Introduction

The Blue Jay is a familiar sight in any woodland in Virginia. Renowned for their beautiful plumage and great intelligence, these birds are easily spotted or heard by seasoned birdwatchers and casual observers alike due to their conspicuous behaviors. They are often encountered in a boisterous mob, attacking predators or mimicking their calls. Their noisy nature belies their cunning and stealth ways, as they will stalk other species to raid their nests and eat their eggs and young. Blue Jays are also great consumers of acorns. One study in Blacksburg, Virginia, found that Blue Jays cached more than 50% of all acorns produced by a stand of pin oak (Quercus palustris) and ate another 20% (Darley-Hill and Johnson 1981). Their caching behavior makes them important dispersers of oak, beech, and formerly the American chestnut (Castanea dentata) (Smith et al. 2020).

Breeding Distribution

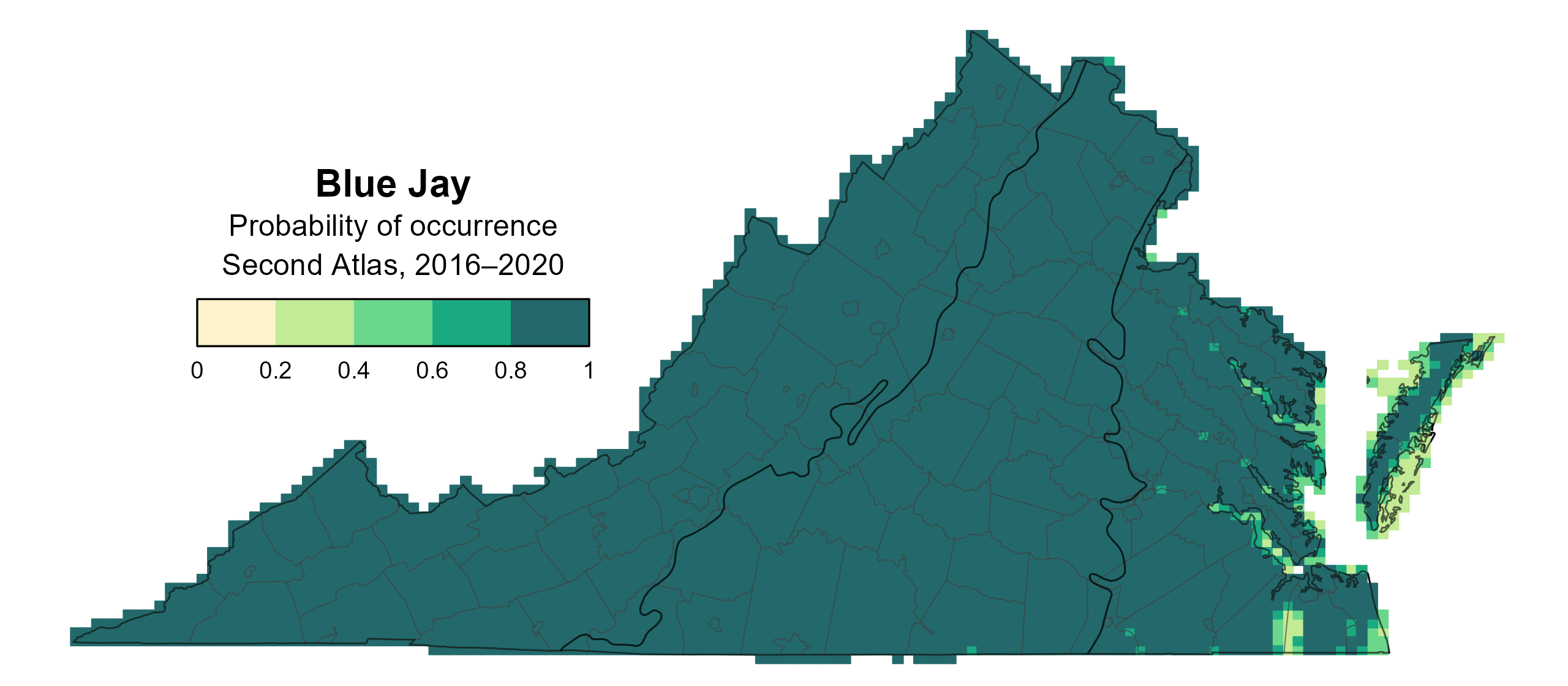

Blue Jays are present year-round in all regions of the state (Figure 1), though they are less likely to be found in blocks bordering open waters of the Coastal Plain, including the Chesapeake Bay and its major tributaries, as well as the barrier islands of the Eastern Shore. Blue Jays are slightly more likely to occur as forest cover increases, but no environmental variables had strong relationships with Blue Jay occurrence because the species has high occupancy across most of the state.

Blue Jay distribution during the First Atlas and its change between the two Atlases could not be modeled due to model limitations (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on where they occurred in the state during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Blue Jay breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Breeding Evidence

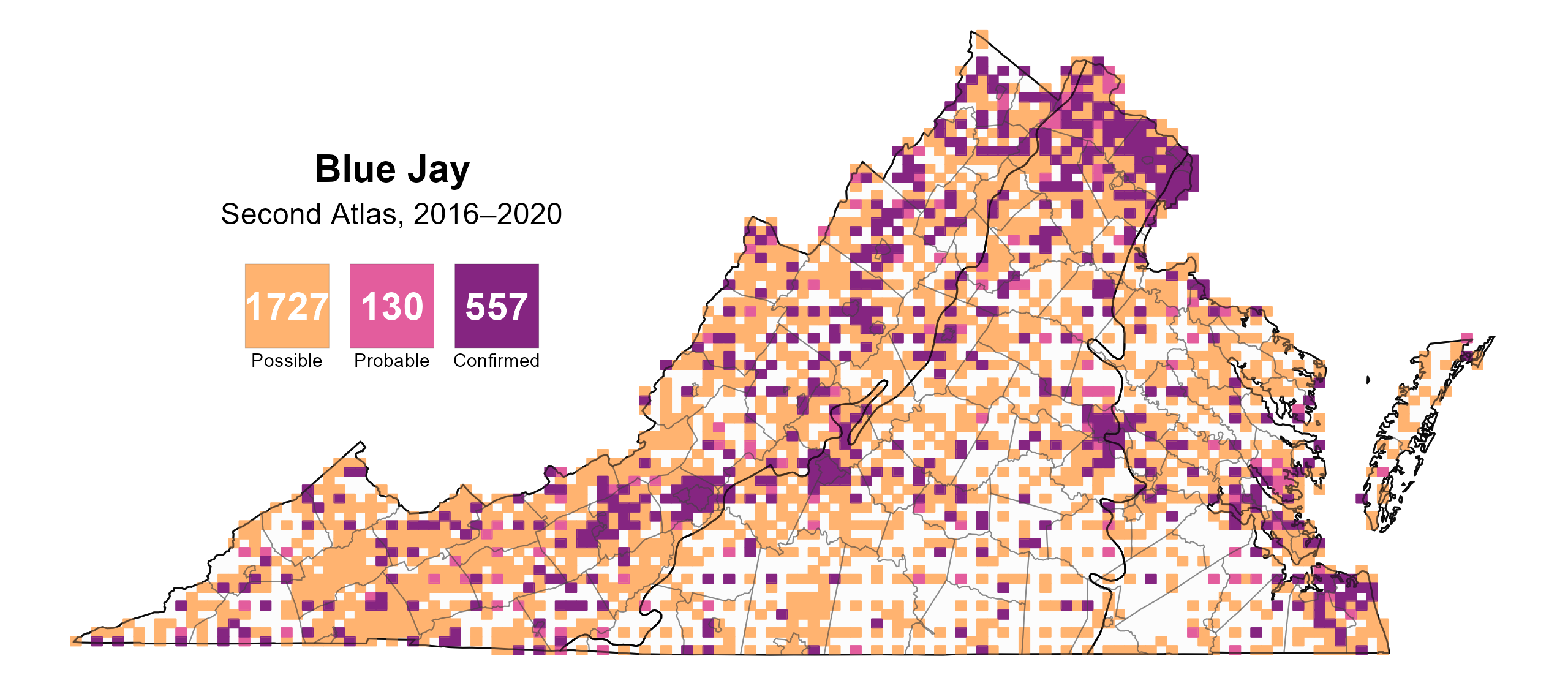

Blue Jays were confirmed breeders in 557 blocks and 120 counties and probable breeders in two additional counties (Figure 2). Confirmed and probable breeders were observed throughout the state during the First Atlas as well (Figure 3).

Nest construction was observed as early as March 25, and breeding was confirmed from April 5 (occupied nest) through September 9 (recently fledged young) (Figure 4). Blue Jays were recorded carrying food as early as March 27, but such early records may represent normal foraging and caching behavior and not breeding activity. Blue Jays can become surprisingly secretive while nesting despite their bold appearance; thus, most confirmations came from observations of fledglings. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Blue Jay, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Blue Jay breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Blue Jay breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Blue Jay phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Blue Jay relative abundance was estimated to be highest in more developed portions of the state, such as Northern Virginia, the greater Richmond region, and the Hampton Roads-Virginia Beach area, as well as in more rural regions of western Virginia such as the northern Shenandoah Valley and the valleys of southwestern Virginia.

The total estimated Blue Jay population in the state is approximately 1,107,000 individuals (with a range between 878,000 and 1,398,000), making it one of the top 20 most populous birds in the state among those species for which abundance could be modeled. Despite their abundance, Blue Jays are declining in Virginia. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) data for Virginia showed a significant decrease of 1.31% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 5). Between Atlas periods, the BBS trend was more moderate but still a significant decrease of 0.85% per year from 1987–2018. The causes of these declines are not known.

Figure 5: Blue Jay relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 6: Blue Jay population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Ubiquitous and abundant in Virginia, the Blue Jay is adaptable to a variety of habitat types and compatible with human development (Smith et al. 2020). Like other members of the crow family, they are susceptible to West Nile virus, which has resulted in the loss of individuals within the Commonwealth but does not appear to have had population-level impacts here (Liu et al. 2011; LaDeau et al. 2007). Long-term annual declines pre-date the emergence of the virus in the U.S. and cannot be linked to any one cause. These declines do not currently appear to be impacting the species’ distribution in Virginia. Continued monitoring of the Blue Jay population will be necessary to determine whether future conservation actions may be necessary.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Darley-Hill, S., and W. C. Johnson (1981). Acorn dispersal by the Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata). Oecologia 50:231–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00348043.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

LaDeau, S., A. Kilpatrick, and P. Marra (2007). West Nile virus emergence and large-scale declines of North American bird populations. Nature 447:710–713. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05829.

Liu, H., Q. Weng, and D. Gaines (2011). Geographic incidence of human West Nile virus in northern Virginia, USA, in relation to incidence in birds and variations in urban environment. Science of the Total Environment 409:4235–4241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.07.012.

Murray, J. J. (1938). The history of a Blue Jay’s nest. The Raven 9:1–2.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Smith, Ki. G., K. A. Tarvin, and G. E. Woolfenden (2020). Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.blujay.01.