Introduction

The Blue-gray Gnatcatcher is a common bird that dashes between treetops across the Commonwealth from spring to fall. One of our earlier-arriving migrants, the species quickly fills woodlands with its dry, nasal spee calls. It is commonly found loudly scolding or mobbing predators, and its noisiness is commensurate with its strong personality. Blue-gray Gnatcatchers are pugnacious despite their small size: they will attack all large birds, including nonpredators, and will even steal nest material from other species (Kershner and Ellison 2020). Their tidy nests, composed of lichen and webbing, are well-disguised but prolific (Kershner and Ellison 2020). Blue-gray Gnatcatchers in the eastern portion of their range generally breed in deciduous and mixed forests, often including oak-hickory communities or riparian areas. Within this habitat, the species favors gaps and edges (Kershner and Ellison 2020).

Breeding Distribution

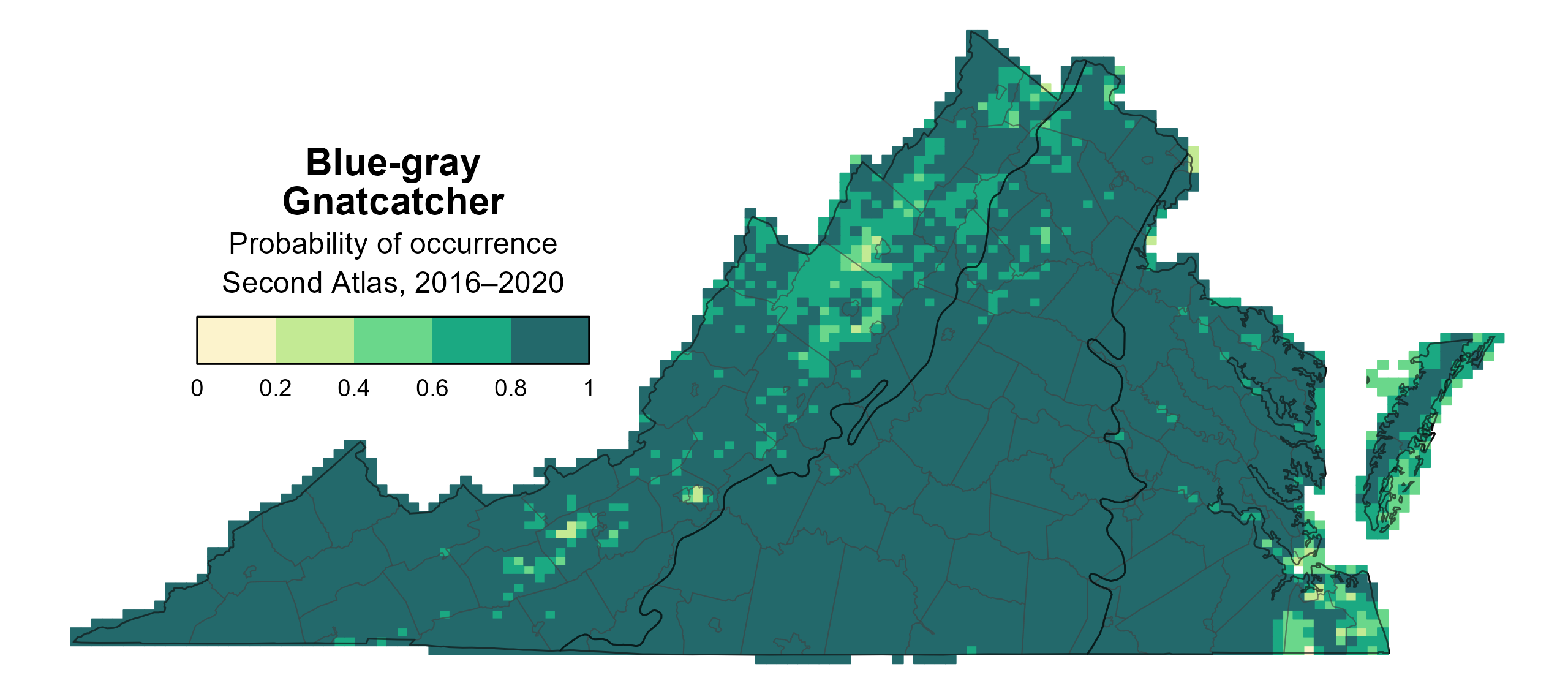

Blue-gray Gnatcatchers are found across the state; however, the likelihood that this species occurs in the southern Shenandoah Valley and the Hampton Roads area is marginally lower than that in the rest of the state (Figure 1). In the Mountains and Valleys region, they typically breed below 3,500 ft (1,067 m) in elevation (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). Blue-gray Gnatcatchers are also slightly positively associated with edge habitat, while they slightly negatively associated with agricultural and developed lands. Notably, even the lowest predicted occurrence value was over 20%, indicating that with a suitable habitat patch, they can occur as a breeder in much of the state. Exceptions occur in the southeastern portion of the state, where habitat can lack breeding Blue-gray Gnatcatchers if surrounded by suburban areas. Breeders are also scarce in the Great Dismal Swamp, a large contiguous forested wetland, perhaps due to the lack of edge habitat.

Blue-gray Gnatcatcher distribution during the First Atlas and its change between the two Atlas periods could not be modeled due to data and model limitations (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on its distribution during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Blue-gray Gnatcatcher breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Breeding Evidence

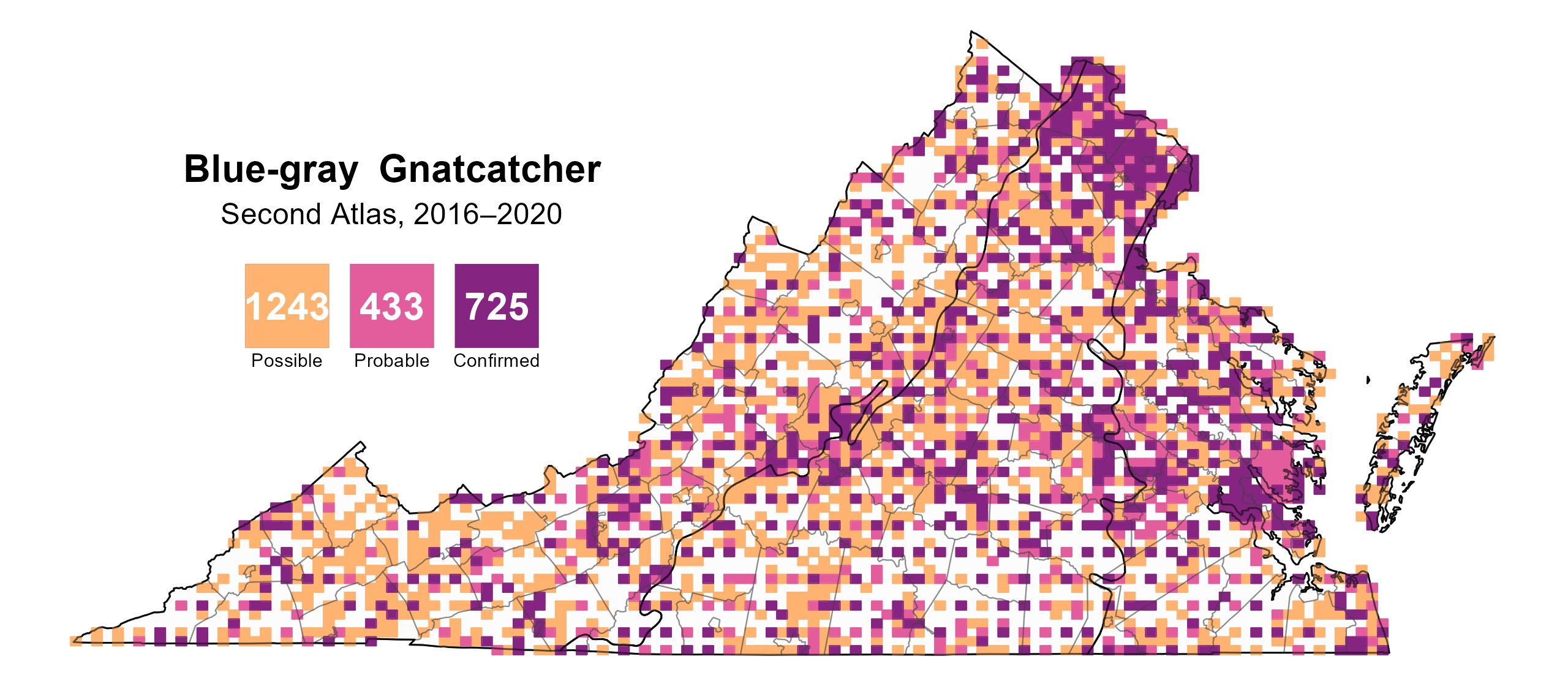

Blue-gray Gnatcatchers were confirmed breeders in 725 blocks and 114 counties and probable breeders in six additional counties (Figure 2). Confirmations were particularly concentrated in the northern part of Virginia and the central Coastal Plain region. This species was also a confirmed breeder throughout the state during the First Atlas (Figure 3).

Blue-gray Gnatcatchers are migratory, arriving at the end of March and quickly initiating nesting activities. Breeding was confirmed from March 29 (nest building) to August 17 (feeding young) (Figure 4). Observers documented Blue-gray Gnatcatchers performing every type of breeding activity, although only one nest with eggs was found. For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Blue-gray Gnatcatcher breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Blue-gray Gnatcatcher breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Blue-gray Gnatcatcher phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

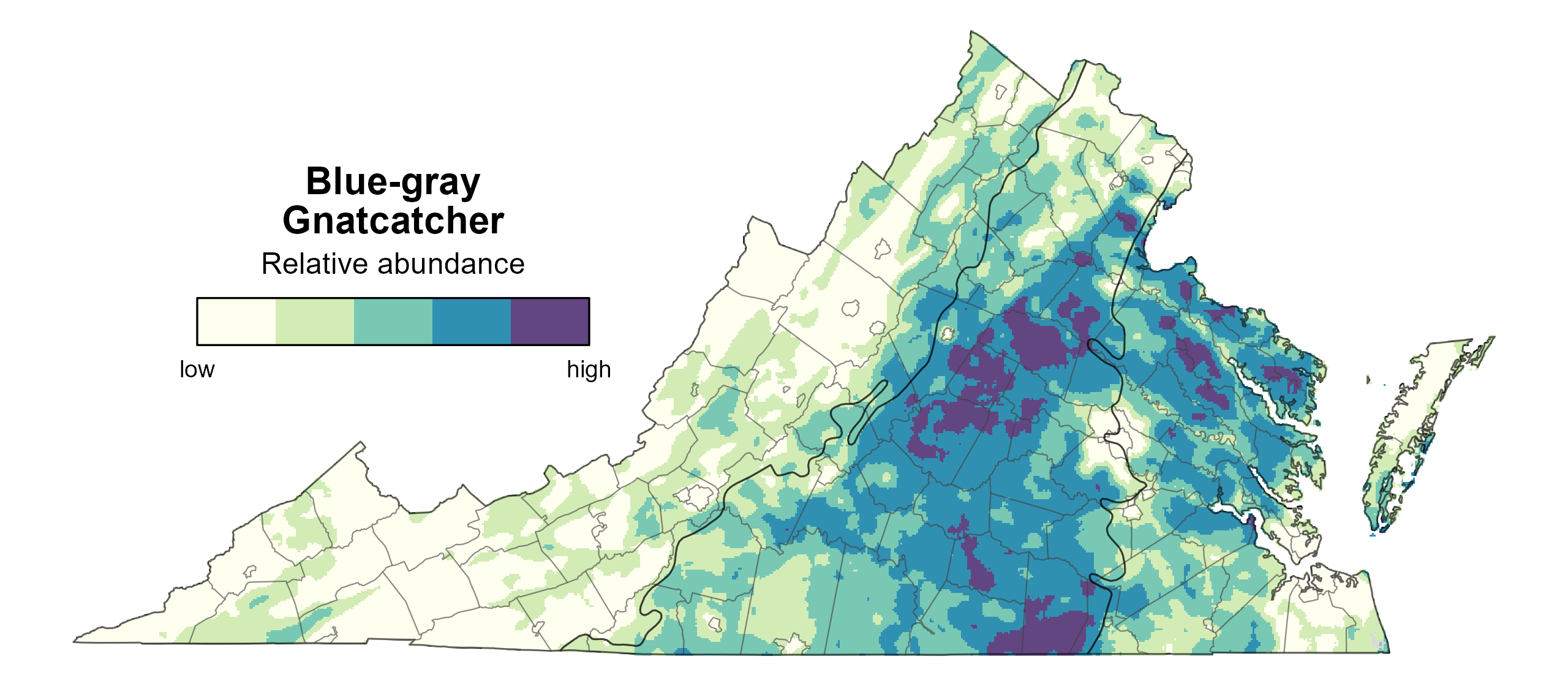

Blue-gray Gnatcatcher relative abundance was estimated to be highest in most of the Piedmont region (except for the more urban areas of the northern Piedmont) and upper Coastal Plain region (Figure 5). This species occurred at moderate to high abundance levels throughout the rest of the state.

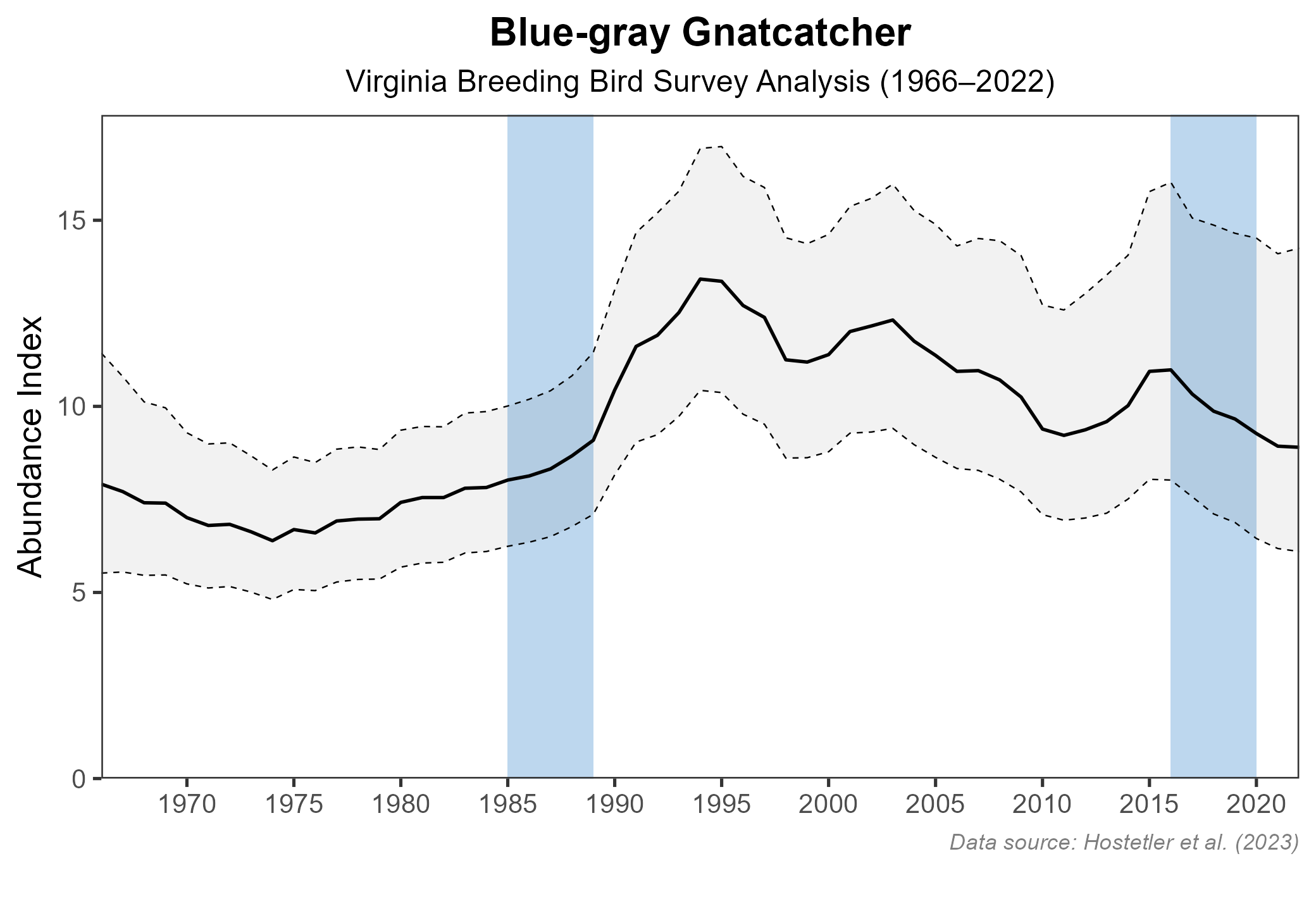

The estimated Blue-gray Gnatcatcher population in the state is approximately 1,418,000 individuals (with a range between 1,124,000 and 1,791,000), making it the tenth most abundant breeding species in the state (among those species for which abundance could be modeled). Population trends for Blue-gray Gnatcatcher appear stable in Virginia as the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) population trend showed a nonsignificant increase of 0.27% per year from 1966–2022 in the state (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 5). Between Atlases, BBS data showed a similar nonsignificant increase of 0.56% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 5: Blue-gray Gnatcatcher relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 6: Blue-gray Gnatcatcher population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Because Blue-gray Gnatcatcher populations appear stable in the state, this species is not the focus of any specific conservation efforts in Virginia. Despite their apparent stability, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher populations can be affected by Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater) parasitism. Gnatcatchers are not strong enough to remove cowbird eggs, so high rates of parasitism can contribute to local declines (Kershner and Ellison 2020). While parasitism has been observed in Virginia, it is unknown how high the rate of its occurrence is in the state.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Kershner, E. L., and W. G. Ellison (2020). Blue-gray Gnatcatcher (Polioptila caerulea), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.buggna.01.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.