Introduction

A familiar sight in marshes during fall and winter, the Swamp Sparrow disappears from all but a select few areas of Virginia in the breeding season. In fact, the first breeding confirmation of the species in the state since 1965 was in 2004 at Mulberry Point Marsh on the Rappahannock River near Warsaw (Watts et al. 2008). Generally, Swamp Sparrows breed in freshwater and brackish marshes with low, dense vegetation (Herbert and Mowbray 2020). In Virginia, the small numbers of birds breeding in the mountains belong to the subspecies Melospiza georgiana georgiana, which breeds in freshwater marshes. Birds in the Coastal Plain belong to the subspecies M. g. nigrescens, which breeds in tidal fresh and brackish marshes of the Mid-Atlantic Coast, reaching the southern end of its range in the Virginia portion of the Chesapeake Bay (Herbert and Mowbray 2020).

Breeding Distribution

Because the species is rare, its distribution could not be modeled. For information on where Swamp Sparrows occur in Virginia, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

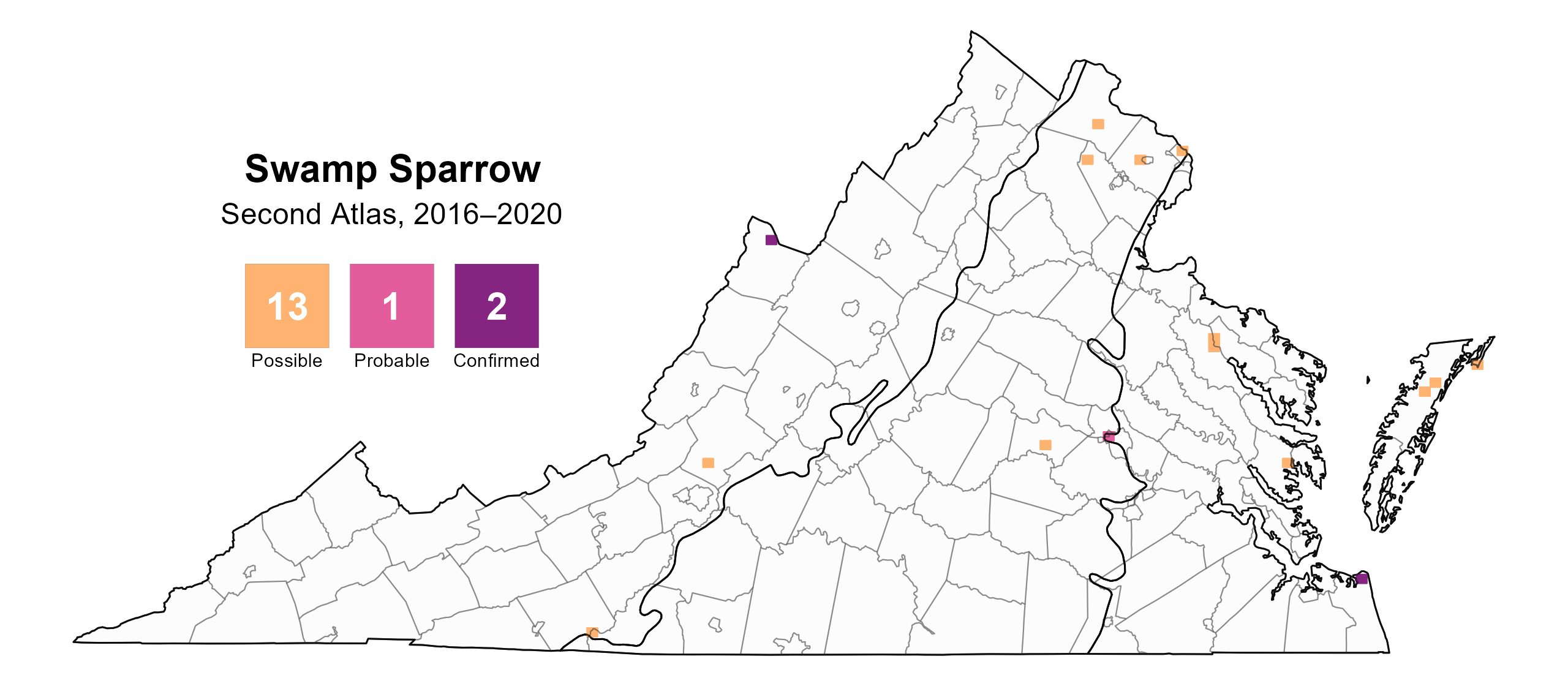

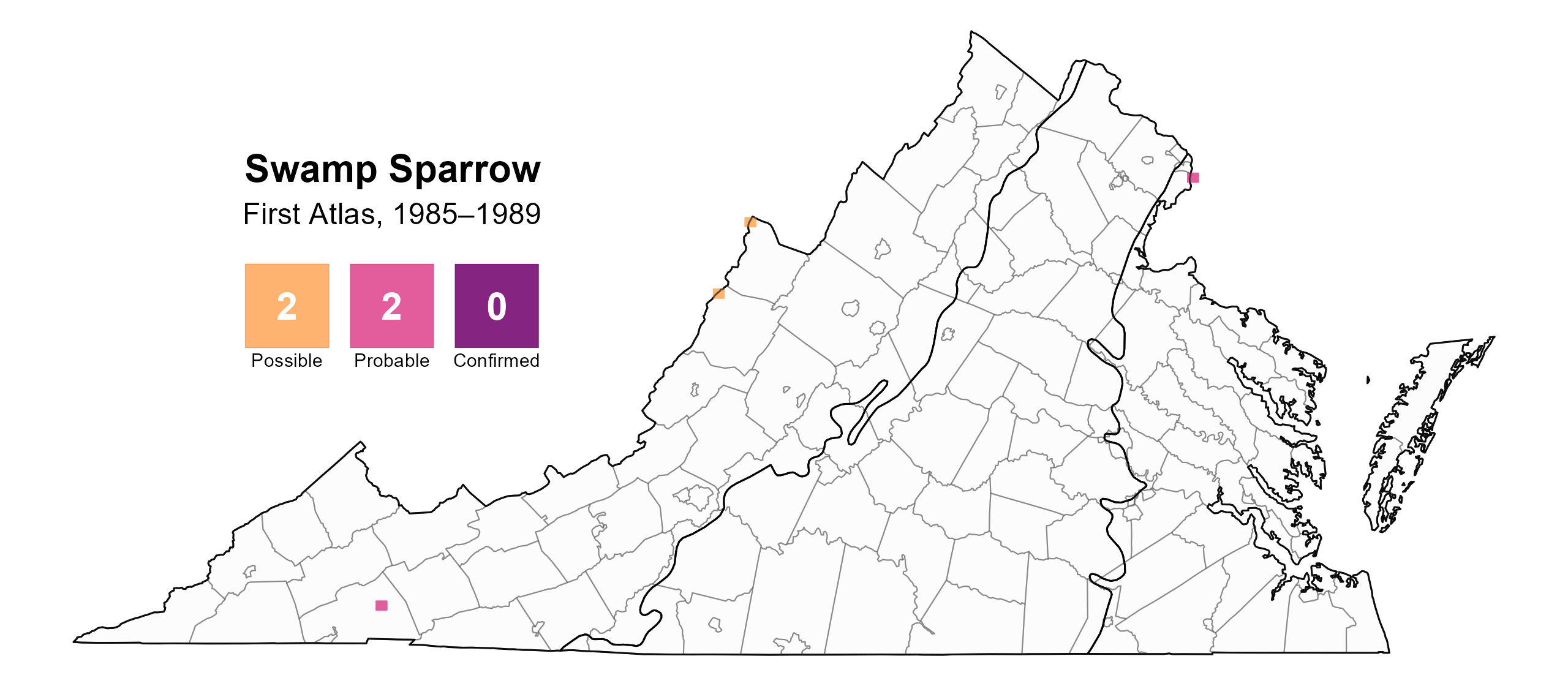

The Swamp Sparrow was a confirmed breeder in two blocks with one block in Highland County and one block in the city of Virginia Beach, and it was a probable breeder in the city of Richmond (Figure 1). During the First Atlas, the species was not confirmed breeding, but breeding was probable at Dyke Marsh in Fairfax County and in Washington County (Figure 2), with possible breeders in Bath and Highland Counties.

In the Mountains and Valleys region, a bird was confirmed breeding (carrying food) at Rainbow Springs Retreat in Highland County. Two instances of possible breeding were observed at Botetourt Center at Greenfield (Botetourt County) and Orchard Gap (Carroll County).

Although breeding could not be confirmed in the Piedmont region, there were several records of Swamp Sparrows as possible breeders during summer at Fort C.F. Smith Park (Arlington County), the Fairfax County Government Center (Fairfax County), the Dulles Greenway Wetlands (Loudoun County), and the Regency Golf Course Nature Trail (Prince William County), and further south at Shelton’s Fire Road (Powhatan County).

More Swamp Sparrows were observed in the Coastal Plain than in any other region. The only breeding confirmation in this region was at First Landing State Park in Virginia Beach. There was an additional probable record at James River Park (city of Richmond). The species was considered a possible breeder at multiple other locations. Populations of up to 13 singing birds were observed at Mulberry Point Marsh along the Rappahannock River (Richmond County). As noted, the Rappahannock is home to a relatively recently discovered population of the Coastal Plain Swamp Sparrow that may be more extensive than previously thought but has mostly flown under the radar (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007; Watts et al. 2008). There was one possible breeder in Gloucester County and multiple records of singing birds in northern Accomack County, including on Chincoteague Island.

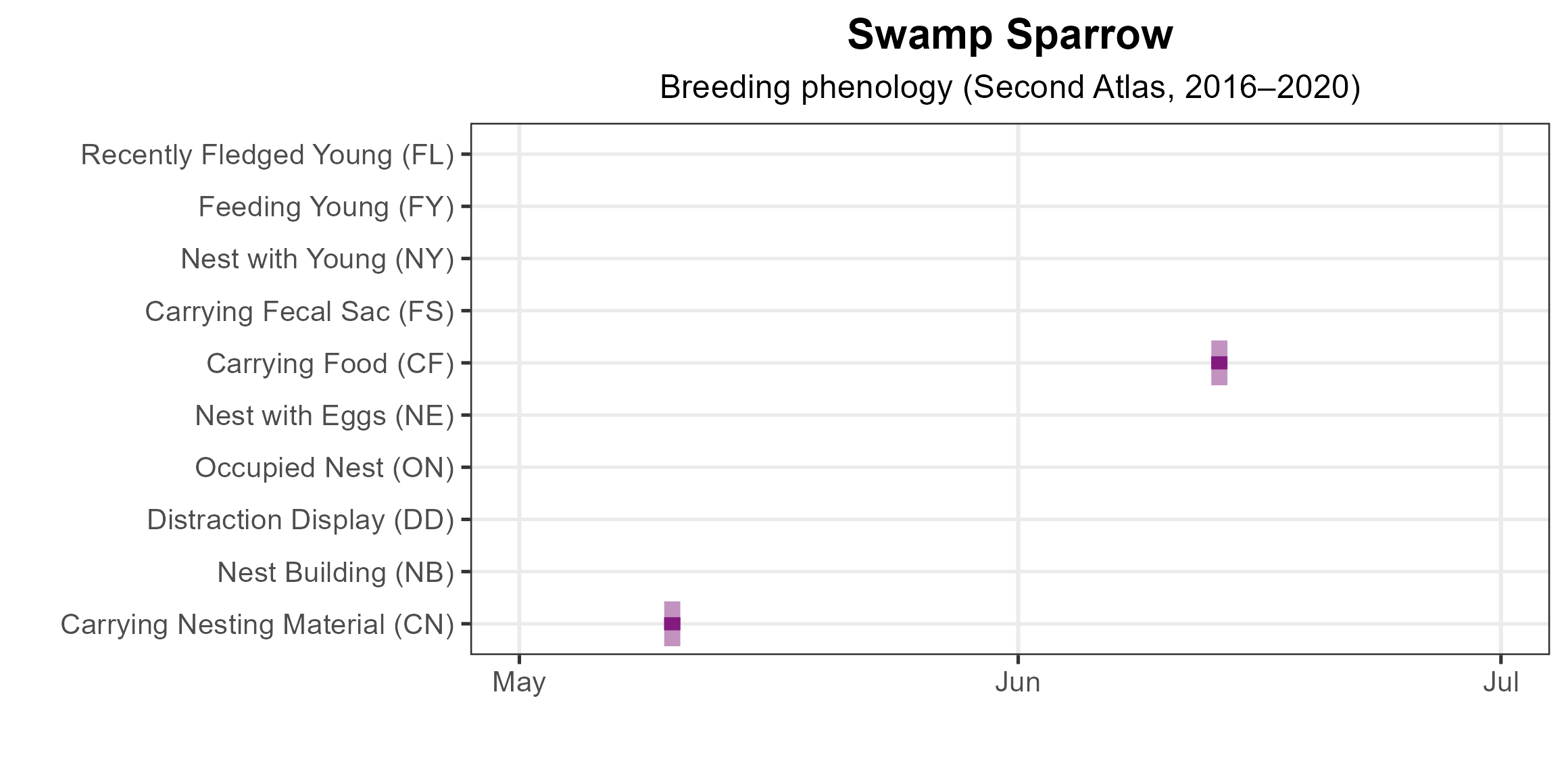

Because the species was so seldomly observed, it is difficult to describe their breeding phenology. The bird in Virginia Beach was carrying nesting material on May 10, and the bird in Highland was carrying food on June 13 (Figure 3). For more general information on breeding habits, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Swamp Sparrow breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Swamp Sparrow breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Swamp Sparrow phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

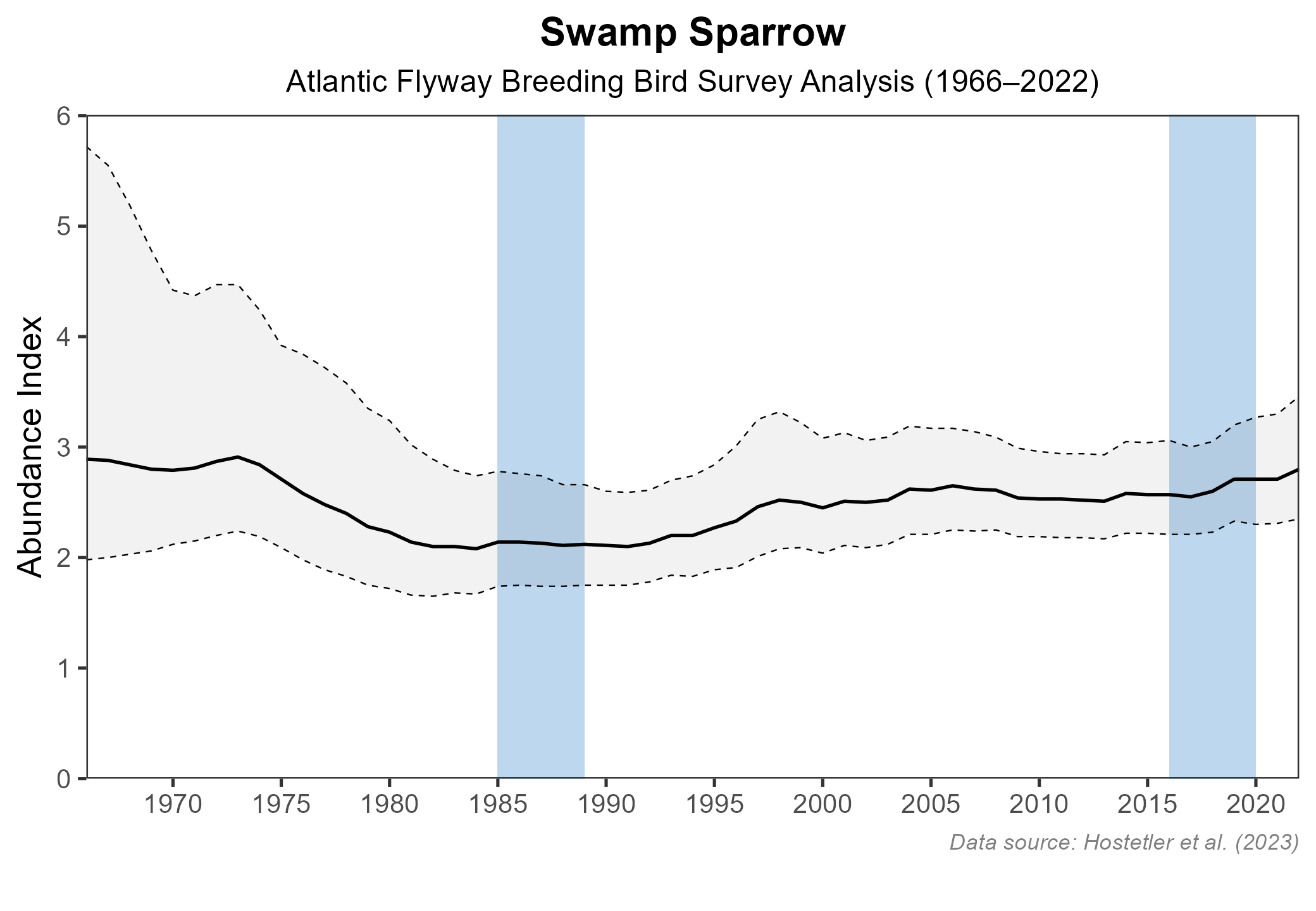

Abundance could not be modeled because the species is so rare that it was not detected during Atlas point count surveys. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) also does not cover the species well in Virginia, but the population trend for the Atlantic Flyway shows there was a nonsignificant decrease of 0.05% per year from 1966–2022 and a nonsignificant increase of 0.64% per year from 1987–2018 between Atlases (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 4).

Figure 4: Swamp Sparrow population trend for the Atlantic Flyway as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Relatively little is known about the distribution and population size of the Coastal Plain Swamp Sparrow in Virginia, and the Atlantic Flyway population trend is likely more representative of the nominate subspecies. This lack of data prevents assessment of the Coastal Plain Swamp Sparrow as a potential Species of Greatest Conservation Need. Therefore, it is included in the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan as an Assessment Priority Species, indicating the need for more information on its population status in the state (VDWR 2025).

Despite the dearth of data, it is believed that the Coastal Plain Swamp Sparrow subspecies may be more at risk than the inland subspecies. As residents of tidal marshes, Coastal Plain Swamp Sparrows are likely to be impacted by sea-level rise. Loss of low-salinity marshes to erosion and invasion by common reed (Phragmites australis) have been shown to reduce their breeding habitat (Herbert and Mowbray 2020). Additionally, the species as a whole is considered a “super collider” that is 176 times more likely to hit a building than the average bird species (Herbert and Mowbray 2020), so measures taken to reduce window collisions would disproportionately benefit Swamp Sparrows.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Herbert, J. A. and T. B. Mowbray (2020). Swamp Sparrow (Melospiza georgiana), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.swaspa.01.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Watts, B. D., M. D. Wilson, F. M. Smith, B. J. Paxton, and J. B. Williams (2008). Breeding range extension of the Coastal Plain Swamp Sparrow. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 120:393–395.