Introduction

The Sandwich Tern is an uncommon breeder and post-breeding visitor in coastal Virginia (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). It favors bare sand or sand-shell substrates and prefers to nest in densely packed groups, often interspersed with Royal Terns (Thalasseus maximus). Shortly after hatching, juveniles move into crèches alongside Royal Terns, where they continue to be attended by their parents (Shealer et al. 2020). Its distinctive black bill tipped with yellow makes it easily distinguishable from other terns in the region.

The Sandwich Tern was an uncommon nester in Virginia in the late 1800s, typically mixed in with Royal Tern colonies, and has never been widespread as a breeder (Weske et al. 1977). In Virginia, we have subspecies Thalasseus sandvicensis acuflavidus, also known as Cabot’s Tern.

Breeding Distribution

The Sandwich Tern was well-covered during the Second Atlas by the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey, a coastal census conducted by the Center for Conservation Biology in collaboration with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) and The Nature Conservancy. The survey identifies nesting locations of this and other species that breed in colonies. Because the Sandwich Tern only breeds within the survey area, there was no need to model its distribution. For information on where the species occurs in Virginia’s Coastal Plain, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

Given the breeding biology of the species, the Sandwich Tern is unlikely to have nested in blocks without confirmed breeding evidence (see Interpreting Species Accounts). Confirmation of breeding was based on records generated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey in 2018. Additional breeding confirmations were reported by Atlas volunteers in other years of the Second Atlas period.

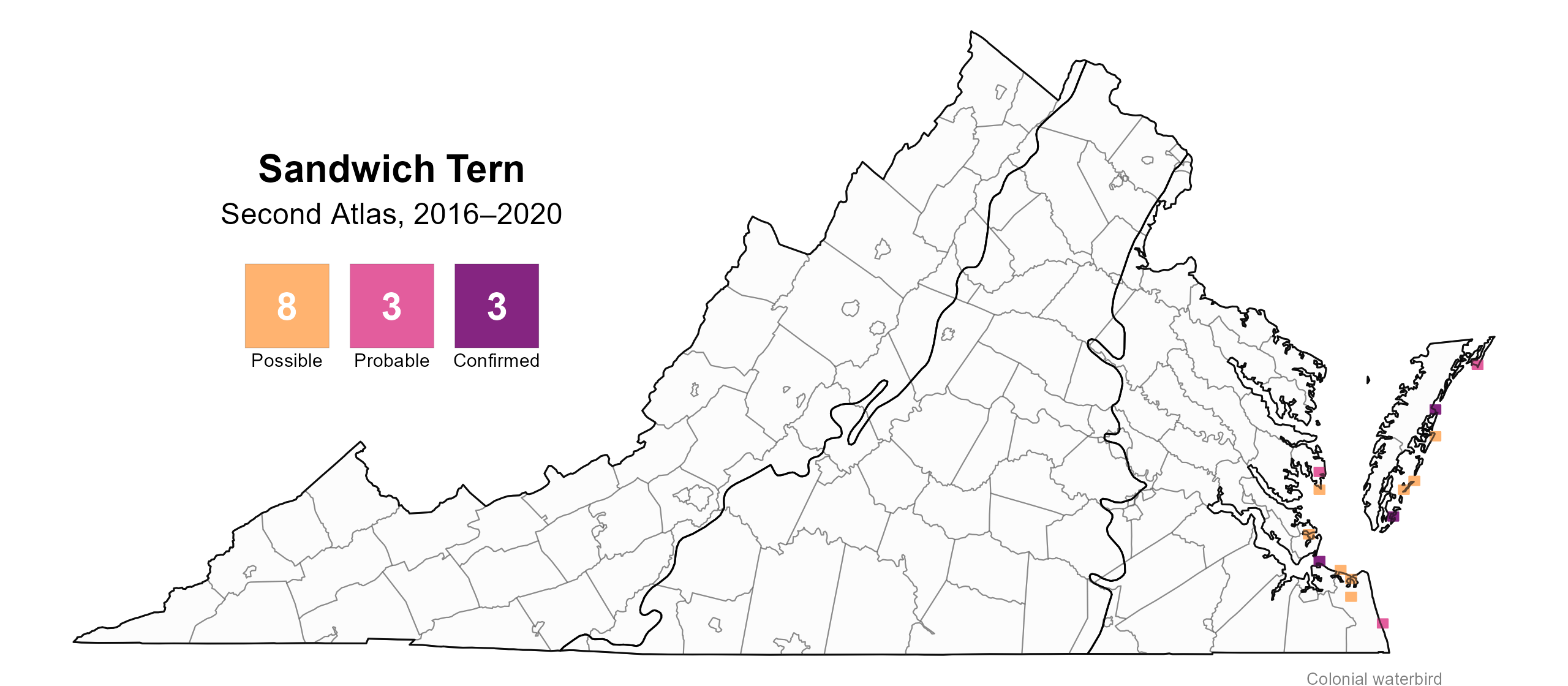

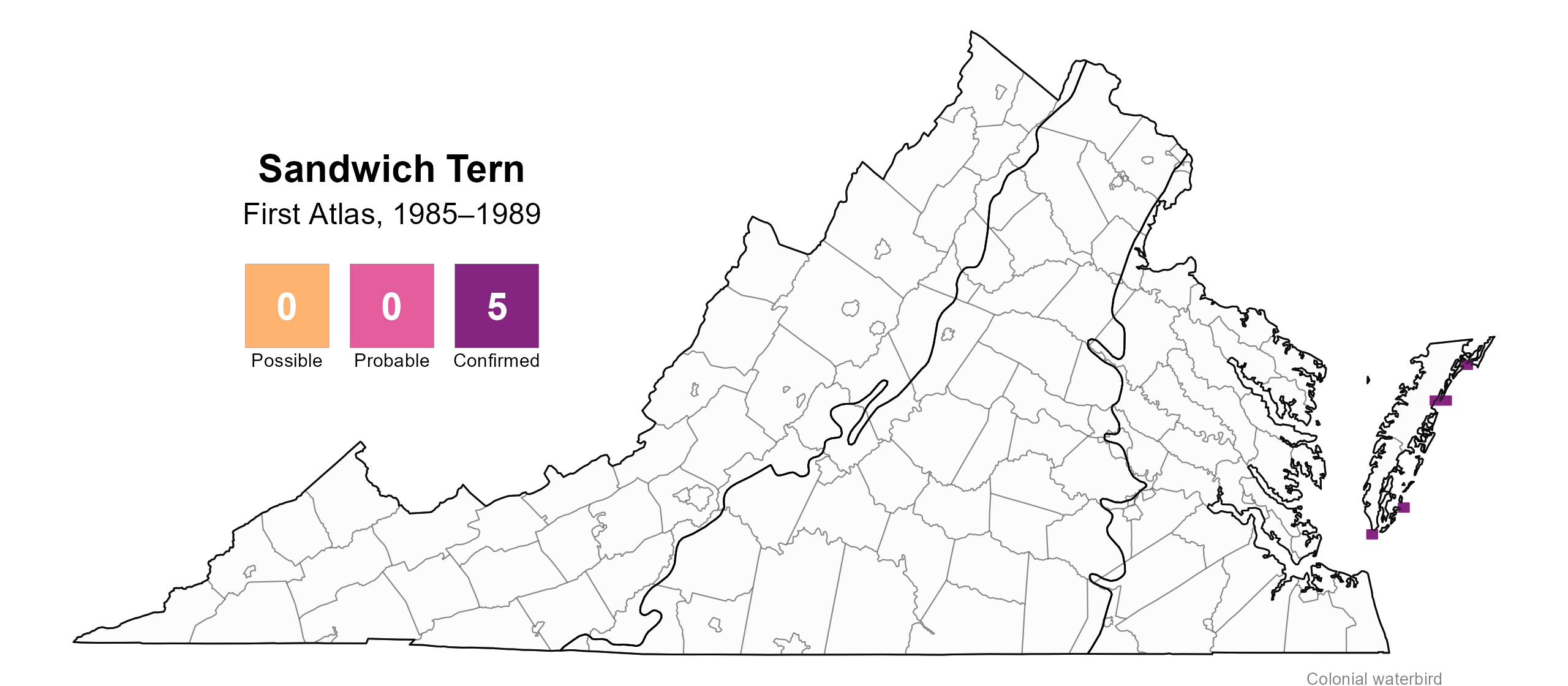

Sandwich Terns were confirmed breeders on Cobb Island in Northampton County and in the urban colony around the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (HRBT) in Hampton (Figure 1). During the First Atlas, Sandwich Terns were confirmed at a few additional barrier island sites but were not yet present at the HRBT (Figure 2).

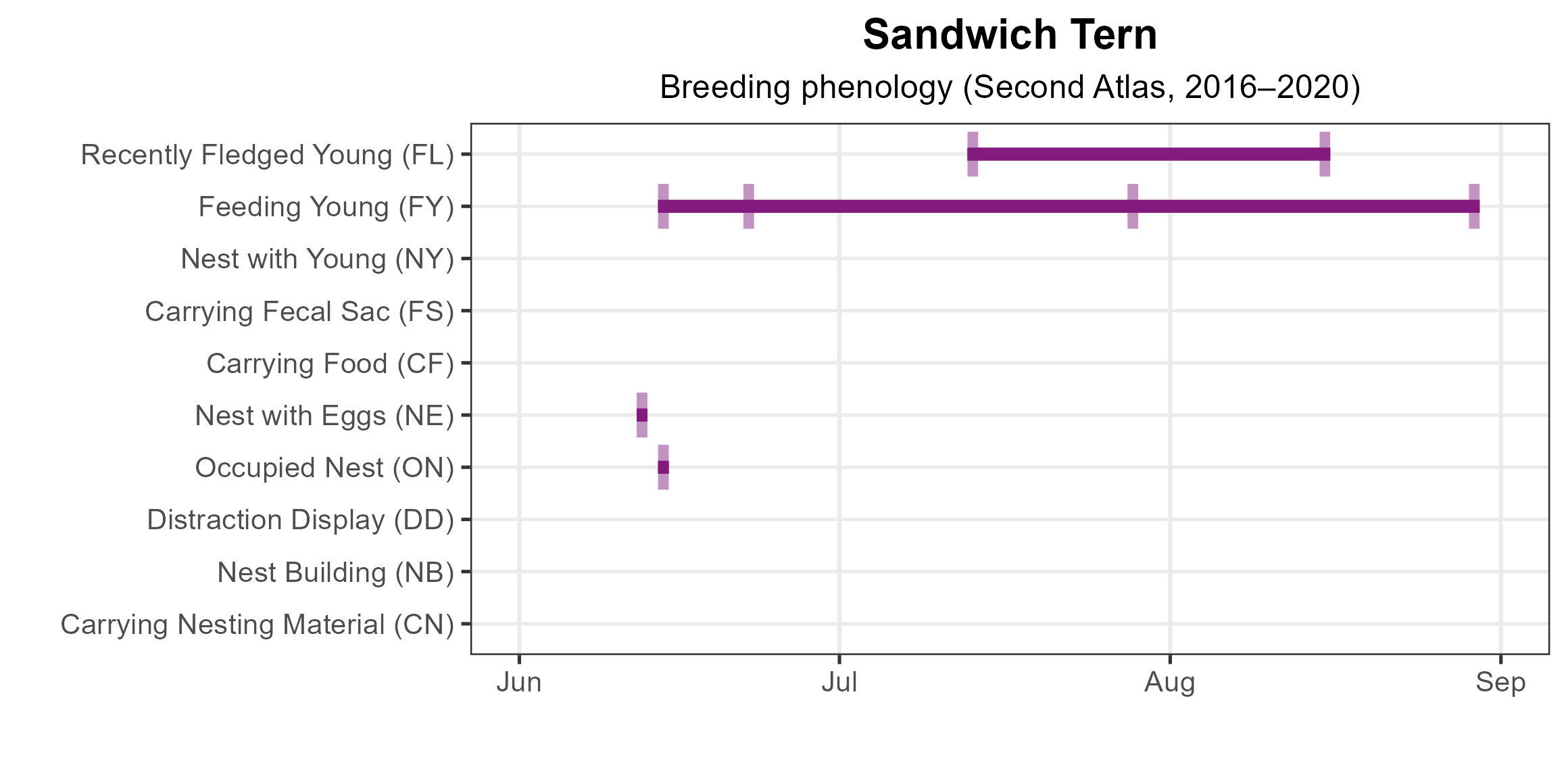

A limited number of observations precludes a complete picture of their breeding phenology. Sandwich Terns were on nests on June 12 (Figure 3). They were seen being fed by adults through August 29. Confirmations of recently fledged young, adults carrying food, and adults feeding young away from their few seaside colonies should be disregarded as a confirmation of breeding in that particular block; young can be dependent on parents well into autumn migration, far from their breeding colony (Shealer et al. 2020). For more general information on the breeding habits of the Sandwich Tern, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Sandwich Tern breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category. Nesting is unlikely outside of confirmed blocks.

Figure 2: Sandwich Tern breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Sandwich Tern phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Because the Sandwich Tern was not detected during Atlas point count surveys, an abundance model could not be developed. However, the distribution and size of Sandwich Tern colonies derived from the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey are displayed on the CCB Mapping Portal.

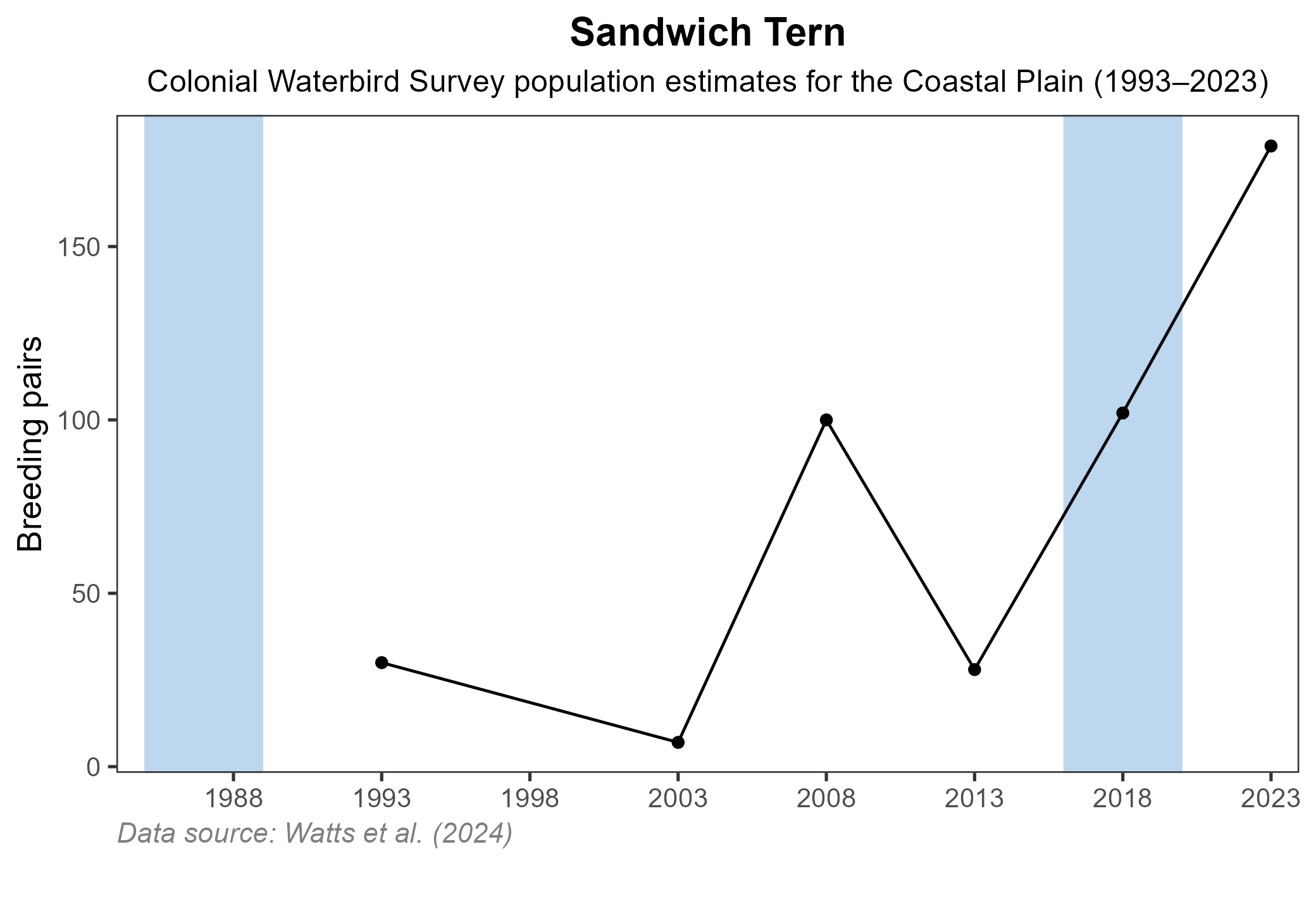

The Virginia Colonial Waterbird Surveys recorded a strong increase in the number of breeding pairs from 30 in 1993 to 179 in 2023, a six-fold increase, with some fluctuations in pair number in that period (Watts et al. 2024; Figure 4). This increase coincided with a similar increase in Royal Terns during the same period. However, it is difficult to assess their true population because birds move frequently among colonies and over state lines (Shealer et al. 2020). Overall, its breeding presence in Virginia is relatively new northern expansion.

Figure 4: Sandwich Tern population trend for Virginia’s Coastal Plain. This chart illustrates the number of breeding pairs as estimated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey (Watts et al. 2024). A data point is not included for 1998, as the Survey covered a smaller geographic area in that year. The vertical light blue bars represent the periods corresponding to the First Atlas (1985–1989) and Second Atlas (2016–2020).

Conservation

The Sandwich Tern is not classified as a species of concern in Virginia. Like most colonial-nesting birds, its populations are vulnerable to disturbance and loss of its limited number of nesting sites. Over 80% of Sandwich and Royal Tern nesting in Virginia occurred on South Island near the HRBT, a colony that was displaced when the Virginia Department of Transportation began a project to expand the tunnel. VDWR and partners were able to provide alternative habitat on the historic Fort Wool (also known as Rip Raps Island) and floating barges, which now provide replacement habitat for multiple nesting seabird species, including many Sandwich Terns (Sweeney et al. 2024). Based on the 2024 survey, they have continued to nest on Fort Wool since the effort began, and nesting activity on two of the three barges increased in 2024 (Sweeney et al. 2024). As with other beach-nesting species, Sandwich Terns can be protected by restricting disturbance and promoting public awareness around their nesting sites.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Shealer, D. S., J. S. Liechty, A. R. Pierce, P. Pyle, and M. A. Patten (2020). Sandwich Tern (Thalasseus Sanfvicensis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.santer1.01.

Sweeney, C., K. Hunt, J. Fraser, and S. Karpanty (2024). Assessing avian response to the relocation of Virginia’s largest seabird colony, 2024 annual report. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. B., and A. L Wilke (2019). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2018 breeding season. CCBTR-19-06. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. B., and A. L Wilke (2024). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2023 breeding season. CCBTR-24-12. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Weske, J. S., R. B. Clapp, and J. M. Sheppard (1977). Breeding records of Sandwich and Caspian Terns in Virginia and Maryland. The Raven 48:59–65.