Introduction

A common migrant but secretive breeder at high elevations, the Veery has a muted cinnamon body that contrasts with its distinctive veer song, which resonates through the forest. Over its broader breeding range, this species prefers second-growth broadleaf forests with a dense, wet understory, within which it nests (Hecksher et al. 2020). In the Southern Blue Ridge region, which makes up a portion of its range in Virginia, its breeding habitat is typically at high elevations in northern hardwood forests composed of beech (Fagus grandifolia), birch (Betula spp.), and maple (Acer spp.) (Dettmers et al. 2002).

Additionally, the Veery is considered area-sensitive, meaning it relies on large, unbroken areas of forest (Hecksher et al. 2020). Its impressive migratory flights between South America and its breeding grounds have been studied by researchers who found that its movements are predictive of the Atlantic fall hurricane season; in years with severe seasons, Veeries ended their breeding season early to depart for their wintering grounds (Heckscher 2018).

Breeding Distribution

The Veery is primarily a northern breeder, and its presence in Virginia represents a southern range extension along the Appalachian Mountains through to northern Georgia (Hecksher et al. 2020). It also is restricted to the Mountains and Valley region in Virginia. Although Veeries breed at high elevations, they are not elevation-sensitive in that their presence does not increase with increasing elevation (Lessig 2008). In Virginia, they are typically found above 3,000 ft (914 m) (Figure 1). However, they have been recorded in areas as low as 1,750 ft (533 m) in Bath County (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). Elevation is the best predictor of Veery occurrence, with Veeries being more likely to be found in blocks at higher elevations.

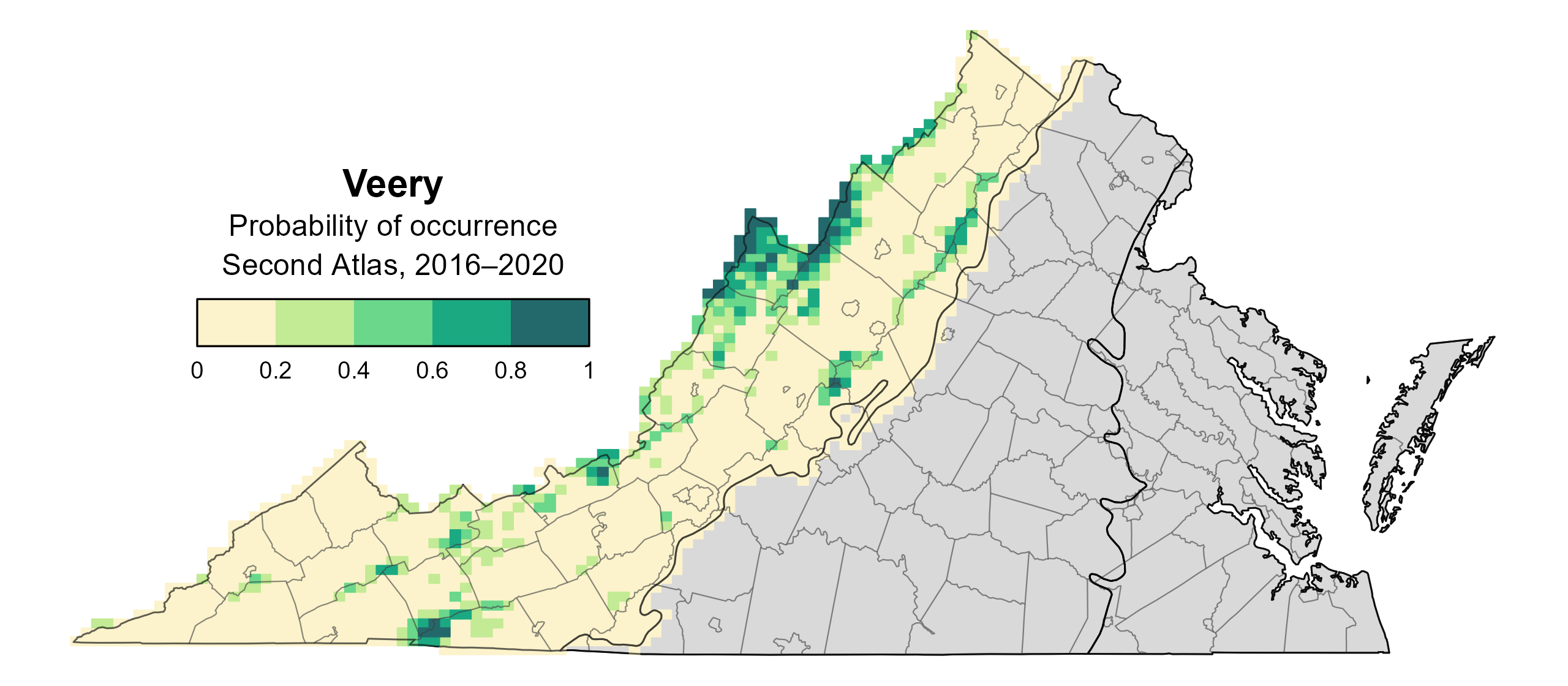

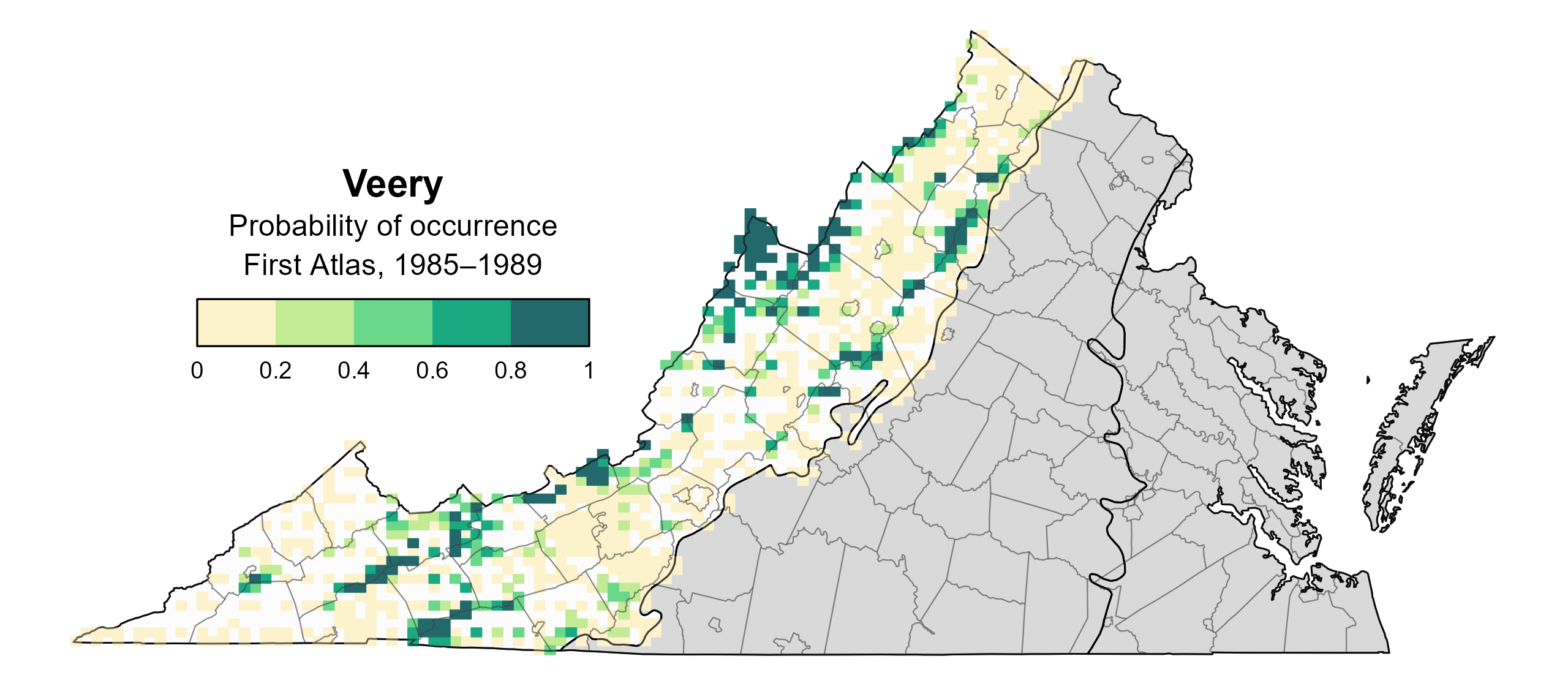

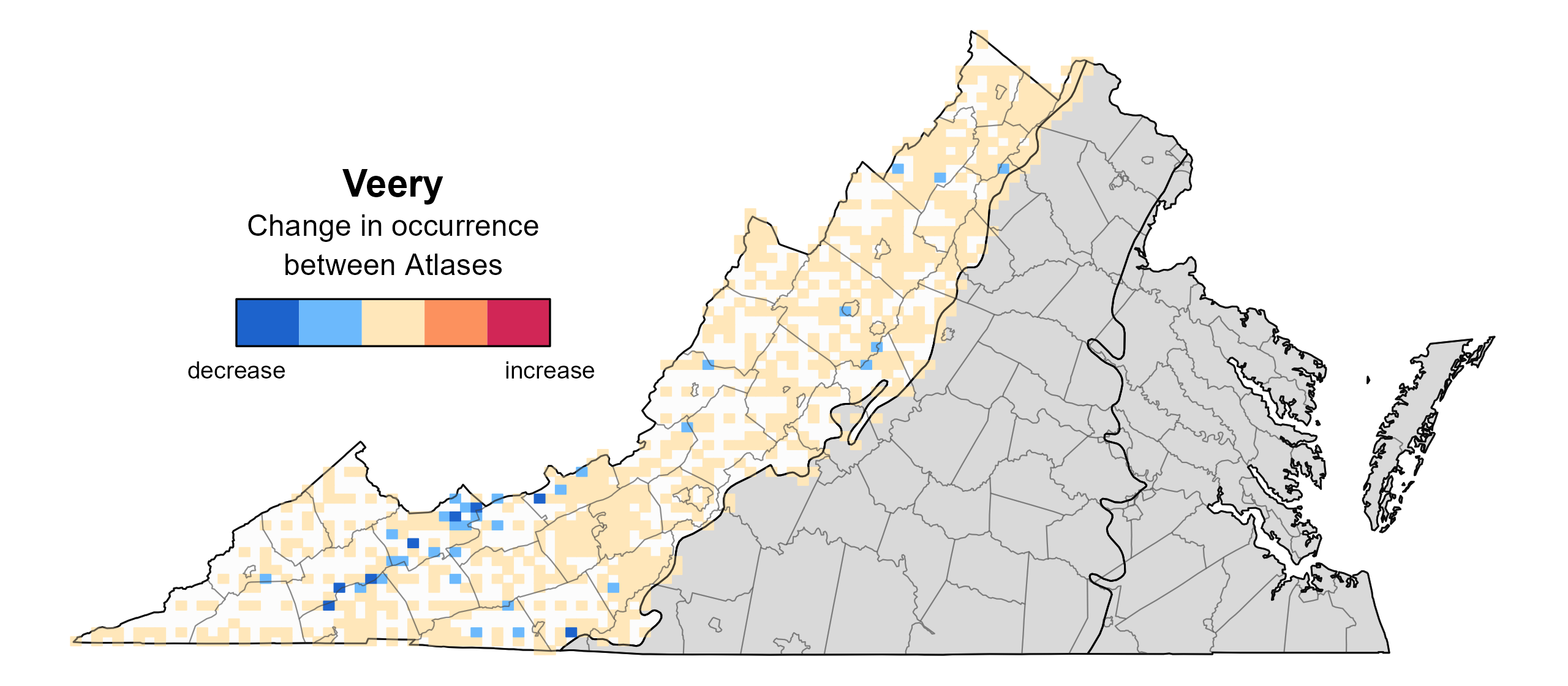

The Veery’s likelihood of occurrence in the Second Atlas was similar to that in the First Atlas (Figures 1 and 2), with the greatest probable occurrence concentrated along mountain ridges. The likelihood of Veeries being found in any particular block remained relatively constant between Atlas periods, except in several counties in the southwestern portion of the Mountains and Valleys region where it decreased slightly (Figure 3).

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Veery breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 2: Veery breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Veery change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

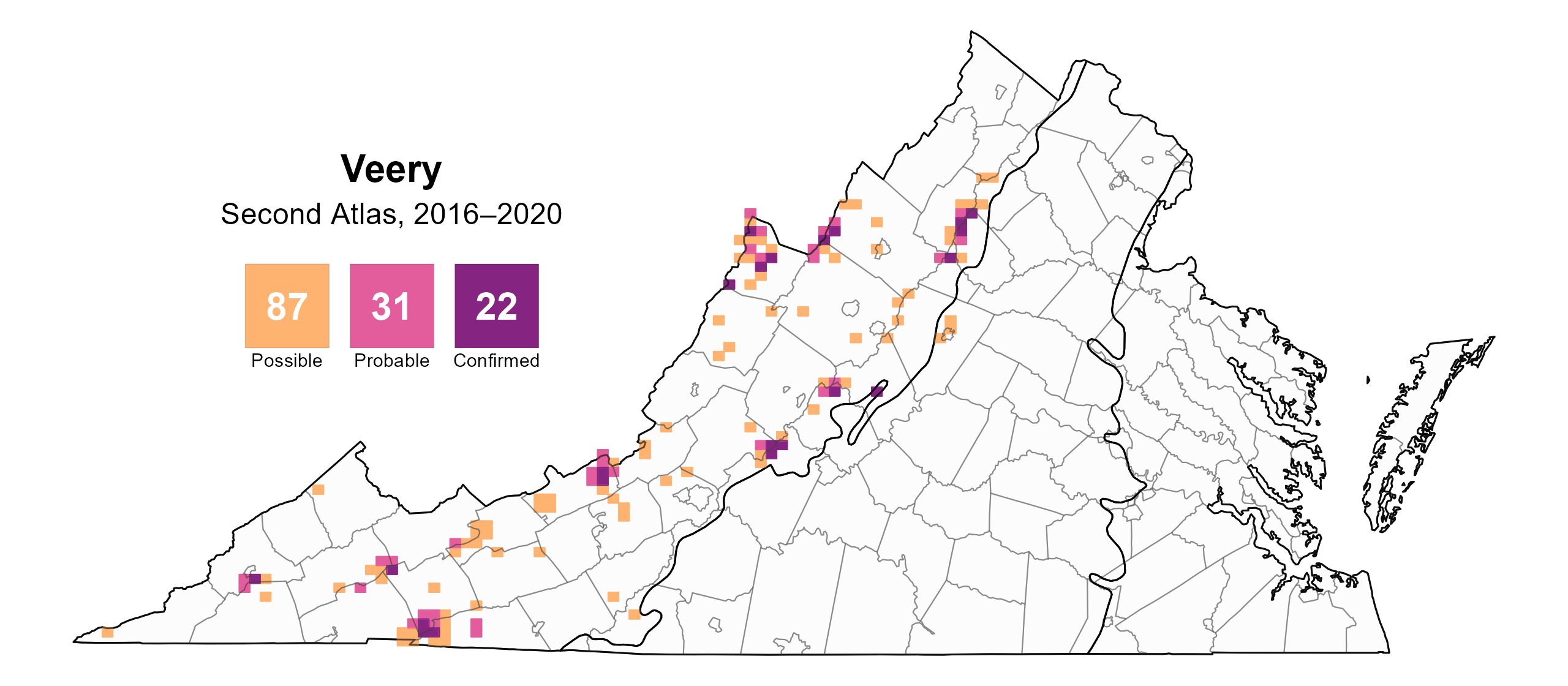

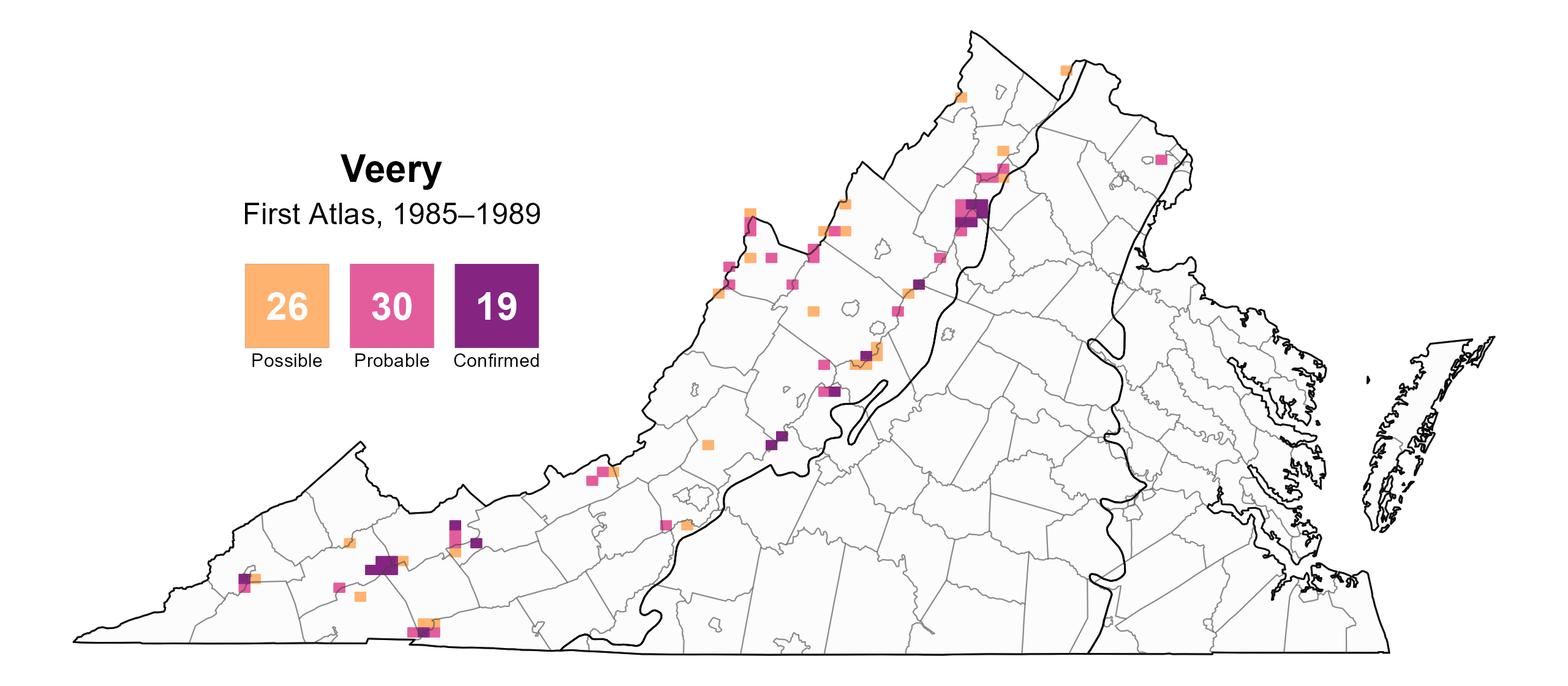

The Veery was a confirmed breeder in only 22 blocks and 12 counties and a probable breeder in an additional 31 blocks and seven counties; all observations were within the Mountains and Valleys region (Figure 4). The pattern of breeding evidence was similar between Atlases, although the species was categorized as a probable breeder in one block in Fairfax County during the First Atlas based on observations of singing birds at the same location over one week apart (Figure 5). Although breeding has not been confirmed, Veery has been hypothesized to be a likely breeder in northern Fairfax County, where it has been reported as a rare and irregular summer visitor (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007).

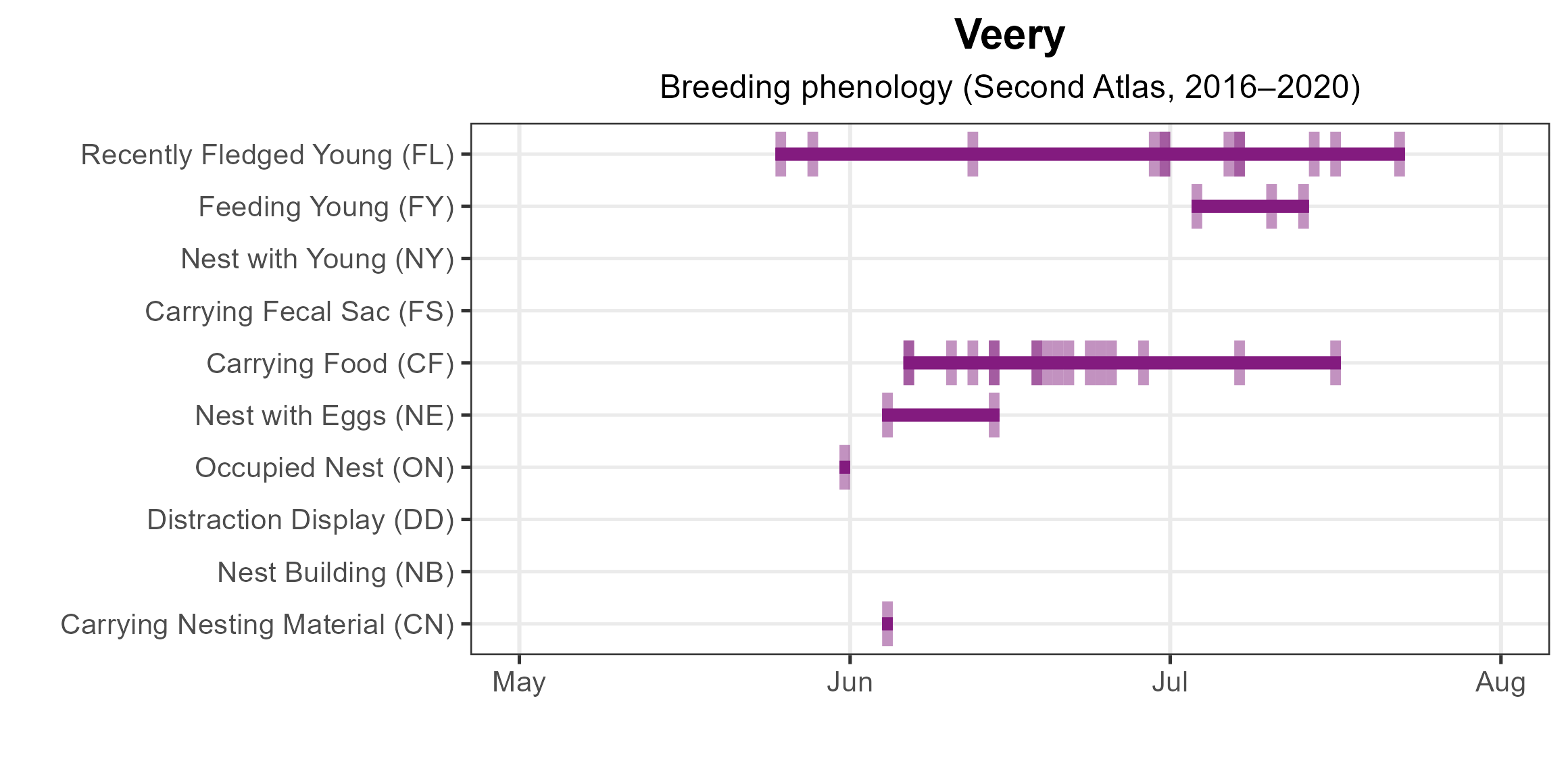

Most breeding confirmations were of adults carrying food or observations of recently fledged young (May 25 to July 22), as Veery nests are typically located on or near the ground in dense understory shrubs and are therefore hard to locate (Hecksher et al. 2020; Figure 6). For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Veery breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Veery breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Veery phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

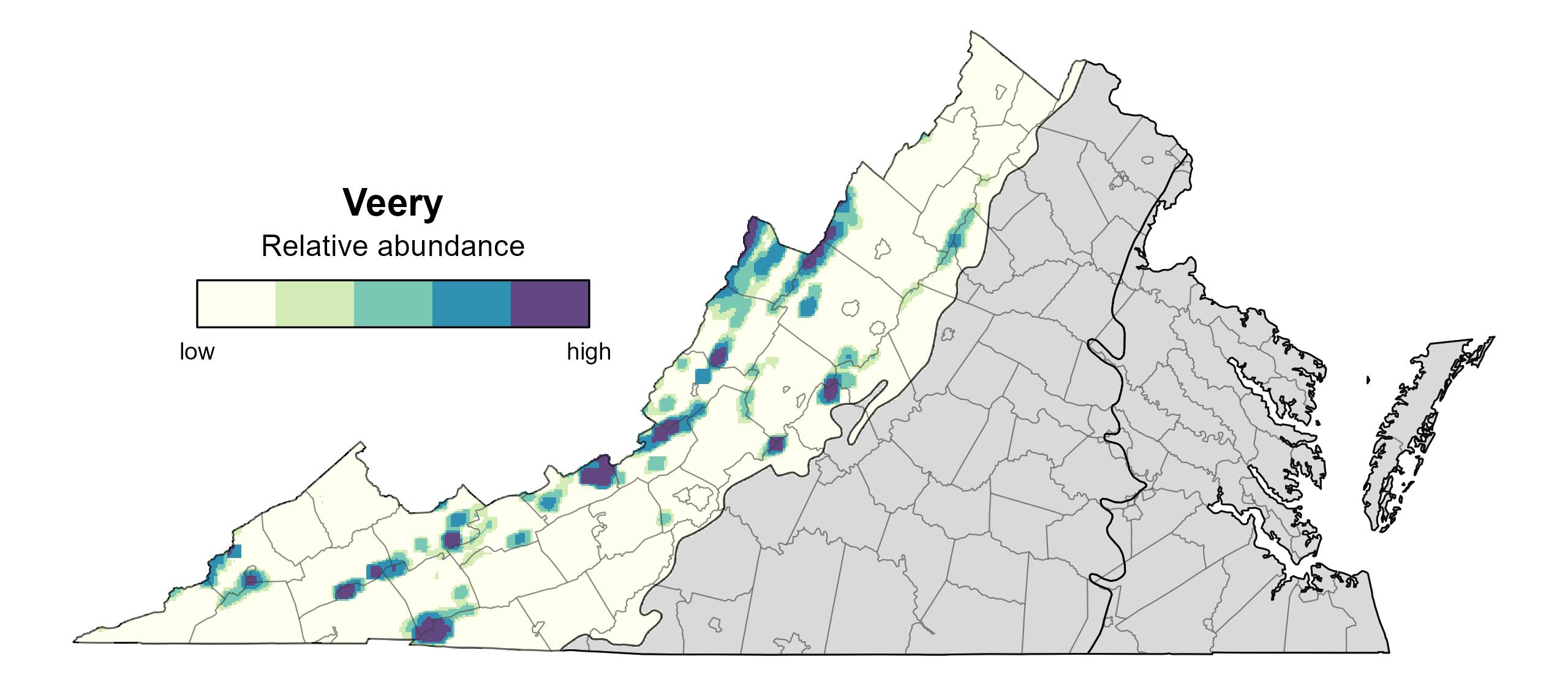

Veery relative abundance was estimated to be highest on slopes and ridges in the Mountains and Valleys region, specifically along the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains (Figure 7). Abundance was particularly high in the vicinity of Mount Rogers (Grayson and Smyth Counties) and Mountain Lake (Giles County) and along the ridgeline at the West Virginia border in Highland and Rockingham Counties.

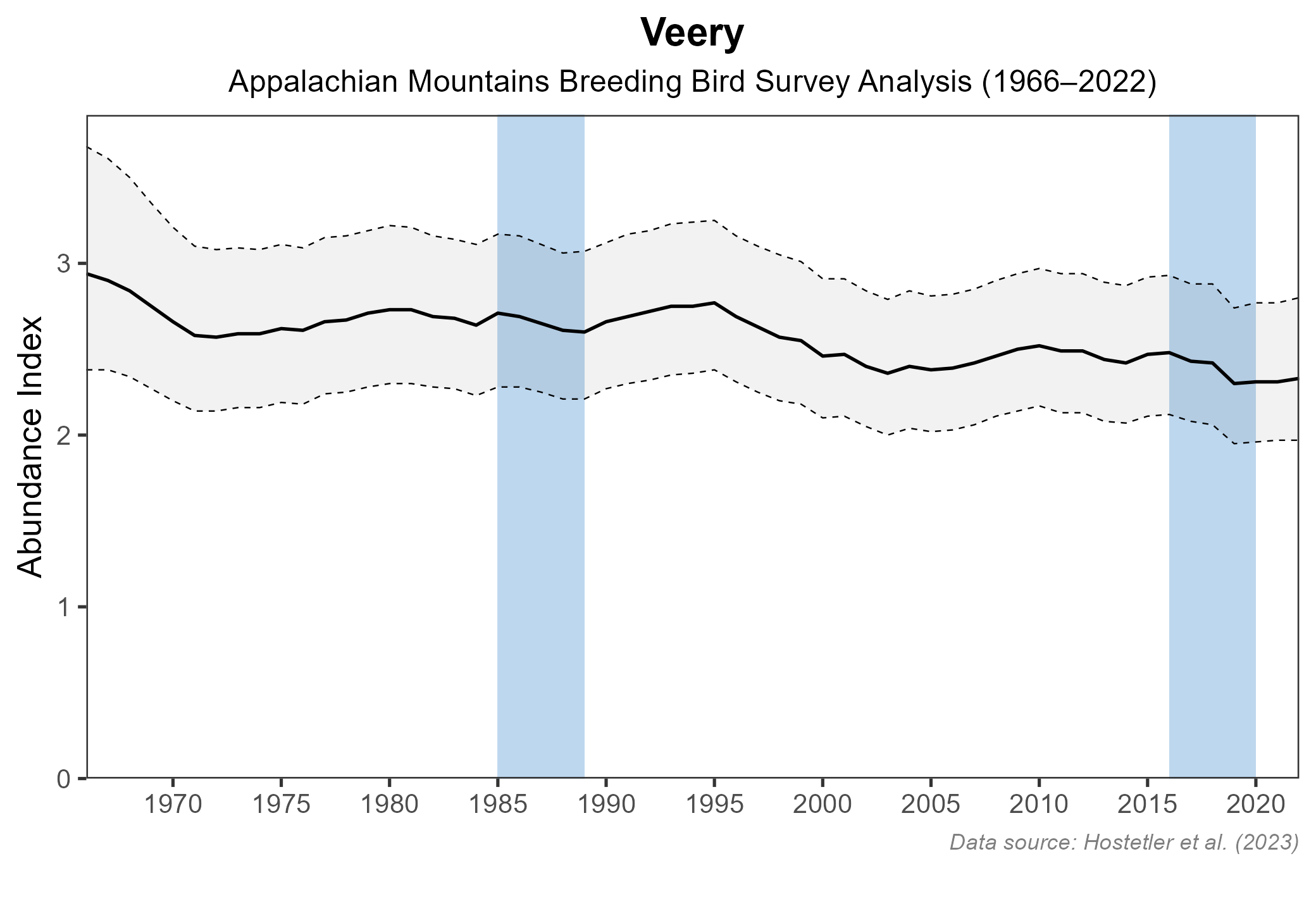

The total estimated Veery population in the state is approximately 77,000 individuals (with a range between 31,000 and 212,000). The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) coverage in the Veery’s breeding range in Virginia is limited; however, the BBS trend for the Appalachian Mountains region showed a significant decrease of 0.41% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 8). Between Atlas periods, the Veery population decreased by a nonsignificant annual 0.28% from 1987–2018.

Figure 7: Veery relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high. Areas in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 8: Veery population trend for the Appalachian Mountains as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Based on ongoing declines in the state, the Veery is included in the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan as a Tier III Species of Greatest Conservation Need (High Conservation Need) (VDWR 2025). Its distribution within the Mountains and Valleys region is somewhat restricted, but the species is not uncommon in suitable habitats. A 2005–2007 survey of high-elevation bird communities found Veery at 33 out of 37 sites and at 55% of over 1,000 points surveyed (Lessig 2008), with its distribution mirroring that predicted based on Second Atlas data (Figure 1).

The reasons for the Veery’s declines are unclear. As an area-sensitive species, it may be susceptible to the effects of forest fragmentation on its breeding grounds; however, it may also benefit from the proximity of areas with dense forest understory for nesting to open forested areas for foraging (Heckscher 2018). Identifying and implementing forest management practices that meet these diverse habitat needs would benefit the species.

Research on the Veery’s habitat needs and overall ecology on its wintering grounds is also needed. The species overwinters in the Amazon basin of South America, where tracking data from eastern and western breeding populations shows mid-winter movements from south-central Brazil to a second set of wintering sites, mostly north of the Amazon River (Heckscher 2018). Loss of forest habitat to agriculture and development, as well as the potential impact of hydroelectric dams on the flood cycle of the Amazon River, may be contributing to population losses of the Veery. A better understanding of where Appalachian breeders spend the winter could help target research to sites that are critical to the Virginia population of the species.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Dettmers, R., D. A. Buehler, and K. E. Franzreb (2002). Testing habitat-relationship models for forest birds of the Southeastern United States. The Journal of Wildlife Management 66):417–424. https://doi.org/10.2307/3803174.

Heckscher, C. M. (2018). A nearctic-neotropical migratory songbird’s nesting phenology and clutch size are predictors of accumulated cyclone energy. Scientific Reports 8:9899. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28302-3.

Heckscher, C. M., L. R. Bevier, A. F. Poole, W. Moskoff, P. Pyle, and M. A. Patten (2020). Veery (Catharus fuscescens), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.veery.01.

Lessig, H. (2008). Species distribution and richness patterns of bird communities In the high elevation forests of Virginia. Master’s Thesis. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.