Introduction

Ungainly on land and in flight, the Double-crested Cormorant is best suited to water. It swims gracefully, snakelike neck the only part visible above the surface between dives. Once it hauls out, it must hang its wings to dry in the sun. In breeding plumage, adults grow their namesake “double crest,” a pair of white head tufts that frame their sea-green eyes and orange facial skin. While cormorants are known to primarily select natural breeding sites on coastal and freshwater islands and marshes, they also nest on artificial structures such as electrical transmission towers, derelict barges, and duck blinds in open water, which likely provide insulation from mammalian predators (Watts 1996).

The first breeding record in Virginia was in 1978 on the James River in a mixed-species heronry, marking the species’ first known nesting in the Chesapeake Bay and Mid-Atlantic (Blem et al. 1980). It was unclear whether this population represented the P. a. floridanus subspecies from Florida or P. a. auritus, which nests north and inland. By the time of the First Atlas, the James River population was rapidly expanding, reaching the Eastern Shore by 1995 (Watts 1996).

Breeding Distribution

Within the Coastal Plain, the Double-crested Cormorant was well-covered during the Second Atlas by the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey, a coastal census conducted by the Center for Conservation Biology in collaboration with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) and The Nature Conservancy. The survey identifies nesting locations of this and other species that breed in colonies. Therefore, there was no need to model its distribution within that region. For information on where the species occurs in Virginia’s Coastal Plain, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

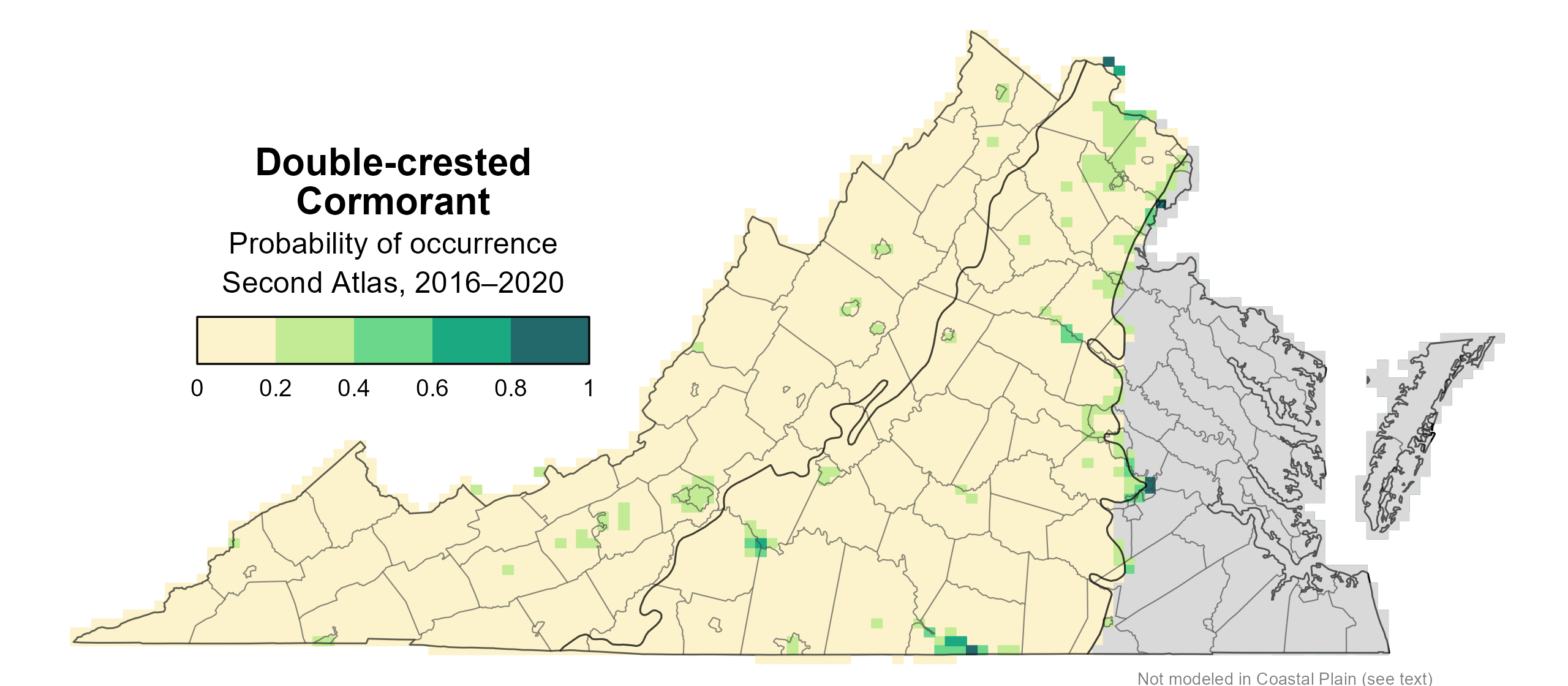

Outside of the Coastal Plain region, during the breeding season, Double-crested Cormorants occur along all major coastal waterways as well as large inland reservoirs such as Kerr Lake in Mecklenburg County and Smith Mountain Lake in Franklin, Bedford, and Pittsylvania Counties (Figure 1). Similar to other species whose distribution is tied to water and riparian habitats, their occupancy is predicted based on negative effects. Double-crested Cormorants were less likely to occur in blocks with a high proportion of forest, agricultural land, or developed land cover or in blocks with many forest patches. Occupancy was higher in blocks with a greater number of habitat types, likely capturing the presence of aquatic habitats.

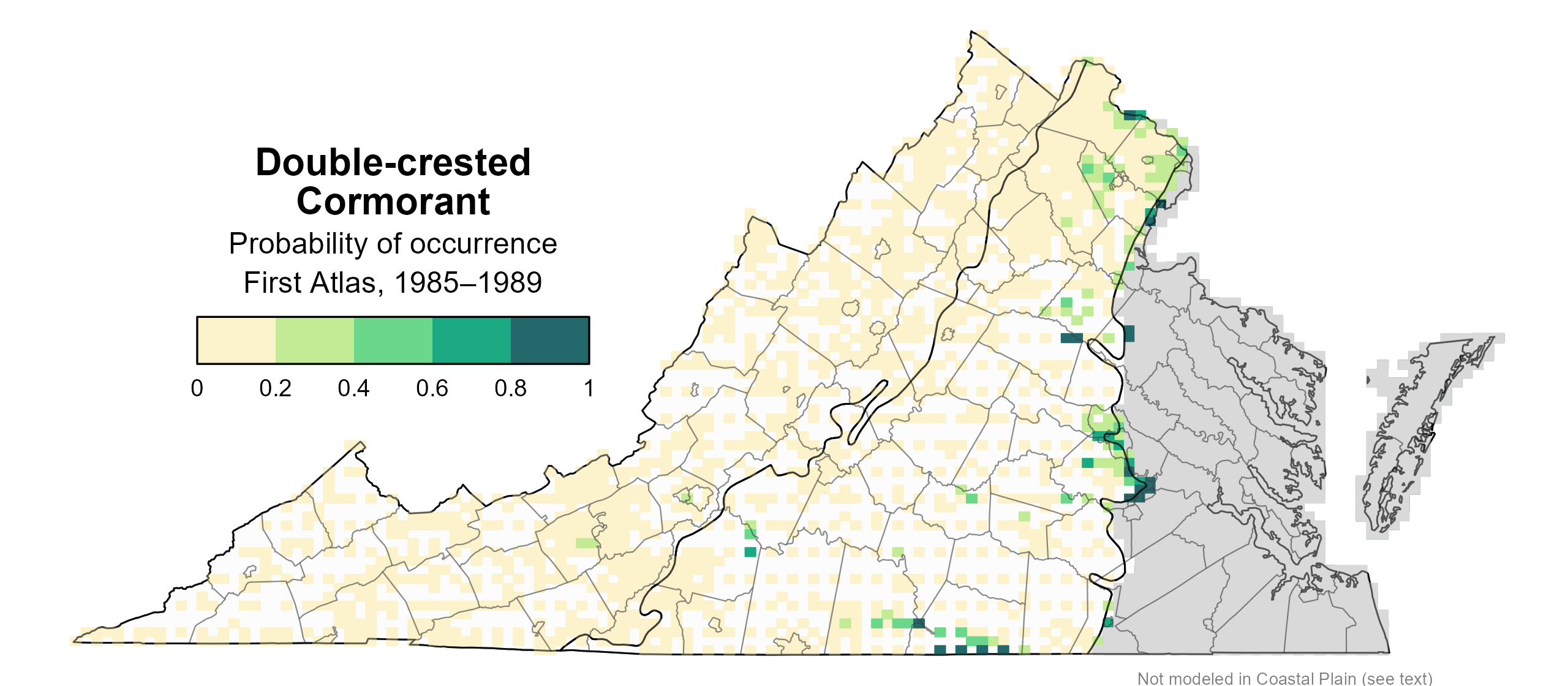

Between Atlases, the Double-crested Cormorant’s probability of occurrence outside the Coastal Plain region remained the same (Figures 1 to 3).

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Double-crested Cormorant breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 1: Double-crested Cormorant breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Double-crested Cormorant change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

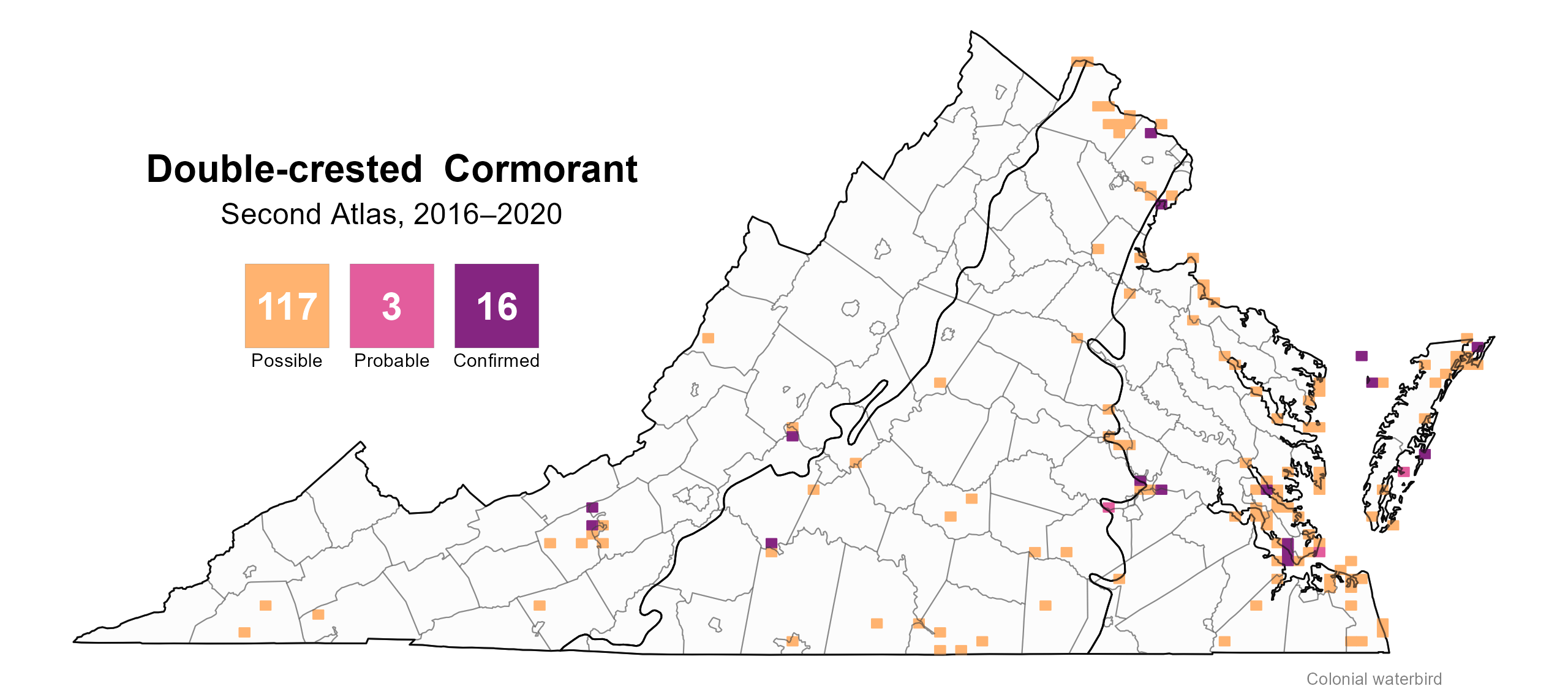

Given that the locations of nesting colonies were documented by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey in 2018, Double-crested Cormorants in the Coastal Plain are unlikely to have nested in blocks without confirmed breeding evidence. There were additional breeding confirmations reported by Atlas volunteers in other years of the Second Atlas period. Outside of the Coastal Plain, where there is no systematic survey to identify nesting colonies, the nesting status of the species in blocks without confirmed breeding evidence is less clear.

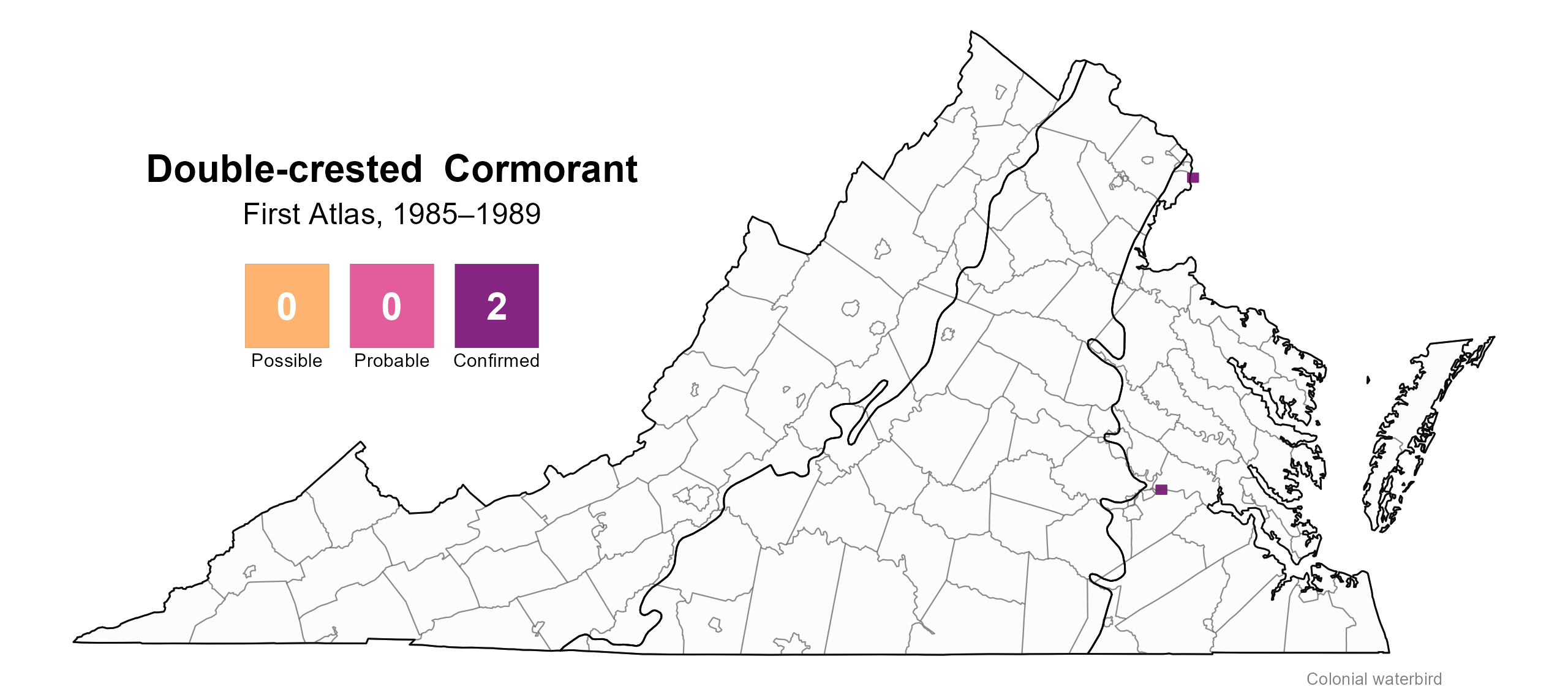

Double-crested Cormorants were confirmed in 16 blocks in 10 counties and three cities (Figure 4). Most strikingly, colonies were recorded in all three physiographic regions, a major expansion from the First Atlas, which documented only two blocks with confirmed breeders in the Coastal Plain (Figure 5). Most colonies were formed or discovered after the First Atlas.

In the Mountains and Valleys region, cormorants nested along the New River in Pulaski County and the city of Radford, as well as on the upper reaches of the James River in Amherst County. In the Piedmont region, colonies were documented both in Northern Virginia, along the Potomac River at Great Falls in Fairfax County, and in the southern Piedmont region at Smith Mountain Lake in Bedford County. In the Coastal Plain region, breeding sites included several locations along the James River, such as James River Park in Richmond, Dutch Gap Conservation Area in Chesterfield County, Jordan Point Marina in Prince George County, James City County, and the James River Bridge in Newport News. Additional colonies were located on the York River at New Quarter Park and the Cheatham Annex naval base in York County and on the Eastern Shore near Tangier Island, in Chincoteague Bay, and at Quinby Inlet.

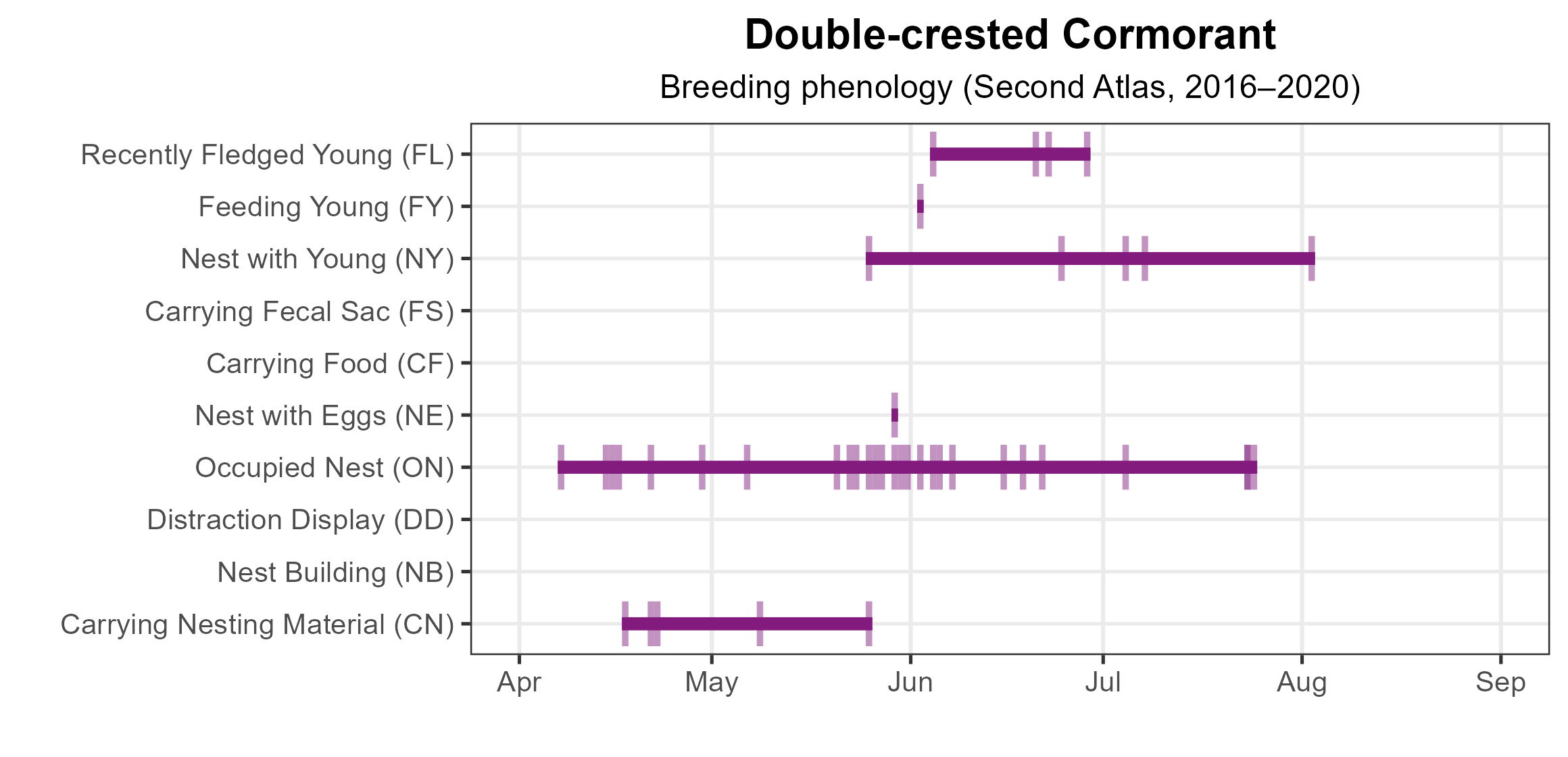

Large nesting colonies can be conspicuous when present, both due to their size and the unmistakable stench of guano and fish. However, there are also small colonies (<20 pairs) that are much more inconspicuous; thus, given the small number of colonies and their often-inaccessible locations, breeding phenology is only partially documented. Nests were documented as occupied as early as April 7, with adults carrying nesting material observed between April 17 and May 25. Only one observation documented nests with eggs on May 29. Young were in the nest from May 25 through August 2 (Figure 6). As a colonial species, cormorants are underrepresented in Atlas data because only the highest breeding code is typically submitted per site, and multiple nests within a colony are not individually recorded. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Double-crested Cormorant, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 5: Double-crested Cormorant breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020) The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Double-crested Cormorant breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Double-crested Cormorant phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Double-crested Cormorants had too few detections during the Atlas point count surveys to develop an abundance model. However, the distribution and size of Double-crested Cormorant colonies derived from the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey are displayed on the CCB Mapping Portal.

Cormorant populations have changed dramatically in recent history. Cormorant populations declined sharply in the late 1800s due to human persecution, began recovering gradually through the 20th century, and then stagnated during the era of DDT and other persistent pesticides starting in the 1940s (Hatch 1995). Rapid recovery began in the late 1970s and early 1980s, leading to population expansions, including into Virginia.

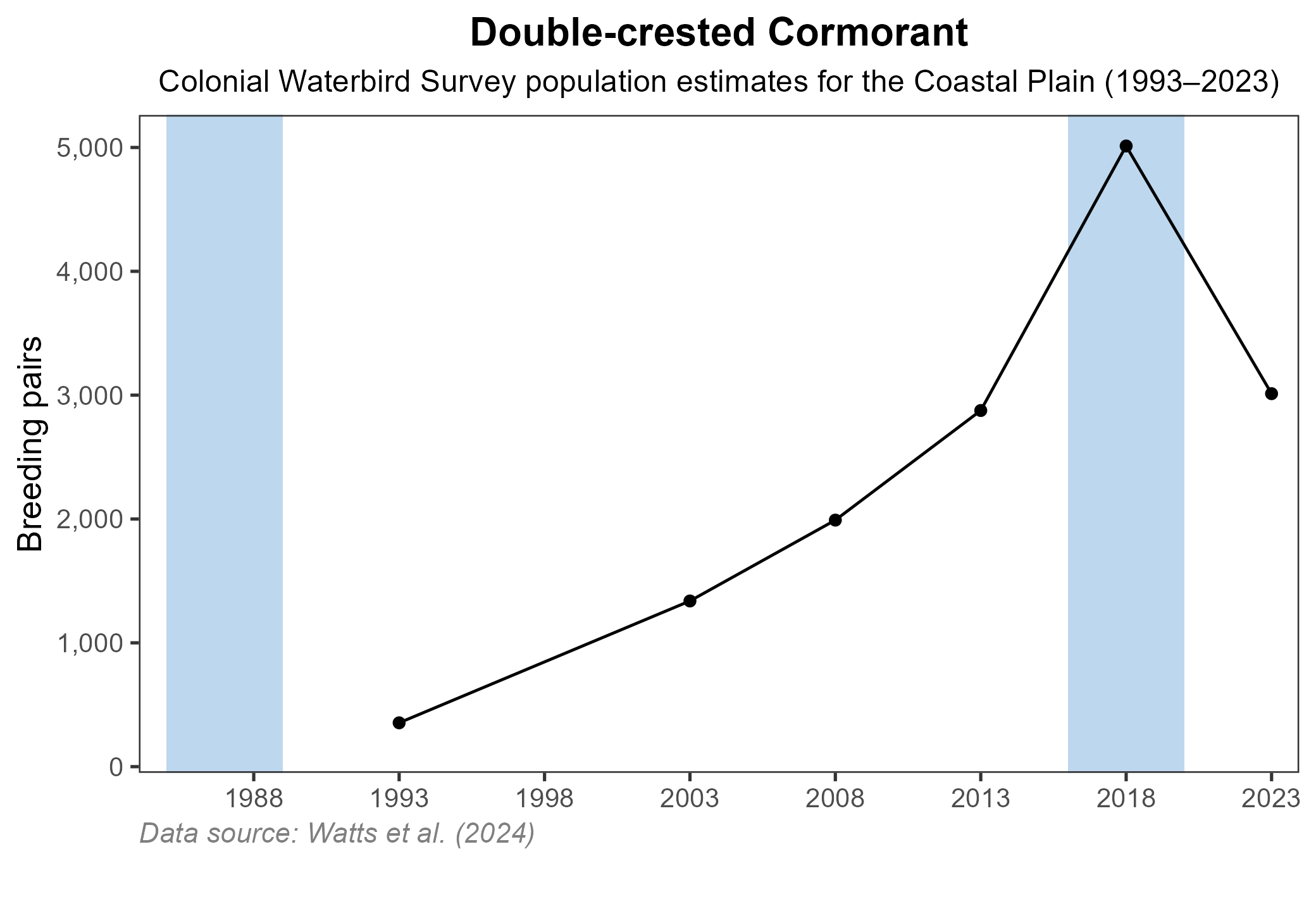

More recently, the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey data indicate explosive growth since establishment. From six pairs in 1978, the population grew to 354 pairs by 1993 and peaked at 5,012 pairs in 2018. By 2023, however, the number dropped to 3,012 pairs, a 40% decline due to habitat loss and sea-level rise at Shanks Island in the northern Chesapeake Bay, which historically hosted over 90% of Virginia’s breeding population (Watts et al. 2024; Watts 2024). The formation of new colonies has not been enough to offset this loss.

Figure 7: Double-crested Cormorant population trend for Virginia’s Coastal Plain. This chart illustrates the number of breeding pairs as estimated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey (Watts et al. 2024). A data point is not included for 1998, as the Survey covered a smaller geographic area in that year. The vertical light blue bars represent the periods corresponding to the First Atlas (1985–1989) and Second Atlas (2016–2020).

Conservation

This species is much maligned and faces threats from human opinion. Across their range, cormorants are persecuted for real or perceived impacts on fisheries, island vegetation, and other bird species. Depredation permits allow culling and nest destruction in some states (Dorr et al. 2021). In Virginia, only a small colony on a ship in the James River ghost fleet has been intentionally removed (Watts 2022).

The initial population found breeding in Virginia was noted to be at a site on the James River that was highly polluted with the pesticide Kepone, where fishing was banned at the time (Blem et al. 1980). As piscivores, cormorants are exposed extensively to waterborne contaminants including PCBs, which remain elevated in parts of the James River (Hines-Acosta 2024).

Sea-level rise is an increasing threat to all colonial waterbirds. The erosion of Shanks Island has already had major demographic consequences. These impacts continue today, as the colony at Shanks Island failed in August 2025, with almost 500 abandoned nest structures and a number of scattered broken eggs (Ruth Boetcher, personal communication). However, the Double-crested Cormorant continues to expand inland and appears to have a stable future in the region. Whether their growing presence will be tolerated by all stakeholders remains uncertain.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Blem, C. R., W. H. Gutzke, and C. Filemyr (1980). First breeding record of the Double-crested Cormorant in Virginia. Wilson Bulletin 92:127–128.

Dorr, B. S., J. J. Hatch, and D. V. Weseloh (2021). Double-crested Cormorant (Nannopterum auritum), version 1.1. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.doccor.01.1.

Hatch, J. J. (1995). Changing populations of Double-crested Cormorants. Colonial Waterbirds 18:8–24. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1521520?origin=crossref.

Hines-Acosta, L. (2024). Virginia report details PCB levels in James River watershed. Bay Journal.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Watts, B. (2022). Virginia cormorants continue historic rise. Center for Conservation Biology. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. (2024). Cormorants add colonies but decline in Coastal Virginia. Center for Conservation Biology. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D. (1996). Population expansion by Double-crested Cormorants in Virginia. The Raven 67:75–78.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. Boettcher, and A. L. Wilke (2024). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2023 breeding season. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University, CCBTR-24-12. Williamsburg, VA, USA.