connections could prove valuable to their conservation.

Currently, in the state, conservation of Vesper Sparrow falls under a larger umbrella of grassland bird conservation rather than species-specific actions. Intensive farming practices such as earlier first harvests and more frequent harvests per year are a major threat to nesting Vesper Sparrows, as for all grassland birds (Jones and Cornely 2020). Actions taken to conserve more common nesting grassland species, particularly the Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus Savannarum), could benefit this species as well (Ruth 2015). The Virginia Grassland Bird Initiative is putting science into practice by offering research-based best management practices and incentive programs targeted at the broader grassland bird community. Beyond efforts targeted at pastures and hayfields, the role of high-elevation habitats (both natural and human-altered) in supporting the species needs additional attention.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Bailey, R. S., and C. B. Rucker (Editors) (2021). The second atlas of breeding birds in West Virginia. The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA, USA. 568 pp.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Jones, S. L., and J. E. Cornely (2020). Vesper Sparrow (Pooecetes gramineus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.vesspa.01.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Ruth, J. M. (2015). Status assessment and conservation plan for the Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus Savannarum), version 1.0. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Lakewood, CO, USA.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.