Introduction

If warblers were gems, then the Prothonotary Warbler would be a crown jewel. It holds a unique place in American history: during the trial of alleged spy Alger Hiss, his claim of seeing a Prothonotary Warbler along the Potomac River played a key role in his conviction (Linder, n.d.).

This species is closely tied to flooded bottomland hardwood forests. As Virginia’s only cavity-nesting warbler, the Prothonotary Warbler depends on natural cavities or those excavated by Downy Woodpeckers (Picoides pubescens) (Petit 2020). The species is also happy to accept nest boxes installed by humans, facilitating the study of its breeding ecology, particularly in Virginia (e.g., Blem and Blem 1992). Nonetheless, its reliance on specialized habitat and limited cavity resources makes it vulnerable to changes in hydrology and therefore a useful indicator species for forested wetlands.

Breeding Distribution

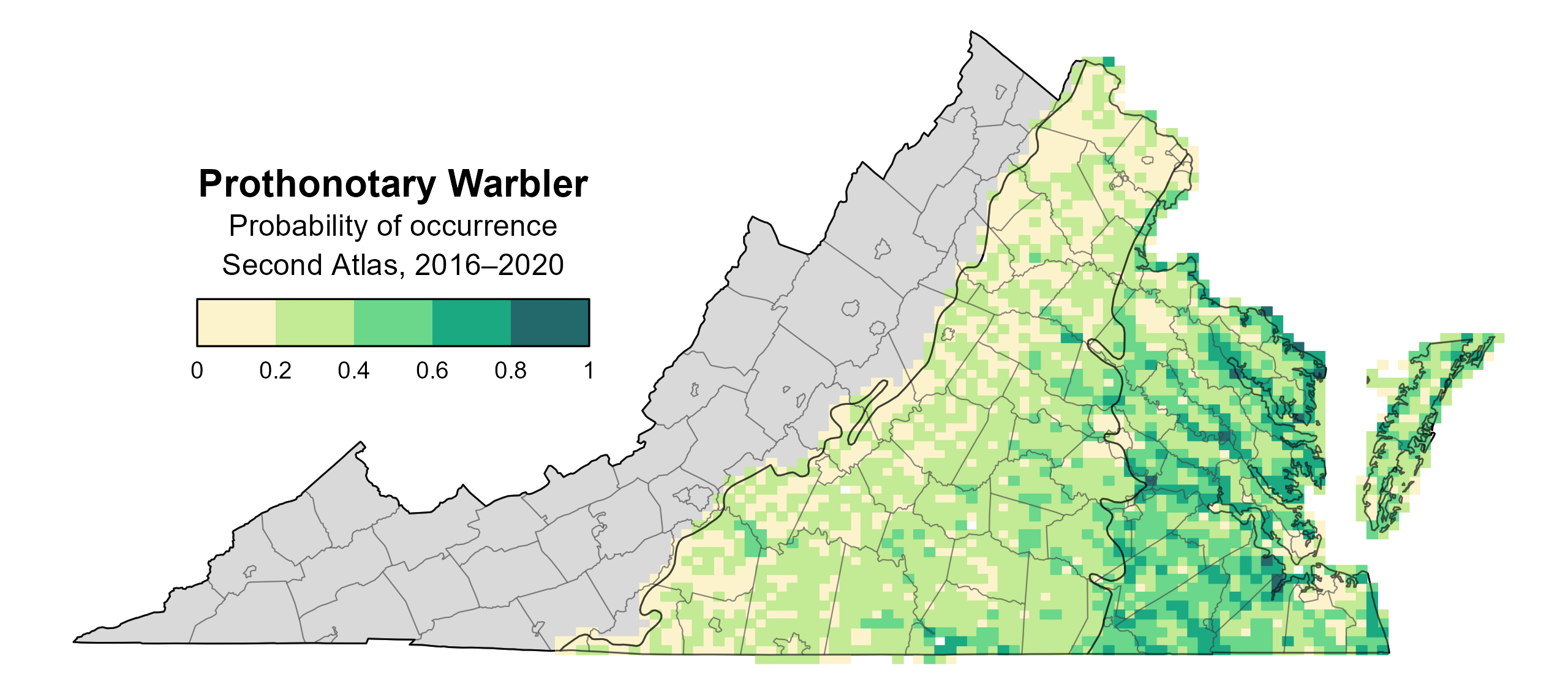

Prothonotary Warblers occur primarily in the Coastal Plain region and on interior waterways in the Piedmont (Figure 1). Wetlands and waterway margins provide the habitat they require for breeding, and these habitats can occur even into the Mountains and Valleys region (though these rare records could not be modeled; see the Breeding Evidence section). While urban and inland areas are less likely to support the species, it can persist in forested parks along major rivers, even in highly urbanized regions such as Hampton Roads and Northern Virginia. Because the species is so reliant on wetlands and waterways, two habitat features not included in the Second Atlas models, its distribution could not be predicted as accurately as many other species, and the model is considered weak (see Analytical Methods). However, occupancy was higher in blocks with a greater number of habitat types, likely capturing the presence of aquatic habitats.

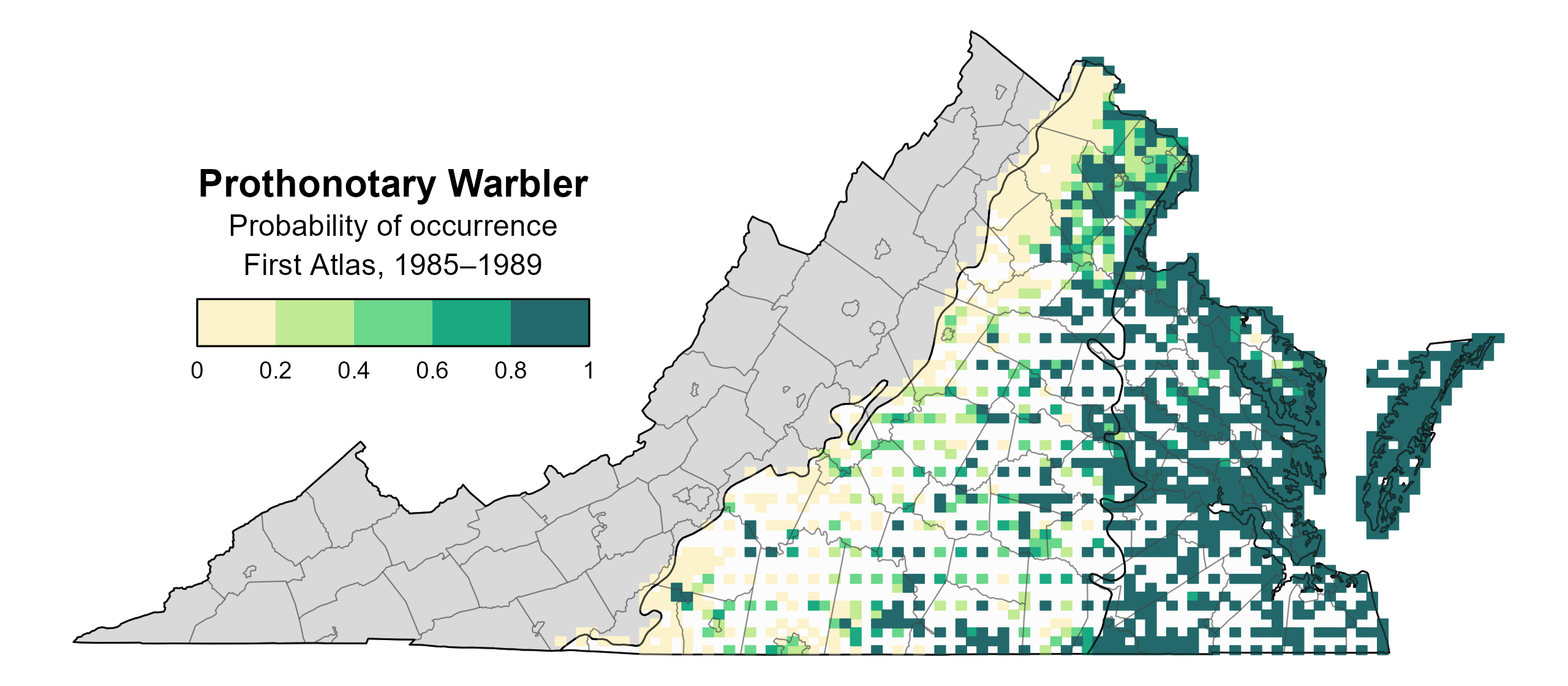

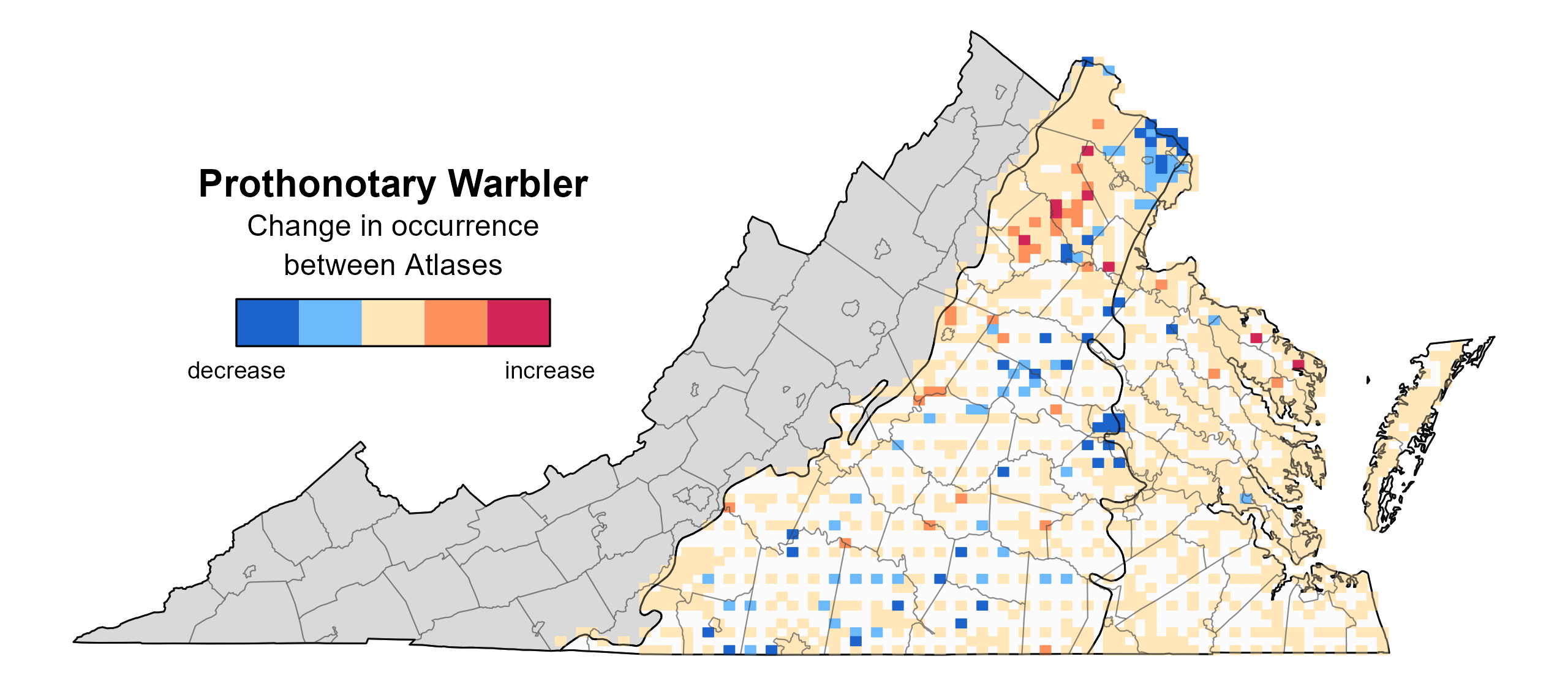

The Prothonotary Warbler’s likelihood of occurrence during the Second Atlas was broadly similar to that during the First Atlas (Figures 1 and 2). However, the species is now less likely to be found in urbanized areas of Northern Virginia and Richmond (Figure 3).

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Prothonotary Warbler breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 2: Prothonotary Warbler breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Prothonotary Warbler change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

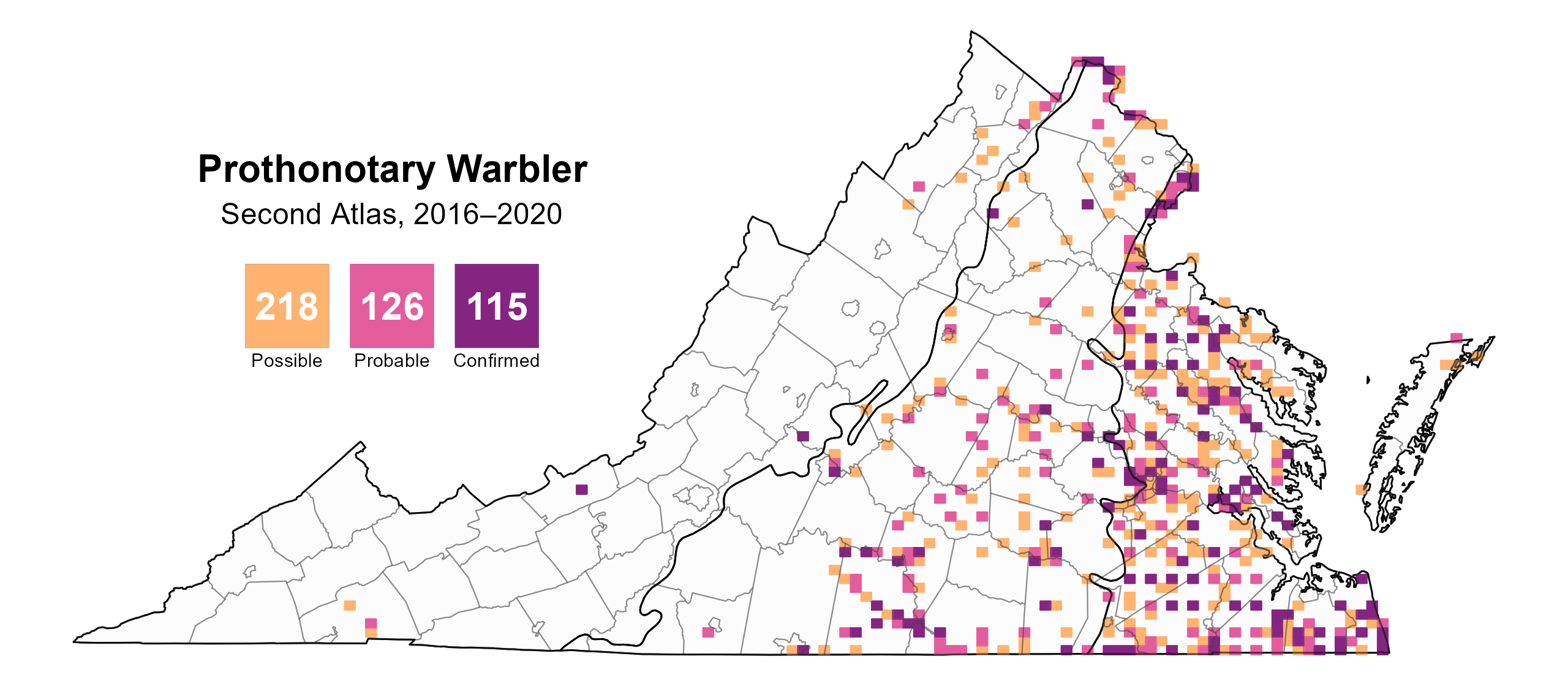

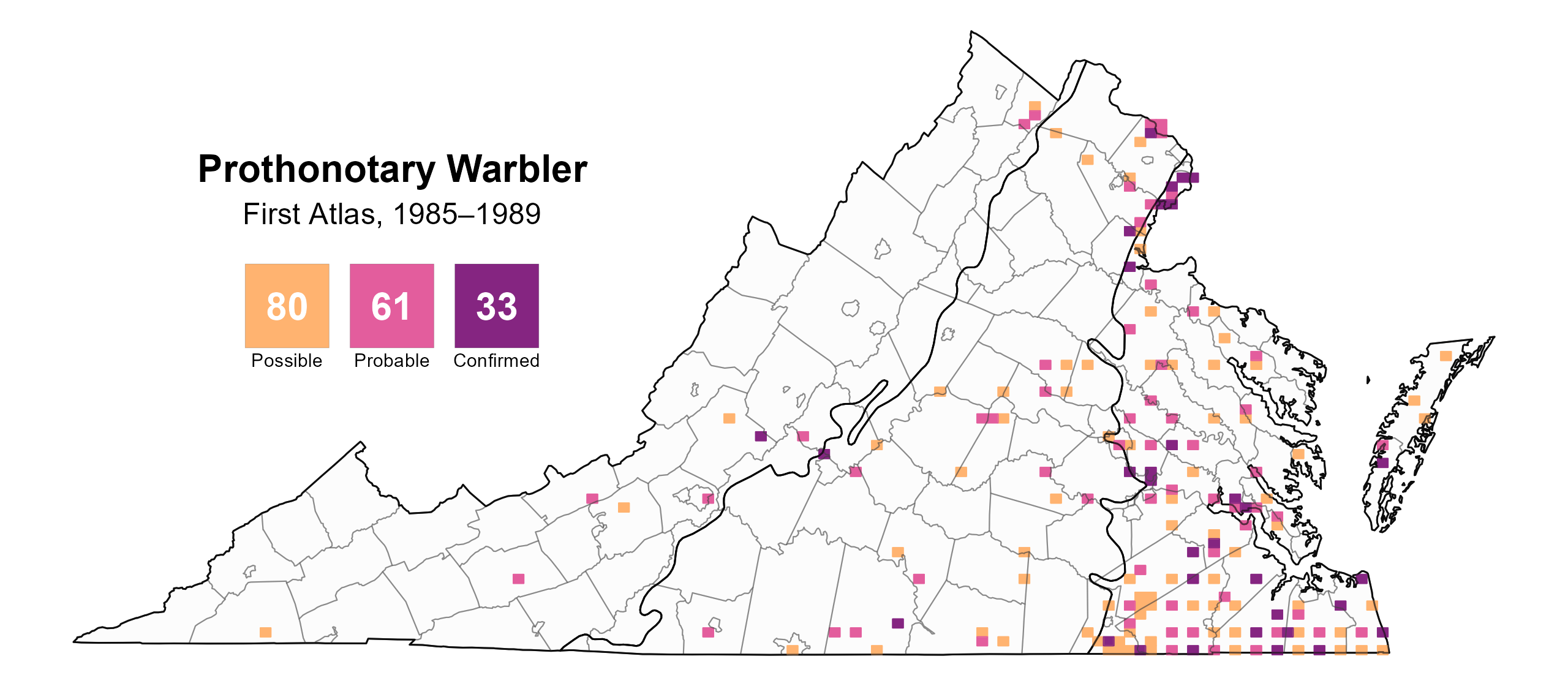

Prothonotary Warblers were confirmed breeders in 115 blocks and 42 counties and probable breeders in an additional 24 counties (Figure 4). They were not entirely restricted to the Coastal Plain region and were found along rivers all the way into the Mountains and Valleys region, including along the New River in Giles County and the James River in Amherst County. They were additionally present as probable breeders along the Holston River in Washington County, a tributary which lead to the Tennessee River. Although Prothonotary Warblers are not common in the mountains, they can evidently occur there along any suitable river with floodplains, and historically, they were common along the upper James River (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). During the First Atlas, several breeding observations were also recorded in the Mountains and Valleys region as well as in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions (Figure 5).

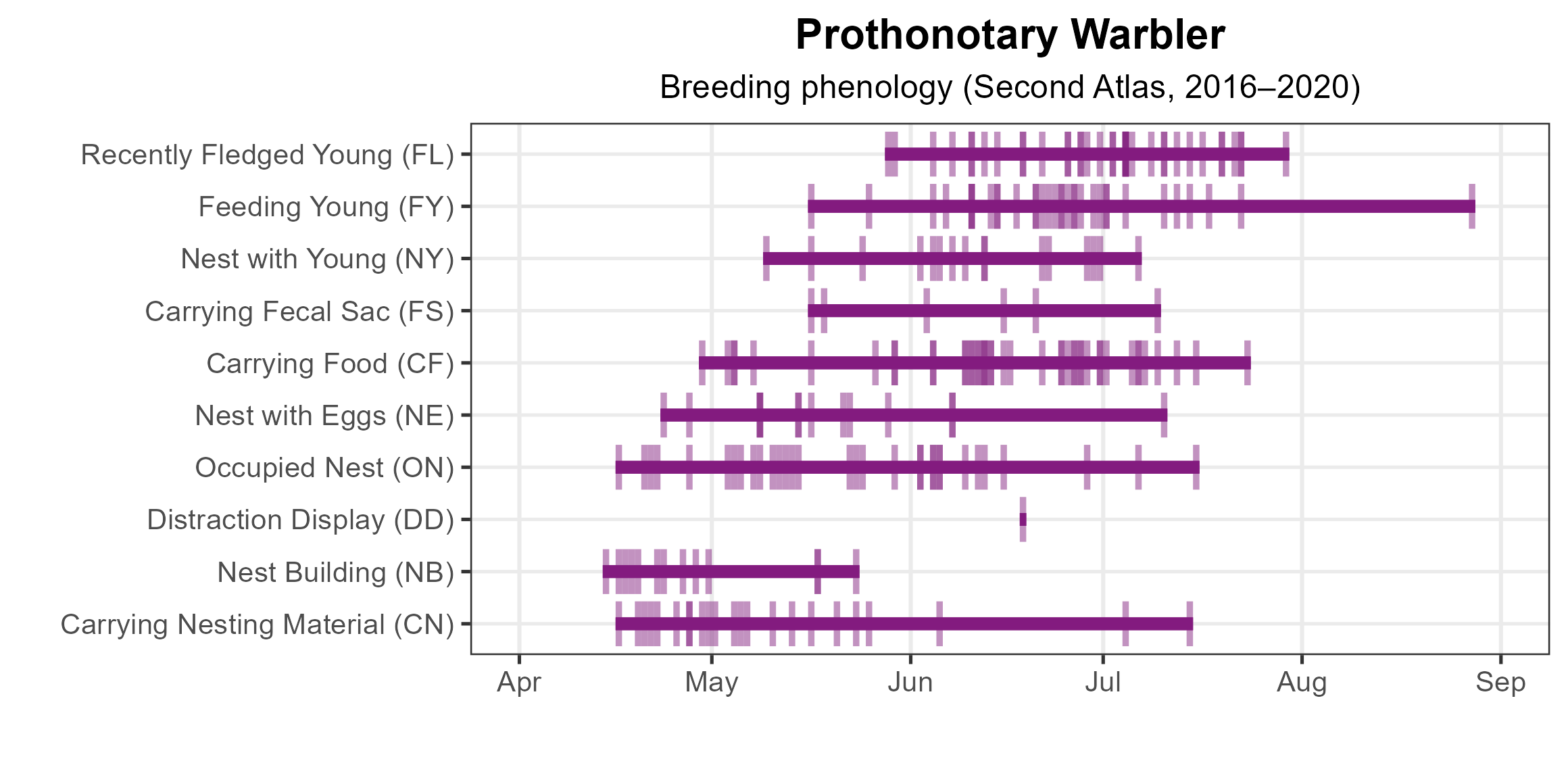

Most breeding confirmations were from adults carrying food or observations of recently fledged young, as Prothonotary Warbler nests are typically only accessible by boat. Unlike other cavity-nesting species however, Prothonotaries were confirmed by every type of breeding behavior (Figure 6). Nest box monitoring programs contributed a great deal to the broad spectrum of behaviors and nest stages that were observed, particularly nests with eggs. Birds began constructing nests as early as April 14, with the first eggs observed on April 23. Breeding continued to be recorded through August, with one late record of an adult feeding young on August 27. For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Prothonotary Warbler breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Prothonotary Warbler breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Prothonotary Warbler phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

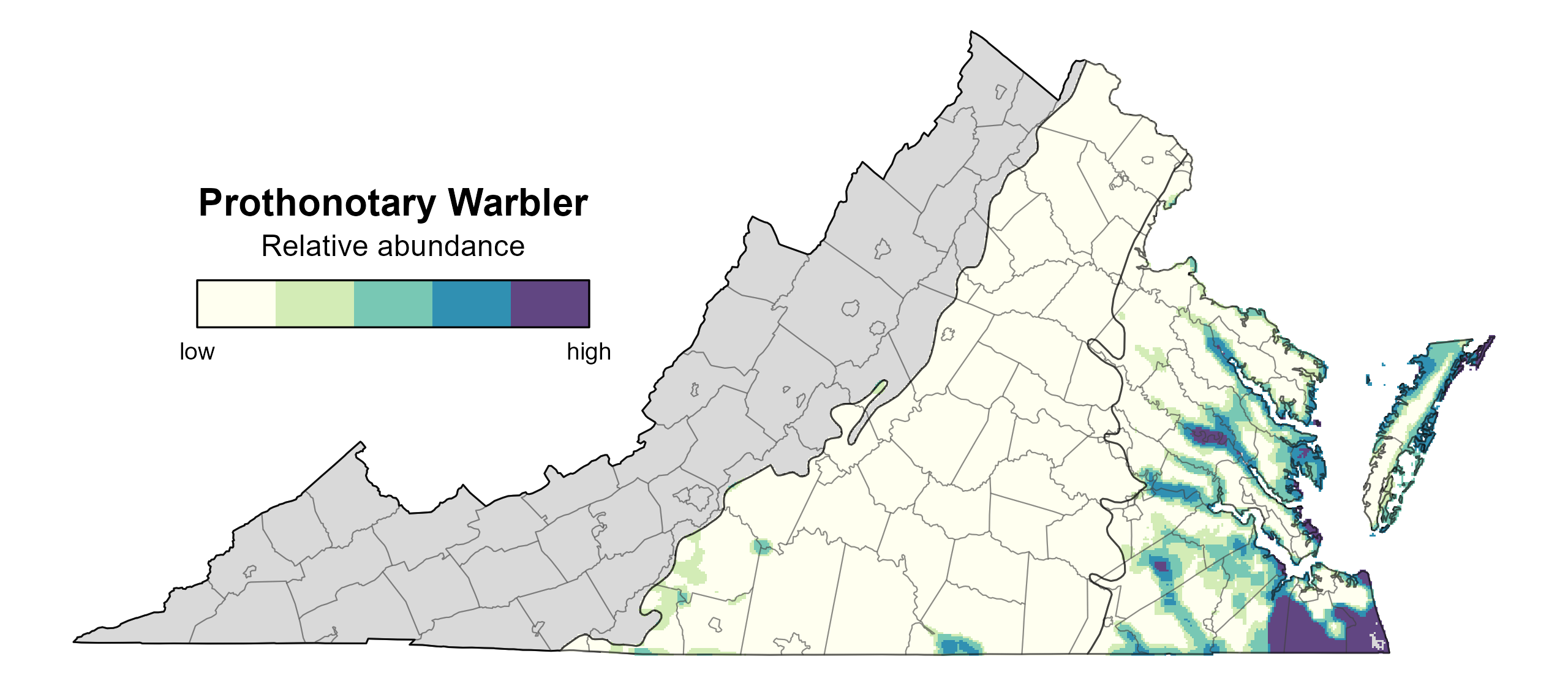

Prothonotary Warbler relative abundance was estimated to be highest along rivers in the Coastal Plain, particularly in the Great Dismal Swamp (Figure 7). Its highest abundance in Virginia, and perhaps range-wide, was previously recorded along the lower James River (Petit 2020).

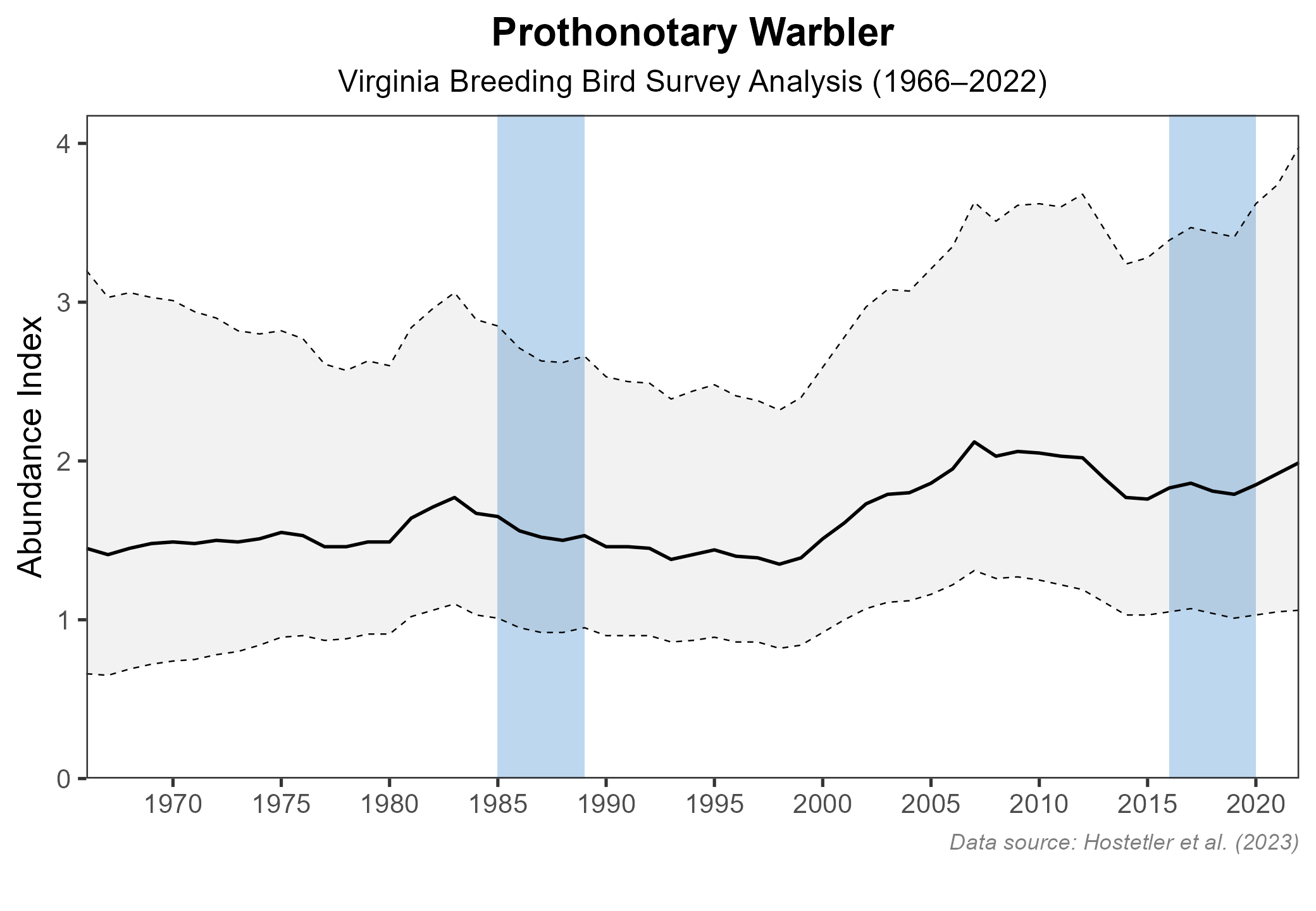

The total estimated Prothonotary Warbler population in the state is approximately 26,000 individuals (with a range between 12,000 and 55,000). Populations appear stable in Virginia. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) showed the species’ population experienced a nonsignificant increase of 0.61% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 8). Between the Atlas periods, its population showed a similar nonsignificant 0.57% annual increase per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 7: Prothonotary Warbler relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high. Areas in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 8: Prothonotary Warbler population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

While not a species of conservation concern in Virginia, Prothonotary Warblers remain vulnerable to the loss of snags and natural cavities in wetland habitats. Their willingness to use nest boxes provides a practical tool for local conservation efforts, particularly in areas where natural nest sites such as standing dead trees have been lost.

Nest box programs, such as those led by Virginia Commonwealth University, the Coastal Virginia Wildlife Observatory, and Virginia Bluebird Society, alongside local volunteer efforts, have enhanced populations and raised public awareness about wetland conservation (e.g., Brown 2024). Maintaining and expanding such efforts will be important for safeguarding local populations and their habitats.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Blem, C. R., and L. B. Blem (1992). Prothonotary Warblers nesting in nest boxes: clutch size and timing in Virginia. The Raven 63:15–20.

Brown, C. (2024). A bird call for wetland health. Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA. https://magazine.vcu.edu/2024-summer/a-bird-call-for-wetland-health/.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Linder, D. O. n.d. The warbler that made two presidents. Famous Trials. University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. https://www.famous-trials.com/algerhiss/657-warbler.

Petit, L. J. (2020). Prothonotary Warbler (Protonotaria citrea), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.prowar.01.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.