Introduction

Our country’s national symbol has made one of the most sweeping comebacks of any species in history. In Virginia, and throughout the Bald Eagle’s range, the chemical pesticide known as DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) had devastating impacts on populations (Buehler 2022). In 1977, a few years after the Endangered Species Act was passed, Virginia supported under 50 breeding pairs of Bald Eagles (Watts 2005). A federal ban on DDT in 1972 coupled with intensive management and nest-site protection efforts by federal and state wildlife agencies supported by the Endangered Species Act initiated a population resurgence that continues to this day (VDWR and CCB 2012). In 2007, the Bald Eagle was removed from the federal list of endangered and threatened species, and Virginia removed it from the state list in 2013 (USFWS 2007; VDWR and CCB 2012). Today, there are more than 2,000 pairs breeding throughout the state (Jeffrey Cooper, personal communication).

Breeding Distribution

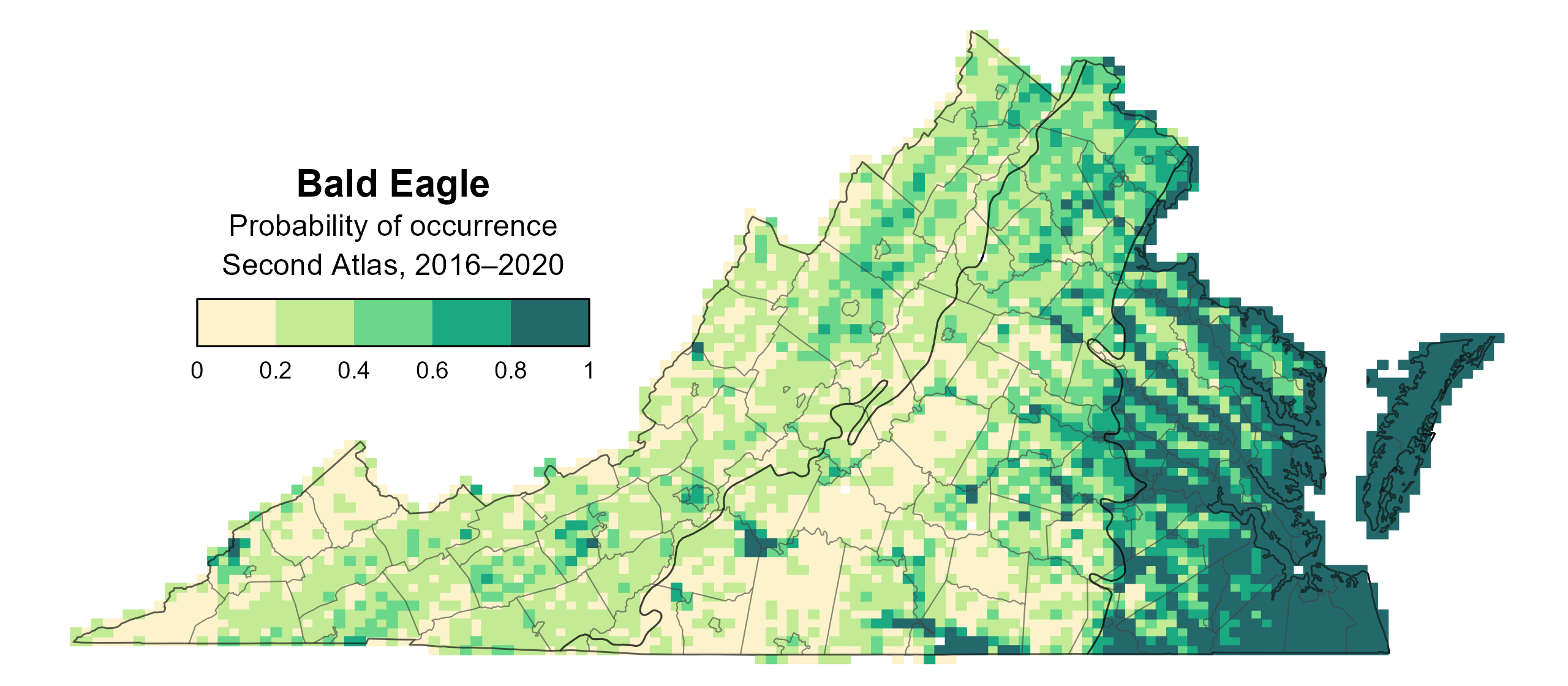

Although Bald Eagles occur throughout the state, they are more likely to occur in the eastern one-third of the Coastal Plain where riparian systems, estuaries, and coastlines provide excellent foraging habitat for fish (Figure 1). However, Bald Eagles have expanded and are also found in the Piedmont and Mountains and Valleys regions.

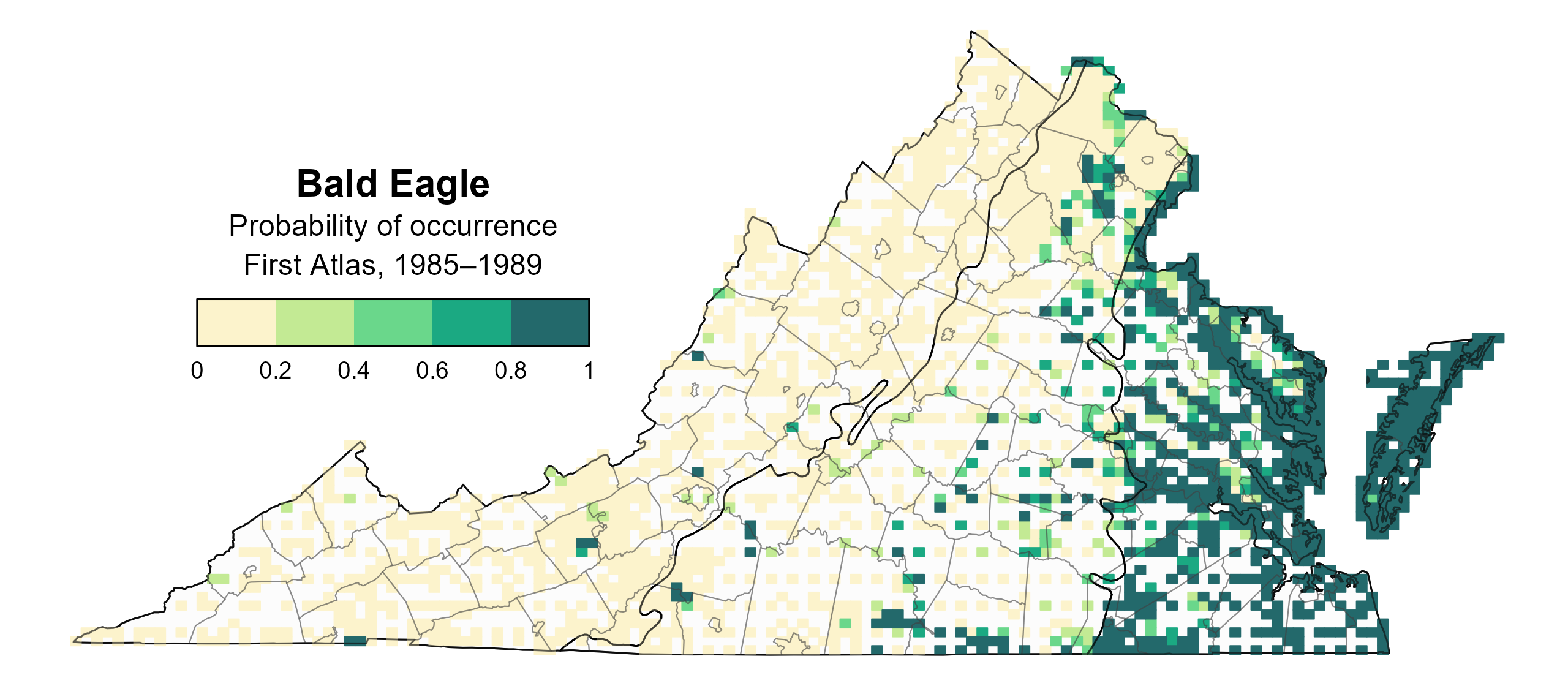

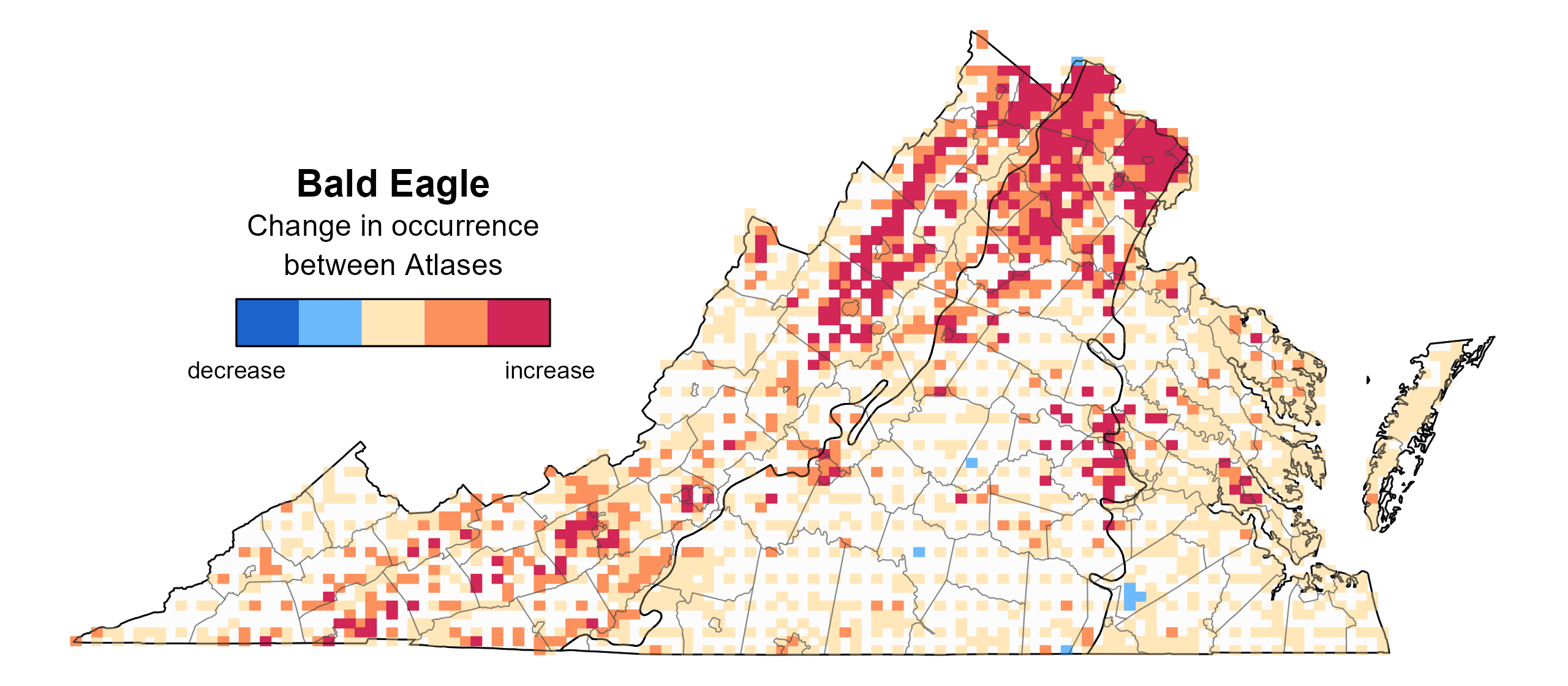

Consistent with overall population growth, the Bald Eagle’s likelihood of occurrence increased substantially from the First to Second Atlas (Figures 1 and 2). However, statistical models perform poorly in terms of predicting change that is driven by unmeasurable external forces, which in this case was the removal of DDT from the environment, coupled with natural immigration from recovered populations in other areas and increased chick production within the Chesapeake Bay region. Consequently, the change model represented in Figure 3 underestimates the explosive growth in Bald Eagle populations between Atlas periods. For instance, Figure 3 shows that Bald Eagle populations remained mostly constant across the Coastal Plain, when their likelihood of occurring on the landscape increased greatly during that period.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Bald Eagle breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Bald Eagle breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Bald Eagle change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

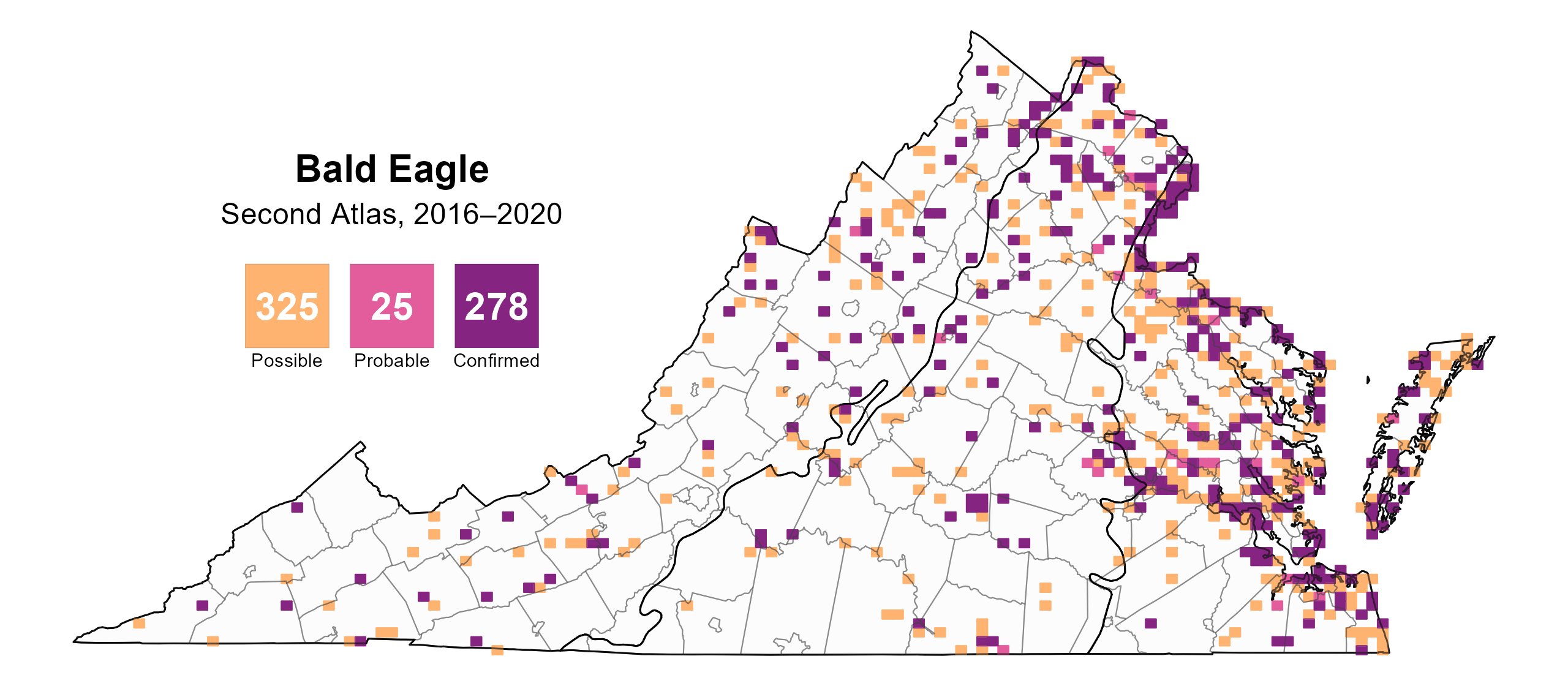

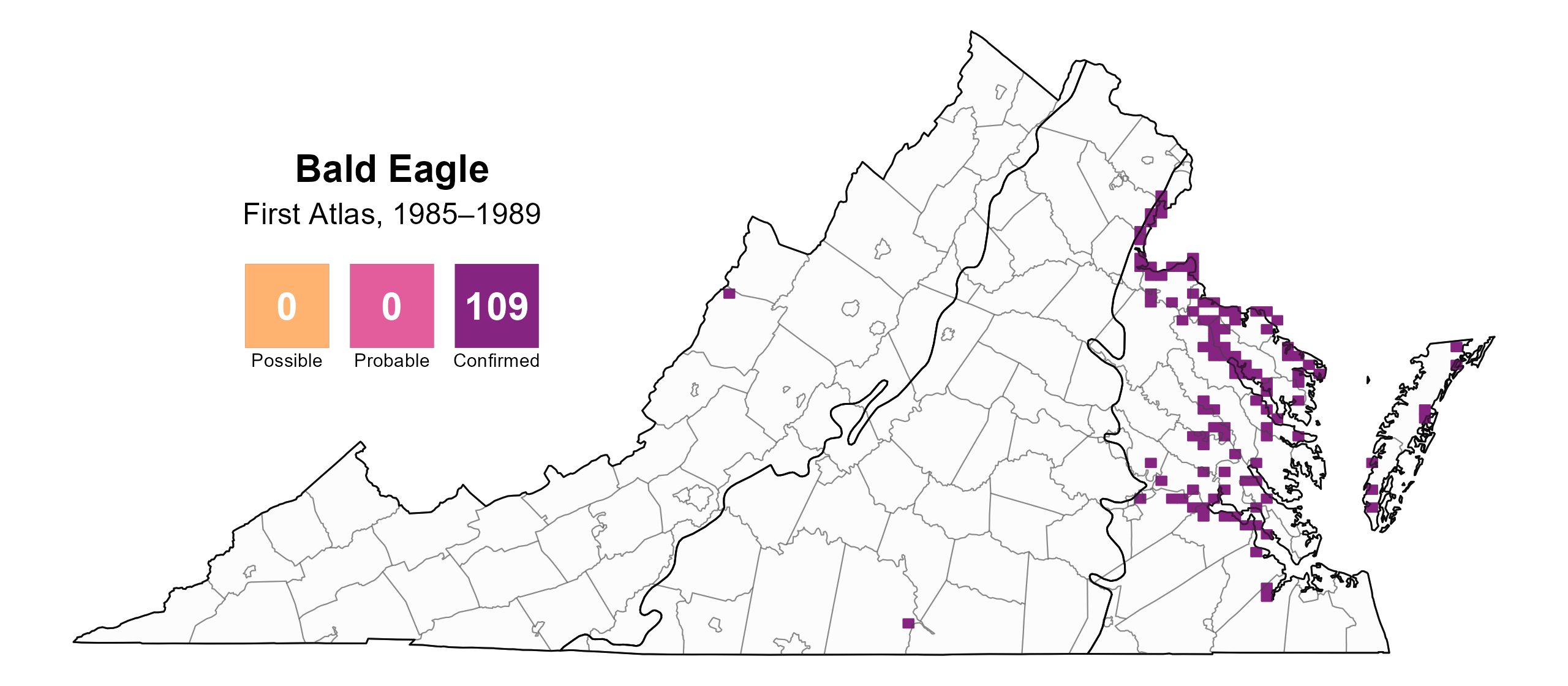

Bald Eagles were confirmed breeders in 278 blocks and 84 counties and probable breeders in one additional county (Figure 4). However, this value may be an underestimation, as Bald Eagles likely occur in most counties in the state (Jeffrey Cooper, personal communication). During the First Atlas, confirmed breeders were mainly recorded in the Coastal Plain region as they had not yet experienced population restoration and expansion (Figure 5).

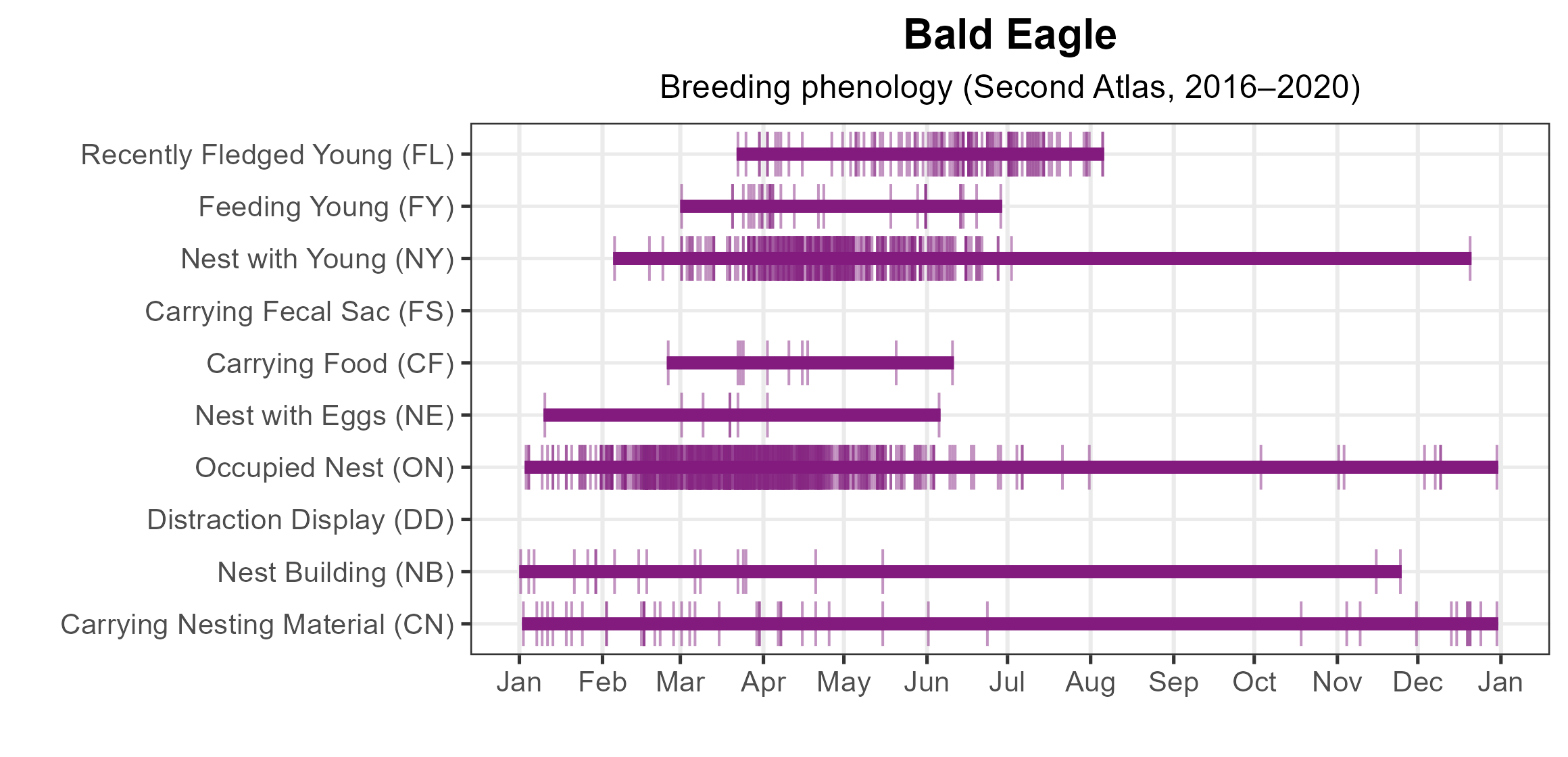

Breeding was confirmed in early January when nest building (January 1), adults carrying nesting material (January 2), and occupied nests (January 3) were recorded (Figure 6). Most breeding confirmations were based on observations of occupied nests, nests with young, and recently fledged young. More specifically, during the Second Breeding Bird Atlas, volunteers documented occupied nests during almost every month of the year, while nests with young were observed as early as February and as late as December. For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Bald Eagle breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Bald Eagle breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Bald Eagle phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

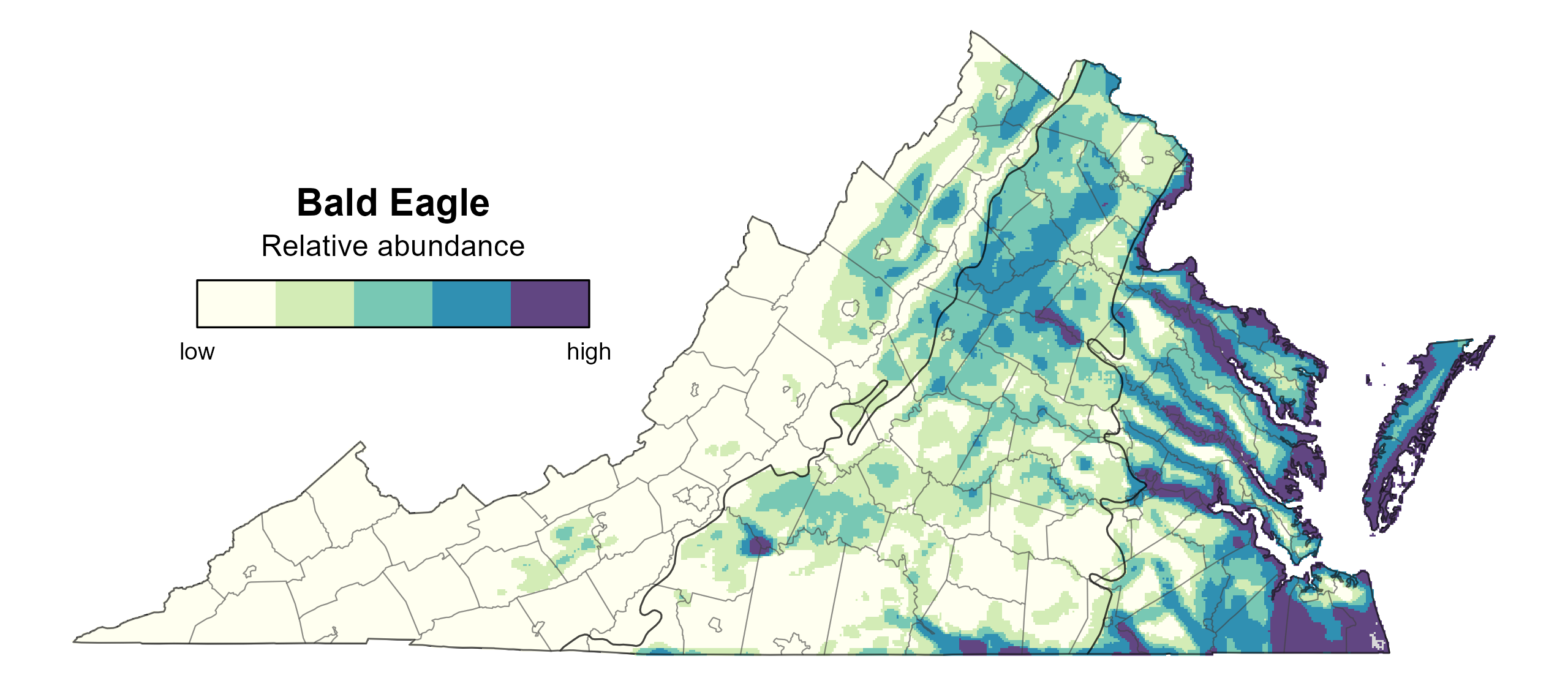

Bald Eagle relative abundance was estimated to be highest along the Potomac, Rappahannock, and James Rivers; on the Eastern Shore; and in the most southeastern part of the Coastal Plain region (Figure 7).

The total estimated Bald Eagle population in the state is approximately 14,000 detectable individuals (with a range between 4,000 and 46,000). The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) does not produce a credible trend for the Bald Eagle at state and regional levels; however, in Virginia, the population has increased at a rate of 8% annually since the 1970s and is now starting to level off (Bryan Watts, personal communication).

Figure 7: Bald Eagle relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Conservation

With Bald Eagle populations now reaching the carrying capacity of Virginia’s habitat, conservation efforts have shifted from growing the number of eagles to managing risks, such as eagles colliding with aircrafts, communications towers, and wind turbines. This effort includes ensuring that new structures are sited in places that minimize collision risk to Bald Eagles and other migratory wildlife.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Buehler, D. A. 2022. Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), version 2.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald and S. G. Mlodinow, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.baleag.02.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) (2007). Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; removing the Bald Eagle in the lower 48 states from the list of endangered and threatened wildlife. Federal Register 72(130):37346–37372.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources and the Center for Conservation Biology (VDWR and CCB) (2012). Management of Bald Eagle nests, concentration areas, and communal roosts in Virginia: a guide for landowners. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D. (2005). Virginia Bald Eagle conservation plan. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-05-06. College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. 52 pp.