Introduction

The American Barn Owl is a ghostly presence, with its harsh call like a scream in the night. True to its name, it haunts agricultural landscapes and open grasslands. In Virginia, they have been found to primarily hunt eastern meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) at night (Rosenburg 1986). During the day, these owls are often found roosting in abandoned silos or barns or in nest boxes, where they are available. They also inhabit coastal marshes rich in small mammalian prey.

In Virginia, these owls are uncommon to rare permanent residents that breed in select locations throughout the Commonwealth (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). American Barn Owls face the same plight of habitat loss and degradation shared by many grassland birds, and with their dwindling numbers, they are at risk of becoming actual ghosts.

Breeding Distribution

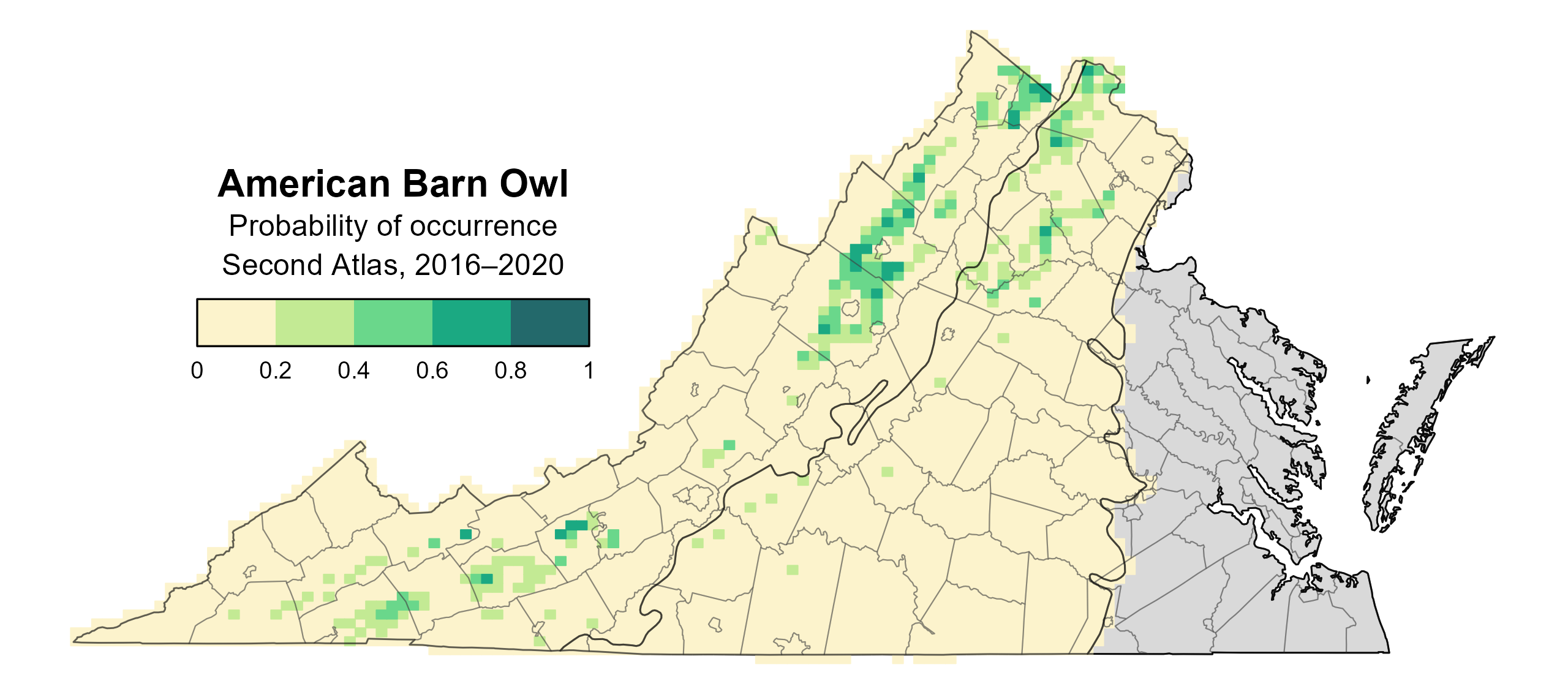

American Barn Owls are found in all regions of the state, but there only existed sufficient breeding data to model their distribution in the Mountains and Valleys and Piedmont regions. The best predictor of American Barn Owl occurrence is the proportion of agricultural land cover in a block. They are most likely to occur in the Shenandoah Valley and in small pockets of southwestern Virginia, including the agricultural valleys of Pulaski, Wythe, Smyth, and Washington Counties, as well as in Burkes Garden in Tazewell County. In the Piedmont region, they are concentrated in central Culpeper, northern Fauquier, and northern Loudoun Counties.

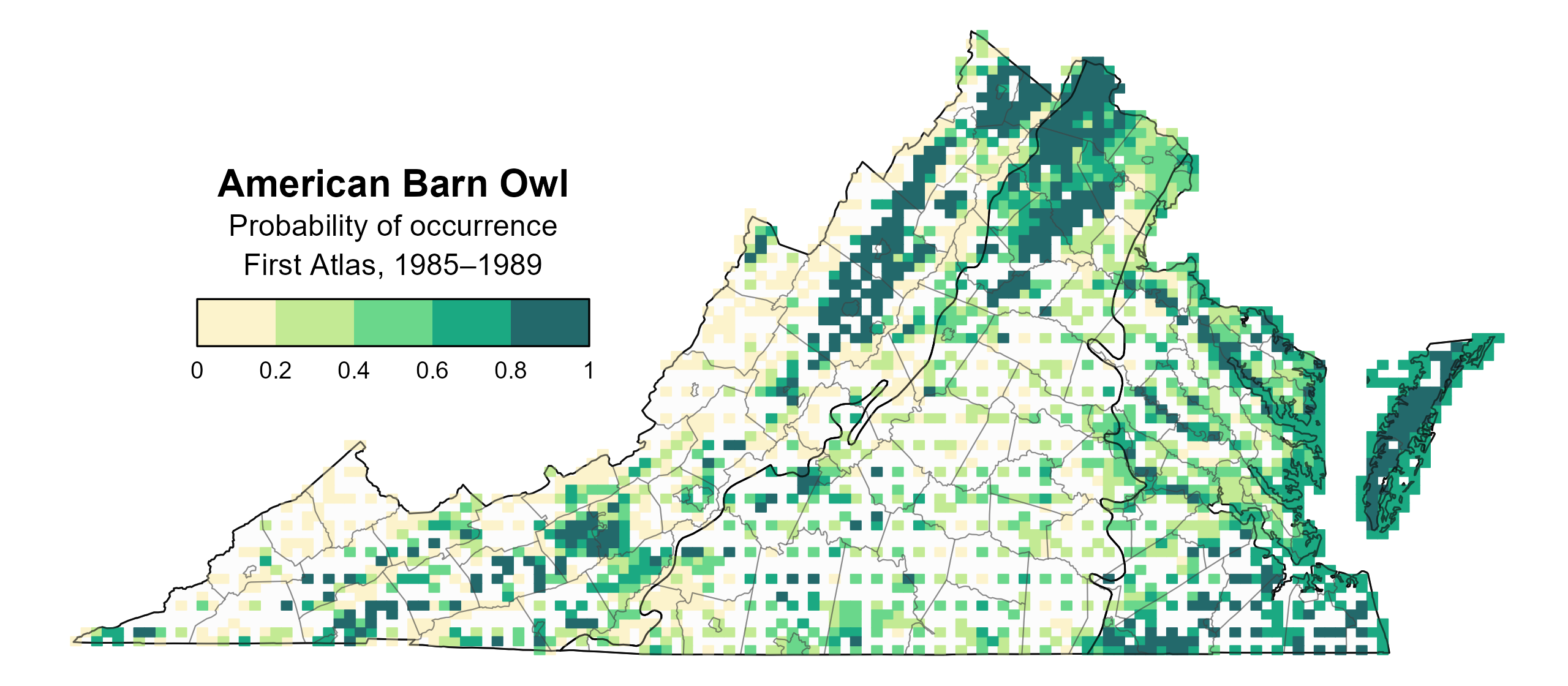

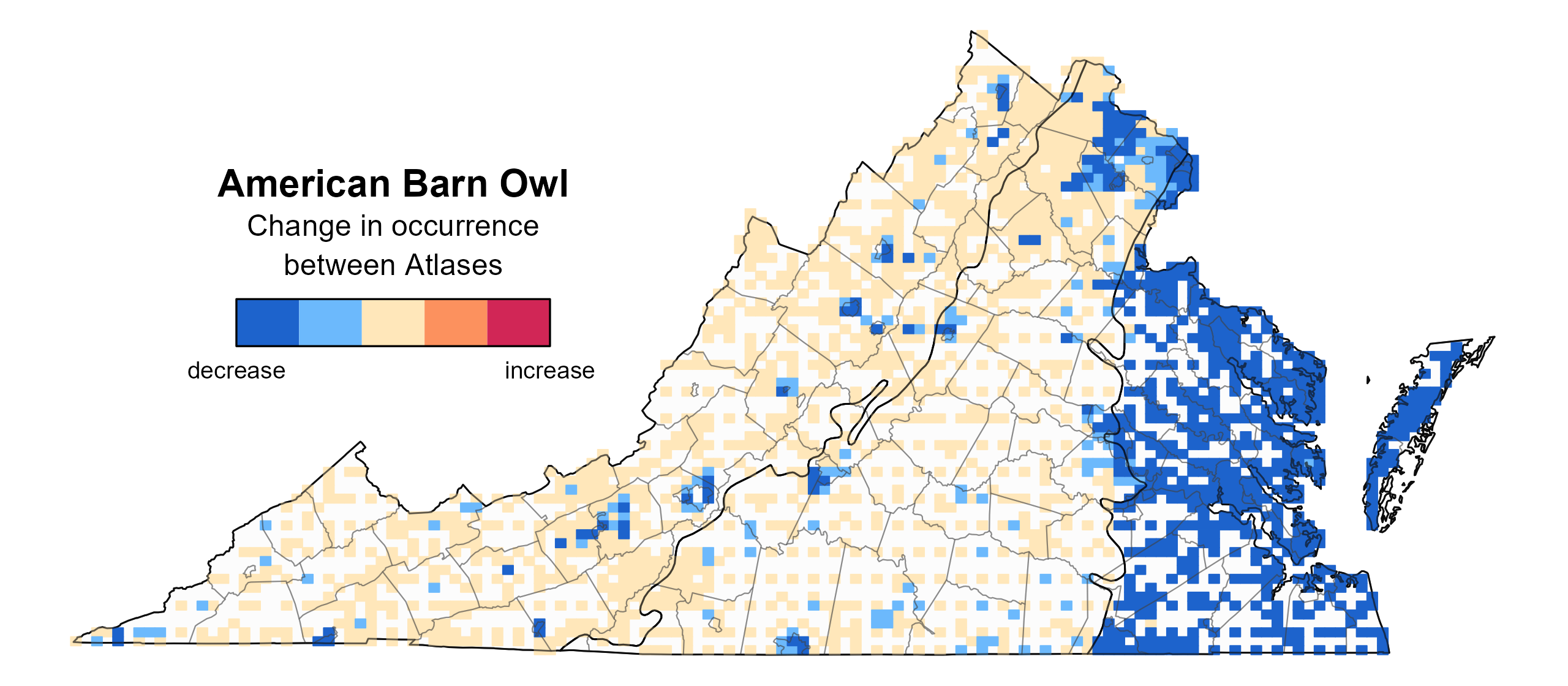

The owl’s likelihood of occurrence generally declined between Atlases across areas of the Piedmont and Mountain and Valleys regions, especially in more developed areas. A comparison between Atlases could not be made for the Coastal Plain, given insufficient data to model the region for the Second Atlas. This lack of data is a function of what is believed to be a dramatic decline in the species as a breeder in that region, based on a large drop in the number of blocks from which it was reported between Atlases (see Breeding Evidence section).

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: American Barn Owl breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray were outside the core range of the species.

Figure 2: American Barn Owl breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: American Barn Owl change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

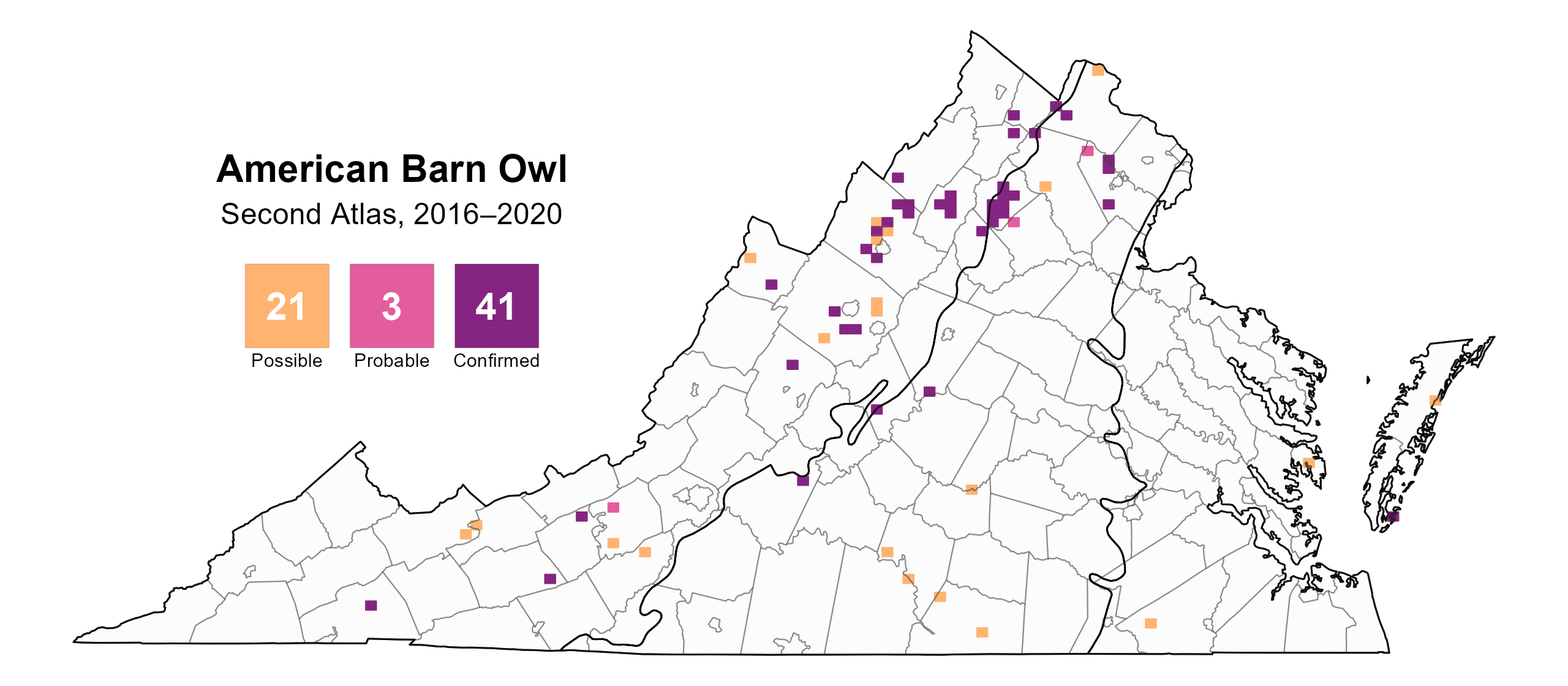

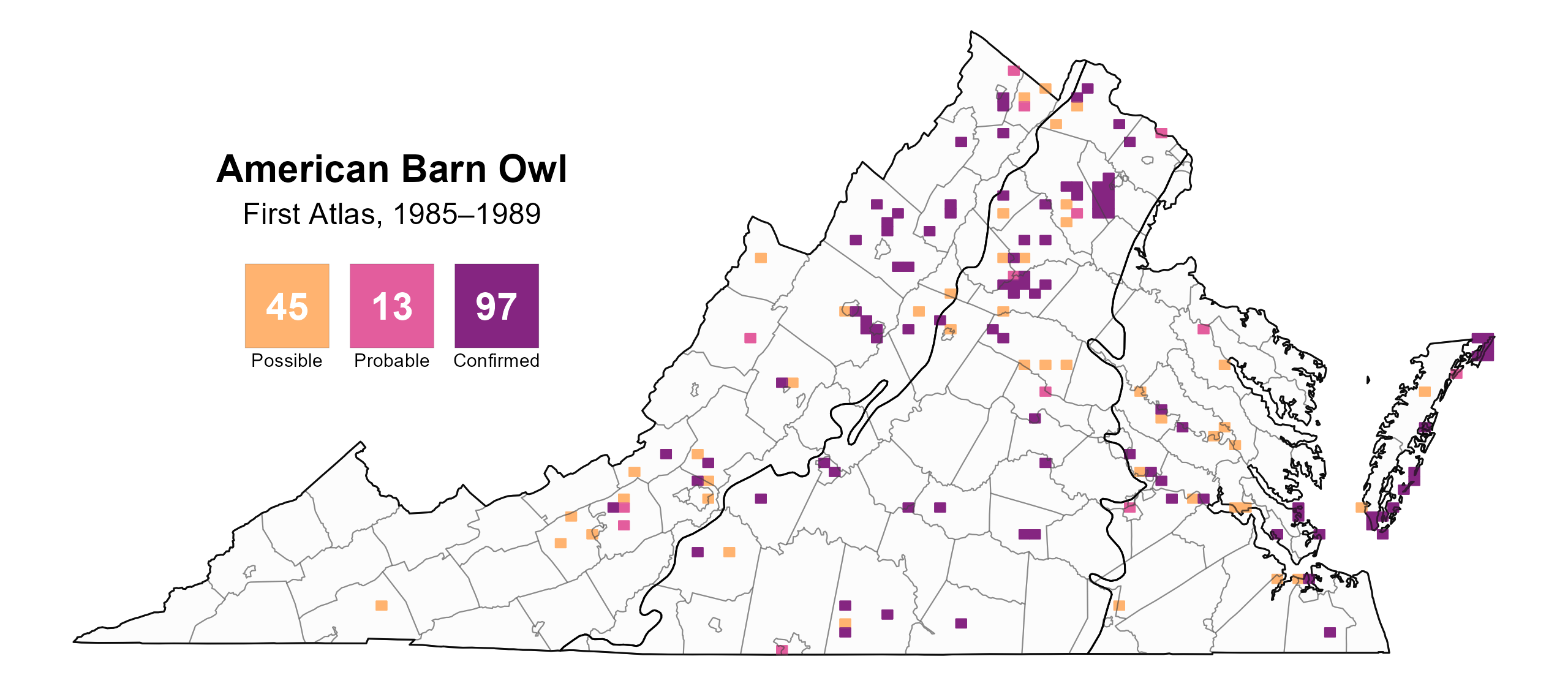

American Barn Owls were confirmed breeders in 41 blocks and 20 counties and were probable breeders in an additional two counties (Figure 4). Because nesting often takes place in structures on private property in rural agricultural settings, nests could not always be confirmed once the presence of individuals at a site was documented. Despite this, the rate of breeding confirmations was relatively high. The number of blocks with breeding observations recorded during the First Atlas was more than double that of the Second Atlas, although there was greater overall survey effort during the latter (Figure 5). The difference between Atlases was especially pronounced for the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions. In the Coastal Plain, American Barn Owls were reported from only four blocks, which indicates a continuing contraction in the distribution and population size within the region.

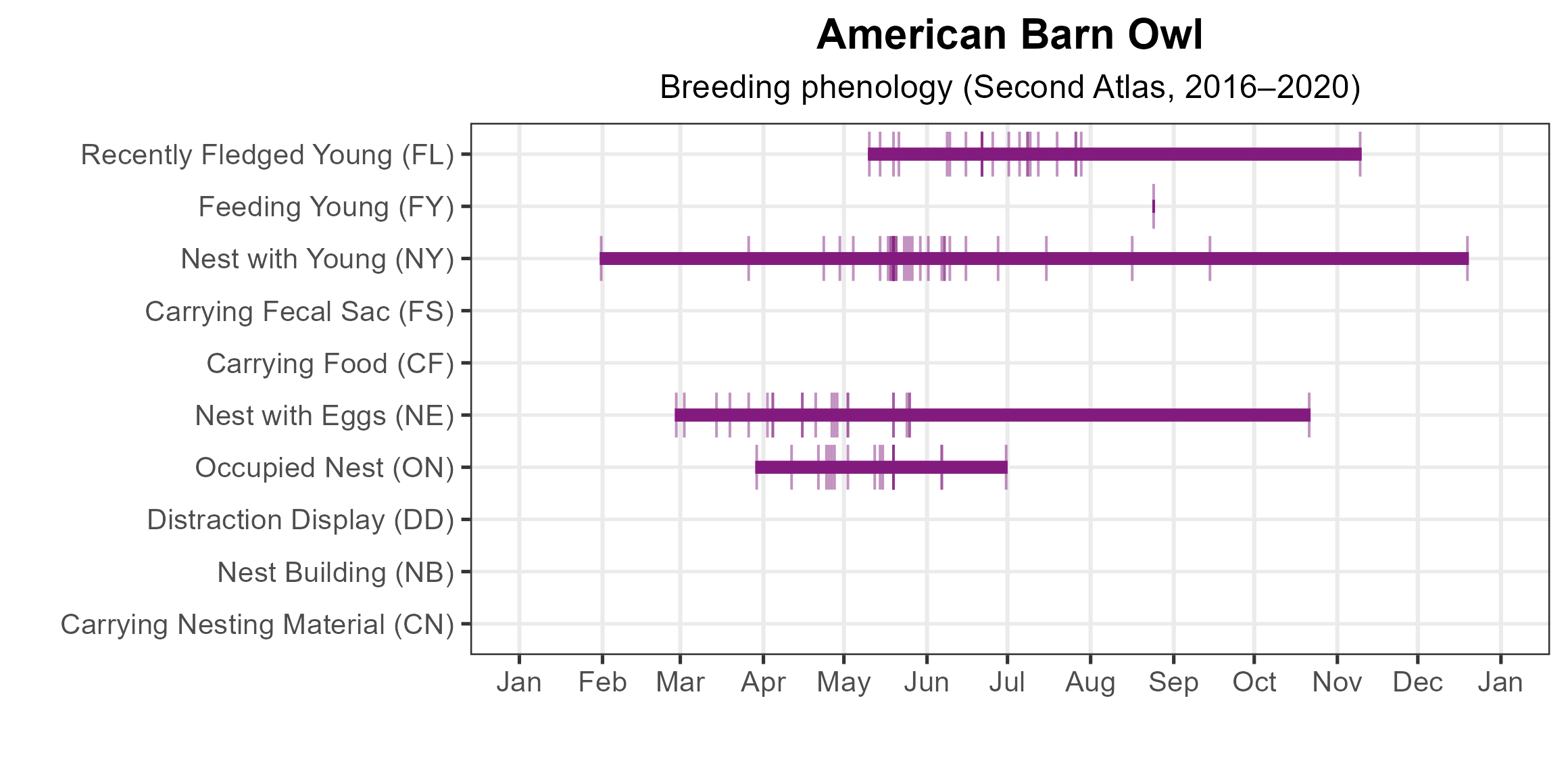

Atlas data indicate that the breeding timeline for American Barn Owls covers nearly the entire year. Eggs were observed from February 28 through a particularly late nest with eggs on October 21 (Figure 6). However, nests with young were observed as early as January 31 and as late as December 19. Most nesting activity was observed in May. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Barn Owl, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: American Barn Owl breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: American Barn Owl breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: American Barn Owl phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

A lack of American Barn Owl detections in the point count data prevented the development of an abundance model, and the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) data does not estimate credible population trends in Virginia or at any geographic scale. It is difficult to assess American Barn Owl population trends without a single reliable long-term data source that covers the entire state.

Barn Owls have declined considerably in the Coastal Plain region. Abandoned duck blinds once hosted nests along major rivers in the region, but these sites go unused today, with only a few breeders left on the outer coastal bays (Bryan Watts, personal communication). Despite the presence of population strongholds, particularly at higher elevations around the Shenandoah Valley, the statewide trend is likely negative (Bryan Watts, personal communication).

Conservation

Population size and trends for American Barn Owl are difficult to determine due to its secretive nesting behavior, nocturnal nature, and lack of response to playback (Morrow and Morrow 2020). However, based on what are believed to be a declining population trend and a small population in the Commonwealth, the species is classified as a Tier I (Critical Conservation Need) Species of Greatest Conservation Need in the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan (VDWR 2025). Given the challenges in documenting Barn Owls, there is a need for targeted surveys to better understand their true distribution, numbers, and population trends in the Commonwealth.

An important threat to Barn Owls is the lack of suitable nesting and hunting sites. Tree cavities, particularly those in large, old trees, are likely less abundant today than in the past. Additionally, the loss of old barns and silos for nesting and their replacement by newer structures that are less accessible to owls have contributed to their decline. The change in landscape composition from pasture and hayfields to more industrial agriculture, heavy grazing, and development of urban and suburban areas has also reduced their habitat.

Addressing the conservation of this species via nest box deployment and monitoring has shown great promise (Marti et al. 2024). A nest box program was initiated by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) across the three ecoregions in the mid-1980s. Monitoring of those boxes, however, has not been consistent, with a systematic effort taking place in the late 1990s (Watts 2003) and a subset of the boxes in the Piedmont being monitored by VDWR in the early 2000s. More recent efforts by other entities include management and monitoring of boxes in the Shenandoah Valley Raptor Study Area (Morrow and Morrow 2020) and box deployment through the Virginia Grassland Birds Initiative. As these efforts have primarily taken place in the Northern Shenandoah Valley and Northern Piedmont, they could be expanded to enhance the conservation of this species. Landowners can contribute to conservation efforts by installing and maintaining these nest boxes on their properties and by preserving old barns and silos that can serve as nesting sites.

Additionally, conducting small mammal predator control would help protect eggs and young owls (Causey et al. 2020; Morrow and Morrow 2020). Finally, ensuring the availability of hunting grounds, such as maintaining open fields and pastures, will also be essential for the American Barn Owl’s survival. Creating and maintaining fallow pastures through the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program, promoting agricultural land easements, and engaging in local land use planning efforts to mitigate development impacts can all play a role in maintaining an adequate supply of the habitat upon which the species depends (VDWR 2025).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Causey, M., L. Morrow, and J. Morrow (2020). Barn Owl nest box productivity in Prince William and Fauquier Counties, Virginia, 1986-2009. The Raven 91:15–19.

Morrow, L., and J. Morrow (2020). Registration and management recommendations for Barn Owl (Tyto alba) roost and nest sites in Virginia’s Northern Shenandoah Valley. The Raven 91: 20–28.

Rosenberg, C. P. (1986). Barn Owl habitat and prey use in agricultural eastern Virginia. Master’s thesis, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist, 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Watts, B. D. (2019). Barn Owl blues. Center for Conservation Biology. (Accessed 21 February 2025).