Introduction

The tiny and highly nocturnal Northern Saw-whet Owl is a bird of northern North American woods, with the heart of its breeding distribution beginning in northern Pennsylvania and extending north and west though Canada. In Virginia, it is only known to breed in coniferous and semi-coniferous forests of the Mountains and Valleys region.

Saw-whet Owls are inconspicuous and secretive, requiring concentrated effort or incredible luck to observe outside of banding operations. To make matters more difficult, they are cavity nesters, meaning there is often no way to stumble upon them without seeing an adult provisioning young. Although natural cavities exist in their range, nearly all known breeding records in the southern Appalachians have been in artificial nest boxes.

The first known successful nesting record in the state was in 1995 in the Laurel Fork area of Highland County, in a nest box that had been placed for the federally endangered northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus) (Pagels and Baker 1997). Whether this means they do not typically use natural cavities, or merely that they are undetectable when they do so, is unclear.

Breeding Distribution

During the Second Breeding Bird Atlas, there were too few breeding observations to develop distribution models for the Northern Saw-whet Owl. Please see the Breeding Evidence sections for more information on breeding distribution in the state.

Breeding Evidence

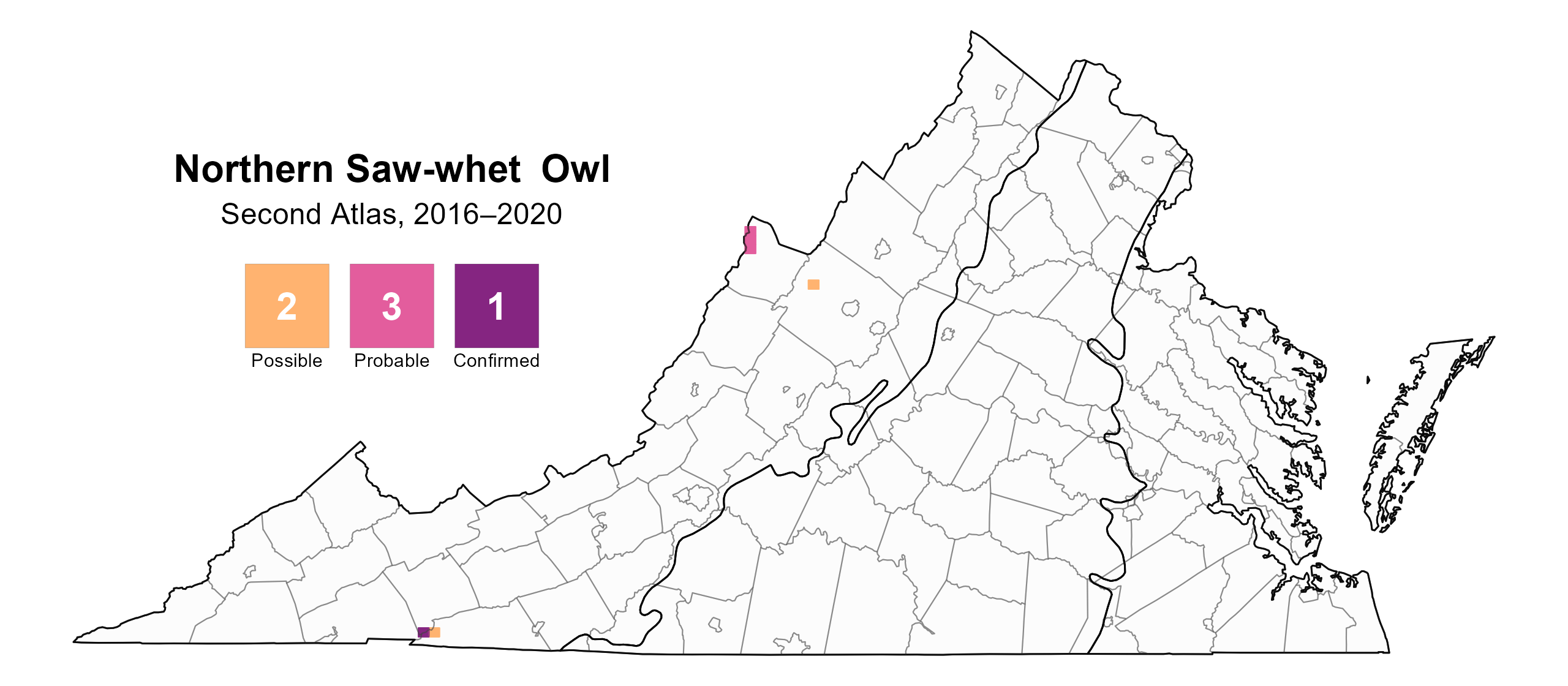

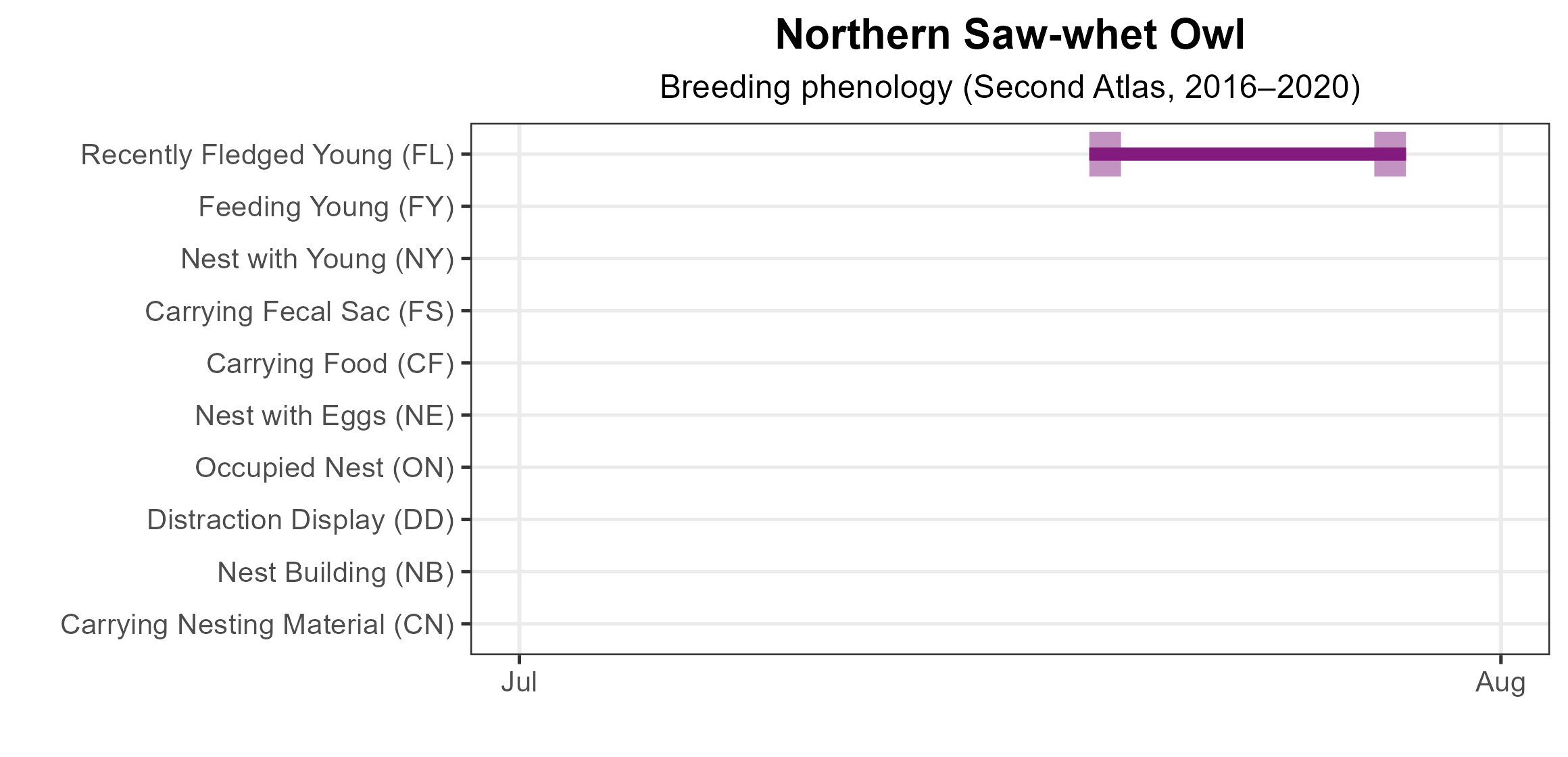

Northern Saw-whet Owls were confirmed breeders in only one block but were probable in three more blocks and possible in two (Figure 1). On July 19, 2020, a volunteer observed a juvenile Northern Saw-whet Owl on Whitetop Mountain in Grayson County. Nine days later, on July 28, 2020, a volunteer heard a juvenile Northern Saw-whet Owl calling from a location in Smyth County, just north of the original July 19 observation. Given that both observations were of recently fledged young near each other and not at fixed nest locations, it is likely that the two encounters stem from a single nest. In the same block, a territorial adult was observed just over the border in Washington County, also at Whitetop Mountain.

Northern Saw-whet Owls were found to be probable breeders in Highland County near Laurel Fork Wilderness Area, where adults birds were observed exhibiting territorial defense (June 12 and July 9, 2020) and agitated behaviors (July 2 and 9, 2020) (Figure 3). There were also possible breeders at Mt. Rogers (singing adult) and at Braley Pond in Augusta County (in appropriate habitat).

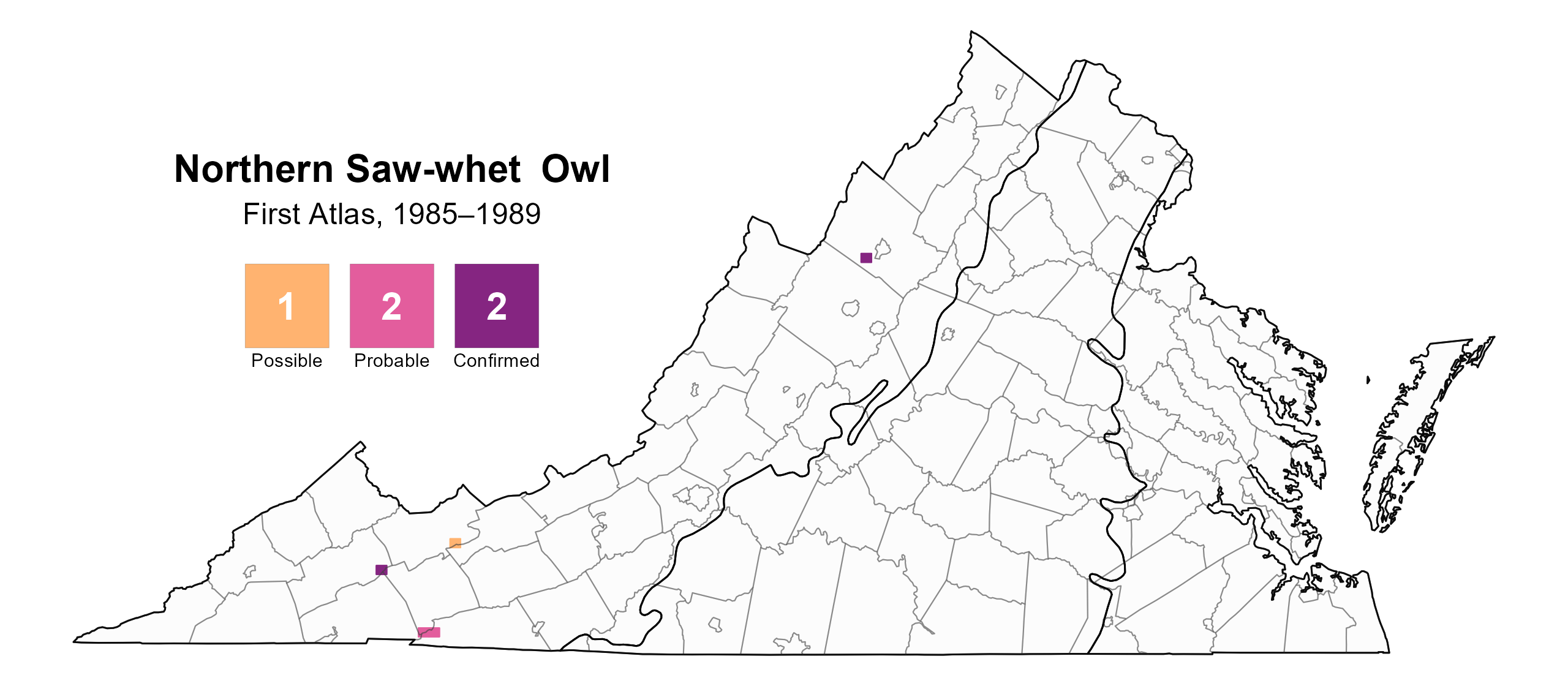

During the First Atlas, breeding was confirmed through five observations in two blocks. The confirmations were a nest with eggs at Clinch Mountain (Russell County), which apparently failed (Pagels and Baker 1997) and a confirmation near Harrisonburg (Rockingham County). Additional records were at high elevations in the Cumberland Plateau (Figure 2).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Northern Saw-whet Owl breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Northern Saw-whet Owl breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Northern Saw-whet Owl phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

The Northern Saw-whet Owl was not detected during Atlas point count surveys, so no abundance model could be developed. Additionally, it is not readily detected by the North American Breeding Bird Survey, which is unable to generate population trends for this species.

Conservation

Little is known about the Northern Saw-whet Owl’s population in Virginia, including its size and trend. Without this information, the species cannot be evaluated for inclusion as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need. Thus, the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan classifies it as an Assessment Priority Species, highlighting the importance of learning more about its distribution and population in the Commonwealth (VDWR 2025).

It is likely that Northern Saw-whet Owls occur more extensively than indicated by either Atlas and other survey efforts; thorough surveys will help shed light on this secretive, little bird (Dolby and Mellinger 2006). In fact, prior to the First Atlas, there were summer observations that strongly suggested breeding at Bennett Springs near Roanoke (Engleby 1941), at Mount Rogers (Shelton 1976), in Grayson Highlands State Park (Simpson 1976), at Whitetop Mountain (Clapp 1997), in Highland County (Larner 1985), and at Beartown Mountain (Peake 1987).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Clapp, R. B. (1997). Egg dates for Virginia birds. Virginia Avifauna No. 6. Virginia Society of Ornithology, Lynchburg, VA, USA. 123 pp.

Dolby, A. and C. Mellinger (2006). The Virginia Society of Ornithology 2006 foray: a focus on the Northern Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius acadicus). The Raven 77:23–26.

Engleby, T. L. (1941). Saw-whet Owls at Roanoke. The Raven 12:67.

Larner, Y. (1985). The Highland County Foray of June 1985. The Raven 56:25–37.

Pagels, J. F. and J. R. Baker (1997). Breeding records and nesting diet of the Northern Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius acadicus) in Virginia. The Raven 68:89–92.

Peake, R. H. (1987). The results of the 1986 Tazewell County (Virginia) foray. The Raven 58:1–17.

Rasmussen, J. L., S. G. Sealy, and R. J. Cannings (2020). Northern Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius acadicus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.nswowl.01.

Shelton, P. C. (1976). Observations of northern birds on Mt. Rogers. The Raven 53:51–53.

Simpson, M. B. (1976). Breeding season record of the Saw-whet Owl from Grayson Highlands State Park, Virginia. The Raven 47:56–57.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.