Introduction

The Savannah Sparrow’s buzzing song often blends into the background on its breeding grounds, which include grassy meadows, crop fields, and pastures (Wheelwright and Rising 2020). In Virginia, Savannah Sparrows are most common during migration and winter, particularly in the Coastal Plain (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). During the breeding season, however, the species is only found reliably in the Mountains and Valleys region. The Virginia breeding population falls within the southeastern edge of the species’ breeding range in the Appalachian Mountains, which extends as far south as Alabama.

Breeding Distribution

The first confirmed breeding record of Savannah Sparrow in Virginia was relatively recent, dating from 1973 in Highland County (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). This was followed by breeding confirmations in several other western counties, suggesting a range expansion into Virginia. Neighboring states may have been the source of this expanding population: summer records of the species in adjoining Maryland and West Virginia date back to the 1930s, with breeding first confirmed in West Virginia in 1934 (Bailey and Rucker 2021).

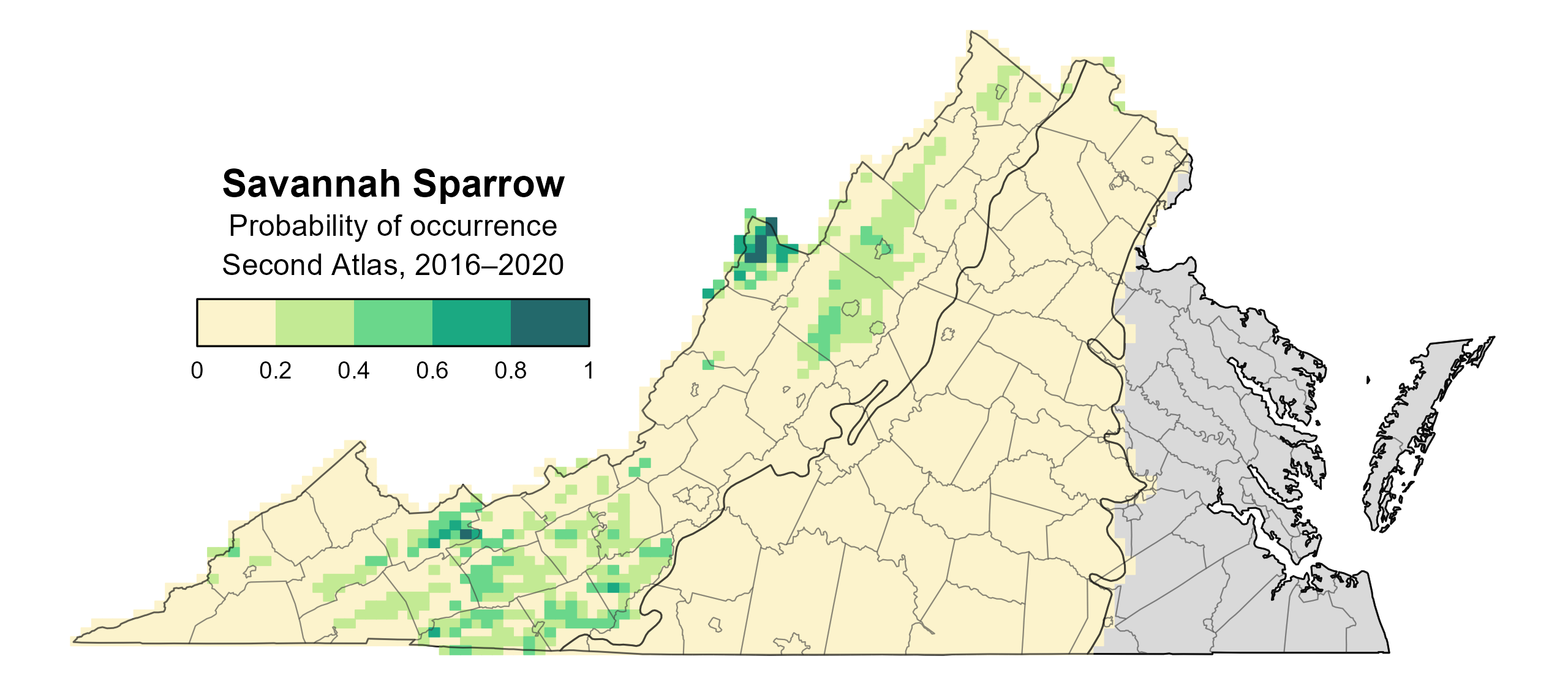

Currently, the Savannah Sparrow breeds primarily in the Mountains and Valleys region, where it is most likely to occur in Highland County, Burkes Garden in Tazewell County, and Mount Rogers in Grayson County (Figure 1). Although its range extends into the northern Piedmont region (see Breeding Evidence section), it has a much lower probability of being found there. Breeding was documented at a single site in the Coastal Plain region (see Breeding Evidence section), but its distribution in this region could not be modeled.

While the likelihood of Savannah Sparrow being found in a block grows with increasing elevation, it decreases in blocks with a high proportion of forest cover, underscoring the importance of open habitats in the Mountains and Valleys region to this species.

The Savannah Sparrow’s distribution during the First Atlas and the change between Atlas periods could not be modeled due to model limitations (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on its distribution during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Savannah Sparrow breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

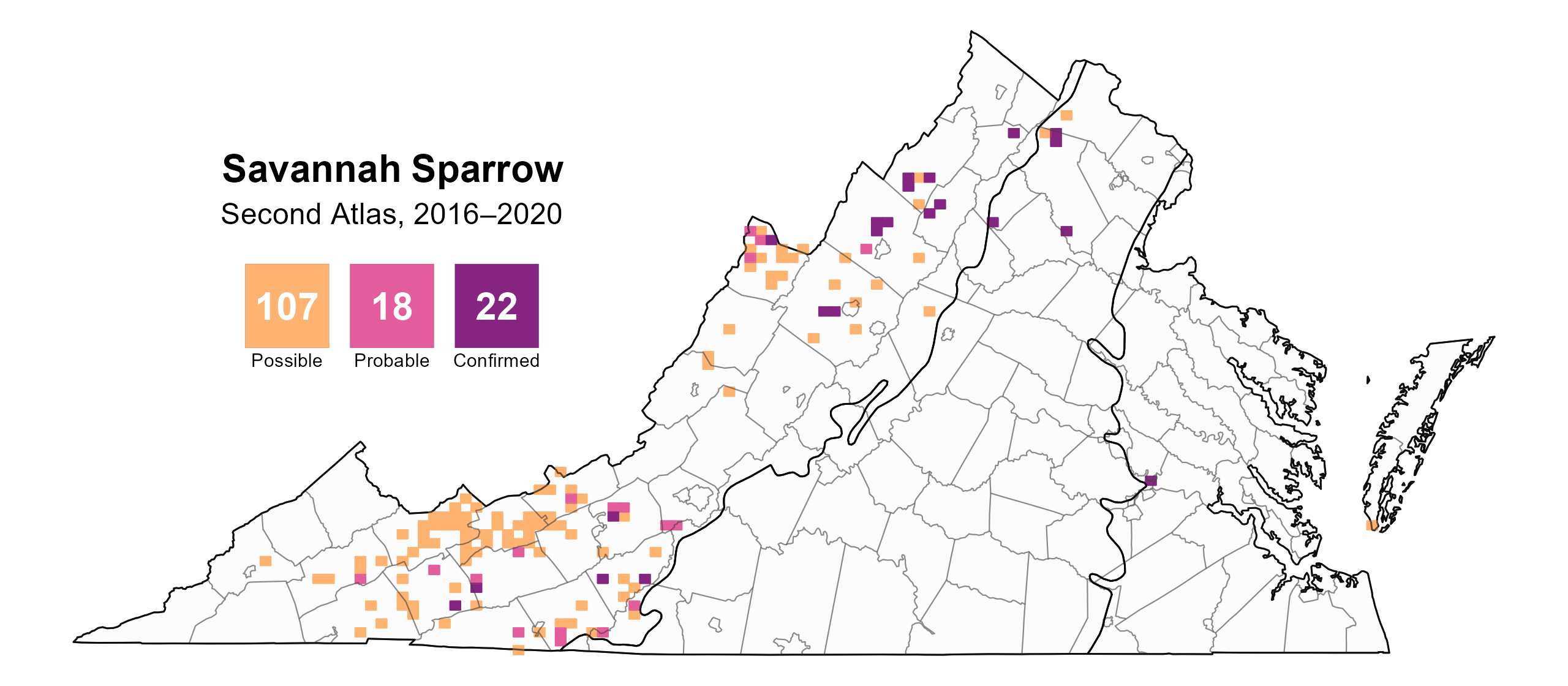

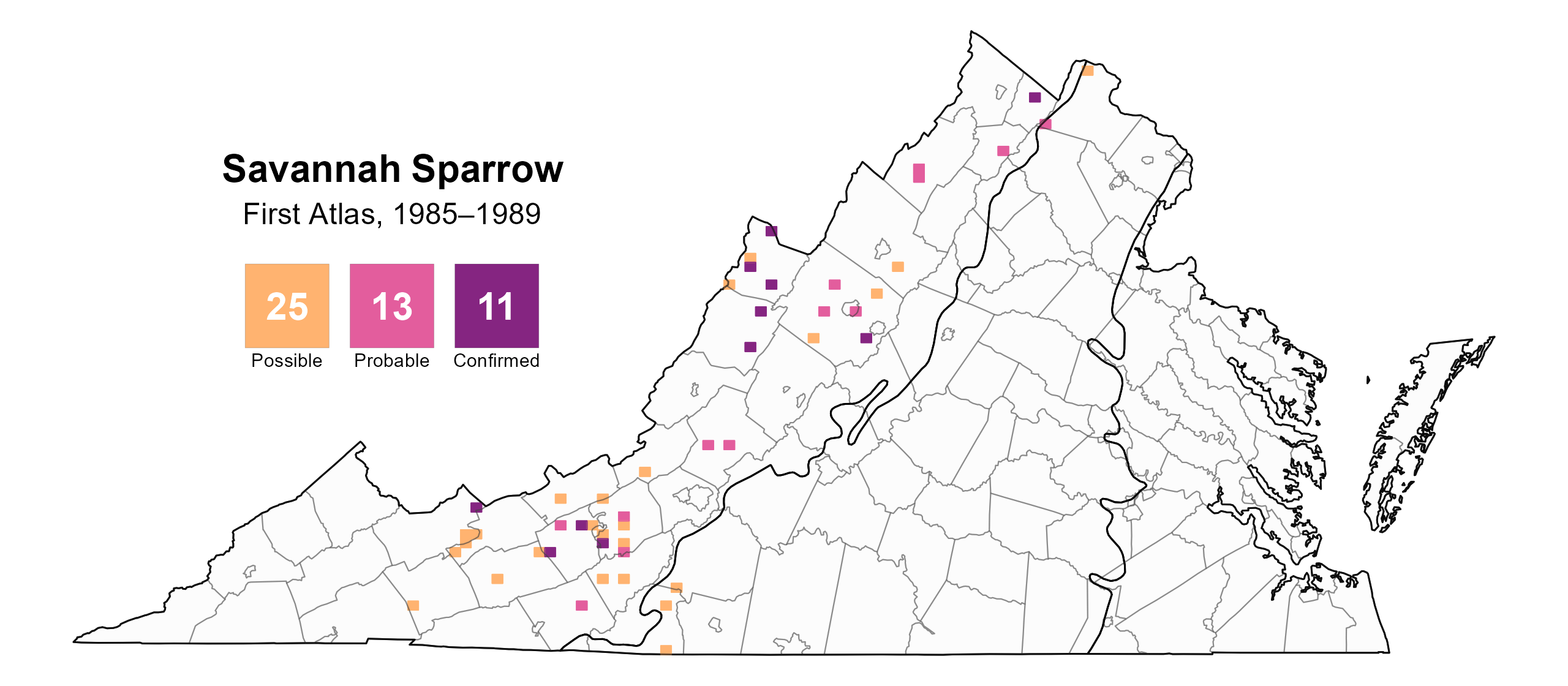

Savannah Sparrows were confirmed breeders in 22 blocks and 13 counties (Figure 2). It was a probable breeder in an additional 6 counties (Carroll, Giles, Grayson, Patrick, Roanoke, and Russell). An adult observed carrying food in early May at Shirley Plantation in Charles City County may represent the first confirmed breeding record of the species in Virginia’s Coastal Plain. Volunteers observed birds in the Mountains and Valleys region and at a limited number of sites in the Piedmont region during the First Atlas as well (Figure 3).

Nests were rarely documented, likely due to their well-hidden locations, and most breeding evidence consisted of fledglings or adults carrying food. Breeding confirmations were recorded from May 1 (carrying nesting material) through August 25 (recently fledged young) (Figure 4). An unusually late observation of two very recently fledged young with their parents on September 28 (Figure 4) in Wythe County strongly suggests that this was a second brood; the species is known to be double-brooded (Wheelwright and Rising 2020), though the late timing of the Wythe brood is still remarkable. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Savannah Sparrow, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Savannah Sparrow breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Savannah Sparrow breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Savannah Sparrow phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

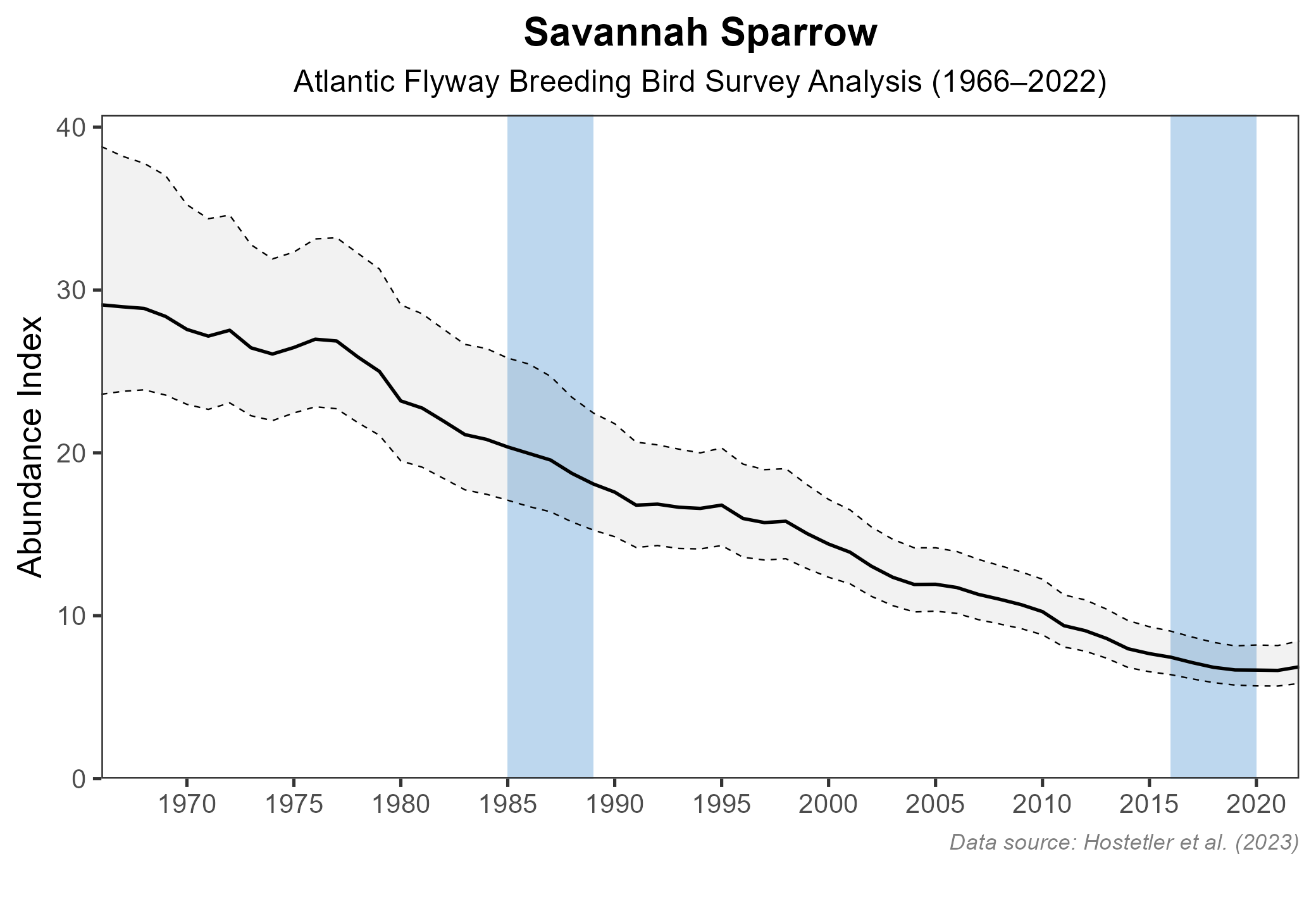

Savannah Sparrows were detected at only 28 points during Atlas point count surveys, and thus, abundance could not be modeled. Similarly, the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) does not cover the species well in the state and therefore does not produce a credible population trend for Virginia. However, the species is known to have declined regionally, with the BBS trend for the Atlantic Flyway region showing a significant annual decrease of 2.55% from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 5). Between the First and Second Atlases, BBS data showed an even steeper decline in this region, with a significant decrease of 3.34% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 5: Savannah Sparrow population trend for the Atlantic Flyway as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Both breeding and wintering Savannah Sparrows are included as Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) in the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan (VDWR 2025). The latter is a subspecies known as the Ipswich Sparrow, which is mostly confined to breeding on Cape Sable Island in Nova Scotia but winters along the sandy dunes of the Mid-Atlantic, including Virginia’s Eastern Shore. It is classified as a Tier I (Critical Conservation Need) SGCN, for which Virginia plays a significant conservation role by supporting a large proportion of the wintering population of what is an extremely range-restricted breeder (Hines et al. 2020; VDWR 2025). The Virginia breeding population of Savannah Sparrow, largely confined to the Mountain and Valleys region, is identified as a Tier II (Very High Conservation Need) SGCN in recognition of its population decline and relatively small population (VDWR 2025).

A conservation priority for the species within the Commonwealth is to better understand the size and true distribution of its breeding population. While not rare, Savannah Sparrows are far less common than more abundant grassland species such as Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum). In a 2017‒2018 grassland bird survey of eight counties in western Virginia, researchers at West Virginia University detected Savannah Sparrow at only 12% of over 1,000 points (Chris Lituma, unpublished data). In addition, Savannah Sparrows are not evenly distributed within the Mountains and Valley region; thus, a better understanding of where they occur, as well as where they are most abundant, would allow for conservation efforts to be targeted toward specific geographic areas.

Savannah Sparrow conservation in Virginia may be best implemented through actions that benefit the broader grassland bird community. Some of these efforts are taking place through the Virginia Grassland Bird Initiative, a partnership that works to reverse declines of grassland birds on working lands in a 16-county area that straddles portions of the Piedmont, Blue Ridge Mountain region, and Shenandoah Valley. The Initiative provides technical assistance, educational workshops, and financial incentive programs to farmers and other landowners to carry out bird-friendly best management practices on their landscapes. Additional Virginia-specific resources provide habitat management guidelines that encompass Savannah Sparrow, among other grassland birds (Vuocolo et al. 2016).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Bailey, R. S., and C. B. Rucker (Editors) (2021). The second atlas of breeding birds in West Virginia. The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA, USA. 568 pp.

Hines, C. H., L. S. Duval, and B. D. Watts (2020). Winter distribution and migration ecology of the Ipswich Sparrow in the mid-Atlantic: Year 2020 report. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-20-06. William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. 8 pp.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Vuocolo, C., C. Sedgwick, S. Harding, F. Wolter, S. Capel, D. Pashley, and S. Heath (2016). Managing land in the Piedmont of Virginia for the benefit of birds and other wildlife: 3rd edition. Warrenton, VA, USA. 32 pp.

Wheelwright, N. T., and J. D. Rising (2020). Savannah Sparrow (Passerculus sandwichensis), Version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A F Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.savspa.01.