Introduction

The bulk of the feisty Marsh Wren’s breeding distribution lies north and west of Virginia, though the species is widespread throughout marshes of the Chesapeake Bay (Wilson et al. 2007). The male’s bubbly, gurgling song is distinctive within freshwater and saltwater marshes, where it builds several dome-shaped nests amid stems of marsh grasses. Males escort females to multiple nests until one is chosen, and together, they begin to fiercely defend their territory. The male, however, can have multiple mates (Kroodsma and Verner 2020). Males and females sometimes destroy the nests and eggs of other Marsh Wrens and even other wetland bird species (Kroodsma and Verner 2020).

Breeding Distribution

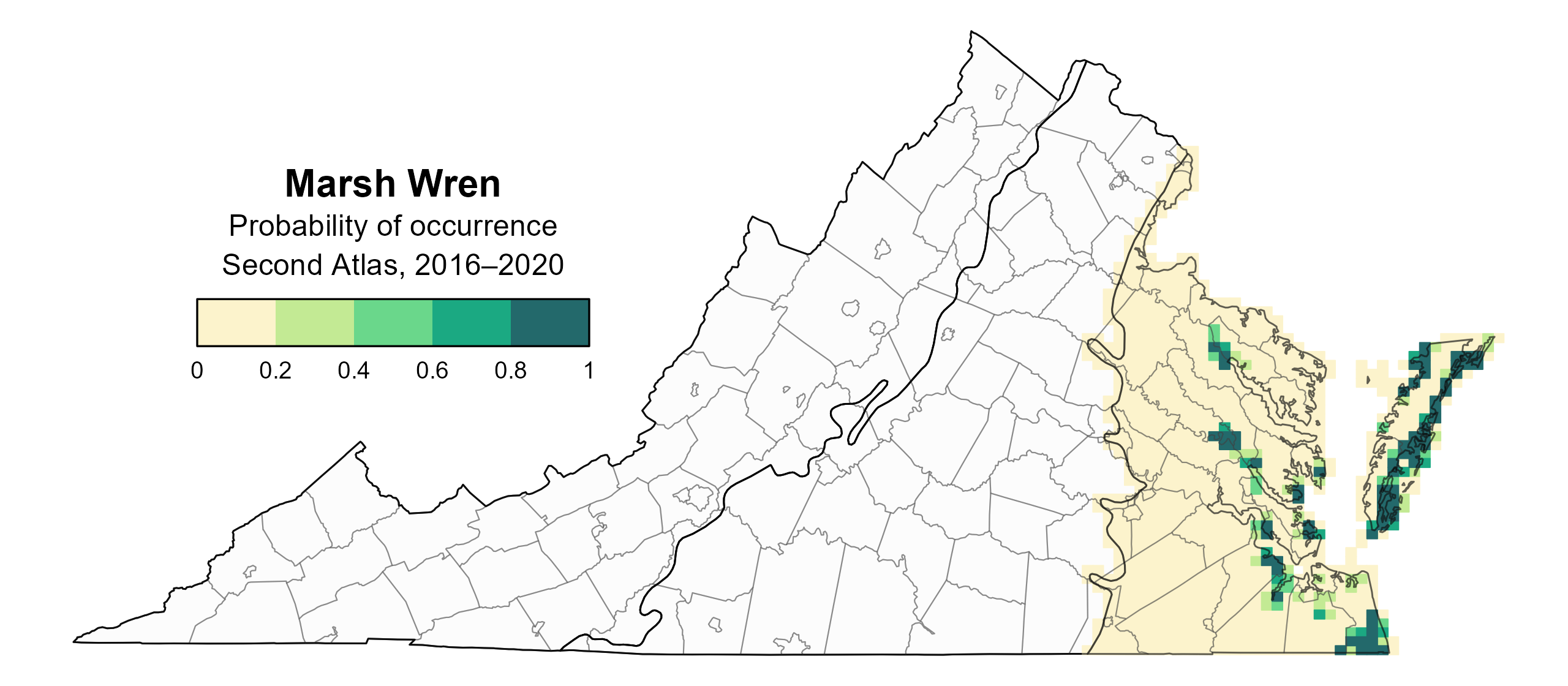

Marsh Wrens breed almost exclusively within the Coastal Plain region, including marshes on the bayside and seaside of the Eastern Shore, in the Back Bay/North Landing River area, and across salinity gradients in the tidal zones of the major tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay (Figure 1). As would be expected for a species that nests only in marshes, the likelihood of Marsh Wrens occurring in a block increases as the amount of marsh increases; however, the maximum predicted likelihood that the species will occur in any given block is relatively low at 50%.

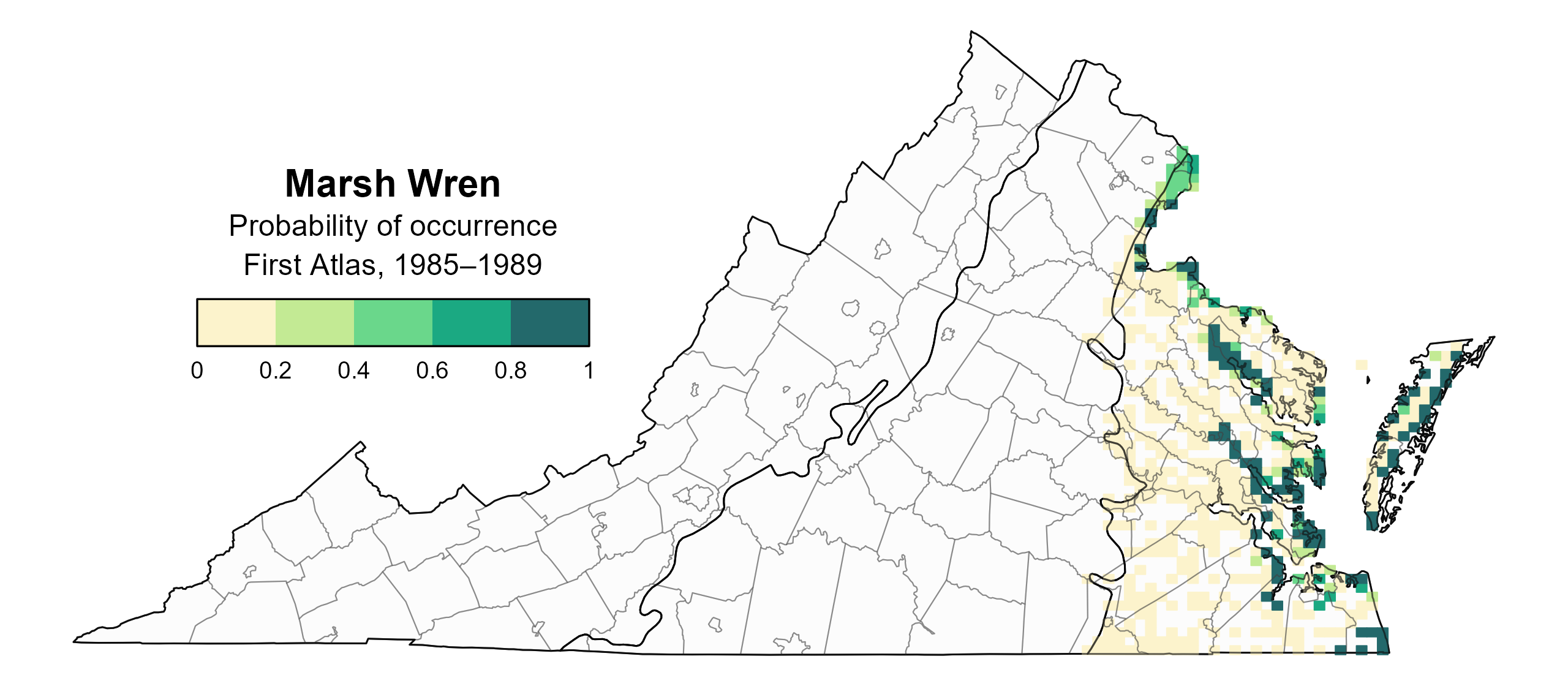

Between Atlases (Figures 1 and 2), Marsh Wrens became less likely to be found in higher salinity marshes, including those on the Eastern Shore and in major tributaries, and in freshwater marshes of the upper Potomac River (Figure 3).

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Marsh Wren breeding distribution based on predicted occurrence (Second Atlas 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 2: Marsh Wren breeding distribution based on predicted occurrence (First Atlas 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Marsh Wren change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

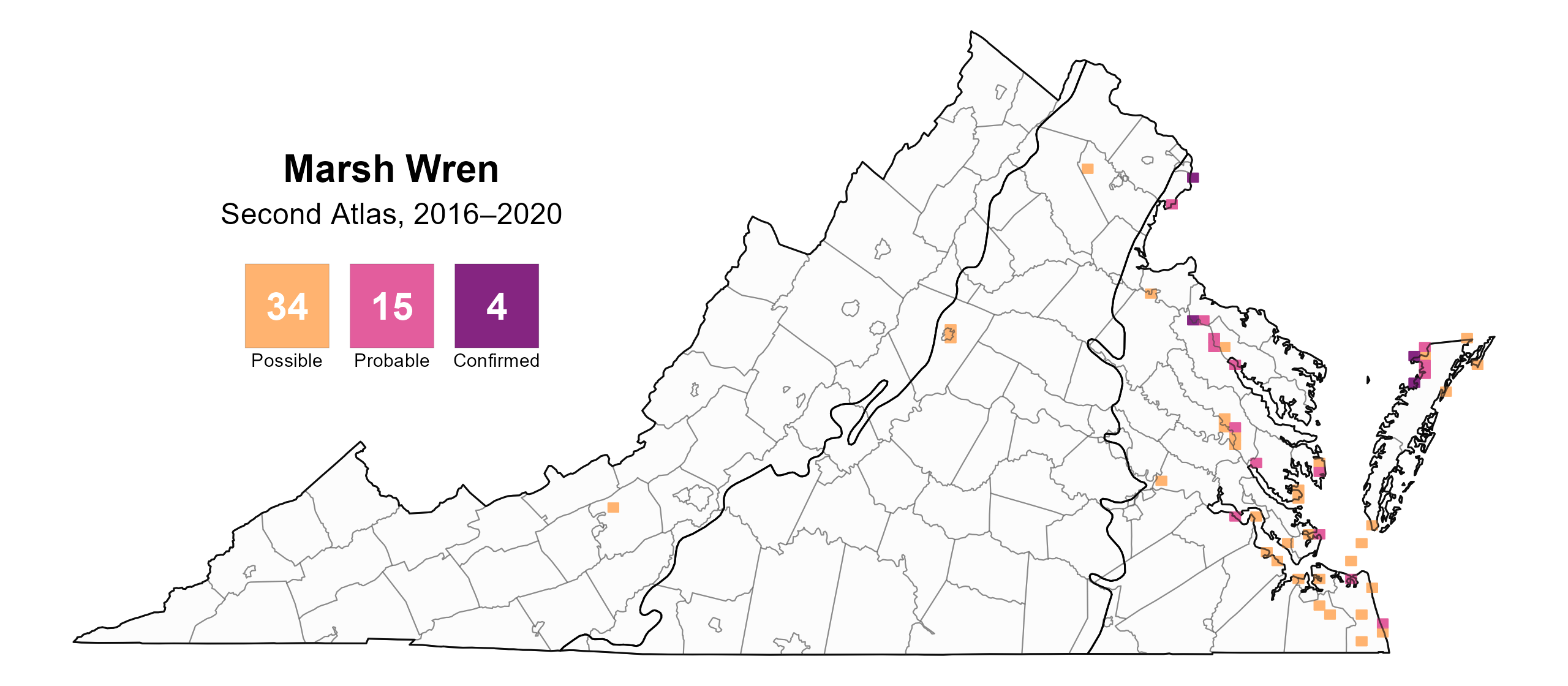

Marsh Wrens were confirmed breeders in four blocks in three counties, including at Saxis Wildlife Management Area and Marks and Jacks Islands State Natural Area Preserve in Accomack County, Dyke Marsh Wildlife Preserve in Fairfax County, and Drake Marsh on the Rappahannock River in Westmoreland County (Figure 4). They were found to be probable breeders in eight additional counties.

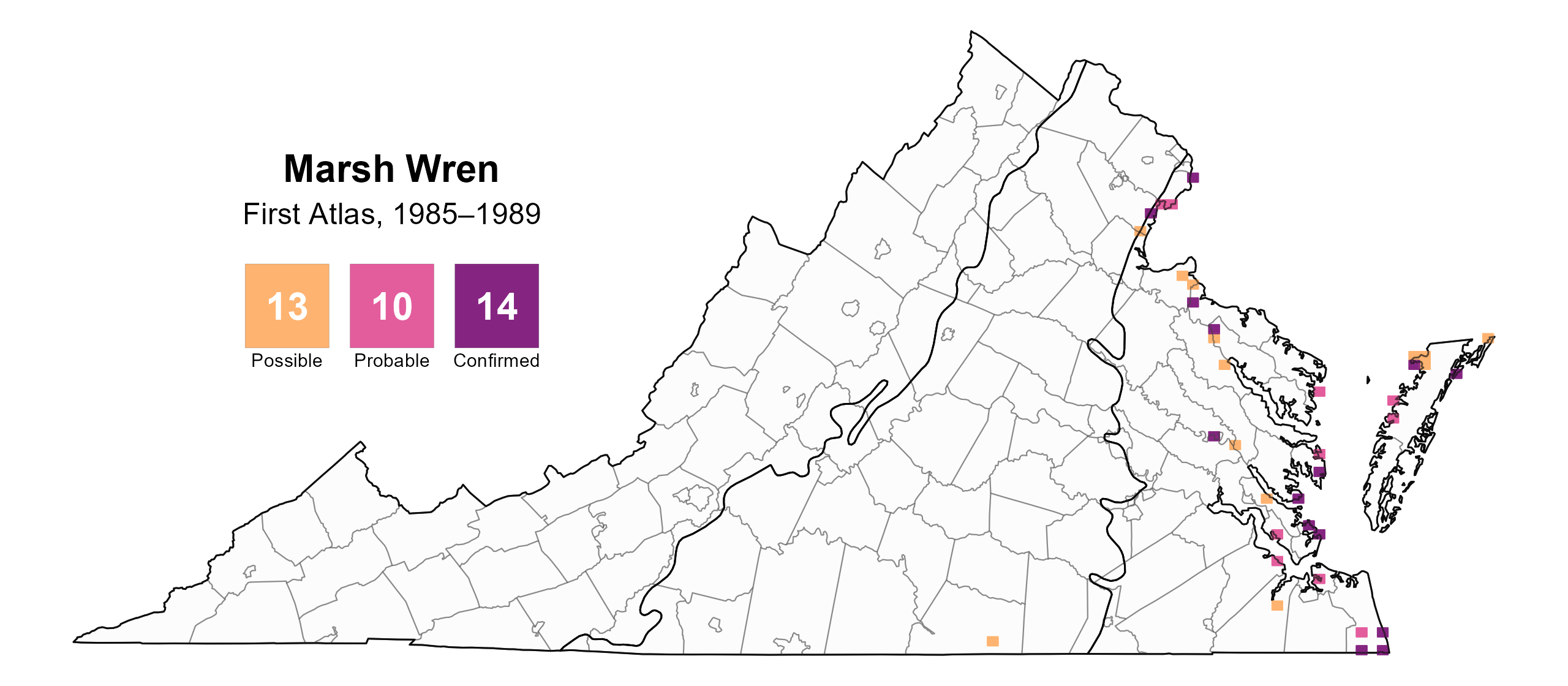

As with other species strongly tied to marshes, records of Marsh Wrens reported by volunteers were relatively few, given the difficulty in accessing marshes from land, and some of the few confirmed breeding observations were obtained by boat. Outside of the Coastal Plain, the species has been previously reported as breeding locally at Kerr Reservoir in the southern Piedmont region and near Dulles Airport in the northern Piedmont region (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). Several observations in Albemarle, Montgomery, and Prince William Counties during the Second Atlas were of possible breeders. During the First Atlas, there were more confirmed breeders than during the Second Atlas (Figure 5).

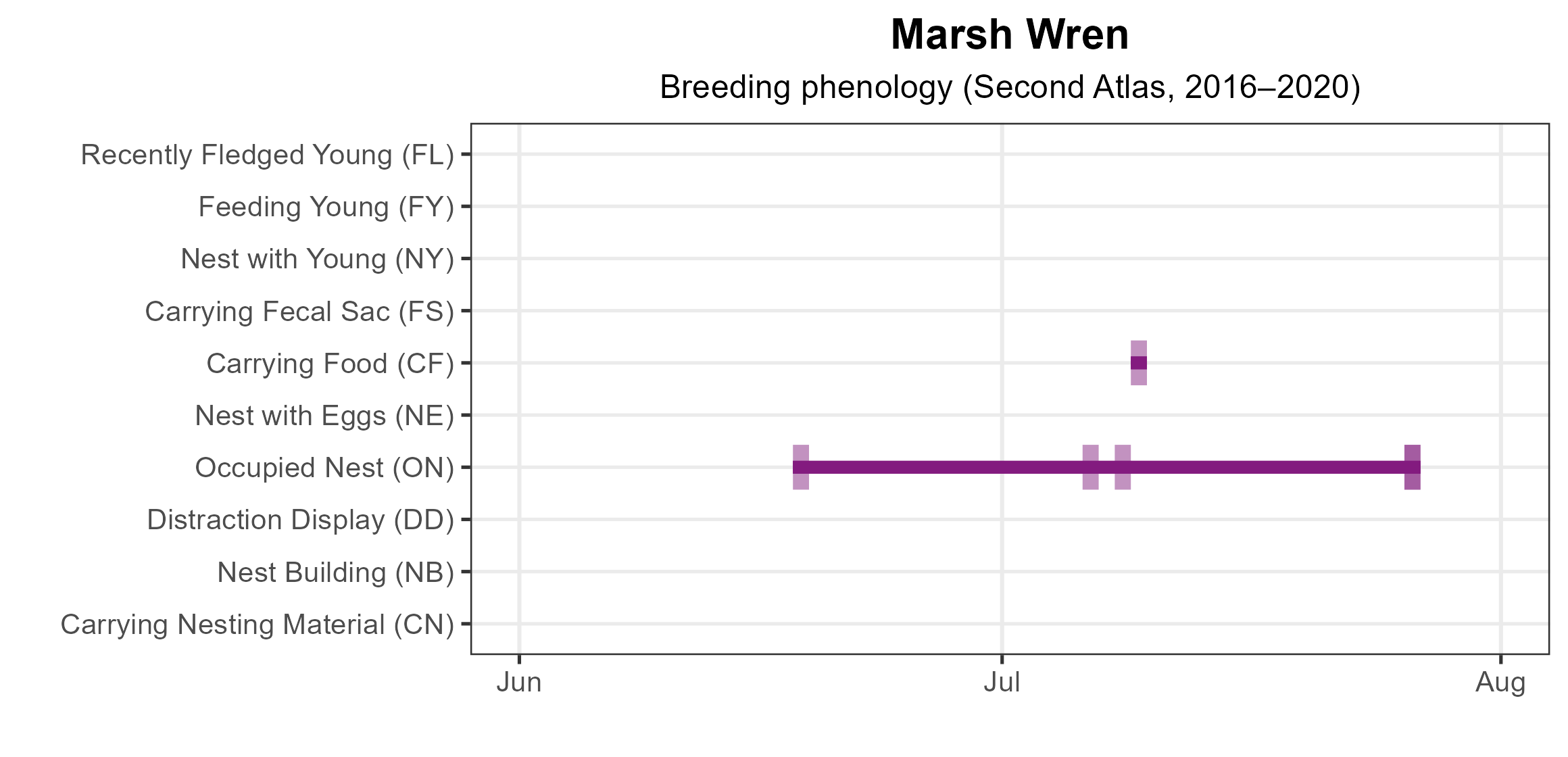

Five of the six Marsh Wren confirmed breeding records consisted of occupied nests, which were observed between June 18 and July 26. The sixth confirmation stemmed from observing an adult carrying food on July 9 (Figure 6).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Marsh Wren breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Marsh Wren breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Marsh Wren phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Marsh Wrens were only recorded at three points during the point count surveys, such that an abundance model for the species could not be developed. However, the species is believed to be generally more abundant in freshwater and brackish marshes of the Chesapeake Bay, where there is greater cover of the taller marsh grass species, such as big cordgrass (Spartina cynosuroides), that they prefer for nesting (Wilson et al. 2007).

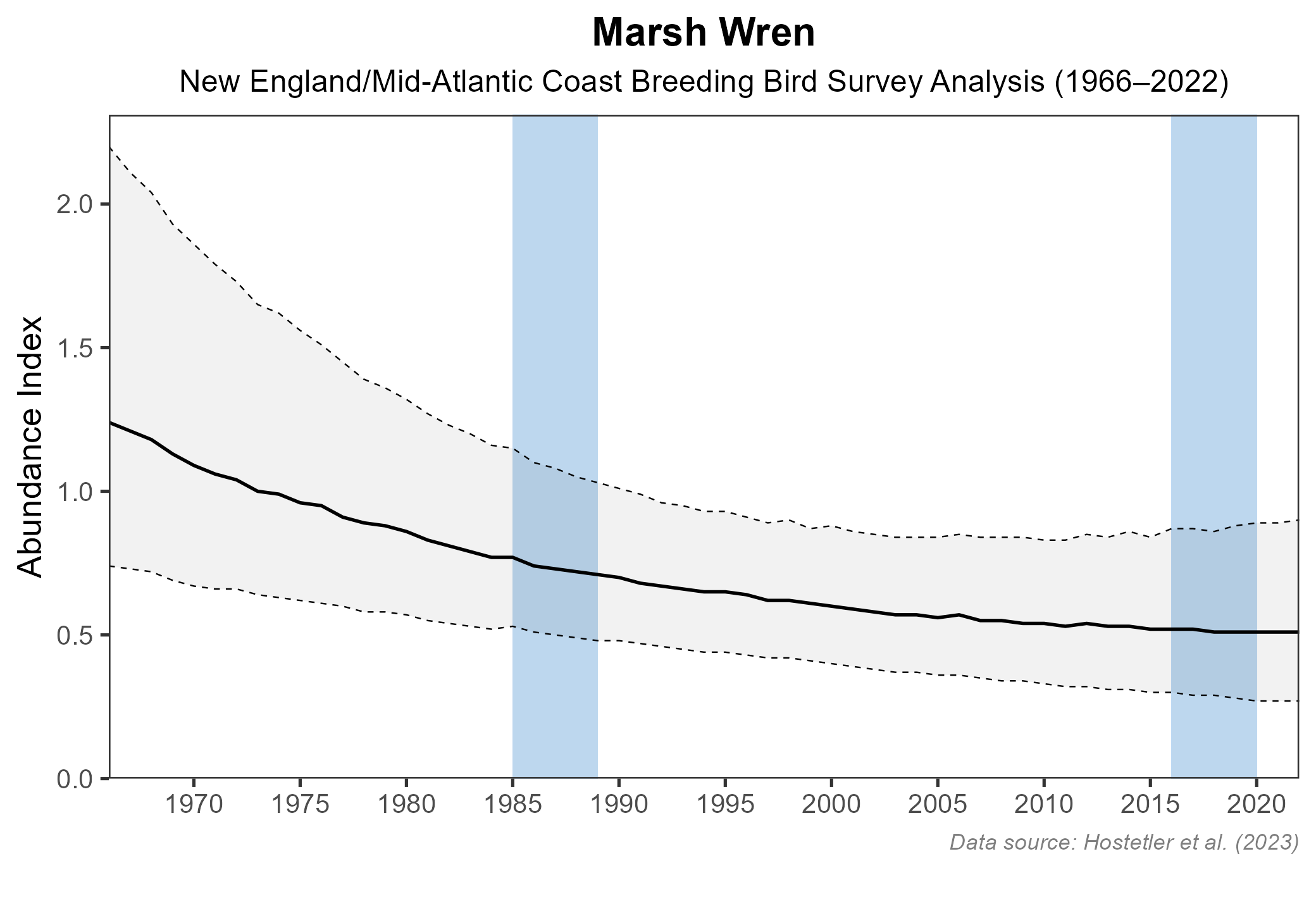

Although a credible population trend for Virginia cannot be estimated from the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), BBS data for the broader New England/Mid-Atlantic Coast region showed a significant decrease of 1.54% per year from 1966–2022 in that region (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 7). Between Atlases, BBS data showed a nonsignificant decline of 1.16% per year from 1987–2018.

Marsh bird surveys conducted on the Western Shore in 2021 by the Center for Conservation Biology at the College of William and Mary estimated a 90% decline in the species in Virginia salt marshes since 1992, with mean abundance having decreased over ninefold over that period (Watts 2025).

Figure 7: Marsh Wren population trend for the New England/Mid-Atlantic region as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line represents the estimated population trend; the dashed lines represent the upper and lower values within which there is 97.5% confidence that the true population trend line falls. The vertical light blue bars represent the periods corresponding to the First and Second Atlases.

Conservation

Given their ongoing decline, Marsh Wrens are identified as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need Tier III (High Conservation Need) in the Virginia Wildlife Action Plan (VDWR 2025). Identification and protection of existing suitable marshes will be necessary to ensure that a supply of adequate habitat persists for this species, especially as coastal marshes subside or are threatened with sea-level rise (VDWR 2025). Similarly, identification and protection of properties in marsh migration zones, where upland habitats have a high probability of transforming into suitable marsh habitats, may be important for the long-term conservation of this and other marsh-breeding species (VDWR 20225).

Since 1992, an estimated 16,000 acres (6,475 hectares) of new marsh have been created in the lower Chesapeake Bay of Virginia through natural marsh migration mediated by sea-level rise(Mitchell et al. 2021). These marshes occupy areas that were once forests, lawns, and agricultural fields, but the habitat benefits that they provide to marsh birds may be variable (Mitchell et al. 2021). Marsh Wrens can also benefit from marsh management targeting common reed (Phragmites australis), a nonnative invasive species in the Chesapeake Bay that negatively impacts the species (Paxton and Watts 2002). Marsh Wrens along the Atlantic Coast are classified as partial migrants (Kroodsma and Verner 2020), given that a portion of the population is migratory and the other is sedentary. In Virginia, the latter may be concentrated along the coastline, where the species is considered an uncommon winter resident (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). Investigating the migratory status of Virginia’s Marsh Wrens and where they migrate may shed light on whether potential threats to the species should be investigated on wintering grounds outside of Virginia.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Kroodsma, D. E. and J. Verner (2020). Marsh Wren (Cistothorus palustris), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.marwre.01.

Mitchell, M., B. Watts, J. Hendricks, K. Angstadt, D. Stanhope, D. M. Bilkovic, P. Mason (2021). Strategy development to enhance the conservation and adaptation of Virginia coastal wetlands under climate change. Virginia Institute of Marine Science and Center for Coastal Resources Management. 18 pp.

Paxton, B. J., and B. D. Watts (2002). Bird surveys of Lee and Hill Marshes on the Pamunkey River: possible effects of sea-level rise on marsh bird communities. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series. CCBTR-03-02. College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Rottenborn, Stephen C, and Edward S Brinkley, eds. 2007. Virginia’s Birdlife: An Annotated Checklist. 4th ed. Virginia’s Avifauna, No. 7. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Watts, B. D. (2025) Decline of salt marsh-nesting birds within the lower Chesapeake Bay (1992–2021). PLoS One 20:e0323254.

Wilson, M.D., B.D. Watts, and D.F. Brinker (2007). Status review of Chesapeake Bay marsh lands and breeding marsh birds. Waterbirds 30: 122–137.