Introduction

The buzzy, easy-to-recognize song of the Black-throated Green Warbler carries from high in the treetops. Two subspecies occur in Virginia, each occupying a distinct region. The nominate subspecies, Setophaga virens virens, breeds in coniferous and mixed forests along the Appalachian Mountains. S. v. waynei, hereafter Wayne’s Warbler, is a genetically distinct subspecies with a smaller bill (Carpenter et al. 2022). Wayne’s Warbler is restricted to coastal swamps from South Carolina to southeastern Virginia, where it is closely associated with mature portions of swamps and adjacent forested habitats (Morse et al. 2024).

Breeding Distribution

While a common migrant throughout Virginia during spring and fall (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007), Black-throated Green Warblers virtually disappear from the Coastal Plain and Piedmont regions during the breeding season. This section focuses only on the nominate subspecies in the Mountains and Valleys region, where sufficient data were available to produce models, whereas data for Wayne’s Warbler in the Coastal Plain were insufficient. For breeding records outside of the modeled region, see the Breeding Evidence section.

Black-throated Green Warblers are most likely to occur around Mount Rogers in Grayson, Smyth, and Washington Counties and along the West Virginia line in Highland, Augusta, and Rockingham Counties, as well as along other major ridgelines in the Mountains and Valleys region (Figure 1). The Black-throated Green Warbler prefers higher elevations, which was the key predictor of its presence. The warbler also has a positive association with evergreen shrubs such as mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia) and rhododendron (Rhododendron spp.) and a slightly positive association with larger forest patches.

The Black-throated Green Warbler’s probability of occurrence in the Second Atlas was largely similar that in the First Atlas (Figure 2) with slight increases in several small areas in the Mountains and Valleys region (Figure 3).

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Black-throated Green Warbler breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray lie outside the core range of the species and were not modeled.

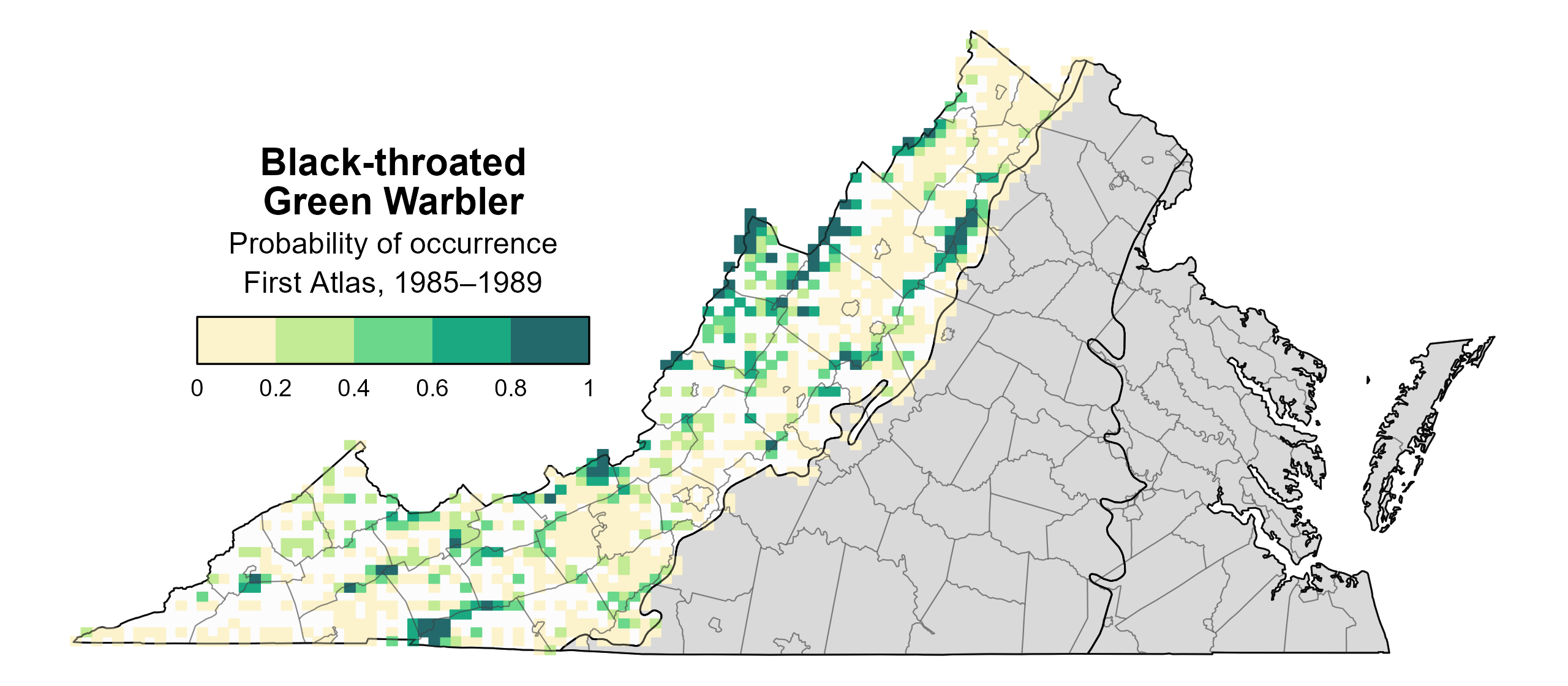

Figure 2: Black-throated Green Warbler breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Black-throated Green Warbler change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas so were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

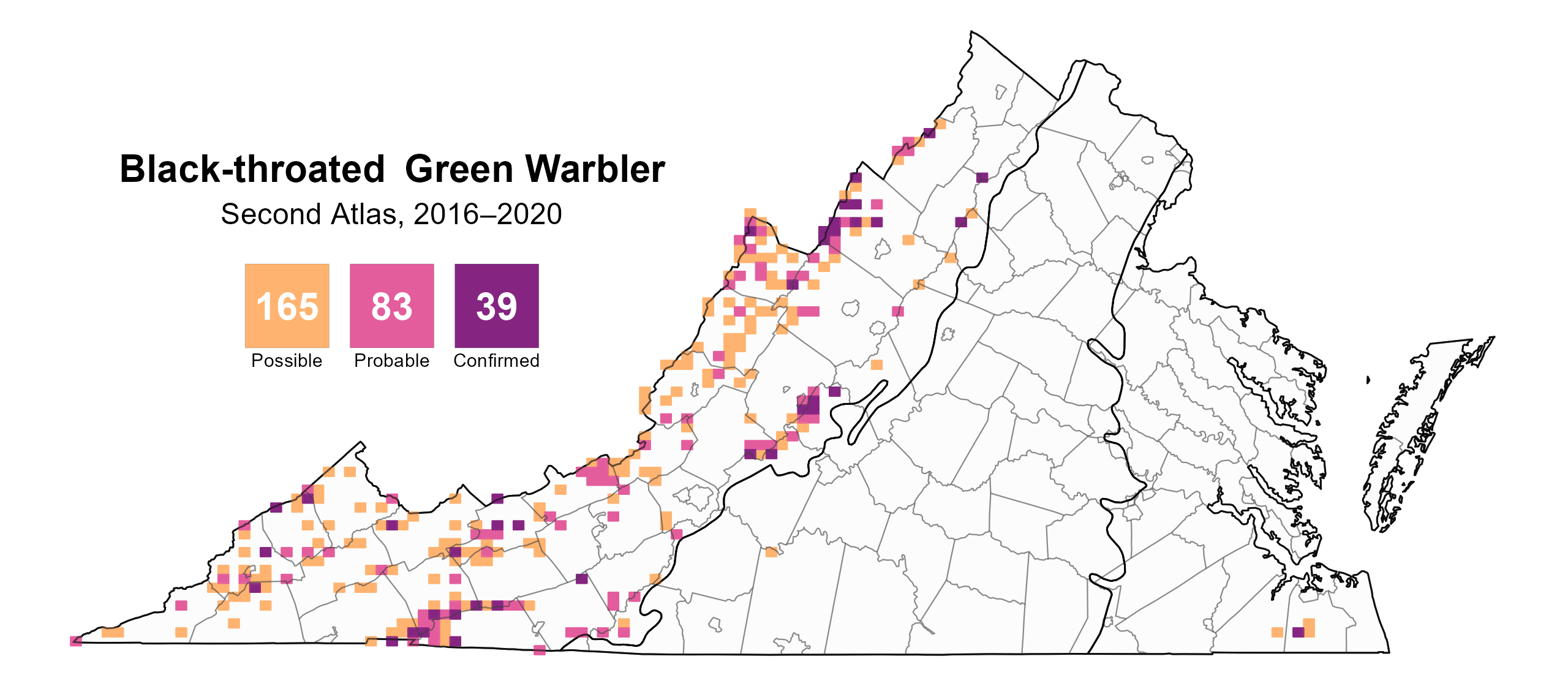

Black-throated Green Warblers were confirmed breeders in 39 blocks across 21 counties and probable breeders in an additional 12 counties in the Mountains and Valleys region. Two records of a singing male at Smith Mountain Cooperative Wildlife Management Area in Pittsylvania County may have been of a late migrant.

Wayne’s Warbler was only confirmed as a breeder in one block in the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge, but it was present as a possible breeder in three additional blocks within or adjacent to the Refuge in the cities of Chesapeake and Suffolk. However, a targeted survey effort in 2024 confirmed breeding in patches throughout the Great Dismal Swamp including the forest along the outflow of the Northwest River. Ongoing efforts are aimed at better understanding the breeding distribution of this subspecies outside of the Dismal Swamp (Hines et al. 2024).

Most confirmations in the Mountains and Valleys were of adults carrying food or recently fledged young. While some nests are built below six feet (two meters), most nests are higher in the canopy and much harder to observe (Morse et al. 2024). Thus, only three nests were observed, one of which was confirmed to have young (Figure 6). Birds began constructing nests as early as April 20. Adults were seen feeding fledged young through July 22. For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds).

Figure 4: Black-throated Green Warbler breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Black-throated Green Warbler breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Black-throated Green Warbler phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

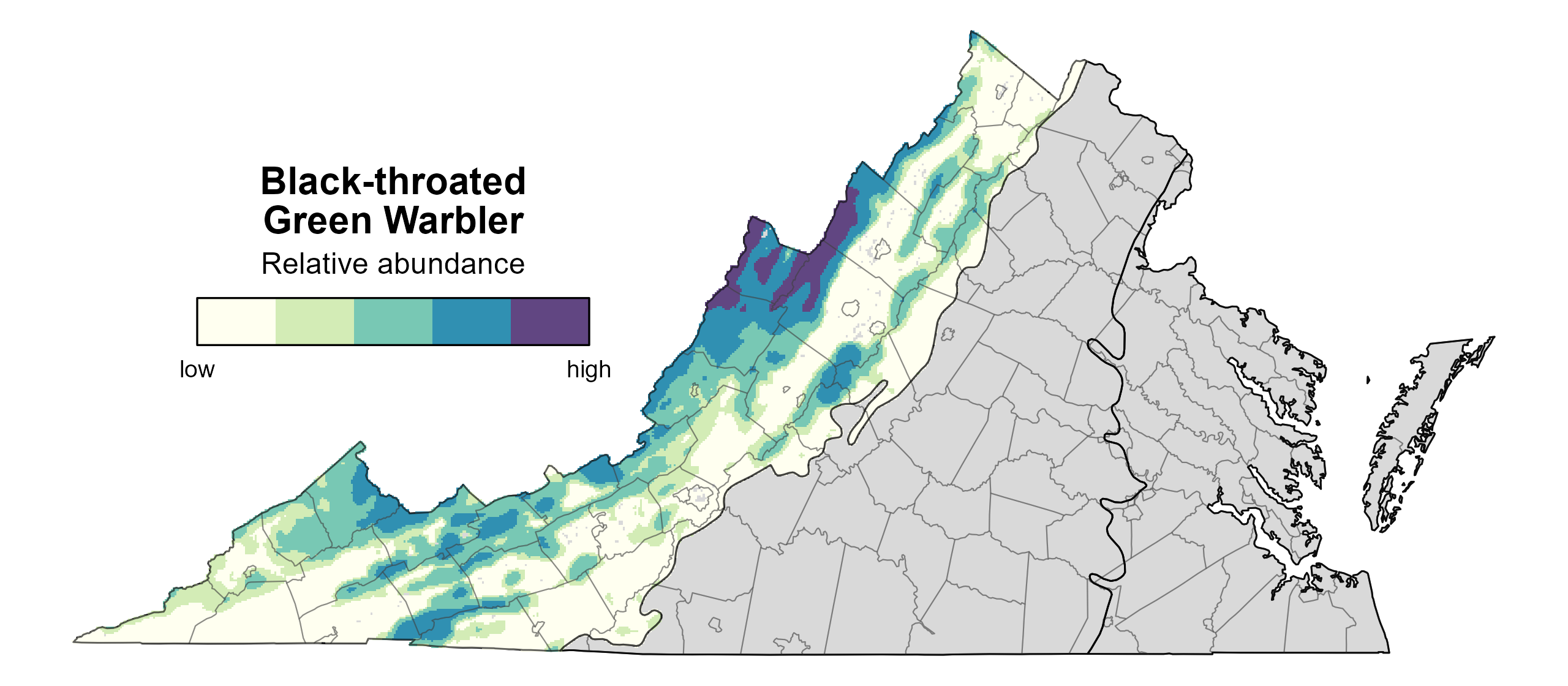

Black-throated Green Warbler predicted relative abundance was highest along major ridgelines in the Appalachian Mountains, particularly the Alleghany Mountain ridge along the Highland County-West Virginia border and Shenandoah Mountain in Augusta and Rockingham Counties (Figure 7).

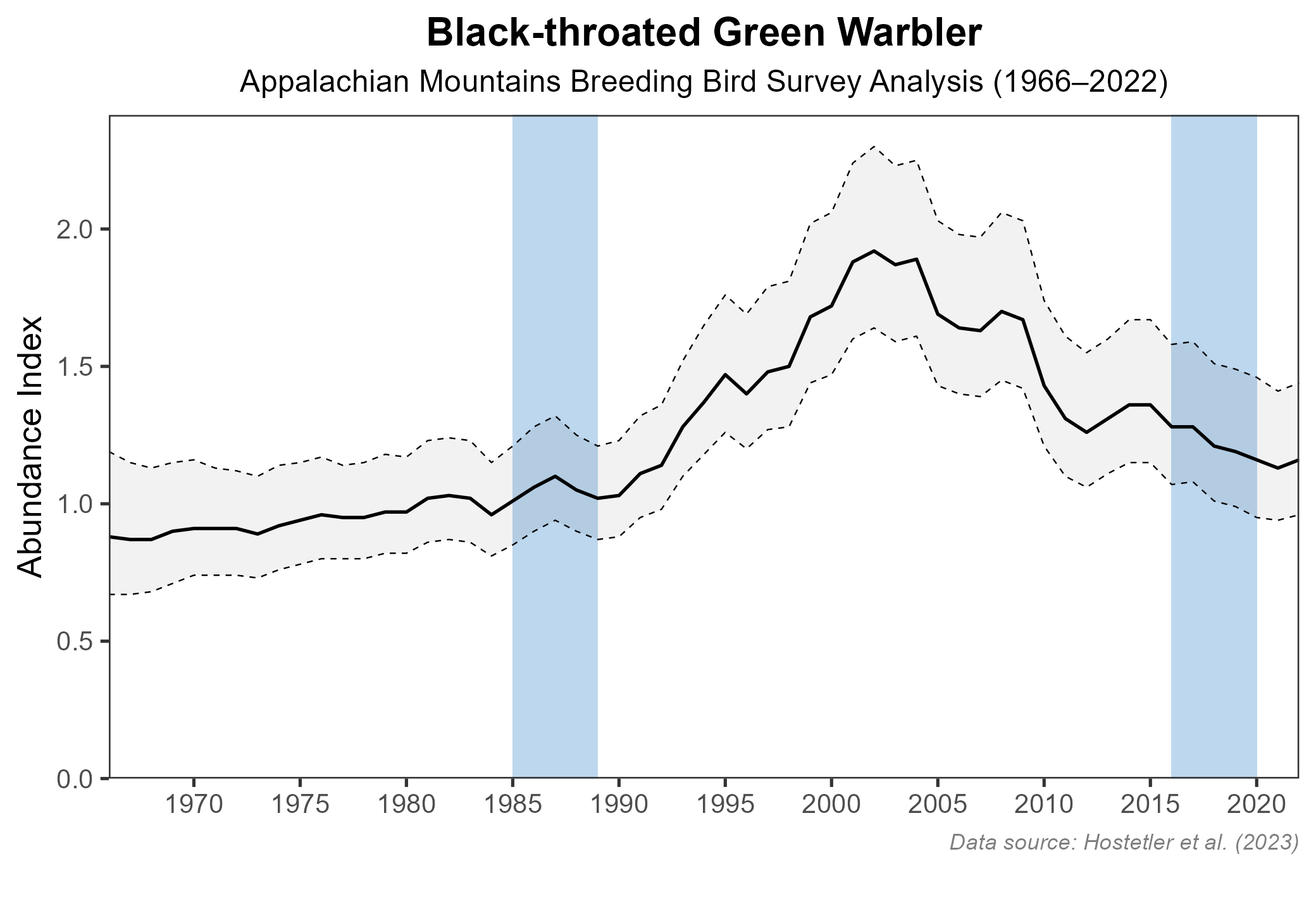

The total estimated Black-throated Green Warbler population in the Mountains and Valleys region is approximately 79,000 individuals (with a range between 47,000 and 136,000). Populations for the species appear stable. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) trend for the Appalachian Mountains Region (data for Virginia do not produce a credible trend) showed a nonsignificant increase of 0.47% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 8). Between the First and Second Atlas periods, the Appalachian Mountains population showed a similar nonsignificant 0.29% increase per year from 1987–2018. These estimates exclude Wayne’s Warbler, whose limited range suggests a more precarious status (see Conservation section), although a credible BBS trend is unavailable for the southeastern Coastal Plain region which it inhabits.

Figure 7: Black-throated Green Warbler relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high. Areas in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 8: Black-throated Green Warbler population trend for the Appalachian Mountains as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

The nominate subspecies of Black-throated Green Warbler is not of conservation concern and appears stable within its Appalachian range. In certain parts of that range, it has an association with Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) (Morse et al. 2024). Structural changes in mountain forests due to hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae) and balsam woolly adelgid (A. piceae) can modify breeding habitat for the species in regions not well-covered by the BBS (Morse et al. 2024). However, it is unclear to what extent the species is associated with and dependent on hemlock in Virginia.

Due to its small, range-restricted, and poorly understood population in the state, Wayne’s Warbler is classified in the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan as a Tier I Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Critical Conservation Need) (VDWR 2025). It has also been petitioned for listing under the Endangered Species Act (Harlan and Gaylord 2023). The subspecies has an extremely limited breeding distribution, being restricted to three states within the southeast Coastal Plain, with southeastern Virginia at its northern limit. Credible population trends for Wayne’s Warbler are not available. However, a 2001 survey for Wayne’s Warbler at the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge, where it was reported to be a relatively common breeder from the 1950s through 1970s, suggested a population decline there (Watts et al. 2011). Repeat surveys of the refuge in 2024, however, found Wayne’s Warbler across a relatively large swath that included several areas where it was locally abundant (Hines et al. 2024). The placement of the survey points and timing of the surveys in 2024 may have accounted for greater survey success. Surveys for Wayne’s Warbler are complicated by the fact that this subspecies nests relatively early, during a period when migrants of the nominate virens group are still passing through southeastern Virginia. This can lead to the potential misidentification of migrating virens as Wayne’s Warbler, although the 2024 surveys were designed to minimize this possibility (Hines et al. 2024).

Wayne’s Warbler may have historically been associated with extensive stands of Atlantic white cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides) in the southeastern Coastal Plain (Watts et al. 2011). However, its habitat preferences may have broadened since the near extirpation of white cedar patches throughout their range via harvesting. Wayne’s Warbler was not associated with any single tree species during the 2024 surveys and was generally found near trees with uneven canopies and little shrub cover (Chance Hines, personal communication).

Virginia surveys outside of the Great Dismal Swamp are ongoing. Continuing survey and research efforts in the Commonwealth, as well as in North Carolina and South Carolina, will improve the understanding of the subspecies’ population status, distribution, habitat preferences, and management needs (Hines et al. 2024). In addition, collecting movement data via nanotags would shed light on the migratory routes and overwintering areas used by the Wayne’s Warbler, as a path toward understanding potential threats to the bird away from its breeding grounds.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Carpenter, J. P., A. J. Worm, T. J. Boves, A. W. Wood, J. P. Poston, and D. P. L. Toews (2022). Genomic variation in the Black-throated Green Warbler (Setophaga virens) suggests divergence in a disjunct Atlantic Coastal Plain population (S. v. waynei). Ornithology 139:ukac033. https://doi.org/10.1093/ornithology/ukac033.

Harlan, W., and S. Gaylord (2023). Petition to list the coastal (Wayne’s) Black-throated Green Warbler (Setophaga virens waynei) under the Endangered Species Act as an endangered or threatened species and to concurrently designate critical habitat. Center for Conservation Biology, William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/birds/pdfs/2023-11-07-Coastal-Waynes-black-throated-green-warbler-petition.pdf.

Hines, C. H., L. S. Duval, and B. D. Watts (2024). Wayne’s Black-throated Green Warbler survey: 2024 report. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-24-10. William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. 25 pp.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Morse, D. H., J. P. Poston, P. Pyle, and A. F. Poole (2024). Black-throated Green Warbler (Setophaga virens), version 1.2. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald and N. D. Sly, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.btnwar.01.2.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Watts, B.D., Paxton, B.J. and Smith, F.M. (2011). Status and habitat use of the Wayne’s Black-throated Green Warbler in the northern portion of the South Atlantic Coastal Plain. Southeastern Naturalist 10:333–344.